Remembrance and Iconography of Roberto Clemente in Public Spaces

This article was written by Justin Krueger

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.

Stories about Roberto Clemente are numerous. He is much more than a man who died at age 38 in a plane crash carrying humanitarian aid to Nicaragua. In the half-century since his untimely death, Clemente has transcended to cultural icon and been honored with numerous public remembrances. Public remembrances are value statements. In one part, the act is about not forgetting. It is about saying that a person, place, idea, or event is worthy of public recognition, of public space. That there is value to a wider public rather than to a small group or individual. But remembrance is also about those who enact the remembrance. What is it that the remembrance is supposed to evoke? Or mean? For whom is the remembrance meant?

According to Dr. Chris Stride, a senior lecturer and applied statistician at the University of Sheffield in England who also helps run The Sporting Statues Project, Clemente has more statues worldwide than any athlete other than Pelé.1

Clemente’s remembrance, however, is far more than public statues and memorials. His name, face, and figure has often been utilized in public spaces of high volume: parks, schools, thoroughfares, bridges, stadiums, even postage stamps. In all these avenues, despite diverging depictions or different focal points, Clemente is remembered as an inspiration.

PUERTO RICO

One of the first public spaces in remembrance of Roberto Clemente was dedicated shortly after his death. A newly minted indoor events arena in San Juan, Puerto Rico, was named Roberto Clemente Coliseum (Coliseo Roberto Clemente). It opened in early 1973, barely a month after the ballplayer’s death, and for a time, it was the largest indoor arena in Puerto Rico.2

Clemente’s hometown of Carolina, has several spaces of public remembrance. Vera Clemente, Roberto’s widow, established his dream ‘sports city, the Roberto Clemente Municipal Sports Complex (Ciudad Deportiva Roberto Clemente), between Carolina and San Juan. It currently covers 304 acres and includes numerous athletic fields, and a statue of Roberto Clemente. However, a direct hit by Hurricane Maria, a category five hurricane, in 2017 left extensive damage to the facilities. In 2020, FEMA pledged millions of dollars to help rebuild the complex.

Also located in Carolina is Roberto Clemente Stadium (Estadio Roberto Clemente). It opened in 2000 and serves as the home of Gigantes de Carolina of the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League. Outside the home plate entrance to the stadium is a statue of Clemente in stride, getting his 3,000th hit. Another statue, located outside the stadium at the center-field gate, shows him tipping his cap after reaching that milestone.

A nearby road is named in his honor, and multiple Clemente statues greet visitors to a roundabout fountain near downtown Carolina.

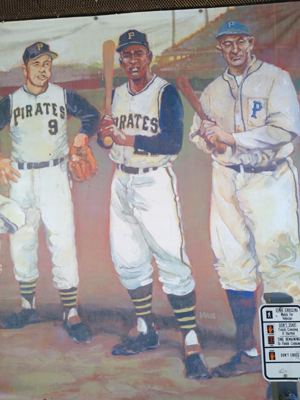

A portion of the Legends of Pittsburgh wall mural by Michael Malle, featuring images of Bill Mazeroski, Clemente, and Honus Wagner. (Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

PITTSBURGH

Clemente in public remembrance is nowhere more evident than in Pittsburgh.

In 1976, Pittsburgh renamed a road that ran along the old Forbes Field in the Oakland neighborhood, Clemente Road. It was renamed Roberto & Vera Clemente Drive in 2021 by City Council approval. The change in name occurred after the Clementes’ sons petitioned the city of Pittsburgh to add their mother’s name.3

On July 8, 1994, during All-Star Week in Pittsburgh, a 12-foot-tall bronze statue of Clemente was placed at Gate A of Three Rivers Stadium.

At the dedication, Dan Galbreath, read a letter that Clemente had written to him and his father, John W. Galbreath, after the 1971 World Series. The Galbreaths had owned the Pirates from 1946 to 1985. In the letter, Clemente insisted that he would never tarnish his legacy by playing just to cash a paycheck. He wrote: “Whenever you don’t think I can contribute to our team’s success, I will retire. I will never play for any other team, ever.”4

Before Clemente’s death, John W. Galbreath had named one of his racehorses Roberto in honor of the star outfielder. The horse went on to win the prestigious Epsom Derby of Surrey, England, in 1972.

After the Pirates moved to PNC Park in 2001, the statue was moved to its new location outside the center-field gate where it now stands between the ballpark and the Roberto Clemente (6th Street) Bridge.

Other Pirate greats with statues at PNC Park include Hall of Famers Honus Wagner, Willie Stargell, and Bill Mazeroski.

The 6th Street Bridge was renamed in honor of Clemente in August 1998. To many, the renaming was public appeasement for PNC Financial Services gaining naming rights to the new ballpark. Before naming rights to the new ballpark had been announced, there was hope among fans that the stadium would be named in honor of “The Great One.”

Roberto Clemente Bridge stretches across the Allegheny River and is part of the “Three Sisters” built in the 1920s, which also includes the 7th Street (now the Andy Warhol Bridge) and 9th Street (now the Rachel Carson Bridge) bridges.

Beyond daily vehicular use, Clemente Bridge also serves as a pedestrian thoroughfare when the Pirates play at home.

Pittsburgh is also home to the non-profit Clemente Museum. The museum is in Engine House 25 in the Lawrenceville neighborhood and includes a large collection of photos and other memorabilia from his baseball career and humanitarian work. As noted on their website:

“Clemente dedicated his 3000th hit to the Pittsburgh fans and people of Puerto Rico. We are honored to be part of Pittsburgh’s dedication to him. Some will come to remember. Some will come to learn. All will leave inspired.”5

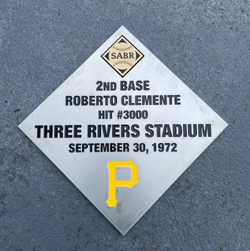

SABR helps commemorate the location of second base, Three Rivers Stadium. (Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

AND THE REST OF THE UNITED STATES

In 2018, four members of Puerto Rican descent in the U.S. House of Representatives sponsored a bill to get Roberto Clemente’s crash site in Loíza, Puerto Rico, added to the National Register of Historic Places. The bill stated:

“Roberto Clemente’s passion and advocacy demonstrated the positive influence that professional athletes could have in improving the lives of others… Roberto Clemente challenged the stereotypes that had marginalized native Spanish speakers in this Nation and remains an icon to many Puerto Ricans and Latinos in the United States and Latin America.”6

A similar resolution was sent by 11 U.S. senators in December 2021 to the Secretary of the Interior.7

In the fall of 2020, the Orange County School Board in Florida voted unanimously to change the name of Stonewall Jackson Middle School to Roberto Clemente Middle School. The student population of the school is predominantly Hispanic. Prior to the renaming, it was the last school in central Florida named for a Confederate general.8 Artist Neysa Millán added a mural of Clemente at the school after being asked by the local Little League.9

Additionally, the Orlando City Council renamed Stonewall Jackson Road in Clemente’s honor in June 2021. Commissioner Tony Ortiz noted that “it was the people who aimed for change.” The newly renamed Roberto Clemente Middle School is located on the road.10

On the occasion, Orlando mayor Buddy Dyer, tweeted:

“Thanks to community efforts, we’re now able to honor Roberto Clemente, a hero to many, and make our city more welcoming with this newly renamed road. Each day… students will get to school via this street that recognizes a humanitarian who uplifted those in need.”11

There are also numerous other public remembrances of Clemente throughout the United States. A section of Route 21 in Newark, New Jersey was designated by the New Jersey Legislature at Roberto Clemente Memorial Highway in summer 2016. The Osceola County Board of County Commissioners in Florida dedicated the Roberto Clemente Memorial Roadway in 2015.

Schools named in Clemente’s honor are located in Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, and Maryland.

Several other parks also are named for Clemente. Roberto Clemente State Park, located in the Bronx, is a 25-acre multipurpose park located alongside the Harlem River. It has playgrounds, basketball courts, numerous ball fields, swimming pool, recreation building, and waterfront promenade. Each year, the park holds a Roberto Clemente Week with special events that celebrate the former ballplayer’s life.12

In 2013, park officials unveiled a life-size bronze statue of its namesake. The statue, commissioned and donated by Goya Foods, shows Clemente raising his helmet in acknowledgement of the crowd after his 3,000th hit.13 The four-foot base upon which the statue stands has the inscription of Clemente’s famous quote:

“Any time you have an opportunity to make a difference in this world and you don’t, then you are wasting your time on Earth.”

It was also the first statue in New York to honor a person of Puerto Rican heritage.

At the dedication of the statue, Clemente’s son, Roberto Jr. noted:

“For the children who use this park, who play here, this is a great way for them to see who the man was…

They will see the statue and be able to learn about Roberto Clemente, not only the baseball player but the human being.”14

Park director Frances Rodriguez commented:

“We are absolutely honored to receive this statue…The significance is great because we are here to serve the community and Clemente was a true humanitarian. He truly cared about other people.”15

In November 2018 the Roberto Clemente Plaza for bus and subway commuters opened in the South Bronx. Like Herald Square in Midtown Manhattan, Clemente Plaza was envisioned as an urban green space and serves about 75,000 visitors daily.16

The monument Para Roberto was unveiled at the plaza in October 2019. Below is a description:

“The entire sculpture is cast in bronze with twelve sugar cane stalks (representing Clemente’s 12 Golden Glove wins) surround a chair made of baseball bats, baseballs, and stickballs with the Puerto Rican flag as the back of the chair.”17

The artist, Melissa Calderón noted:

“The sculpture features an empty ‘Abuelo’ chair- the type a grandfather might use in Puerto Rico, reminiscing and telling stories filled with history and wisdom which represents Clemente in his retirement, had he lived. I’m grateful for the City’s support of this commission and thrilled to see it installed in the heart of the South Bronx where it can become a part of the neighborhood fabric and inspire future generations with Clemente’s example.”18

Another well-known public space named after Clemente is located at Back Bay Fens in Boston. Roberto Clemente Field is part of Boston’s Emerald Necklace, a 1,100-acre chain of parks that was originally designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in the late 1800s. While the field is city property, it is managed by the athletic department of Division III Emmanuel College and used for Saints softball, women and men’s soccer, lacrosse, and track and field.19

A Little League in Branch Brook Park in Newark, New Jersey, is named in Clemente’s honor. A cast of the Clemente statue that is located outside PNC Park was unveiled at Branch Brook in 2012. Young ballplayers play games at Roberto Clemente Field.

A neighborhood park near downtown Miami, Florida, and a city park in Cleveland, Ohio, also are named in Clemente’s honor.

The Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory unveiled its statue of Clemente, crouched in a batting stance, during the summer of 2021. The statue is the sixth at the museum and follows Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Ken Griffey Jr., Derek Jeter, and Jackie Robinson.

Bailey Mazik, the museum’s curator and exhibits director, noted at the ceremony unveiling the statue:

“Clemente had so much talent on and off the field, and what a tremendous understatement that is…He connected people through service and sport. He did what needed to be done for his team and his community.”20

The National Baseball Hall of Fame unveiled bronze statues of Roberto Clemente, Jackie Robinson, and Lou Gehrig at an exhibit in 2008 called Character and Courage. Also, in 2015, a bronze bust of Clemente was unveiled in Boston’s South End at the corner of West Dedham and Washington Street.21

Clemente has also been honored with U.S. Postal Service stamps issued in 1984 and 2000.

Clemente’s number is displayed on the RF porch of Parque Luis Alfonso Velasquez Flores in Managua, Nicaragua. (Courtesy of Steven A. Melnick, Ph.D.)

CONCLUSION

Roberto Clemente was a great ballplayer. In his death, he has transcended the limitations he once lamented during the 1971 World Series:

“I feel that I would be considered to be a much better athlete if I were not a black Latin…I play as good as anybody. Maybe I play as good as anybody who plays the game. But I am not loved. I don’t need to be loved. I just wish that it would happen. There are many people like me who would like that to happen. I wish it for them. Do you know what I mean?’22

Clemente is an iconic figure. In life, he demonstrated that through his athleticism, through his humanitarian efforts, and in his efforts and desire for the world to be a more just place. He is remembered. In the 50 years since his death, he has become a symbol of admiration.

JUSTIN KRUEGER is an assistant professor of social studies education at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, and was a 2021 recipient of the Woody Guthrie Fellowship awarded by the BMI Foundation. Recently he came across a letter that baseball coaching great Billy Disch wrote to his great-grandfather in 1908. It made him smile.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, information was gathered from Baseball-Reference.com and Baseball-Alamanac.com.

Notes

1 Hayes Gardner, “A bronze age for college football: Behind the culture that honors sports figures with statues,” Louisville Courier Journal, January 7, 2020.

2 Judy Cantor-Navas, “Remember Baseball Great Roberto Clemente With These Musical Tributes,” Billboard, December 28, 2017. https://www.billboard.com/music/latin/roberto-clemente-death-anniversary-musical-tributes-8085490/

3 “New street sign unveiled for ‘Roberto & Vera Clemente Drive’ in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood,” WTAE, December 2, 2021. https://www.wtae.com/article/roberto-vera-clemente-street-signs-pittsburgh/38415251

4 Rob Biertempfel, “What if…Roberto Clemente had played 3 more seasons with the Pirates?,” Athletic, August 18, 2021. https://theathletic.com/2765112/2021/08/18/what-if-roberto-clemente-had-played-three-more-seasons-with-the-pirates/

5 “The Museum,” The Clemente Museum, https://clementemuseum.com/museum/

6 Jose E. Serrano, H. Res. 792, December 10, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-resolution/792/text

7 S. Res. 481, December 16, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-117sres481is/html/BILLS-117sres481is.htm

8 Andrew Limberg, “School in Florida renamed in honor of Roberto Clemente,” 93.7 The Fan, September 23, 2020. https://www.audacy.com/937thefan/news/pittsburgh-pirates/school-in-florida-renamed-in-honor-of-roberto-clemente

9 Ezzy Castro, “Central Florida artist creates mural for Roberto Clemente Middle School,” ClickOrlando.com, March 26, 2021. https://www.clickorlando.com/news/local/2021/03/26/central-florida-artist-creates-mural-for-roberto-clemente-middle-school/#//

10 Ezzy Castro, “City of Orlando unveils new Roberto Clemente street sign,” ClickOrlando.com, June 23, 2021. https://www.clickorlando.com/news/local/2021/06/23/city-of-orlando-unveils-new-roberto-clemente-street-sign/

11 Alex Galbraith, “Later, loser: Orlando renames road named for Confederate general to honor Roberto Clemente,” Orlando Weekly, June 23, 2021. https://www.orlandoweekly.com/news/later-loser-orlando-renames-road-named-for-confederate-general-to-honor-roberto-clemente-29545752

12 “Roberto Clemente State Park,” New York State Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, https://parks.ny.gov/parks/robertoclemente/details.aspx

13 Denis Slattery, “Baseball legend Roberto Clemente immortalized with statue at his namesake state park,” New York Daily News, June 27, 2013. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/bronx/inside-the-park-homer-roberto-clemente-article-1.1384602

14 Slattery.

15 Slattery.

16 “Roberto Clemente Plaza,” Third Avenue Business Improvement District. https://www.thirdavenuebid.org/roberto-clemente-plaza

17 Ed García Conde, “NYC’s Newest Monument is a Tribute to Puerto Rican Humanitarian and Baseball Legend Roberto Clemente in The Bronx,” Welcome2TheBronx.com, October 4, 2019. https://welcome2thebronx.com/2019/10/04/nycs-newest-monument-is-a-tribute-to-puerto-rican-humanitarian-and-baseball-legend-roberto-clemente-in-the-bronx/

18 García Conde.

19 “Roberto Clemente Field,” Emmanuel College: Centers, Partnerships & Institutes. https://www.emmanuel.edu/discover-emmanuel/centers-partnerships-and-institutes/community-partnerships/roberto-clemente-field.html

20 Hayes Gardner, “With sons present, Roberto Clemente statue unveiled at Louisville Slugger Museum,” Louisville Courier Journal, August 18, 2021. https://www.courier-journal.com/story/sports/mlb/2021/08/18/louisville-slugger-museum-unveils-statue-famous-latino-athlete/5557290001/

21 Amanda Hoover, “Roberto Clemente honored with statue in South End,” Boston.com, November 19, 2015. https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2015/11/19/roberto-clemente-honored-with-statue-in-south-end/

22 Wells Twombly, “Super Hero,” San Francisco Examiner, January 2, 1973.