Ralph Kiner and Branch Rickey: Not a Happy Marriage

This article was written by John J. Burbridge Jr.

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

Branch Rickey assumed the duties of executive vice president and general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates on November 3, 1950. Given Rickey’s accomplishments, there was significant hope that the Pirates would become a force in the National League. Rickey brought to Pittsburgh his philosophy of winning, which was that it couldn’t be done unless you built up the minor-league assets of the franchise. Rickey also was partial to athletic players who could run fast and were good fielders. Rickey also felt it more desirable to trade a proven player one year too early than one year too late.

Branch Rickey assumed the duties of executive vice president and general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates on November 3, 1950. Given Rickey’s accomplishments, there was significant hope that the Pirates would become a force in the National League. Rickey brought to Pittsburgh his philosophy of winning, which was that it couldn’t be done unless you built up the minor-league assets of the franchise. Rickey also was partial to athletic players who could run fast and were good fielders. Rickey also felt it more desirable to trade a proven player one year too early than one year too late.

The Pirates had one proven star: home run-hitting Ralph Kiner. Given that Kiner was slow afoot and had starred for the Pirates between 1946 and 1950, many in Pittsburgh believed that Rickey would trade him quickly. Kiner did stay with the Pirates during 1951 and ’52, leading the league in home runs both seasons, as he had in the previous five. However, hard feelings developed between Rickey and Kiner, resulting in the slugger being traded to the Chicago Cubs in 1953. This paper explores the relationship between Rickey and Kiner and will conclude with some comments on Rickey’s performance in Pittsburgh, his treatment of Kiner and Kiner’s thoughts on Rickey’s legacy.

KINER IN HIS EARLY YEARS AS A PIRATE

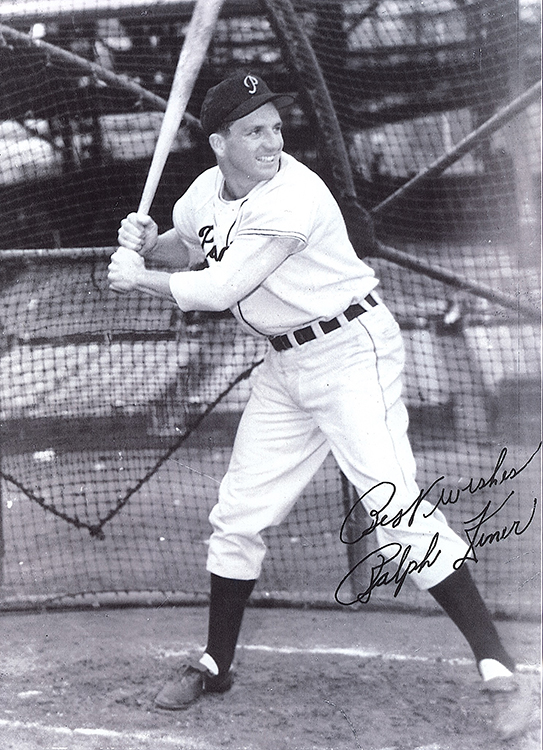

Ralph Kiner joined the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1946. A right-handed hitter, Kiner had a reputation as a slugger in the minor leagues. He fulfilled such promise by leading the NL in home runs every year from his rookie season through 1952. Johnny Mize tied Kiner in 1947 and 1948. In 1947, Kiner teamed up with Hank Greenberg, who had been sold to the Pirates by the Detroit Tigers. To facilitate these two right-handed sluggers, the Pirates reduced Forbes Field’s home run distance to the left field foul pole from 365 to 335 feet and dubbed the area beyond the fence Greenberg Gardens. With their slugging duo, the Pirates saw their home attendance increase by 71 percent from the year before. That was Greenberg’s only year in Pittsburgh, and in 1948 the area was renamed Kiner’s Korner. Attendance increased another 18 percent in 1948 as the Pirates drew more than 1.5 million fans, the most in the National League.

While Kiner was leading the NL in home runs, the Pirates were mediocre on the field, finishing in the second division in the NL in each of the five postwar years before Rickey’s arrival except 1948, when they finished fourth. While 1949 and ’50 attendance did not match the 1.5 million in 1948, attendance in both years exceeded 1 million.

Kiner also became a celebrity off the field. In 1946 singer and movie star Bing Crosby became a minority owner of the Pirates. Crosby introduced Kiner to his Hollywood friends while playing tennis and golf in Palm Springs, California. In 1949, Kiner escorted 17-year-old Elizabeth Taylor to the Hollywood premiere of 12 O’Clock High.1 Kiner settled in Palm Springs and had Hollywood movie stars as his neighbors and fellow golfers. In 1951 he married tennis star Nancy Chaffee.

RICKEY JOINS THE PIRATES

In 1950, Brooklyn Dodgers President Branch Rickey lost a power struggle for leadership of the team. Rickey was aware that Walter O’Malley, another executive with the club, was eager to take control. As a result, Rickey laid the foundation to assume an executive role with the Pirates.

In 1950, Brooklyn Dodgers President Branch Rickey lost a power struggle for leadership of the team. Rickey was aware that Walter O’Malley, another executive with the club, was eager to take control. As a result, Rickey laid the foundation to assume an executive role with the Pirates.

In the history of the game of baseball, Rickey is a legend, having orchestrated front office dealings that resulted in pennants for both the St. Louis Cardinals and the Dodgers. Rickey also created the concept of the farm system, which revolutionized player development. Of course, Rickey is best known for breaking the color barrier with the signing of Jackie Robinson.

On November 3, 1950, Rickey, no longer affiliated with Brooklyn, agreed to a five-year contract for $100,000 per year—about $1 million a year in 2018 dollars—with the Pirates as executive vice president and general manager.2 The contract also called for Rickey to have an advisory role for an additional five years. John Galbreath, principal owner of the club, was mainly responsible for the signing. Interestingly, the other Pirates’ owners, mainly Tom Johnson, were not aware of Galbreath’s dealings with Rickey and his signing.3 Purchasing castoffs such as Preacher Roe and Billy Cox from the Dodgers, Galbreath had developed a relationship with Rickey.

Rickey had high hopes for the Pirates. He started what he termed a five-year plan and also revamped the player development and scouting functions. He was cautious in his comments about Kiner. Many of the scribes covering the Pirates assumed Rickey would deal Kiner since he was slow afoot and not the most adept left fielder. In one of Rickey’s early statements as general manager, he attempted to defuse such views: “We don’t have enough Kiners on the Pittsburgh club, so why would I trade the one I have? We don’t intend on trading Kiner.”4

EARLY SIGNS OF DISSATISFACTION

During spring training in 1951, rumors spread that Kiner was going to be tried at first base. Dan Daniel, the legendary baseball writer for the World Telegram and Sun, inferred this move was initiated by Rickey. Billy Meyer, whom Rickey had kept on as manager, responded, “Kiner handles the glove pretty well, but I am not kidding myself about his ability to adapt himself to the general defensive scheme of a first sacker.”5

The Pirates’ performance in 1951 was disappointing. They finished in seventh place with a 64–90 record, with Kiner’s 42 home runs leading the league. Rickey became aware the Pirates were in significant financial straits because of a decline in attendance and other issues, and called for some moves to lower costs—but no cuts in player salaries. Rickey’s dissatisfaction with Kiner grew when the star went directly to Galbreath with a request for a salary increase. Galbreath and Kiner finally settled for $90,000 for the 1952 season, a raise of $25,000, while most Pirates received no increase.6 This salary made Kiner the highest paid player in the major leagues. This issue further exacerbated Kiner’s less than positive relationship with Rickey.

THE RELATIONSHIP BECOMES CAUSTIC

Seven days after receiving Kiner’s contract for 1952, Rickey went into attack mode. He wrote a 15-page “Personal and Confidential” memo to Galbreath detailing his negative views concerning Kiner. Included in the memo is a ditty he composed contrasting Kiner to Babe Ruth:

Seven days after receiving Kiner’s contract for 1952, Rickey went into attack mode. He wrote a 15-page “Personal and Confidential” memo to Galbreath detailing his negative views concerning Kiner. Included in the memo is a ditty he composed contrasting Kiner to Babe Ruth:

Babe Ruth could run. Our man cannot.

Babe Ruth could throw. Our man cannot.

Babe Ruth could steal a base. Our man cannot.

Babe Ruth is a good fielder. Our man is not.

Ruth could hit with power to all fields. Our man cannot.

Ruth never requested a diminutive field to fit him. Our man does.7

In the last sentence, Rickey was referring to Kiner’s Korner. The memo also criticized Kiner’s love for golf, his sharing an apartment with another person who was known for “promiscuous domestic infidelity,” Kiner’s role as the player representative, and his habit of requesting special privileges that were beyond what should be expected of a ballplayer. Rickey also pointed out that Kiner’s speed and arm strength had deteriorated.8 There is no doubt that Rickey was laying the groundwork necessary to convince Galbreath that Kiner needed to be traded.

1952 was a terrible year for the Pirates and not a great year for Kiner, although he did lead the NL once again in home runs. His batting average was .244 and he did not reach 100 RBIs. The Pirates had a woeful record of 42–112, and attendance plummeted to 686,673 fans. It would seem that Rickey’s situation in Pittsburgh was becoming somewhat precarious, although Galbreath still seemed confident in Rickey’s leadership, and Rickey showed little concern.

1953 SEASON CONTRACT DISPUTE

After receiving Rickey’s memo, Galbreath agreed to have Rickey negotiate Kiner’s salary for the 1953 season. As a result, Kiner knew that the salary negotiations would be much more difficult. With the poor performance of the Pirates and Kiner’s subpar year, it was leaked to the press that the Pirates were thinking about offering Kiner a 25 percent cut from his 1952 salary.9 Rickey’s son, Branch Jr., and Rickey both ventured westward to meet Kiner in California to try to convince him to accept such a pay cut. Kiner responded with the following: “The ball club has always been very good to me, and I’ll go along with a salary cut this year but not 25 percent.”10

Rickey issued the following memorable statement to Kiner during the negotiations: “We finished in last place with you. We can finish in last place without you.”11 Rickey was not hesitant in making the contract negotiations public, and when he did, his comments tended to degrade Kiner as looking for additional money and perks.

The Pirates arranged for spring training in 1953 to be conducted in Havana, Cuba. The spring training schedule called for 24 night games. Several Pirates players were not happy with that many night games and they complained to Kiner, the players’ representative. Kiner took the protest to NL President Warren Giles and Commissioner Ford Frick.12 While no changes were made, such a protest must have irked Rickey.

At a February 13 meeting, presumably about Kiner’s contract, Rickey offered Kiner the inducement to come to spring training on March 15 rather than March 1, the official beginning of camp.13 Kiner agreed. However, the contract with Cuban officials stipulated that Kiner be on hand at the beginning of spring training, so Rickey asked Kiner to show up on March 1 after all.14 Since Kiner had not signed by March 1, he did not show up and became an official holdout.

One report states that Kiner wanted to report later than March 1 because his gift shop in Palm Springs demanded his attention, the beginning of March being the busy season.15 Obviously, such a request would have angered Rickey and other Pirates’ officials. That report also said the Pirates were definitely through with Kiner.16

On March 11, Kiner received a letter from Rickey, but the proposal was not agreeable to him. He sent a wire back to Rickey saying that he would report provided he receives a salary of $76,500, a 15 percent cut. Interestingly, Rickey had made such an offer in their February 13 meeting. Rickey then sent a telegram to Kiner agreeing to $76,500 but saying Kiner had until midnight on March 15 to agree or he’d have to take a 25 percent cut.17 Kiner was quoted by a Pittsburgh newspaper replying, “The only delay in my accepting Pirates terms is salary, and I maintain my legal rights to hold out because of salary difference. Other players have done it, but never has any player had his character questioned or taken the verbal beating I’ve been subjected to.”18 Kiner signed the contract before midnight on the 15th. The holdout was over.

The relationship, not good before, was further damaged by these negotiations. Rickey was now publicly trying to trade Kiner and Kiner was bitter. Years later, Kiner said about Rickey, “He was a hypocrite. He would use any means to sign a ballplayer for as little as he could get him.”19

PIRATES NO MORE

Finally, on June 4, 1953, it was announced that Kiner and three other players had been traded to the Chicago Cubs for six players and cash. Many Pittsburgh fans reacted angrily to the news of the popular slugger’s trade. However, while Kiner performed well in 1953, Rickey was right that Kiner’s future was somewhat bleak given advancing age and back problems. 1953 also saw the Pirates finish in the cellar and lose over 100 games.

During the 1954 season, it became known that Rickey would step down when his five-year contract ended at the end of the 1955 season.20 Rickey’s support had significantly eroded, so his announced departure was not surprising.

KINER SPEAKS HIS MIND

After his baseball career was over, Kiner began what would be a 52-year career as an announcer for the New York Mets. He also had a television show after games called Kiner’s Korner. In 1999, Kiner delivered the keynote address to the New York State Bar Association Labor and Employment Law Section’s Annual Meeting held in Cooperstown, New York, in which he recalled his experiences dealing with Rickey and as the player representative for the National League. He also addressed the 1946 initiative by Robert Murphy to organize the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Pirates voting not to strike during midseason.

Kiner recounted bargaining with Rickey over his 1953 salary and erroneously stated that he ended up signing the $90,000 contract with the 25 percent cut. He then said: “Branch Rickey’s bargaining tactics were actually one of the reasons that led baseball players to unionize in order to gain representation in the contract negotiation process.”21 There is no doubt that Rickey was a hard bargainer, but it was the contract renewal option commonly referred to as the “reserve clause” that gave him the clout he needed.

CONCLUSION

When Branch Rickey joined the Pirates organization, he had some nice words to say about Ralph Kiner. From that point forward, the relationship between the two went downhill. Obviously, Kiner’s role as player representative, his celebrity status, his ability to negotiate salary with John Galbreath, and his lifestyle all contributed to Rickey’s distaste for the home run hitting star. It is somewhat surprising, given Rickey’s stature in the game and his role in breaking the color barrier, that he would resort to the tactics he employed in dealing with Kiner. As Bill James wrote: “Rickey, in one of the oddest moves of his career, (began) systematically destroying Kiner’s reputation as a player, so that he could trade him, it’s nuts.”22 This was not Branch Rickey’s finest hour.

DR. JOHN J. BURBRIDGE JR. is currently Professor Emeritus at Elon University where he was both a dean and professor. He is also an adjunct at York College of Pennsylvania. While at Elon he introduced and taught Baseball and Statistics. He has authored several publications and also presented at SABR Conventions, NINE and the Seymour meetings. He is a lifelong New York Giants baseball fan. The greatest Giants-Dodgers game he attended was a 1-0 Giants’ victory in Jersey City in 1956. Yes, the Dodgers did play in Jersey City in 1956 and 1957. John can be reached at burbridg@elon.edu.

Related links:

- Audio: Click here to listen to John’s SABR 48 presentation on Branch Rickey and Ralph Kiner (MP3; 28:36)

- Slides: Click here to download John’s PowerPoint slides from his SABR 48 presentation (.pptx)

Notes

1 Ralph Kiner with Danny Peary, Baseball Forever (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2004) 164-165.

2 Murray Polner, Branch Rickey: A Biography, (New York: New American Library, 1982), 223; “CPI Inflation Calculator,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=100%2C000.00&year1=195011&year2=201803

3 Andrew O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh (Jefferson, NC: McFarland), 15.

4 O’Toole, 18.

5 Dan Daniel, “Kiner Experiment Not Promising,” New York World-Telegram & Sun, March 20, 1951.

6 Warren Corbett, “Ralph Kiner,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org,bioproj/person/b65aaec9; Ralph Kiner, Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/k/kinerra01.shtml.

7 Polner, Branch Rickey, 230.

8 O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh, 183-191.

9 Lester Biederman, “Pirates Prepare to Trim 25 Per Cent from Kiner’s 90-G Salary,” Pittsburgh Press, December 7, 1952.

10 O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh, 96.

11 O’Toole, 97.

12 Biederman, “The Scoreboard,” Pittsburgh Press, December 31, 1952.

13 Associated Press, “Kiner Standing Pat Despite Rickey Offer,” New York World-Telegram & Sun, March 12, 1953.

14 Associated Press.

15 Joe Williams, “Pirates, Through with Kiner, Face a Cold Market,” New York World-Telegram & Sun, March 10, 1953.

16 Williams.

17 “Kiner, Though Hurt and Baffled, Stands Pat in Feud with Rickey,” New York Times, March 16, 1953.

18 O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh, 98.

19 O’Toole,99.

20 “Rickey to Resign Management of Pirate Club in ’55,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 14, 1954.

21 Ralph Kiner, “The Role of Unions and Arbitration in Professional Baseball,” Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal, Vo1. 17: Iss. 1, Article 8, 3.

22 Corbett, Ralph Kiner.