Robert ‘Bob’ Addy: And Now You Know the Rest of the Story

This article was written by William Humber

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

Robert “Bob” Addy’s Canadian baseball success story begs a really big question. Why are we only hearing about him now? In the last 10 years, thanks to researcher Peter Morris, Addy’s Canadian roots have been highlighted, but this knowledge has taken its sweet time spreading to all corners of the baseball world.1 Now additional details of the Addy story, of which Peter was uncertain, can be told.

Robert “Bob” Addy’s Canadian baseball success story begs a really big question. Why are we only hearing about him now? In the last 10 years, thanks to researcher Peter Morris, Addy’s Canadian roots have been highlighted, but this knowledge has taken its sweet time spreading to all corners of the baseball world.1 Now additional details of the Addy story, of which Peter was uncertain, can be told.

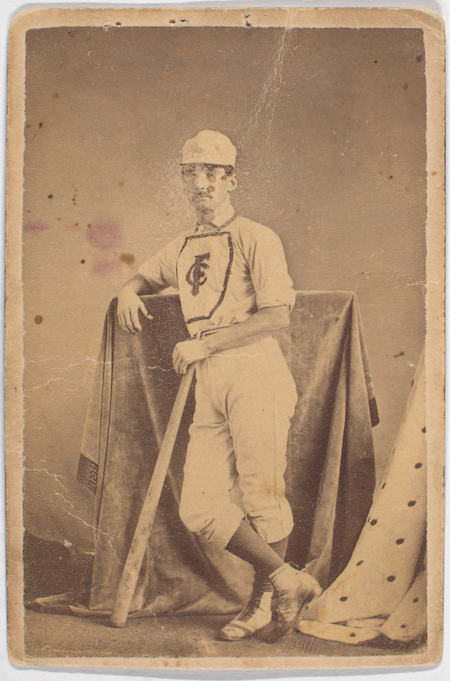

Bob Addy was the first Canadian not only to play, but also to excel, at both the nascent professional game and its major-league startups in the United States.2 He was the first Canadian to both umpire3 and manage,4 if only briefly, at the game’s highest levels. Some accounts say he was the first ballplayer of any origin to slide into a base, but given how the game is filled with such myths, it is more likely he was among the first to popularize the move.5 He even experimented with a version of baseball on ice.6 It was a dismal failure, but not too offbeat for a guy from Canada, where he was born in 1842 in Port Hope, Ontario.7 He not only learned to play baseball there, but his renown as a cricketer as well followed him throughout his later baseball career.8

Bob left Canada around his 20th year to join his older brother George in Rochelle, Illinois, near the Canada Settlement in Ogle County, Illinois, where he most likely hoped to pursue his career as a tinsmith, the training for which he had completed in Port Hope. Fortuitously, Rochelle was near Rockford, Illinois, home of one of the standout baseball teams of the 1860s and early 1870s, the Rockford Forest City.9 Addy joined the team in 1866. It featured two Baseball Hall of Famers, Al Spalding and Cap Anson, though not at the same time, and a number of players with near equal proficiency, including Addy and Ross Barnes. When the Rockford team joined the National Association for its inaugural 1871 season, Addy immediately became the first Canadian to play professionally at the game’s highest level. Bob Addy can therefore be considered Canadian baseball’s “missing link,” filling in the one gap (much of the 1870s) in the otherwise continuous record of Canadians playing the highest-caliber baseball in the United States. He flourished at that level while an increasing number of similarly gifted Canadian players elected to remain at home, their participation in the game in Canada enabling baseball to appeal to all ages, eventually in all parts of the country, and even to gain playing adherents among First Nations, women, and a small but enthralled African-Canadian population.10

To put the game in Canada into its historical context, we know that the ancestral “folk” nature of baseball-type games goes back thousands of years, long before their play in North America. These games were ritualistic, of a looking-back character, childlike in seriousness, and connected to religious custom or an associated culturally ordained celebration.11 In most cases they were introduced from the United States into the Ontario (then known as Upper Canada) portion of the British Empire’s territory of Canada through Loyalist and other settlement beginning in the 1790s.12 Such play, however, came as an English or European custom, not as an American-developed or -owned one. Baseball would co-evolve as a modern sport in Canada alongside its development in the United States in the period roughly between the 1820s through the early 1850s. Despite being unabashed Anglophiles, Canadians opted for baseball over cricket because they had contributed to the former’s evolution, and because it was seen by many as a better bat-and-ball game for participants.

While many additional examples of this process can be cited, of most significance to the career of Bob Addy were two reports from Upper Canada in 1803 demonstrating the manner in which the English and European, by way of the United States, folk game of “base ball” was becoming embedded in the emerging Canada. In 1878 H. Belden & Company’s Historical Atlas carried the following account:

“The first Court of Queen’s Bench that ever assembled in the counties of Northumberland and Durham was held in a barn on the premises of Mr. [Leonard] Soper, in Hope, on which occasion the judge (Major McGregor Rogers), lawyers and other officials, chose sides and played a game of ball, to determine who should pay the expenses of a dinner.”13

Hope is the territorial jurisdiction surrounding Port Hope. The account concluded, however, by noting:

“This statement is made on the authority of a pamphlet issued by Mr. Coleman a few years ago. As will be seen, further on, it is contradicted by the accounts of the ‘Town of Newcastle’ and loss of the ‘Speedy,’ with the judge, crown prosecutor, & c., on their way to hold a court at Presque Isle.”14

The contradiction was not regarding the game of ball, but the identity of the court proceedings on the 1803 premises of Mr. Soper as a Court of Queen’s Bench, when in fact they were a district Court of Quarter Sessions.15 The Belden Atlas description of the 1803 Court proceedings had essentially reprinted John Coleman’s 1875 acc ount.16 Since the Coleman account had been published only three years earlier, long after the 1803 event, its legitimacy could be questioned. So from whom did Coleman get his account? On page 44 of his 1875 booklet, he lists people who helped him in his research. They included Timothy Soper. In 1803 Timothy Soper was the 14-year-old son of Leonard Soper, on whose property the court was held. A reasonable conclusion is that Timothy Soper either witnessed the play of ball firsthand, or learned about it from his father, Leonard. When Coleman published his account in 1875, Timothy Soper was still alive. He lived until 1878 and is buried in the Bowmanville Cemetery.

An additional validation is found in the diary of Ely Playter (1776-1858), a farmer, lumberman, militia officer, member of the Upper Canada House of Assembly, and in 1801-02 a tavern-keeper who lived in and around York (Toronto). Concurrent with the time of his writing, he described coming to town and joining, on Wednesday, April 13, 1803, “… A number of Men jumping & Playing Ball…”17 We do not know definitively, and will never know, what “ball” they were playing, but Playter’s connection to Major McGregor Rogers, who presided over the Hope Township Court Sessions, is captivating. Rogers married two of Playter’s sisters, Sarah and Elizabeth (not at the same time, but after Sarah’s death). Playter and Rogers thus had a close personal relationship. While distance would have ensured they met only occasionally, we can see the real likelihood of their sharing an interest in the game of ball.

It is not surprising that Bob Addy grew up playing cricket, the more advanced of the two bat-and-ball games, but given the above early reference to “ball” in the vicinity of Port Hope, we can reasonably conclude he was also exposed to and played “base ball” type games as a child, and into his teenage years. We have at least five accounts from the Port Hope Guide newspaper of his cricketing prowess.18 His batting was a particularly strong point. But where is the baseball proof? At first glance it appeared to be found in a New York Clipper account (August 25, 1861) for a game that Addy’s hometown Port Hope Mechanics played against the Live Oak of Bowmanville, and for which it was reported, “The pitcher of the Mechanics, Addie, is also a very fine player and a very powerful bat.” Addy’s name was misspelled, but this was not surprising in an era when such was common. There are no other names similar to Addy in the Port Hope Directories of the era.19 There can be little doubt it is him but quibblers will still argue that the proof is tentative. It was confirmed however in the Port Hope Guide20 of November 15, 1873, as found in the publication, Doings of the Week the World Over, describing Bob’s one-time play with the Port Hope Mechanics beginning in 1858. The Guide story recognized the ballplayer’s relation to a local man, his brother James Addy.21 Most of the story, with the exception of his birth year, was correct, but researchers can’t have everything.

Additional information has also come to light regarding Addy’s family life. He appears to have met his wife, Ida, and married her when he was 28 and she was either 14 or 15. It was not a happy union. There was a boy, George, undoubtedly named after Bob’s older brother. In a telling commentary seeking a divorce in 1880, Ida cited multiple cruelties, infidelities, and actual violence against her.22 It later transpired that she probably needed a quick resolution of the matter, having become pregnant by her future husband. She withdrew the charges, the divorce went through, and eventually Ida and her new husband, Jerry Kinney, a railroad conductor, moved to Pocatello, Idaho, just down the street, as it turned out, from where Bob and his second wife settled.23 Ida no doubt wanted to be near her son, whom Bob had taken to Wyoming. For Ida’s part, she and Jerry had many more children and she lived long into the twentieth century, dying in 1938.

As he aged, Bob Addy made a point of disowning his past. The 1880 Wyoming census listed Bob and George with the misspelled last name of Addey, and Bob’s birthplace as New York. Eventually he was more specific, claiming to have been from Rochester, New York, despite ongoing descriptions of him as a Canadian.24 For years, baseball encyclopedias listed Rochester as his hometown, and even his daughter from his second marriage confirmed this heredity to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. The reasons are complex, and possibly will never be known. However, when his Rockford team toured Canada on multiple occasions in the 1870s he tired of fans calling out his name as one of their own. “I care nothing for them,” he is said to have mouthed on one occasion, and in this era of advanced American xenophobia, hiding even this small “national” difference from his teammates seemed appropriate.25

But Bob’s connection to Port Hope was not quite severed. From a distance, he and George oversaw their younger brother’s last will and testament in 1886, and then their mother’s in 1889.26 Both had died in Port Hope. Meanwhile Bob continued to be listed locally as a possible returnee among Port Hope’s network of “Our Wandering Boys,” despite it being unlikely he would ever leave the American West.27 He eventually died in Pocatello in 1910; the house he built there now has heritage acknowledgment.28 Another side of his personality was revealed on jobs such as this. It was said “… boys would climb to roofs which he was tinning under an August sun to listen to his ceaseless chatter, which was more witty and clever than the routine of most professional monologuists.”29

An intriguing element in this family story was his brother George’s youngest daughter, and Bob’s niece, Jane. George had sent Jane’s older sister, Sara, to Port Hope in the late 1880s to marry a much older widower with whom she had six children in rapid succession.30 Jane might have feared a similar fate. She was a talented vocalist and to forestall any repeat, she relocated to England near century’s end, catching on with the D’Oyly Carte Opera company. Meanwhile, at the other end of the world, and with their research vessel, the Belgica, entrapped in the ice of an Antarctic winter, the crewmates passed their days of endless darkness admiring the photos of females in the magazines brought along. Polish scientist Henryk Arctowski fell in love with an image of Jane Addy.31 Eventually the freed boat made its way back to Europe, where Henryk pursued Jane to Paris. They married in London. The two became leading Polish intellectuals between the wars, Jane as a translator into English of Polish works, and Henryk as a respected academic.32 Only because they were attending a conference in Washington in 1939 were they spared the fate of so many Poles when the Nazis invaded their country. They never returned. Following their respective deaths in the 1950s, their cremated remains were collected in the United States and shipped to Warsaw for burial as heroes of the nation.33 Today, Henryk has a scientific base named after him in Antarctica, as well as a bi-annual award, while Jane’s acclaim among Poles historically matches her illustrious uncle Bob’s in the United States … and now in Canada!

WILLIAM HUMBER’s five books on baseball include Diamonds of the North: A Concise History of Baseball in Canada (1995). He has been a facilitator since 1979 of an in-class and now online subject Baseball Spring Training for Fans, is an inductee into Canada’s Baseball Hall of Fame (2018), and was appointed to the Order of Canada (2022) for his baseball research. He finds it all a tad overwhelming.

Notes

1 Despite Peter Morris’s uncovering of Bob Addy’s true identity, many online biographies of William Phillips from New Brunswick continue to list him as the first Canadian big leaguer, while Addy, despite his playing acclaim, had yet to make it into Canada’s Baseball Hall of Fame in St. Marys, Ontario, as late as 2021. Editor’s Note: This oversight was rectified in November of 2021.

2 Addy’s statistical performance spans baseball’s fully emergent time and as such encompasses a formal league (the National), another not always afforded full major-league identity (the National Association), tournaments, one-off encounters (such as with the famed 1869-70 Cincinnati Red Stockings), and games outside the purview of what we now call “Organized Baseball” (in Port Hope and Denver). Many of these games are today described as “exhibition,” but unlike the contemporary understanding of such matches as marginal, preparatory, or frivolous, they were, in their day, the norm. Their recorded significance is closer to that of regulation games today, perhaps even greater given the fewer scheduled games played annually in the era as opposed to the number making up current league schedules. In fairness, there were often great disparities between teams in the early era, and players sometimes gave less than a full effort, hoping to “improve” the gambling odds for a return engagement. Encyclopedias and easily referenced online baseball sources provide statistics for Addy’s League and Association career but do not include perhaps his most productive years with Rockford in the 1860s.

3 Robert Addy’s umpiring appearance was in one of the last games ever played in the National Association (New York Clipper, November 6, 1875). The game in late October 1875 between the Athletic club of Philadelphia and the St. Louis Brown Stockings had been postponed several times. Addy was perhaps the only serious candidate remaining in town. He had played for the Athletics’ crosstown rival White Stockings.

4 The New York Clipper of November 24, 1877, reporting details from a New York newspaper, said, “Robert Addy, former captain of the Cincinnati Club, was dismissed from the club on Nov. 10 on the charge of dissipated habits during the past season. The facts are that Addy was not only honorably released from his engagement to the Cincinnati Club, but he was given a bonus of $100.” Other sources suggest he had assumed similar captain roles with the Philadelphia White Stockings. “Captain” was a means of describing an early manager role in this era.

5 Multiple sources over the years have fed the dubious story of Addy’s “invention” of the technique of sliding into base. A cartoon illustration from the Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, April 18, 1930, reprinted in multiple papers of the day, described him as “the first man ever to employ the slide in stealing a base in 1866.” Al Spalding was the source, but the limited range of what was then his teenage experience and travel argues against the claim’s certainty. Intriguingly, at least two Canadian newspapers, the Saskatchewan Daily Star (September 24, 1921) and the Winnipeg Tribune (December 8, 1923), told the story of Addy’s innovation, but went beyond “burying the lede” by failing to mention his Canadian identity.

6 “The second game of base ball on ice between the Franklins and picked nine [featuring Al Spalding] was played yesterday afternoon at Bob Addy’s skating rink, on the corner of Madison Street and Ada,” Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, January 17, 1878.

7 The 1861 Canadian census listed Robert Addy as a 19-year-old tinsmith. Addy’s compulsory registration in 1863 for military service during the American Civil War shows him to be a 21-year-old tinner from Canada. His 1870 US federal census listing in Rockford describes him as a 28-year-old tinsmith from Canada. This documentation confirms three things: Addy’s Canadian place of birth, birth year of 1842, and tinsmith profession.

8 In their famous 15-14 loss to the Cincinnati Red Stockings during Cincinnati’s undefeated streak in 1869-70, Addy’s cry of “how’s that,” sounding like “howzat,” was an attempt to influence the umpire’s call. See the Editorial Correspondence to the Rockford Gazette from Cincinnati, July 25, 1869. It owed much to the cricket playbook where that phrase is shouted to compel the cricket umpire to make a favorable call. In practice there is no call, since the verdict is either clear, or a player’s integrity requires him to acknowledge a result unfavorable to him. If, in the latter case, he defers from doing so, the umpire can then be called upon for a ruling. Four years later, as reported in the May 24, 1873, New York Clipper, a game between the Atlantics and Philadelphia described a hot liner hit high over Addy’s head, “but the cricketer jumped up and held it in splendid style with one hand.”

9 George and Robert Addy played for the Clipper Club of Rochelle against the Rockford Forest City featuring the 16-year-old baseball prodigy Albert Spalding, as reported in the Rockford Weekly Register-Gazette, June 23, 1866. Rockford won easily, 49-16, but Robert Addy was so impressive that he was soon playing for the Forest City. George was nearing 30 and either was no longer a prospect or had no intention of becoming one.

10 African-Canadian baseball participation dates to at least 1869 with the Lincoln Nine team from London, Ontario. No doubt they were members of original Underground Railroad-fleeing Black families. It is possible that earlier accounts of such play within one of their communities will be found. Brantford’s baseball tournament in late June 1874 featured the Foresters, an early First Nations team representing the Tuscarora, one of the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory (Guelph Evening Mercury, June 30, 1874). A female baseball club was formed in the village of Dutton in the Ontario County of Elgin (Guelph Evening Mercury, May 26, 1876). A sense of the game’s spread beyond Ontario was provided by a Guelph Evening Mercury (June 12, 1872) item entitled Base Ball in Manitoba, and by a New York Clipper item (May 3, 1873) entitled Jacques Cartier B.C. about a Montréal club composed of French-Canadians led by Charles Gauthier.

11 Thomas Gilbert’s Playing First: Early Baseball Lives at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery (Brooklyn: Green-Wood Cemetery, 2015) presents Melvin Adelman’s typology of folk and modern games. Adelman, however, did not include the crucial proto-modernity stage leading to the modern. Mike Huggins (“Associativity, Gambling, and the Rise of Protomodern British Sport, 1660-1800,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 47, No. 1, Spring 2020, 1-17) describes proto-modernity as the period preceding and preparing for “modern” sport. “It had some but not all of the features of the modern, but [was] not coherently linked in the ways described in its ideal types.”

12 Brian Turner’s “Sticks or Clubs: Ball Play Along the Route of Burgoyne’s ‘Convention Army,’” from Don Jensen, ed., Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game 11 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019), describes “bat and ball” play by both Patriots and British Army regulars. Likewise, British soldiers could have brought early baseball-type games directly into Canada without an American intermediary stop. An account from the July 1, 1841, Nova Scotian newspaper says, “Quadrille and Contra dances were got up on the green – and games of ball and bat, and such sports proceeded.”

13 The Illustrated Historical Atlas of the Counties of Northumberland and Durham, Ontario, released by H. Belden & Co. Toronto in 1878. Reprinted by Mika Silk Screening Limited, Belleville, Ontario 1972.

14 This is the spelling as given in the Belden atlas. Today the area near Brighton, Ontario, is named Presqu’lle.

15 The Dictionary of Canadian Biography describes Rogers as clerk of the peace for the newly established Newcastle District (1802), registrar of the district Surrogate Court (1802), and clerk of the district Court of Quarter Sessions (1802). This appears to confirm the identity of the court on Mr. Soper’s farm as that of a district Court of Quarter Sessions, and not the first Queen’s Bench. Here the matter sat until the 100th anniversary of Canadian Confederation in 1967, and the publication of The History of the Township of Hope, by Harold Reeve (Cobourg, Ontario: Cobourg Sentinel-Star, 1967). Reeve confirms the Hope Township’s court identity in his review of the minutes of the Quarter Sessions for Newcastle District as found in the Archives of Ontario [now located at York University in Toronto].

16 J. (John) T. Coleman, History of the Early Settlement of Bowmanville and Vicinity (Bowmanville, Ontario: West Durham Steam Printing and Publishing House, 1875).

17 Ely Playter’s diary is available on microfilm in the Public Archives of Ontario at York University in Toronto. An item dated April 13, 1803, in his fulsome penmanship, reads “I went to Town see a number of my friends walk’d out and joined a number of Men jumping and Playing Ball perceived a Mr. Joseph Randall to be the most active.” An excerpt is also found in Edith Firth, ed., The Town of York 1793-1815: A Collection of Documents of Early Toronto (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962), 248.

18 A cursory review of the Port Hope Weekly Guide uncovered five cricket matches featuring Bob Addy; there are probably more. The July 21, 1860, issue featured Port Hope and Lindsay. Port Hope won by 12 runs with Addy scoring 39 of Port Hope’s 187 runs. The July 25, 1860, Guide said of the game against Millbrook, “The batting of Mr. R. Addy of the Port Hope eleven was brilliant, his hits counting from two to four runs each.” The August 10, 1860, Guide described a game against a Peterborough eleven featuring Henry Strickland, the son of an English cricketer and nephew of two of Canada’s most noted nineteenth-century chroniclers, Catharine Parr Traill and Susanna Moodie. The August 11, 1860, Guide featured a match in which Port Hope’s first 11 played 22 other members of the club; Addy scored 52 of the first eleven’s 157 runs in a game they lost. The August 27, 1860, Guide described a game between the right- and left-handed members of the Port Hope club. The left-handed Addy did most of his team’s bowling, not surprising given the general preponderance of right-handers.

19 The Port Hope Town Directory of 1856-57 lists Mrs. Addy (Ellen), a widow for at least 10 years, and her oldest son, George, a clerk, living in a house on Harcourt Street near today’s main street, Walton, a heritage conservation district. The closest last names before and after them are Adams and Aikens. Robert and James were too young for listing. The Directory is available at the Port Hope history site at http://porthopehistory.com/1856directory/.

20 Michael Stephenson’s online Ontario Lakeshore Records Database listed an item for purchase entitled “Addy Robert, Boston baseball player, born Port Hope, Bio 1873.” The one-page sketch entitled “The Champion Right Fielder,” described its original publication in Doings of the Week the World Over and then its republication in the Port Hope Guide of November 15, 1873. It said Robert Addy was the brother of Mr. James Addy of this town.

21 The County of Durham Directory for 1869-70 (Toronto: Hunter, Rose and Co., 1869) listed James Addey [sic], occupation saddler, living in the Harcourt Street house in Port Hope. The misspelled “Addy” name was surrounded by last names of Adams and Aisthorp. James was a cricketer with the Port Hope Cricket Club and a baseball player with his town’s Silver Stars team. The latter often played against leading Ontario teams from Guelph and Kingston.

22Ida’s divorce suit against the “well-known base ball professional” said they were married August 12, 1870, and had a six-year-old child. She alleged he had kicked her in 1873, threatened her life with a razor blade in 1876, and had committed “several distinct adulteries.” The report in the Rockford (Illinois) Daily Register of March 12, 1880 said that if this was true, “Bob is a brute and villain and deserves to suffer something worse than separation from a bright, intelligent and long-suffering wife.” Two years later the same paper (April 26, 1882) reported, however, that the suit had been dismissed by Ida at her costs.

23 We know about Ida’s previous and subsequent life because of a fortuitous act of bravery by her second husband, Jerry Kinney, a conductor on the Oregon Short Line. Kinney’s train struck a rancher, Mr. H.W. Leaden-wall, who was hurled into a nearby river. Conductor Kinney rescued Leadenwall, and the railroad man was said to be eligible for a Carnegie Medal for bravery. In reporting the incident, even from a great distance, the Rockford Republic of October 21, 1908, said, “The wife of Mr. Kinney is a former Rockford girl. Miss Ida Seeley having left here as the wife of Bob Addy, the celebrated ball player….” Now that her new name was known, follow-up investigation through Ancestry.com, Genealogy Bank, and Newspapers.com was straightforward. Her marriage to Kinney and the birth of a son soon after appear to have brought a quick, “no-fault” resolution to divorce proceedings against Addy. Her family, future prosperity, and long life are well documented.

24 The Canadian Gentleman’s Journal and Sporting Times, November 23, 1877, stated, “The announcement recently made that Robert Addy, the Canadian ball player had been dismissed from the Cincinnati Club and that Foley was also to be thrown out, appears to be untrue.” As late as 2004 in a reprint of The Boston Braves 1871-1953, by Harold Kaese (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), but originally published in 1948, it was said of Addy’s background on joining the Boston Red Stockings: “…Robert Addy, a Canadian, who had not played since 1872, but previously starred for the Forest Citys….” (page 11).

25 “The 10 man team departed Rockford May 17 [1870], accompanied by George Haskell as business manager (or traveling secretary); James Manny, Will Barbour, and CM. Utter, all helping out rather than merely along for the ride. Also with the team was a reporter for the Rockford Register who signed himself only as ‘N.’ The first games were easy and overwhelming victories over the Hamilton Maple Leafs (Ontario, Canada) [May 18, 1870], the Buffalo Niagaras, and the Syracuse Eckfords. In Hamilton the locals discovered Bob Addy was Canadian-born ‘and he was the object of special pride on the part of the Canucks, they claimed him from the start as one of them,’ which immediately made the star the target of jibes from his teammates: ‘I don’t care nothing for ’em,’ he exclaimed, ‘I tell you I don’t care nothing about ’em.’” From Nuggets of History, Volume 47, Number 3, September 2009: “The Eastern Tour of the 1870 Season for the Forest City Baseball Club” by John Molyneaux. The account originally appeared in the Rockford Register May 23, 1870. Perhaps Rockford’s 65-3 victory over the Hamilton Maple Leafs was an additional factor in Addy’s not wanting to be associated with a Canadian fandom.

26 The most definitive account of the Addy family’s Port Hope connections is found in the Surrogate Court Index of Ontario, Canada (1859-1900), Vol. 4 Northumberland and Durham Counties on microfilm at the Ontario Public Archives, based at York University in Toronto, in Cabinet 2 of the Archives Reading Room. Robert Addy and George Addy (and their known locations) are principal executors for their mother Ellen Addy (Probate number 2593, Probate date 1889, reel number 569) and their younger brother James Addy (Probate number 2185, Probate date 1886, reel number 566).

27 Several exercises were undertaken toward the end of the nineteenth century to uncover the current location of men (women were noticeably absent from such lists) who had once lived in Port Hope. The July 5, 1889, issue of the Port Hope Weekly Guide featured an article under the heading “Our Wandering Boys,” and subtitled The Export of Blood, Brains and Bones, A Partial List of Our Young Men Who have Gone to Better their Condition in Uncle Sam’s Domain. Robert Addy was said to be in New York, but this was incorrect; by then he had settled in the American West. A second list of “Old Boys” claimed to name those who returned for a 1901 reunion. It was compiled by Joseph Hooper, and indicated where the “Old Boys” were apparently living at that time. It included the brothers George Addy from Philadelphia, and Robert Addy from Salt Lake City in the Utah Territory. By then, however, Robert was living in Pocatello, Idaho, and almost certainly he and George did not attend the reunion. Source for the latter: http://porthopehistory.com/1901reunion/.

28 Multiple sources listed Bob Addy’s death on April 10, 1910, including the Rockford Daily Register-Gazette (April 11, 1910). Bob Addy’s last home at 507 N. Garfield in Pocatello, Idaho, is today described as a two-story home combining Colonial Revival massing, low-pitched roof and eave overhangs reminiscent of the Prairie Style, and Victorian/Queen Anne features in its rounded bay, porch encircling two sides of the first story and fenestration. Recognized as the Addy House in a walking tour guide, it is included in the Pocatello Westside Residential Historic District, as listed by the US Department of the Interior National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places. Ironically, Bob’s old house in Port Hope straddles that town’s heritage district.

29 Frank Lander, “Bob Addy Was Talkative on Forest Citys,” Rockford Morning Star, April 18, 1930.

30 Twenty-four-year-old Sara E. Addy of Illinois married 58-year-old George Reading of Port Hope on July 17, 1888, in Port Hope, as listed in the Schedule B of Marriages for the County of Durham, Division of Port Hope.

31Frederick Cook, Through the First Antarctic Night, 1898-1899 (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1909), in which Arctowski and Roald Amundsen, the famed Norwegian explorer, provided a breakdown of their crewmates’ votes for the most beautiful women. Henryk and Jane would later become close friends of Robert Scott and his wife, the sculptor Kathleen Bruce (Cincinnati Post, February 15, 1913). Scott was the ill-fated English adventurer who died on his return journey, having reached the South Pole shortly after Amundsen’s historic first. Jane Arctowska (the feminine spelling in Polish) treasured the gift of a silk scarf presented to her by Scott (p. 295-296).

32 One of which was Antoni Choloniewski’s The Spirit of Polish History, translated by Jane (Addy) Arctowska, The Polish Book Importing Co., Inc., 1918.

33 Correspondence between the US Department of State and the American Security and Trust Company dated April 6, 1960, discussed arrangements for sending the cremated remains of Jane Arctowska and her husband, Professor Henryk Arctowski, to Poland for a ceremony and burial. National Archives at College Park; College Park, Maryland, U.S.A.; NAI Number: 302021; Record Group Title: General Records of the Department of State; Record Group Number: Record Group 59; Series Number: Publication A1 205; Box Number: 386; Box Description: 1960-1963 Poland A-Z. Available on Ancestry.com.