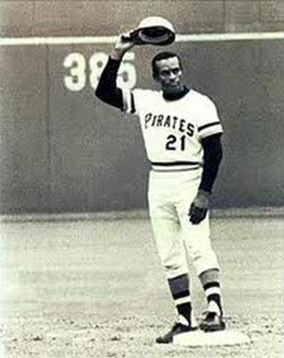

Retiring Clemente’s ’21’: True Recognition for Latinos in the Majors

This article was written by Peter C. Bjarkman

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 27, 2007)

“Most of what I learned about style I learned from Roberto Clemente.” — John Sayles, filmmaker

A ballplayer’s life is rarely if ever finely crafted finish-work carpentry; rather it is almost always rough framing, with all the gaps and gouges exposed to critics and admirers alike. Polishing and puttying and sanding the rough edges while overlooking and/or even hiding the ill-measured angles are the devoted tasks of revisionist historians; eager critics can inevitably expose and exploit the flaws in even the most exemplary heroes. Roberto Clemente, like most of our baseball idols, cobbled together a life on and off the diamond that was as noted for its raw ego and barely con trolled rage as it was justly celebrated for its unrivaled artistry and valor in the face of endless setbacks humiliations that were both real and perceived.

A ballplayer’s life is rarely if ever finely crafted finish-work carpentry; rather it is almost always rough framing, with all the gaps and gouges exposed to critics and admirers alike. Polishing and puttying and sanding the rough edges while overlooking and/or even hiding the ill-measured angles are the devoted tasks of revisionist historians; eager critics can inevitably expose and exploit the flaws in even the most exemplary heroes. Roberto Clemente, like most of our baseball idols, cobbled together a life on and off the diamond that was as noted for its raw ego and barely con trolled rage as it was justly celebrated for its unrivaled artistry and valor in the face of endless setbacks humiliations that were both real and perceived.

If nothing else, Coopertown’s Clemente was an unsurpassed cultural icon in the environs of his Caribbean homeland. Exemplars of this fact are of course legion. Pirates outfielder Jose Guillen, for one, once proudly posed for his colorful 1998 Topps baseball card below a gigantic monument of Roberto Clemente that briefly graced the entrance to now-fallen Three Rivers Stadium. Guillen’s bubblegum card was, to be sure, far more than a clever photo-op for the Dominican-born slugger. It represented a true measure of the way most Latino ballplayers have long felt about their leading idol and the first of their countrymen to reach the hallowed halls of baseball’s Valhalla.

Many Latino stars have quietly honored Roberto with their choice of big league uniform number. Guillen, Ruben Sierra, Sammy Sosa, and Mexican hurler Esteban Loaiza are among the dozens of recent Hispanic ballplayers sporting “21” in tribute to Puerto Rico’s and Latin America’s greatest athletic hero. There is little question that Clemente remains the most significant role model for today’s Latino major leaguers. But are these silent personal tributes sufficient? Should there not be a more formal enshrinement for the immortal Clemente one with some official sanctions from major league baseball itself?

Upon the 50th anniversary of North American baseball’s racial integration, now a full decade in the past, major league moguls appropriately decided to honor Jackie Robinson by permanently retiring the number “42” once proudly worn by the one-time Brooklyn Dodgers star. This precedent-setting honor was certainly not a result of Jackie’s on-the-field resume — which consisted of a mere 10 seasons, barely more than 1,500 hits, and a single National League batting crown. Jackie Robinson’s tribute came because he was a pioneer for many, the sport’s most significant pioneer. Before Robinson, all African Americans and most Afro-Latinos played in their own league buried deep in the shadows of a North American white man’s sport.

That Robinson had actually been preceded in circumventing the “gentlemen’s agreement” by a small handful of largely unnoticed Afro-Latinos (beginning with Cubans Marsans and Almeida in 1911 and peaking with Hi Bithorn and Tomas de la Cruz in the early 1940s) would remain little more than an intriguing footnote. For after Jackie had symbolically if not literally cracked open the door for athletes of color the game not only witnessed a steady influx of black stars, many of them Latinos, but the sport itself was also radically changed forever.

Clemente in the ’50s played much the same role as had Robinson a decade earlier. It was Roberto who paved the way for Latin ballplayers in the big time, especially black Latinos. Cuba’s Minnie Miñoso and Venezuela’s Chico Carrasquel may have preceded Clemente by a handful of summers, but neither wore the stamp of the superstar or carried the image of crusading pioneer. Puerto Rico’s greatest ballplayer not only opened a door to the big league clubhouse, but he was from the first an outspoken and irrepressible champion of his struggling countrymen. Whereas Robinson led silently — letting his bat and glove do all the talking — Roberto led by words as well as by deeds. And sometimes this practice regrettably tarnished his otherwise attractive ball-playing image.

A huge cultural gap dividing Latino ballplayers from many mainstream North American fans during the ’50s and ’60s often worked to Clemente’s distinct disadvantage. Because he was intelligent, intense and always outrageously outspoken, the brash Pirates outfielder was also always a magnet for controversy. Many detractors in the press — as well as among Pittsburgh management and even some teammates — judged him to be aloof, combative, and sullen, often something of a hypochondriac and even a hot dog for his flamboyant playing style. It was the image of hypochondriac that was perhaps Roberto’s most damning and also most unjustified battle scar. Teammate and fellow future Hall of Famer Willie Stargell once lamented that too few properly appreciated the fact that Roberto “played every game like his very life depended on it” and thus suffered more than his expected share of injuries as a result. Roberto himself once complained, “When Mickey Mantle says his leg is hurt no one questions. But if a Latin or a black is sick, they always say it is in his head!”

But cultural perceptions change with time, and a long overdue call has now finally been raised in many quarters across the major league baseball world to retire Clemente’s number as was earlier done for Robinson. Surprisingly the idea has not been universally accepted, and even some Latinos seem to object, as do a number of noted former players of African-American heritage.

Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, for one, has recently questioned where it will all end if Clemente is to be honored in a fashion similar to Robinson. “If Clemente, then who will be next?” Robinson recently commented in an ESPN interview. It would seem that Frank Robinson’s comments are disingenuous at best, since they parrot the same twisted logic once voiced against racial integration in the first place. In light of Rafael Almeida, Marsans, Bithorn and a handful of other Afro-Latinos it is somewhat of a distortion of history to assume that Jackie Robinson — for all his brave pioneering — broke down baseball’s barriers of prejudice entirely by himself. It is a further distortion of racial justice to now claim that Robinson is diminished as a cultural icon by now sharing the stage with other bold and abused pioneers like Doby, Miñoso, Marsans, Clemente, and even Frank Robinson (the first full-time black big league field manager) himself.

One popular New York-area Latino sports broadcaster has recently taken an even less defensible position by raising the claim that Clemente was not the first Latin American in the big leagues, or perhaps not even the most noteworthy Hispanic big-leaguer of integrated base ball’s first full decade. Roberto’s own countrymen Vic Power and Ruben Gomez preceded him to The Show, as did flamboyant Cuban hurler Dolf Luque and flashy Cuban black outfielder Mifioso. Venezuela’s Carrasquel played in the 1951 All-Star Game, three seasons before Clemente arrived on the scene, and Mexico’s Beto Avila had already captured an American League batting title during Roberto’s first year in Organized Baseball.

Such arguments seem weak and naive at best in light of Clemente’s oversize role in the early days of the sport’s full-scale integration. Other pioneers aside, none among the dozens of Latinos cracking the big league barrier be fore Clemente could be called a true diamond superstar. If he was admittedly not the first Latin big-leaguer, Roberto was easily the biggest Latino star of his generation and arguably the biggest-impact Latino ballplayer of the past century.

Robinson, remember, was not technically the first black-skinned big-leaguer either. Branch Rickey’s hand-picked pioneer had been preceded in the first four decades of the 20th century by a handful of dark-skinned Latinos-Luque and Puerto Rico’s Hi Bithorn most prominent among them-all conveniently dismissed at the time by denizens of the press as mere “foreigners” or “Cubans.” Robinson was in reality only the first African American big-leaguer, and then only the first African American of the 20th century. But this conveniently buried fact never diminished Robinson’s remarkable role as racial pioneer. At the time such facts hardly blunted the painful road Robinson had to travel as the “perceived” first modem-era big league black skinned athlete.

Any head-to-head comparison of Robinson and Clemente suggests that the Puerto Rican star’s role as a racial pioneer was every bit as significant. Latinos (Pudge Rodriguez, Tony Perez, Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, Pedro Martinez, David Ortiz) following in Clemente’s footsteps over the past four decades have impacted the game every bit as much as did Robinson-inspired blacks (Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, Don Newcombe, Willie McCovey) in the ’50s and ’60s. Today’s big-league game is dominated by Latin stars who indisputably owe their prominence in large part to Clemente. If not for the politics surrounding Cuba, or still existing MLB restrictions on allowed visas for international ballplayers, today’s Latino domination of the big leagues would be admittedly far greater than it already is. And while many if not most of today’s black stars seem to know little of Robinson’s role back in the ’40s, there are few Latin ballplayers indeed who do not openly acknowledge Clemente as their lasting inspiration.

Acknowledgment of Clemente’s pioneering role comes from all quarters among Latinos. Venezuelan idol Luis Aparicio — Latin America’s third Cooperstown inductee — remembers his own indebtedness by observing that Clemente “was truly a leader for all Latinos. He was always an advocate for our rights,” Aparicio reminds any who will listen to his plaintive testimonials. Recently retired Giants manager Felipe Alou is also an outspoken champion of permanently enshrining Roberto’s memory. Alou recently told an ESPN interviewer (during the 2006 All-Star Game weekend) that he’s heard stories that many of today’s black ballplayers don’t even know who Jackie Robinson was. “I don’t want Latinos to forget who Roberto Clemente was,” Alou justifiably if perhaps unnecessarily cautions.

Acknowledgment of Clemente’s pioneering role comes from all quarters among Latinos. Venezuelan idol Luis Aparicio — Latin America’s third Cooperstown inductee — remembers his own indebtedness by observing that Clemente “was truly a leader for all Latinos. He was always an advocate for our rights,” Aparicio reminds any who will listen to his plaintive testimonials. Recently retired Giants manager Felipe Alou is also an outspoken champion of permanently enshrining Roberto’s memory. Alou recently told an ESPN interviewer (during the 2006 All-Star Game weekend) that he’s heard stories that many of today’s black ballplayers don’t even know who Jackie Robinson was. “I don’t want Latinos to forget who Roberto Clemente was,” Alou justifiably if perhaps unnecessarily cautions.

When it comes to measures of immortality, on-the field, certainly, comparisons favor Clemente over Robinson by the widest of margins. Roberto was a legitimate Hall of Famer by any measure, whereas Robinson seemingly resides in Cooperstown only due to his considerable stature as racial pioneer. A 10-year .311 career batting average, barely 1,500 base hits, less than 150 homers, a single league batting trophy, and a half-dozen All-Star Game appearance hardly seem the key to Cooperstown.

Clemente’s impact on the game goes far beyond his championing of the Latino cause; had the Puerto Rico star been as understated as Felipe Alou or as retiring and press-friendly as Roy Campanella his image would be just as indelible. An even 3,000 hits, 11 All-Star Games, four NL hitting crowns and an unparalleled reputation as a defender bury Robinson’s on-field performances. Clemente may even have been the most exciting baseball player ever to take the field in any league and in any era. The sight of Roberto tearing head-long around the base paths, legging out another extra-base hit, was as thrilling an image as any moment from baseball’s long and dramatic history. Billy Jurges, who played against Ruth and managed Ted Williams, once told this writer that Clemente was easily the best all-around ballplayer he ever laid eyes upon, and the opinion has had numerous seconds down through the decades.

While some fans and historians argue that Clemente was the best natural ballplayer ever, there is almost universal opinion that Pittsburgh’s best-ever outfielder was tops among a new and exciting breed of Latin American athletes entering baseball in record numbers during the two decades immediately following World War II. Clemente performed in a manner approaching pure recklessness, yet also with incomparable grace and unmatched style. Only Robinson ran the bases in similar fashion, and perhaps only Willie Mays roamed the outfield with quite the same flair.

Certainly Roberto’s brilliant achievements lend considerable weight to any such argument for ranking among the game’s greatest. Only 10 batters reached the magical level of 3,000 hits before Clemente got there in 1972, and only 14 more have scaled this lofty peak since “Number 21’s” untimely death over 30 years ago. At the time his marvelous career tragically ended, he was already the all-time Pittsburgh Pirates leader in at-bats, hits, singles, and total bases. He was tied with Honus Wagner in games and second to Wagner in RBIs. This in itself was a most remarkable achievement for a storied franchise that had already boasted such Hall of Fame sluggers down through the years as Wagner, Paul Waner, Arky Vaughan, Ralph Kiner and teammate Willie Stargell.

Clemente won four National League batting titles — including the first ever by a Latino — starred in two World Series, and dominated all pitchers in the 1971 fall classic with a scintillating .414 batting average. He played in 11 All-Star Games (he was selected for a 12th but replaced due to injury), and still holds a record for the most putouts by an outfielder, with six in 1967. He also earned a dozen Gold Gloves (tied with Willie Mays for the most ever by an outfielder) and still is the only player in big league history with more than a dozen fall classic appearances to hit safely in all 14 of his World Series contests. Clemente is also universally acknowledged as the greatest defensive right fielder in the game’s long annals.

No other Latin American before or since has achieved such career numbers or demanded such lasting recognition, though Clemente himself always thought the fame he achieved was all too slow in coming, as it always seemed to be for those of his race and Hispanic background. A perceived insult in the 1960 NL MVP balloting — when he finished only eighth after leading the Pirates to their first World Series in more than three decades — spurred Roberto on to a string of batting crowns that reached four in the next five seasons. But even in the face of such eventual successes the Pirates superstar remained outspoken about the repeated slights leveled at him and his countrymen by an insensitive and unappreciative North American media.

Roberto never minced words about the perceived plight of his countrymen. “The Latin American player doesn’t get the recognition he deserves,” he once told a wire-service reporter. “We have self-satisfaction, yes, but after the season is over nobody cares about us.” Clemente was himself the very prototype if not the poster boy of such repeated under-appreciation. When stardom finally came in the wake of his string of batting titles and a 1966 league MVP, Time magazine was quick to note that still nobody was offering Clemente the chance to do any television shaving cream commercials.

In the end it was these battles for recognition of his fellow Latinos that remain Clemente’s greatest legacy. Roberto always maintained, “My own greatest satisfaction comes from helping to erase the old opinions about Latin Americans and blacks.” There were also his achievements as one of baseball’s most outstanding humanitarians. Roberto died tragically on New Year’s Eve 1972 attempting to transport relief supplies in an overloaded plane to Nicaraguan earthquake victims. He left perhaps his greatest living legacy in the form of his Roberto Clemente Sports City serving disadvantaged youngsters of San Juan and the entire Puerto Rican island. Intimate friend and former Clemente Sports City public relations director Luis Mayoral speaks the final word when he reminds us, “He spoke for Latinos and he was the first among us who dared to speak out.”

There are many blood-pressure-spiking controversies surrounding today’s big league game that seemingly have no easy solutions or bring no unanimity of opinion. Is inter-league play, with its diminishing of traditional rivalries and its destruction of a balanced summer-long pennant race schedule, a boon or a bane for the long term health of the besieged national sport? Should a stronger stance be taken by the game’s moral guardians against players found cheating nature with performance enhancing steroids? Should something be done to protect cherished records against onslaughts by players who have been physically aided by these illegal substances? We can not expect much accord soon on any such contentious issues.

But one debate seems to lead to quick resolution, and one potential action by big league officials seems to be a clear no-brainer. MLB officials today seek to extend a view that baseball is now truly an international game and that the sport’s roots lie just as deeply in the Caribbean and in Latin America as in the byways of North America. MLB’s inaugural World Classic was heavily promoted to underscore and celebrate the game’s Latino and Asian roots. What better way might there have been to open the March 2006 World Baseball Classic — the sport’s first genuine World Series — than with an overdue ceremony permanently retiring number 21 once worn by professional baseball’s greatest Latino and international ambassador? And yet the opportunity went begging. Instead, pro baseball’s top moguls only diminished the game’s Latino heritage by hyping an all-time Latino Legends All-Star team (voted on by media-driven fans saturated by hype surrounding current-era stars) which slighted legitimate Hall of Famers like Tony Perez and Orlando Cepeda and celebrated contemporary favorites like Vladimir Guerrero and Manny Ramirez.

The current 2007 major league season marks six full decades since Robinson’s 1947 debut in Brooklyn and the tumbling of racial barrier for baseball-savvy African Americans. It also marks 40 years since Clemente’s greatest single season (1967) distinguished by a career high .357 batting performance and an eighth straight All-Star selection. The time indeed has now come — some would say it has long since passed — for a proper tribute to Latino baseball’s greatest lasting icon.

PETER C. BJARKMAN is the author of many books including the recent “A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006.” He can be found in cyberspace at www.bjarkman.com and www.bjarkmanlatinobaseball.mlblogs.com. Bjarkman lives in Indiana and travels extensively in Cuba and Croatia.