Rating Baseball Agencies: Who is Delivering the Goods?

This article was written by Barry Krissoff

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

In the summer of 2018 Washington Post reporter Jorge Castillo penned an article about free agent Bryce Harper’s performance and his agent Scott Boras’s interpretation of why Harper was experiencing a subpar year. At the time, Harper was batting a meager .215. Boras pointed out that batting average is not necessarily a good metric, and that Harper was partially a “victim of unusual circumstances,” the increasingly common defensive shift, particularly against left-handed hitters. Boras focused on other positive data, Harper’s impressive hard-hit and walk rates, which were at or near career bests. In the news article, the Post reporter refers to Scott Boras as baseball’s super-agent, as have other authors.1 Writing about eight years ago, researcher Vince Gennaro found that Boras was able to attract the top young baseball talent and was a master of marketing his players, which might be exemplified by the elucidation about Harper.2

In the summer of 2018 Washington Post reporter Jorge Castillo penned an article about free agent Bryce Harper’s performance and his agent Scott Boras’s interpretation of why Harper was experiencing a subpar year. At the time, Harper was batting a meager .215. Boras pointed out that batting average is not necessarily a good metric, and that Harper was partially a “victim of unusual circumstances,” the increasingly common defensive shift, particularly against left-handed hitters. Boras focused on other positive data, Harper’s impressive hard-hit and walk rates, which were at or near career bests. In the news article, the Post reporter refers to Scott Boras as baseball’s super-agent, as have other authors.1 Writing about eight years ago, researcher Vince Gennaro found that Boras was able to attract the top young baseball talent and was a master of marketing his players, which might be exemplified by the elucidation about Harper.2

For sure, Boras has been outspoken on many topics, garnering controversy on issues such as the timing and contract terms of free-agent signings, the level of team salaries in large affluent markets, the timetable of players graduating from minor to major leagues, the number of innings thrown by pitchers coming off injury, and other labor-management issues. From 2015 to 2018, the Boras Corporation has negotiated well over 200 major league baseball contracts, ranging from many one-year deals to Prince Fielder’s nine-year $214 million mega-contract. The total value of all the contracts is nearly $3.5 billion. The Boras Corporation is not the only agency, though, that has substantial economic interests connected to Major League Baseball players. There are at least eight other agencies that have negotiated contracts worth over a billion dollars since 2015 and obviously have an enormous financial interest in player salaries.

The objective of this study is twofold. First, to examine the number and size of contracts that the largest baseball agencies have negotiated for their clients from the 2015 to 2018 seasons. In doing so we distinguish between single and multi-year team control and free agent agreements. The role of the agent in determining contract terms is central in the latter two cases, especially for free agents since the contract duration and salary are negotiated under open-market conditions. Secondly, to appraise the performance of baseball agencies. Our concentration is to gauge the extent to which player representatives have delivered value to their clients. Do some agencies have the ability to secure salary levels that exceed player performance? By the same token, do some agencies appear to sell their clients short by negotiating salary levels that end up understating their future values?

As alluded to above, batting average has limitations as indicative of a player’s performance. With the aid of new technologies and advanced statistics, baseball has expanded and refined the way in which it evaluates player performance. Arguably the advanced metric that has received the most notoriety and exposure is Wins Above Replacement (WAR), which evaluates a player’s overall worth by calculating the number of wins for which he is responsible compared to a replacement-level player at the same ballpark. Fangraphs, Baseball Prospectus, and Baseball-Reference.com publish WAR statistics on their websites for each major league player. Although there is not a standard WAR measure, the use of WAR has become more pervasive and it is now not unusual to see a reference to a player’s WAR in a newspaper article or baseball blog. WAR has been used to estimate the future value of players and no doubt have played a role in the negotiation of player contracts.

Here, we examine players’ salaries and WAR before and after signing a contract for each agency. WAR serves as a measure of on-field performance. Prior to a contract, WAR tells us about past achievements and is an indication of potential success of the player. Subsequent to the contract, WAR indicates the realization of what is accomplished. When dividing salaries by WAR, we convert a player’s WAR into his monetary value.3 Or, as Fangraphs writer Matt Swartz defines, dollars per WAR is the average cost of acquiring one win above replacement on the free-agent market.4 A player whose WAR is 3 and receives a salary of $15 million provides a lower monetary value or higher cost to his team than a player whose WAR is 2 and receives a salary of $6 million.

We will first review the basic tenets and services provided by sports agencies. Secondly, we will discuss the data employed for the analysis. Thirdly, we will compare and analyze contract data and WAR levels for the clientele of a dozen of the largest baseball agencies. Lastly, we will review our findings and take a look at whether the conclusions found in Gennaro regarding Scott Boras as a super-agent continue to hold a decade or so later.

Brief Background on Sports Agencies

There are around 150 sports agencies representing over 2000 current and former baseball players.5 Some of these agencies are very large and not only represent baseball players and other athletes but also artistic entertainers. A leading example is Creative Artists Agency. CAA represents well known movie and TV stars and baseball, football, basketball, hockey, soccer, golf, and tennis players. Independent Sports and Entertainment and The Wasserman Media Group are global corporate entities representing diverse sport figures including snowboarders, Olympic athletes, coaches, and managers in addition to baseball, football, and basketball players. Other agencies specialize in representing baseball players. Athletes Career Enhanced and Secured, the Boras Corporation, and Beverly Hills Sports Council represent hundreds of baseball players at the major and minor league levels in the United States, Latin America, and Asia. Other agencies represent only a few major league clients. Melvin Roman’s MDR Sports Management specializes in Latin American ballplayers and represents current major leaguers Yadier Molina and Jonathan Villar. Turner Gary Sports has former major league clients Shaun Marcum, Brad Lidge, Chad Bradford and current major leaguers Lonnie Chisenhall, and Shane Greene. Of course, with around 150 agencies, other examples abound.

Whether large or small, each of the agencies has specialists who focus on baseball players, usually with a background in sports, business, and/or law. The MLB Players Association (MLBPA) is the exclusive bargaining agent for players negotiating a major league contract and certifies agents. MLBPA regulates and approves General Certified Agents who can represent or advise players when negotiating a contract, Expert Agent Advisors who may assist in the negotiations, and Limited Certified Agents who can recruit and provide clients maintenance services. MLBPA explains requirements and instructions on how to apply for each type of agent.6 Player-agent representation contracts are signed annually and there are occasional disputes about players opting for signing with new agents.7

Agencies offer a variety of services usually emphasizing professionalism and individual attention in managing, marketing, and negotiating on behalf of the player. Among recent innovations and guidance from MLBPA, agencies are examining players’ social media posts and expunging any offensive or hurtful comments.8 For commission, the agency negotiates the contract, arranges for endorsement deals, and advises the player on financial planning and taxes.9 The multisport agency, Excel Sports, for example, asserts, “From draft day, through arbitration and free agency and into retirement, we are industry leaders not only in contract negotiations, but also in meticulously building some of the most successful athlete brands in the marketplace.”10

MLB Trade Rumors conducted player interviews prior to the 2013 season, asking what attributes players seek in choosing an agent. Not surprisingly, players indicated the importance of interpersonal relationships often developing early in their careers.11 Players look for agents that communicate well and demonstrate an understanding of their individual and family interests and goals. Players require the agents to have the requisite legal and business expertise to represent them in negotiations with general managers and other ballclub executives. They also solicit agencies that have connections with marketing and charitable organizations to establish and enhance their “brand.” Most importantly, the players seek the agencies that will be able to negotiate a contract with the largest payout.

Limited information is available on the precise figures that players compensate their agencies. The available literature suggests that agencies receive a commission of four to five percent of players’ salaries.12 This compares favorably to the National Football League and the National Basketball Association, which limit commissions to three percent of salaries. The commissions exclude fees earned from finding, negotiating, and securing endorsement contracts, where agencies typically earn 10 to 20 percent.13

Sourcing and Explaining the Data

Our main data source is Baseball Prospectus’s Cots Contracts, 2015 through 2018. At the beginning of each season Cots indicates the players on every team, contract terms, and the player’s agency (or agent). Contracts in effect for 2015 include single and multiyear agreements that began as early as 2008. For example, Miguel Cabrera’s eight-year, $152 million contract. Multiyear contracts extend far into the future as well, such as Giancarlo Stanton’s 13-year, $325 million contract from 2015 to 2027, plus an option year. Cots lists the player’s agency each year and we matched those agencies with the start of each contract. For example, Elvis Andrus signed an eight-year, $120 million contract negotiated by the Boras Corporation that began in the 2015 season. In another example, early in his career, Gio Gonzalez agreed to a five-year, $42 million contract plus two years of options running from 2012 to 2016 with Athletes Career Enhanced and Secured as his agency. In 2015, Gonzalez switched agencies to the Boras Corporation. Subsequently, his 2017 and 2018 options were exercised raising the contract to seven years for $66 million. Since Athletes Career Enhanced and Secured negotiated the contract, we list them as the agency of record for the $66 million. Similarly, Creative Artists Agency represented Ryan Braun in his five-year, $105 million extension that started in 2016, although it was negotiated a few years earlier. Where data are available we attribute the player with the negotiating agency and adjust salary when options are exercised (through 2018).14

Our main data source is Baseball Prospectus’s Cots Contracts, 2015 through 2018. At the beginning of each season Cots indicates the players on every team, contract terms, and the player’s agency (or agent). Contracts in effect for 2015 include single and multiyear agreements that began as early as 2008. For example, Miguel Cabrera’s eight-year, $152 million contract. Multiyear contracts extend far into the future as well, such as Giancarlo Stanton’s 13-year, $325 million contract from 2015 to 2027, plus an option year. Cots lists the player’s agency each year and we matched those agencies with the start of each contract. For example, Elvis Andrus signed an eight-year, $120 million contract negotiated by the Boras Corporation that began in the 2015 season. In another example, early in his career, Gio Gonzalez agreed to a five-year, $42 million contract plus two years of options running from 2012 to 2016 with Athletes Career Enhanced and Secured as his agency. In 2015, Gonzalez switched agencies to the Boras Corporation. Subsequently, his 2017 and 2018 options were exercised raising the contract to seven years for $66 million. Since Athletes Career Enhanced and Secured negotiated the contract, we list them as the agency of record for the $66 million. Similarly, Creative Artists Agency represented Ryan Braun in his five-year, $105 million extension that started in 2016, although it was negotiated a few years earlier. Where data are available we attribute the player with the negotiating agency and adjust salary when options are exercised (through 2018).14

We source our WAR data from Fangraphs for the years 2005 through 2018. When a contract is negotiated the player, the agency, and the team base the salary and contract length on anticipated future performance. Negotiators often look at past performance to predict what might happen in the future. Rather than using a single year’s WAR, an average of three years prior to the contract is used to represent a player’s achievements and expected performance. For example, in a contract negotiated in 2010, we used average WAR from 2007-2009. For post contracts, we use the average WAR for up to the length of the contract. A 2015 five-year contract would be an average WAR for 2015 to 2019. However, 2019 is not available so in this case we only used four years. To the extent that a player’s productivity declines in outer years of a contract, we may be overstating their productivity. Furthermore, in some instances, particularly post contract years, the number of observations are limited, and in these cases, we opt to use the one or two years of data that might be available. If no pre- or post-WAR are obtainable, then we drop this observation.

An Overview of Agency Contracts

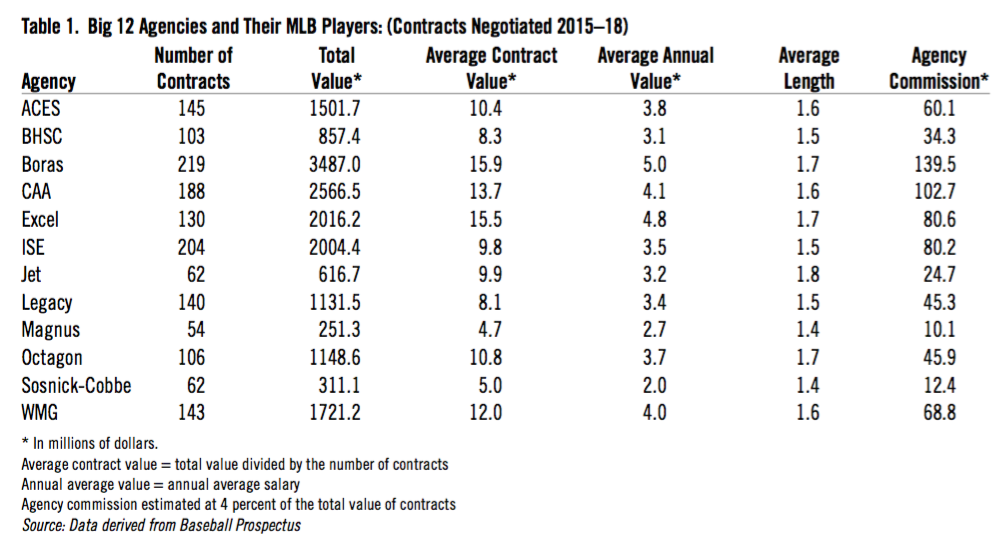

The Boras Corporation is at the head of the class for representing the most MLB players and the size of their contracts. For the 2015 season, the first year of our contract analysis, the Boras Corporation had 75 clients in which they negotiated single or multiple year major league deals starting as early as 2010. Nearly 50 additional agreements were negotiated for each of the next three years for a total of 219 contracts valued at near $3.5 billion or an average contract value of $15.9 million (Table 1). This includes multiple one year or longer contracts for the same player. Boras negotiated three contracts for Carlos Gomez: a 3-year contract in 2014 and single year contracts in 2017 and 2018. For the 2018 season, Boras had 61 MLB clients with single and multiyear contracts originating as early as 2012 (Prince Fielder) and concluding as late as 2025 (Eric Hosmer) and with a total contractual value of $2.1 billion.

Table 1. Big 12 Agencies and Their MLB Players: (Contracts Negotiated 2015–18)

(Click image to enlarge)

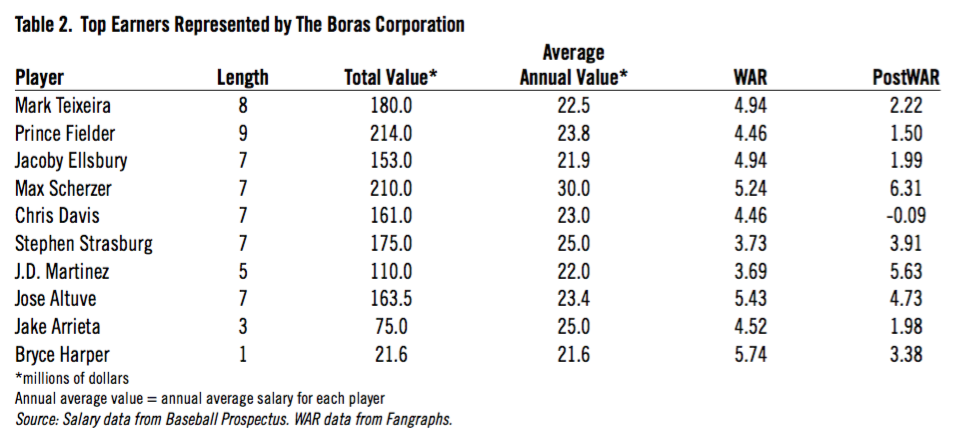

In addition, Boras has the largest average annual value (AAV) of contracts and the largest number of contracts over $20 million per annum (Table 2). To calculate AAV we divide each player’s contract value by the number of years of the contract. We then calculate an average for each agency. Boras’ players have an AAV of $5 million, exceeding all the other agencies in our database. There are 34 major league players with over $20 million annual payouts, 10 of whom are Boras’ clients. The list includes two players who are no longer active, Mark Teixeira (contract expired in 2016) and Fielder (contract expires in 2020), and eight current players. José Altuve, Jake Arrieta, and J.D. Martinez signed contracts in 2018. Of the 10 players, Bryce Harper is the only one in the group who is under team control. Harper has a one-year contract that expired at the end of the 2018 season. Harper’s new contract with the Philadelphia Phillies that started in 2019, unsurprisingly, set a record: 13 years, $330 million, which is more than $25 million annually.

Table 2. Top Earners Represented by The Boras Corporation

(Click image to enlarge)

While the Boras Corporation may be the foremost agency in baseball, it is just one of four sports agencies with over $2 billion MLB player contracts in effect from 2015-2018. And, at least a dozen sports agencies have had contracts over $250 million. In addition to the Boras Corporation (Boras), the agencies are: Athletes’ Careers Enhanced and Secured (ACES), Beverly Hills Sports Council (BHSC), Creative Artists Agency (CAA), Excel Sports Management (Excel), Independent Sports and Entertainment (ISE), Jet Sports Management (Jet), Legacy Sports Agency (Legacy), Magnus Sports (Magnus), Octagon Baseball (Octagon), Sosnick, Cobbe, and Karon (SC), and the Wasserman Media Group (WMG). These agencies do not get as much press coverage as Boras, but along with Boras they account for approximately 40 percent of the total value of all baseball contracts. Furthermore, the dozen agencies account for nearly 75 percent of baseball contracts that exceed $20 million. Table 1 lists each of these agencies with their abbreviated names, the number, contract value, AAV, and the length of the contracts.

The next four largest agencies measured by their total value of contracts are CAA, Excel, ISE, and WSG. CAA has contracts over $2.5 billion, Excel and ISE $2 billion, and WMG $1.7 billion. AAVs are among the highest for these agencies as well, which is not surprising given that they have all but two of the remaining players under contract for our dozen agencies earning over $20 million annually. Interestingly, Zack Greinke (2013 contract) and Yoenis Cespedes (2016 contract) each earned over $20 million and had an opt out which they exercised, Greinke signing a new contract with Arizona starting in 2016 with an AAV of over $34 million and Cespedes re-signing with New York Mets, nearly a year later than his initial contract, for an AAV of $27.5 million.

The average length of contracts is similar across all the agencies around 1.6 years. About 20 percent of contracts are longer than one year. Boras and CAA have the most long-term contracts. They have 24 and 21 contracts four years or longer and four and three contracts eight years or longer, respectively. WMG negotiated the longest contract, Stanton for 13 years, $325 million for 2015-2027, plus the option year. Jet has an average length of 1.8 years for its contracts, a little longer than the other agencies. Jet negotiated several longer-term contracts for players early in their careers, Kyle Seager’s seven-year, $100 million deal and Corey Kluber’s five-year, $38.5 million contract, each with option years, and both signing while they were under team control.

In the last column in Table 1 we examine the estimated commission received by each agency. Using the four percent estimate discussed above, Boras’s commission is nearly $140 million based on the salaries of its negotiated contract players. Fielder’s nine-year, $214 million 2012-2020 contract generates over $8.5 million or a shade under $1 million per year. CAA’s total commission is also over $100 million during this time period with the Robinson Canò 10-year, $240 million 2014-2023 contract standing out with over $9.5 million commission or again a shade under $1 million per year. Isolating the 2018 season and the players’ AAV of the negotiated contracts by Boras and CAA, the earned commissions are nearly $20 and $13 million, respectively.

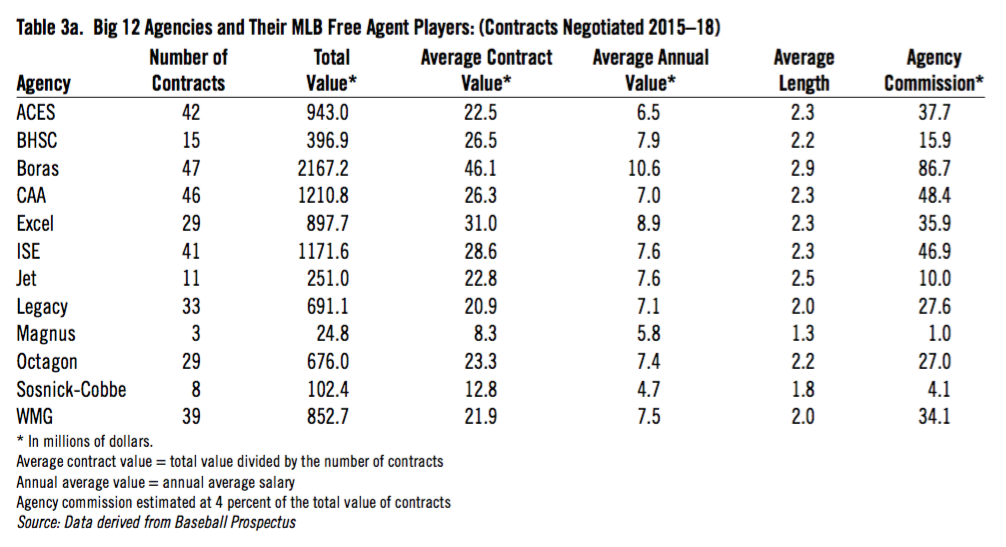

A player’s MLB status—pre-arbitration, arbitration, or free agent—significantly affects the ability to negotiate salary and the length of a contract. The AAV escalates as a player attains more experience and moves into free agency. For our sample of players for the 12 agencies, the average value for team controlled and free agent players increases from $2.5 million to $7.8 million. Clearly, players and their respective agencies have the most negotiating power in the free-agency market and this is reflected in the higher salaries and lengthier contracts. Table 3a shows that Boras has the largest number of free agent contracts (47), the highest total value ($2.2 billion), the highest AAV ($10.6 million), and the lengthiest (2.9 years) contracts.15 Over 60 percent of the value of Boras’s contracts are free agents, adding credence to the often stated comment that Boras’s clients are less likely to sign a long-term contract early in their careers relative to other players. However, there are several notable exceptions mentioned below.

Table 3a. Big 12 Agencies and Their MLB Free Agent Players: (Contracts Negotiated 2015–18)

(Click image to enlarge)

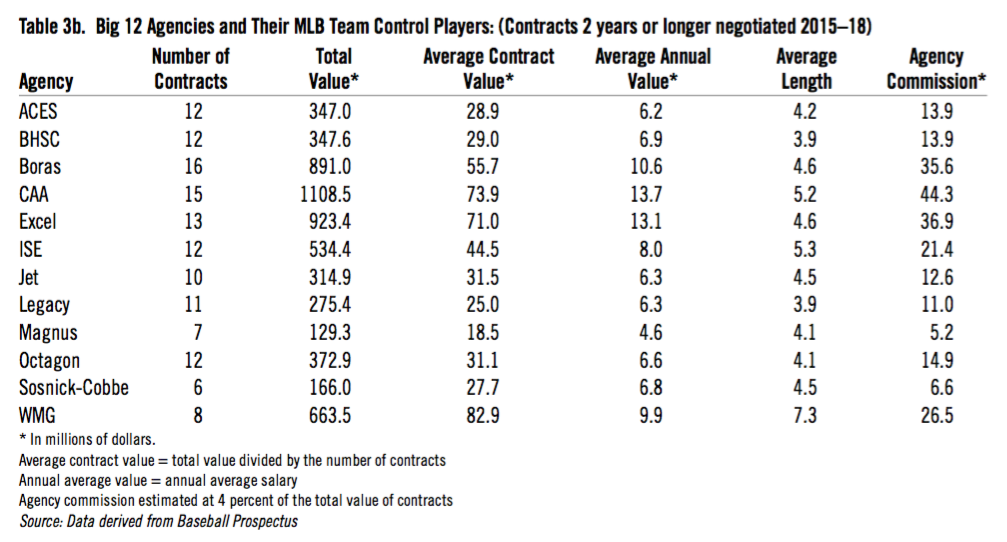

Table 3b. Big 12 Agencies and Their MLB Team Control Players: (Contracts 2 years or longer negotiated 2015–18)

(Click image to enlarge)

Team control players, who are thought to have the most upside by their teams, may coordinate with their agencies to negotiate multiyear contracts or extensions. In these cases, the role for their representatives is considerably more significant than for a one-year deal. Determining the tradeoffs between a guaranteed return of salary for a fixed number of years plus agreeing to any option years provides a player some security compared to one-year or short-term contracts and subsequently becoming a free agent. This is a paramount decision for a young aspiring player. Boras negotiated multiyear million dollar extensions for Andrus’s eight-year, $120 million contract with the Texas Rangers, Stephen Strasburg’s seven-year, $175 million contract with the Washington Nationals, and most recently Altuve’s $163.5 million, seven-year contract with the Houston Astros. Excel negotiated multiyear million dollars extensions for Clayton Kershaw with the Los Angeles Dodgers and Homer Bailey with the Cincinnati Reds, as did CAA for Adam Jones with the Baltimore Orioles as their free agency approached. In other cases, pre-arbitration players agreed to multiyear contracts. Anthony Rendon’s first contract negotiated by Boras with the Washington Nationals was for four years, plus an option year, in his first major league season. ISE negotiated a five-year contract plus an option year with the Arizona Diamondbacks for Paul Goldschmidt prior to the 2013 season, an illustration of an early major-league contract that buys out free agency years. Successful baseball stars in Japan, Korea, and Cuba have inked initial multiyear contracts without any major-league experience. Two prominent examples include Texas agreeing to terms with Japanese star Yu Darvish, represented by WMG, and Oakland coming to terms with Cuban star Yoenis Cespedes through CAA.

Boras, CAA, and Excel have the most team-controlled players with contracts of two years or longer, subsequently referred to as multiyear team control or team control 2 players (Table 3b). CAA has the highest total value ($1.1 billion) and AAV ($13.7 million) contracts, with Buster Posey’s nine-year, $167 million plus option contract with the San Francisco Giants being a notable example. WMG stands out with the longest average length of contracts (7.3 years) but with only a total of eight contracts in this category. WMG clients include New York Yankees superstar Stanton and former Japanese and Cuban players (Darvish, Kenta Maeda, Yasiel Puig, and both Yulieski and Lourdes Gurriel). The combination of free agents plus team control players account for approximately 85 to 90 percent of agency commissions, although only around 30 percent of the total number of contracts.

Differences in Talent and Salaries across Agencies

The information examined in Tables 1, 2, and 3 demonstrate that Boras has the highest paid players on an average annual basis for all free agent players. They also tend to have lengthier contracts compared to the other large agencies. Along with Boras, CAA and Excel have the most multiyear contracts for players under team control and their AAVs for these players are among the highest. There are at least two reasons to explain the success of these agencies: they may be more adept at attracting highly-skilled players, and they may be more skillful at negotiating more lucrative contracts. To distinguish the two reasons, we must examine player achievements before inking their names on contracts.

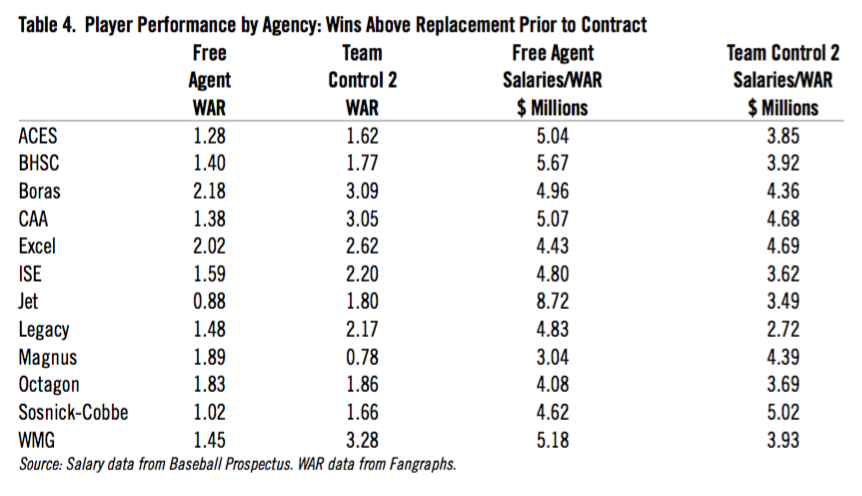

We chose WAR to measure performance, since it is a comprehensive measure. The WAR metrics are shown in Table 4 for free agents and team control 2 players from each of the 12 agencies. We find that Boras players earn higher WAR scores pre-contract than most other agencies for both free agents and team control 2 players, suggesting that its clients may be more talented and successful. Altuve, Harper, and Max Scherzer each have an average WAR of over 5 contributing to the relatively higher average for Boras (see Table 2). The two other agencies that average over 3 WAR for team control 2 players are WMG and CAA. Notable WAR achievements elevating metrics for these two agencies are Stanton’s nearly 5 WAR and Cespedes’s nearly 4 WAR, respectively.

Table 4. Player Performance by Agency: Wins Above Replacement Prior to Contract

(Click image to enlarge)

In the next two columns in Table 4 we focus on the monetary value of players. Players compensated by a higher salary per WAR prior to signing are more costly. No agency stands out, except for Jet, with most agencies having around $5 million per WAR for free agents and nearly $4 million for team control 2 players. There is some variation that can often be explained by one or two contracts per agency, where the player had limited success but still received a relatively high paying contract. For example, Jet has represented catcher Jeff Mathis. While his most recent agreement is relatively small $4 million for two years, his WAR averaged a meager 0.1 prior to signing. Mathis is considered to be an excellent game-caller, helpful to a pitching staff, and is considered “one of the best at something that cannot be measured but is valued.” 16 In this case, WAR may not be an adequate measure of his value to a team.

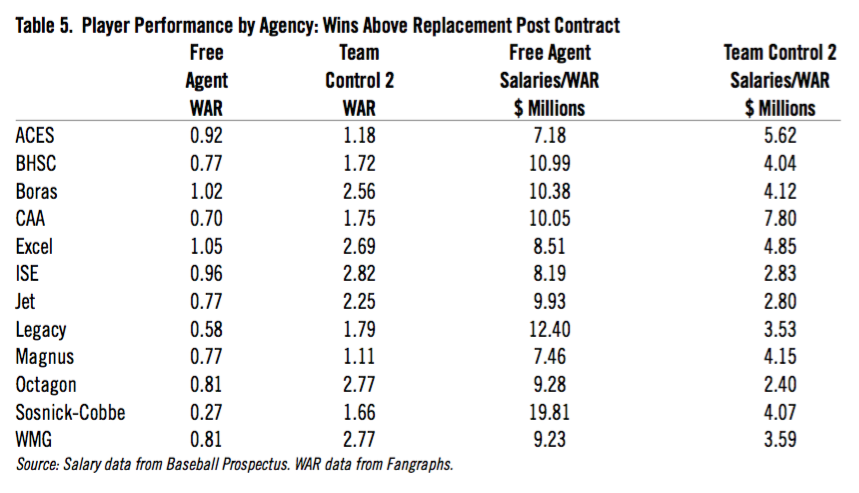

In Table 5 we examine players’ success after signing the contract. WAR outcomes are consistently lower than prior to the contracts. This is an expected result particularly for free agents since these players are older and their performances tend to drop off with age. Because of lower WAR, post-contract salaries per WAR increase considerably for free-agent players. The average dollar cost is approximately $10 million. According to Swartz, the dollar-cost estimate of replacing a free agent is worth around $10 million over the 2015-2017 period.17. Our post-contract results are within the $10 million range for Boras and most of the other agencies. The main outlier, the nearly $20 million per WAR for Sosnick-Cobbe’s free agent clients, reflects a small sample size and some players with slightly negative WARs and high salaries, most notably Jay Bruce’s 2018 three-year, $39 million contract with the New York Mets combined with 2018 WAR at replacement level.

Table 5. Player Performance by Agency: Wins Above Replacement Post Contract

(Click image to enlarge)

Team control 2 players exceed the achievements and are less costly than free agents; this is the case for every agency in Table 5. Coming to terms with team control 2 players for multiyear contracts relative to free agents appear to be advantageous for teams. The team owners absorb the risk of players getting injuries or subpar performances but the team control 2 clients demonstrate greater monetary value than their free agent counterparts. The team control 2 players likely receive less than free agent market rate compensation and tend to be younger.

Concluding Observations: Gennaro Generally Had It Correct

In Gennaro’s 2011 article he concludes that Boras’s hype as super-agent is justified. Our analysis indicates most of the findings related to Boras’s success continues to prevail. We find that Boras has the largest number of major league players under agreement, with an estimated total contract value of $3.5 billion covering contracts signed between 2015 and 2018 seasons. The firm represents clients with the highest average annual salaries and is among the agencies with the longest contracts.

Boras does appear to be a master at attracting the game’s biggest stars. The company retains many of the most successful free agents. Current clients, such as Harper and Scherzer, often achieve higher WAR scores than other players. Toward the end of the 2018 season, emerging Phillies slugger Rhys Hoskins opted to hire Boras as his agent.18 Boras’s reputation as an agent who encourages his players to wait for free agency rather than sign extensions while under team control often holds. However, there are some key exceptions where Boras has negotiated extensions with players’ existing teams at or near market rates. Two relatively recent examples are the seven-year extensions for Altuve and Strasburg.

In addition to Boras we examine several other big agencies in detail. ACES, CAA, Excel, ISE, and WMG each represent major league players with well over one hundred contracts totaling at least $1.5 billion. Each have at least one star with contracts exceeding six years and $100 million. Included in this list are names like Jon Lester, Posey, Greinke, Miguel Cabrera, and Stanton, respectively.

The dozen agencies in our study appear to be competitive with each other when comparing the negotiated salaries given their clients’ level of performance. Whether we are discussing free agents or multiyear contract team control players, the average annual salary per WAR prior to signing contracts are approximately $5 and $4 million, respectively, for each of the dozen agencies. Post salaries per WAR are mostly greater than pre-salary, indicating that performance levels are often less after signing a contract. This is true for free agents in each of the dozen agencies and half of the 12 agencies of the team control 2 players.

Gennaro indicates that Boras is more successful in negotiating maximum value for his clients, achieving nearly twice their average contract values—both salaries and length of contracts—relative to performances. We find a similar result for free agents. Boras’s clients have nearly 90 percent higher average contract values and 45 percent greater WAR. In contrast though, for multiyear team control players, Boras’s clients attain 20 percent higher average contract values but achieve much higher WAR of 45 percent relative to other agencies. Boras may be more successful at negotiating free-agent contracts but this does not appear to be the case for multiyear team control clients.

We should add one more point: our focus has been on a metric that we can measure, namely, salary and WAR. While salaries are obviously a key component a player seeks in choosing an agency, there are likely many personal and branding factors that are important to players in enlisting agency representation. The ability of the agencies to market their players might vary and generate different streams of income.

BARRY KRISSOFF is an Adjunct Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Maryland Global Campus. His first article in the BRJ, “Society and Baseball Face Rising Income Inequality,” was a finalist for the 2014 SABR Analytics Conference Research Awards in the category of Historical Analysis/Commentary. He continues to look forward to a World Series victory in Washington, DC — maybe this is the year! Contact information: bcybermetric@hotmail.com.

Acknowledgements

The author appreciates the careful and extensive critique and suggestions by John Wainio and two anonymous reviewers. We also benefited from correspondence with the Major League Baseball Players Association.

Notes

1Jorge Castillo, “Scott Boras Says Shifts Are Partly Why Bryce Harper Isn’t Enjoying a Typical Harper Season,” Washington Post, July 5, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/nationals-journal/wp/2018/07/05/scott-boras-says-shifts-are-partly-why-bryce-harper-isnt-enjoying-a-typical-harper-season/?noredirect=on

2 Vince Gennaro, “The Scott Boras Factor: Reality or Hype?” Baseball Prospectus, April 15, 2011. https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/13584/baseball-proguestus-the-scott-boras-factor-reality-or-hype

3 Neil Paine, “Bryce Harper Should Have Made $73 Million More.” FiveThiryEight, November 9, 2015. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/bryce-harper-nl-mvp-mlb/

4 Matt Swartz, “Foundations of the Dollars-per-WAR Evaluation Framework.” Fangraphs, March 26, 2014. https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/foundations-of-the-dollars-per-war-evaluation-framework/

5 MLBTR Agency Database. Major League Baseball Trade Rumors. http://www.mlbtraderumors.com/agencydatabase

6 See MLBPA Agent Regulations: http://mlb.mlb.com/pa/info/agent_regulations.jsp

7 Bob Nightengale and Jorge L. Ortiz. “Scott Boras loses in grievance against Beltran,” USA Today, March 26, 2014. http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2014/03/26/scott-boras-grievance-carlos-beltran-robinson-cano-switching-agents/6934915/

8 Jared Diamond, “Baseball Tries to Clean Up After Social-Media Fouls.” Wall Street Journal, August 22, 2018, page A14.

9 Wendy Thurm, “Longtime Agents Slash Fees, Try to Shake Up Industry.” Fangraphs, August 26, 2014. https://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/longtime-agents-slash-fees-try-to-shake-up-industry/

10 Excel Sports Management. http://new.excelsm.com/representation-baseball/

11 See for example: B.J. Rains “Why I Chose My Agent: David Wright.” Major League Baseball Trade Rumors, March 13, 2013, part of a series of interviews of players. http://www.mlbtraderumors.com/2013/03/why-i-chose-my-agency-david-wright.html

12 See Wendy Thurm; Marie Gentile, “The Average Sports Agent’s Commission,” Houston Chronicle, June 28, 2018 (updated), http://work.chron.com/average-sports-agents-commission-21083.html; and Sports Management Worldwide, “Sports Agency’s Salaries,” https://www.sportsmanagementworldwide.com/courses/athlete-management-sports-agent/salaries.

13 Marie Gentile.

14 If options are not exercised then the contract usually includes a relatively small payout to the player. We did not include these payouts so the value of the contracts may be slightly understated.

15 Consistent with MLB rules, the Cots’ database expresses MLB experience in years and days of service. A player becomes eligible for free agency if he has six years of experience at the beginning of a season. However, some players are listed between six and seven years of service who agreed to an extension before they became a free agent (see Altuve, Cots, 2018, for example). We reviewed Baseball Prospectus contract information to discern which players opted for an extension. These players are not included as free agents but are included in Table 2b.

16 R.J. Anderson, “Baseball believes in Jeff Mathis and the hidden value of game-calling by catchers.” CBSsports.com, February 20, 2018. https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/baseball-believes-in-jeff-mathis-and-the-hidden-value-of-game-calling-by-catchers/

17 Matt Swartz, “The Recent History of Free Agency Pricing.” Fangraphs, July 11, 2017. https://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/the-recent-history-of-free-agent-pricing/

18 Steve Adams, “Rhys Hoskins Hires Scott Boras.” MLB Trade Rumors, Setptember 18, 2018. https://www.mlbtraderumors.com/2018/09/rhys-hoskins-hires-scott-boras.html