Review: Brilliant Specialists

This article was written by David B. Hart

This article was published in Fall 2010 Baseball Research Journal

On “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu: John Updike on Ted Williams”

Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu: John Updike on Ted Williams

by John Updike

The Library of America (2010)

$15.00 (hardcover). 64 pages

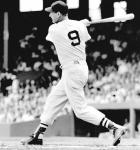

It is hard not to begin this review with the phrase “This slender volume.” (In fact, I avoided doing so only by pulling the coy trick of beginning it the way I just did.) But this is, in fact, a very slender volume, and the few pages it comprises are only sparsely populated by text; it’s more an oversized postcard, really. Other than a very brief author’s preface and a short coda distilled from a few other of his fragmentary jottings on Ted Williams, the book contains only the text of Updike’s celebrated 1960 New Yorker essay (with the footnotes he added in 1965), recounting Ted Williams’s final game (played at Fenway, against the Orioles) and the splendidly improbable home run he hit in his last at-bat. In the case of this volume, however, the minimalist approach has worked beautifully. A compact and handsome fiftieth-anniversary tribute to what many regard as one of the best baseball essays ever written, it is at the same time a pleasant, slightly accidental commemoration of its author, who died only last year.

It is hard not to begin this review with the phrase “This slender volume.” (In fact, I avoided doing so only by pulling the coy trick of beginning it the way I just did.) But this is, in fact, a very slender volume, and the few pages it comprises are only sparsely populated by text; it’s more an oversized postcard, really. Other than a very brief author’s preface and a short coda distilled from a few other of his fragmentary jottings on Ted Williams, the book contains only the text of Updike’s celebrated 1960 New Yorker essay (with the footnotes he added in 1965), recounting Ted Williams’s final game (played at Fenway, against the Orioles) and the splendidly improbable home run he hit in his last at-bat. In the case of this volume, however, the minimalist approach has worked beautifully. A compact and handsome fiftieth-anniversary tribute to what many regard as one of the best baseball essays ever written, it is at the same time a pleasant, slightly accidental commemoration of its author, who died only last year.

Baseball has generated a richer, deeper, and more sustained literary tradition than any other sport. Only cricket has produced books of comparable literary quality, and the best of these—C. L. R. James’s masterpiece of social philosophy Beyond a Boundary, Hugh de Selincourt’s gossamer eclogue The Cricket Match—have been slightly eccentric rarities; there is no large continuous school of cricket writing, and the cricket essay has never become a recognized genre all to itself. The literature of baseball, however, is a crowded and distinguished field, and so it really is a considerable achievement for any single short piece of baseball writing to have acquired the sort of mythic luster that attaches to the Updike essay. It is especially impressive, perhaps, in that it is really the only piece of baseball writing Updike ever did.

Of course, according to Updike he was not really writing about baseball at all but rather about Williams, his boyhood hero. Perhaps this is true; but, even so, some of the more famous passages capture the poetry of the game so exquisitely that they have to stir something in any lover of the game: “Baseball, with its graceful intermittences of action, its immense and tranquil field sparsely settled with poised men in white, its dispassionate mathematics, seems to me best suited to accommodate, and be ornamented by, a loner. It is an essentially lonely game.” And, even when reflecting specifically on Williams, Updike occasionally shows what looks like an aficionado’s eye for detail, as when he calls attention to the qualitatively peculiar trajectory of some of Williams’s low, squarely struck, continuously rising home runs. (My father has often regaled his sons with the golden legend of that trajectory—specifically a home run Williams hit in the old Oriole Park late in his career, a shot that took a foot-long splinter out of one of the wooden seats over the right-field wall, still apparently on the ascent when it did so.)

I suppose the question one ought to ask—since the Library of America has gone to the trouble of producing a single-volume edition of what remains, at the end of the day, only a diverting “occasional” essay—is whether the piece really holds up well fifty years along. In a way—but only in a very impressive way— it does not. The truth is that it’s been set apart in a class of its own for so long that it no longer needs to be measured against other specimens of baseball writing to ensure its reputation; one measures it now against itself, and against the memory of it that one has from previous readings. Picking it up again this time around, I couldn’t help but notice that it has a somewhat slighter feel about it than I remembered it having. I thought I recalled it as being just a bit longer, more lyrical, more suspenseful in its build-up to that final plate appearance, more saturated with the light and colors of late September. But that in itself is a kind of tribute to the essay: It clearly has an evocative power, and generates a kind of emotional atmosphere, that lingers on and that far exceeds what’s immediately evident on the page.

In the end, it really is the nonpareil baseball essay it’s reputed to be. Nothing about it seems dated. (Well, almost nothing: It is momentarily arresting to come across a merely anonymous mention of “the Orioles third baseman”—and, really, by late 1960 most serious followers of the game were well aware of who that was.) Only a few sentences seem overly mannered; for the most part, Updike had already, at only twentyeight years of age, achieved the sparkling ease of his mature style. And all the famous, oft-repeated phrases still ring out with a crystal tone: “the tissue-thin difference between a thing done well and a thing done ill”; or “that intensity of competence that crowds the throat with joy”; or “when a density of expectation hangs in the air and plucks an event out of the future”; or “immortality is nontransferable”; or, of course, “Gods do not answer letters.”

In the end, it really is the nonpareil baseball essay it’s reputed to be. Nothing about it seems dated. (Well, almost nothing: It is momentarily arresting to come across a merely anonymous mention of “the Orioles third baseman”—and, really, by late 1960 most serious followers of the game were well aware of who that was.) Only a few sentences seem overly mannered; for the most part, Updike had already, at only twentyeight years of age, achieved the sparkling ease of his mature style. And all the famous, oft-repeated phrases still ring out with a crystal tone: “the tissue-thin difference between a thing done well and a thing done ill”; or “that intensity of competence that crowds the throat with joy”; or “when a density of expectation hangs in the air and plucks an event out of the future”; or “immortality is nontransferable”; or, of course, “Gods do not answer letters.”

And, perhaps most importantly, the high points do not tower over the rest of the essay. It’s a model of elegant writing throughout. Even the brief précis of Williams’s career with which Updike sets the scene is graceful; only the most interesting and salient statistics are cited, and always in order to cast light on the strangely remote character of the man who amassed them. Then the narrative proper begins, and proceeds at just the right pace; the story almost seems to tell itself. Of course, in a sense it did tell itself. How Updike would have finished the tale if Williams had weakly flied out in the eighth is hard to imagine. He might not have written about the game at all; or he might have dwelled longer on its soft autumnal sadness, and tried to write it with even greater poignancy. Whatever the case, it would have lacked that last, faintly magical moment that draws the whole story—not only the story of that day, but the story of Williams’s entire career—to its achingly symbolic dénouement.

In long retrospect, it seems to me that Updike and Williams were oddly suited to one another, and it’s something of a fortunate accident that their careers briefly converged in one unexpectedly exquisite magazine article. This may seem like a less than gracious observation, but I mean it as very high praise indeed: Soberly and honestly considered, each man was a brilliant specialist—by which I mean, each was supremely skilled in one vital facet of his craft, and merely better than ordinary at all its other aspects. Williams was a pure hitter of almost uncanny ability, of course, with that fluid, oddly dipping and rising yet perfectly timed swing of his: a dead pull hitter in the live-ball era who ripped heroically at everything inside and yet who could still post averages with which Ty Cobb or Rogers Hornsby would have been quite contented come the fall. It almost defies belief, frankly. And yet, at everything else in the game he was unexceptional. On the bases or in the field, he discharged his duties well enough, and he kept himself in good athletic trim throughout his playing days; but it was only with the bat that he stood apart from other players.

Similarly Updike was, at his best, an altogether magnificent prose stylist. There are many, many passages in his collected works that rival or surpass the best work of just about any other English-language writer of the twentieth century; there are whole paragraphs and chapters of almost delirious beauty. And yet he never really wrote a great book. Even the very best of his novels (such as The Centaur) and the most accomplished of his short stories (such as the early Maples stories) always somehow seemed to add up to less than the sum of their glittering sentences and ingenious metaphors. They were good novels and good stories, diverting and clever, and sometimes astonishingly good in many of their individual parts; but they were never masterpieces.

That, though, is not a criticism. The careers of both Williams and Updike serve as excellent reminders that, in most walks of life, only a very few of us are capable of doing anything as near to perfection as humanly possible. For anyone, though, who does have the ability, concentrating on that one extraordinary skill or gift, even at the price of doing everything else (at most) only a little better than average, is the surest way to achieve genuine greatness. And, having achieved it, such a person should certainly be regarded not only with admiration, but also with a little awe.

DAVID B. HART is the author of five books, including “Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies” (Yale, 2009), and of the article “A Perfect Game: The Metaphysical Meaning of Baseball” in First Things (August/September 2010).