Safe at Home: Babe Ruth at ‘The House That Ruth Built,’ 1939-1948

This article was written by Dan Neumann

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

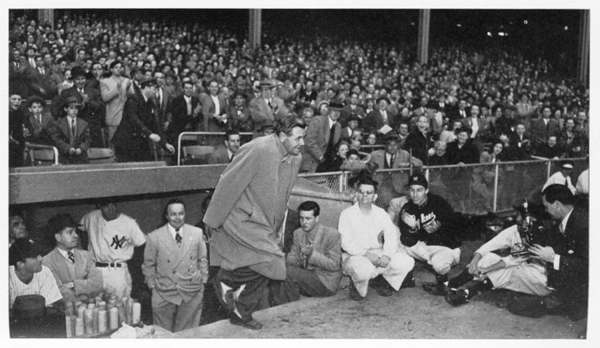

On September 28, 1947, the Bambino made an appearance before a game benefitting his Babe Ruth Foundation – later recognized as the first Old-Timers Day. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

The story of Yankee Stadium cannot be told without telling the story of Babe Ruth. His home-field exploits during his playing days are well covered, but a study of his later appearances at the Stadium is equally valuable. Each unique its own way, these appearances provide valuable insight into Ruth as a player, a teammate, a celebrity, and an American icon.

The Babe left the Yankees after the 1934 season, playing one year in Boston before retiring as a player in 1935. His relationship with the Yankees was strained in the ensuing years, and he did not formally return to Yankee Stadium until the famed Lou Gehrig Day in 1939. For the next decade, until his death in 1948, Ruth appeared at the Stadium on several occasions, each time to thundering ovations from throngs of adoring fans.

LOU GEHRIG DAY (JULY 4, 1939)

Ruth left the Yankees after the 1934 season, spending a few months with the Boston Braves in 1935 before quitting as a player. Frustrated at his lack of managerial opportunities, Ruth kept his distance from the game, and was rarely seen at Yankee Stadium during the latter half of the 1930s. In 1936, when Ruth asked for tickets to Opening Day, he was instructed to send a check to the team offices.1 By the late 1930s, the relationship between the team and its most legendary player was clearly a strained one.

Ruth and Lou Gehrig were teammates on the Yankees from Gehrig’s debut in 1923 until Ruth left the team. The had not spoken in five years, with the cause of the rift never definitively determined. The two had even traded barbs in the press a few years earlier.2 In early 1939 Gehrig announced his retirement after being diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the illness that would eventually take his life. The Yankees organized a Lou Gehrig Day in Gehrig’s honor between games of a doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers on July 4. The 1927 Murderers Row team was invited to return to the Stadium and honor their captain. Attendees included future Hall of Famers Tony Lazzeri, Waite Hoyt, Earle Combs, and Herb Pennock, as well as Wally Pipp, the first baseman whose injury famously made a place for Gehrig in the Yankees lineup. Retired pitcher George Pipgras was also there, although the trip was less arduous for him than for the others. Pipgras was now an American League umpire and was assigned to work that day’s doubleheader.3

Ruth arrived late to the proceedings, dressed in a white suit and two-tone shoes, and sporting a dark tan.4 Several men gave speeches paying tribute to Gehrig, including Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Postmaster General James Farley, and Yankees manager Joe McCarthy.5 Ruth then gave a brief speech praising Gehrig and expressing his belief that, even in 1939, he and his former teammates would defeat the present-day team.6 The two men shook hands, and Ruth wrapped his arms around Gehrig in an embrace. Gehrig then delivered his famous “Luckiest Man” speech.7

The Ruth/Gehrig hug has been the source of debate in the ensuing years. The day (and Ruth’s gesture) is often cited as bringing an end to the feud between the two men. Biographer Robert Creamer writes that the embrace “ended the long antagonism” between the two men.8 Others, including Hall of Fame catcher Bill Dickey, were more skeptical. Discussing a picture of the two on that day, Dickey said that “if you look close, Lou never put his arm around the Babe. Lou just never forgave him.” The two, Dickey claimed, were “never friends again.”9 Pictures from that day do show Gehrig’s arm around Ruth, albeit with a grasp much looser than the Babe’s. Gehrig’s grin is rather sheepish, compared to the beaming Babe. Whether or not this evidences a dislike for Ruth would be impossible to determine. Gehrig’s personality was naturally less gregarious than Ruth’s, even when putting aside the emotion of the day and Gehrig’s natural sadness and exhaustion accompanying his illness and the end of his career.

The two were photographed together at the 1939 World Series in Yankee Stadium, but it is unclear how often (if at all) the two visited prior to Gehrig’s death in June 1941.10

RUTH BATS AGAINST WALTER JOHNSON TO BENEFIT THE WAR EFFORT (AUGUST 23, 1942)

With American entry into World War II, Ruth frequently donated his time to raising money for the war effort. He played a series of golf matches against Ty Cobb to benefit war charities and bowled against New York Giants football star Ken Strong for the same purpose.11 He visited veterans hospitals and sent recorded messages to the troops.12 Ruth’s part in the war was not limited to his roles as a fundraiser and a morale booster. A widely circulated story at the time told of Japanese soldiers shouting “To hell with Babe Ruth!” as they attacked American soldiers. Upon hearing this, Ruth angrily destroyed most of the souvenir items he had brought back from his barnstorming trip to Japan a decade earlier.13

In 1942 Ruth returned to a more familiar sport in a charity benefit at Yankee Stadium. Donning the Yankees uniform for the first time since 1934, Ruth batted against legendary pitcher Walter Johnson in a fundraiser for the Army-Navy Fund. Ruth hit Johnson’s fifth pitch into the right-field stands. The 20th pitch was driven into the upper deck, although just foul. This was good enough for the Babe, however, as he circled the bases, doffing his cap to the crowd of over 70,000.14 “I knew I couldn’t top that,” Ruth said later.15 Together Ruth and Johnson raised more than $80,000 for the Army-Navy Fund.16

While clearly the highlight of the fundraiser, the matchup between the two legends was only part of the day’s special activities. Yankees and Senators players took part in several athletic competitions. Senators George Case and Johnny Sullivan were victorious in a sprint over Tuck Stainback and Johnny Lindell. The two also joined Mickey Vernon and Ellis Clary on a victorious sprinting team over Charlie Keller, Tommy Henrich, Joe Gordon, and George Selkirk. Washington Senator Al Evans won the accuracy throwing contest for catchers (defeating Bill Dickey among others) and tied for the lead in a “barrel pitching” contest. Only Yankees pitcher Norm Branch was victorious in an event. He won the fungo-hitting contest with a distance of 376 feet.17

RUTH’S LAST “GAME” IN YANKEES PINSTRIPES (JULY 28, 1943)

Pitcher Johnny Sain is perhaps best known as one half of the “Spahn and Sain” duo on the Boston Braves of the late 1940s. He won 20 games four times for the Braves and was a three-time World Series winner with the Yankees of the early 1950s. He is also the answer to a somewhat misleading trivia question, as he is cited as the first pitcher to face Jackie Robinson in the major leagues, and the last to pitch against Babe Ruth in an organized game.18

The Robinson piece is true enough, as Sain was the starting pitcher for the Braves against the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. The Ruth piece is a bit more misleading. In July 1943, while serving in the military, Sain was pitching in an exhibition game at Yankee Stadium against a team managed by Ruth. Ruth inserted himself as a pinch-hitter against Sain, hitting one long foul before walking.19 “Between me and the ump, we walked the Babe,” Sain said years later.20 Ruth initially refused a pinch-runner, and the next batter singled. After coming up “lame and puffing,” in the words of biographer Robert Creamer, Ruth submitted to the pinch-runner and jogged off the Yankee Stadium field. It was his last appearance in a formal game at Yankee Stadium.21

BABE RUTH DAY (APRIL 27, 1947)

Hospitalized and diagnosed with throat cancer in late 1946, Ruth had less than 18 months to live by the time the 1947 baseball season began. Commissioner Happy Chandler declared April 27 to be Babe Ruth Day in all major-league ballparks, with the minor leagues soon following suit. No baseball figure had been honored with a national commemoration day since Harry Wright in 1896.22 Only two years after the end of World War II, when Japanese soldiers were shouting “To hell with Babe Ruth!” the Bambino was also honored with ceremonies in Tokyo and Osaka.23

The ceremony that day lasted only 10 minutes, with speakers including Cardinal Francis Spellman and Commissioner Happy Chandler. Chandler was loudly booed by the New York fans because of his recent one-year suspension of Dodgers manager and one-time Ruth roommate Leo Durocher for associating with gamblers.24

With his voice ravaged by cancer, Ruth began his speech by noting that “you know how bad my voice sounds, well it feels just as bad.”25 He had not prepared a speech, and his extemporaneous remarks were largely a tribute to the game he loved: “You know this baseball game of ours comes up from the youth. That means the boys. And after you’ve been a boy and grow up to know how to play ball, then you come to the boys you see representing themselves today in our national pastime. The only real game in the world, I think, baseball.”26 The speech, which was broadcast to every ballpark in the major leagues where a game was being played that day.27 brought tears to the eyes of the 58,339 assembled fans. Longtime Yankees general manager Ed Barrow, who had also managed Ruth with the 1918 Red Sox, had retired earlier that year but attended the ceremonies at Yankee Stadium that day. He refused to go down onto the field. “I never did like to cry in public,” Barrow told a reporter.28

THE “OTHER” BABE RUTH DAY (SEPTEMBER 28, 1947)

Largely forgotten between the Babe Ruth Day of April 1947 and the Babe’s final appearance of June 1948 is the second “Babe Ruth Day,” held in September 1947 to benefit the Babe Ruth Foundation. Ruth had established this foundation earlier in 1947 to benefit underprivileged children.29 In the months since his April appearance, doctors had begun treating Ruth’s cancer with an experimental drug. He had improved rapidly and had begun traveling the country doing promotional work on American Legion baseball for the Ford Motor Company.30 So remarkable was Ruth’s improvement that he hoped to pitch an inning during the September game. In actuality, the “miraculous recovery” was merely a temporary remission of the Babe’s cancer. By late September his health was in decline again and he was forced to watch the game from the stands.31

Ruth’s former teammates and adversaries traveled to Yankee Stadium to attend or play in the game. These included future Hall of Famers Waite Hoyt, Earle Combs, Harry Hooper, Tris Speaker, Jimmie Foxx, Charlie Gehringer, and even the 80-year-old Cy Young.32 A contemporary newspaper account described the event as “one of the most remarkable pageants ever seen in a baseball arena.”33 The most memorable performance came from Ty Cobb, who was flown from Nevada to New York on Yankees owner Del Webb’s private plane.34 Cobb, now 60 years old, led off the game in the first inning. He turned to catcher Wally Schang and said, “Would you mind backing up a bit? I’m an old man now, and I can barely hold on to this bat. I am worried I will hit you with it.”35 Schang respectfully obliged, only for Cobb to lay down a bunt and attempt to beat it out for a hit. He missed by only a step. After the game, Cobb and Ruth were photographed together for the last time. In his book on the relationship between the two men, author Tom Stanton writes, “Whether from pain or medication or emotion, Ruth’s eyes were wet when Cobb laid his hand on Ruth’s right shoulder. The moisture caught the flash of the camera.”36

A few days later, Ruth, Cobb, and Young attended Game One of the 1947 World Series at Yankee Stadium. The fans stood and applauded Ruth after the National Anthem. Wearing an oversized camel’s-hair coat and smoking a cigar, Ruth gingerly stood and waved to the crowd.37

RUTH’S FINAL YANKEE STADIUM VISIT AND NUMBER RETIREMENT (JUNE 13, 1948)

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of Yankee Stadium, the Yankees scheduled a celebration on June 13, 1948. The centerpiece of this celebration was the retirement of Ruth’s number 3. Nearly ubiquitous in twenty-first-century American sports, number retirements had not yet attained their place in the American consciousness. Only Gehrig and Giants pitcher Carl Hubbell had been so honored in baseball, joined by a handful of players in the NFL and NHL.38 In the decade and a half since Ruth left the team, the number had been worn by journeymen like Bud Metheny, Eddie Bockman, Roy Weatherly, Allie Clark, and Frank Colman.39 The current wearer was outfielder Cliff Mapes, who switched briefly to number 13 before settling on 7, a number he wore until he was traded to Detroit in 1951. Later that same year, Mickey Mantle donned number 7, making Mapes one of the last Yankees to wear 7 before it was retired.40

The cool, rainy weather set the stage for what one Ruth biographer has described as a “maudlin ceremony.”41 Several of Ruth’s teammates had died young, including future Hall of Famers Lazzeri, Pennock, and Gehrig.42 Members of the 1923 team (the first to call Yankee Stadium home), participated in a two-inning exhibition against “old-timers” from later Yankees teams. Participating members of the ’23 team included Waite Hoyt, Wally Pipp, Carl Mays, and Wally Schang, who was likely glad Ty Cobb was not playing in this game.43 The latter-day team included Red Rolfe, Mark Koenig, and the still-active Joe Gordon, a former Yankee then a member of the visiting Cleveland Indians. Far from an old-timer, Gordon was an All-Star in 1948 and would help lead the Indians to a World Series victory a few months later. “Once a Yankee, always a Yankee,” said Hoyt.44

Mel Allen, who broadcast games for the Yankees until 1985, emceed the proceedings. Ruth waited in the clubhouse until it was nearing the time for his name to be announced. Moving into the dugout, he spotted a fielder’s mitt and picked it up. “You could catch a basketball with this,” he quipped.45 His name finally announced by Allen, Ruth “walked out into the cauldron of sound he must have known better than any man,” in the words of sportswriter W.C. Heinz.46 He spoke only briefly, expressing his pride at having hit the first home run in Yankee Stadium history. After the ceremony, Ruth sat in the locker room drinking a beer with his friend and former teammate Joe Dugan. “How are things, Jidge?” Dugan asked, using the nickname (a variation of George) common among Ruth’s teammates. “Joe, I’m gone,” Ruth replied. The two men began to cry.47 The Babe never returned to Yankee Stadium in his lifetime.

The most enduring image of that day is a photograph of Ruth, standing on the third-base side of home plate, with Bob Feller’s bat in his hand to support himself, his number 3 jersey on his still broad shoulders. The Yankees had dressed on the third-base side clubhouse during Ruth’s playing days but had moved to the first-base side prior to the 1946 season. Since Ruth’s old locker had not been moved, he dressed in what was now the visitors’ clubhouse, and entered the field through the Indians’ dugout. First baseman Eddie Robinson, who would one day play for the Yankees and lived long enough to start his own podcast prior to his death in 2021, worried about Ruth’s stability in climbing the dugout stairs. “He just looked wobbly,” Robinson later recalled.48 Robinson handed the Babe a bat to steady himself, one that belonged to Bob Feller.49

Later titled “The Babe Bows Out,” the picture was taken by Nat Fein, a substitute photographer for the New York Herald Tribune. While most photographers had positioned themselves in front of Ruth on the baseline, Fein chose to photograph the Babe from the back. “The number 3 was the thing I was interested in,” Fein would say. “I felt the only way to tell the story of Babe retiring was from the back.”50 The picture appeared on the front page of the Herald Tribune the next day and was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. Life Magazine would describe it as “one of the greatest pictures of the 20th Century.”51

THE BABE’S FUNERAL (AUGUST 17 AND 18, 1948)

The Babe succumbed to cancer on the evening of August 16, 1948. The original suggestion had been to hold Ruth’s wake at the Universal Funeral Home on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, but the Babe instead would lie in state at Yankee Stadium for two days, on August 17 and 18.52 Ruth’s daughters had originally objected to the plan, based both on Ruth’s treatment by the Yankees after his retirement, and on a desire to protect their father’s image. “Poor Daddy, he looked so awful,” his daughter Julia would say. “I hated to think of all those people going by and seeing him looking like that. He looked so old, so sad.”53

Ruth’s casket arrived at the Stadium in the mid-afternoon of August 17. His wife, Claire, and her daughter, Julia, whom Ruth adopted as his own, attended. Dorothy Ruth, the Babe’s biological daughter from a previous relationship, did not. She was estranged from her stepmother and stepsister.54 Speaking of that day, Julia later said, “It was quiet. As quiet as you could get in New York City. And bare. Absolutely bare. There were flowers. There was light.”55 The gates opened at 5:00 P.M., and while they were originally scheduled to close at 10:00 P.M. (reopening the next morning), an announcement was soon made that the gates would remain open all night to allow all mourners their chance to bid the Babe goodbye.56

The next morning, charter buses arrived from Maryland, Delaware, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. Vendors sold hot dogs and pictures of the Babe.57 VIPs included entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Hank Greenberg and Leo Durocher.58 A 26-year-old man who had lost his leg in World War II told reporters that when he was a student at St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Poughkeepsie, New York, Ruth had taken him and 250 of his classmates to a game at Yankee Stadium.59 Also among the mourners was 3-year-old Harry Escobar, wearing a full Yankees uniform and a black armband his father had taped around his left sleeve. Young Harry’s picture adorned the picture of the New York Daily News the next day, with a headline reading: “Ruth’s Last Gate, His Greatest.”60

The Stadium that Ruth played in stood for another quarter-century after his death, before undergoing a major renovation in the 1970s. The renovated park was finally torn down in 2009, replaced by the current version of Yankee Stadium. Many American heroes would appear at Yankee Stadium through the years, not just in baseball but in other sports and other walks of life. Yet Babe Ruth remains the only one to lie in state at the Stadium, the only one given credit for “building” the iconic ballpark. The outpouring of love for him over those two days in August of 1948 is evidence of his singular place in the hearts of Yankees fans then and now.

A lifelong Yankees fan, DAN NEUMANN lives in Crofton, Maryland, with his wife, son, and dog. With his brother Andrew, he co-hosts the Hello Old Sports podcast on the Sports History Network, covering any and all topics related to sports history from the 1869 Red Stockings to the 1990s NBA. He is a member of SABR and the Professional Football Researchers Association. During the day, he works for the Federal Aviation Administration and teaches part-time for the Boston University Washington Internship Program.

NOTES

1 Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Penguin, 1988), 405.

2 Jonathan Eig, Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 223.

3 Frank Graham, The New York Yankees: An Informal History (New York: Putnam, 1947), 252.

4 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 354.

5 Eig, 315.

6 Paul Hofmann, “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day: Ruth and Gehrig End Feud,” in Bill Nowlin and Glen Sparks, eds., The Babe (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2019), 296.

7 Tara Krieger, “Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig,” in The Babe, 93.

8 Creamer, 415.

9 Krieger in The Babe, 93.

10 Krieger, 93.

11 Montville, 355.

12 Ruth’s message to the troops, which accompanied a highlight film of the 1943 World Series, can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8VOUh1aoKU.

13 Montville, 355.

14 Jane Leavy, The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), 431.

15 Henry Thomas, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Washington: Random Press, 1995), 342.

16 Leavy, 431.

17 James Dawson, “Ruth, Johnson Turn Back Clock; Fans See What Made Them Click,” New York Times, August 24, 1942: 19.

18 Matt Schudel, “Pitcher Johnny Sain, 89, Hurled His Way into History,” Washington Post, November 9, 2006. Accessible online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2006/11/09/pitcher-johnny-sain-89-hurled-his-way-into-history/2c37bf0a-7705-4b88-acd7-0fe3f5e7dbc1/.

19 Creamer, 417.

20 Schudel, “Pitcher Johnny Sain, 89.”

21 Creamer, 417.

22 Marty Appel, Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees From Before The Babe to After The Boss (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 260.

23 Joe Schuster, “Babe Ruth Day,” in The Babe, 299. (Ruth was in New York and did not attend the ceremonies in Japan.)

24 Schuster, 299.

25 Montville, 359.

26 Creamer, 419.

27 Schuster, in The Babe, 299.

28 Appel, 261.

29 Creamer, 420.

30 Creamer, 420.

31 Creamer, 420.

32 Stanton, 235.

33 ” Old-Timers Game Goes to Yankees,” New York Times, September 27, 1947: 25.

34 Tom Stanton, Ty and the Babe: Baseball’s Fiercest Rivals: A Surprising Friendship and the 1941 Has-Beens Golf Championship (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2007), 235.

35 Joe Posnanski, The Baseball 100 (New York: Avid Reader Press, 2021), 736.

36 Stanton, 236.

37 Kevin Cook, Electric October: Seven World Series Games, Six Lives, Five Minutes of Fame That Lasted Forever (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2017), 100.

38 Appel, 269.

39 Appel, 269.

40 Appel, 269.

41 Montville, 363.

42 Montville, 363. Gehrig died at 37 in 1941, Lazzeri at 42 in 1946, and Pennock at 53 in 1948.

43 Appel, 269.

44 Appel, 269.

45 Montville, 363.

46 Glen Sparks, “Babe Ruth Makes Final Visit to Yankee Stadium,” in The Babe, 302.

47 Creamer, 423.

48 Leavy, 455.

49 Leavy, 455.

50 Sparks, in The Babe, 303.

51 Sparks, in The Babe, 303.

52 Montville, 366.

53 Leavy, 468.

54 Leavy, 469.

55 Leavy, 469.

56 Leavy, 469.

57 Leavy, 469.

58 Leavy, 471.

59 Leavy, 469.

60 Leavy, 472.