Salary Arbitration: Burden or Benefit?

This article was written by Bill Gilbert

This article was published in 2006 Baseball Research Journal

The salary arbitration process is not well understood and it is frequently described in a negative way by media, as well as the clubs and players. I hope to improve the understanding of the process and how it works in this article.

Salary arbitration was instituted as part of the collective bargaining agreement between the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) and Major League Baseball (MLB) in the early 1970s. The purpose was to provide a system for players not yet eligible for free agency to be compensated based on a comparison with their peers.

The first hearings were held in 1974. The highest number of cases filed in any year was 162 in 1990. In 2007, 106 cases were filed with 99 being settled before a hearing was held. The number of cases that actually went to an arbitration hearing peaked in 1986 (35). Over the years, 476 cases have been heard by arbitrators with the clubs winning 273 (57%) and the players winning 203 (43%).

Eligibility for Salary Arbitration

Two classes of players are eligible for salary arbitration. The first class is players with 3-5 years of major league service (MLS) and the top 17% in seniority of MLS-2 players. This class accounts for over 90% of the cases filed with most of them involving players with 3 or 4 years of major league service.

The second class of eligible players includes free agents with 6+ years of ML service. Clubs have the option to offer arbitration to free agents who were with the club the previous season and these players then have the option of accepting or declining. If the player accepts arbitration, he is bound to the club and is no longer a free agent. Cases involving this class of players rarely go to a hearing. When Todd Walker won his arbitration case in 2007, he was the first MLS-6+ free agent to go to a hearing since 1991 when Dickie Thon, Jim Gantner and Dan Petry, all with 11+ years of MLS, went to hearings and lost.

The Arbitration Process

The arbitration process enables clubs to retain control of players with less than six years ML service, while the advantage to the players is that they receive salaries that are influenced by the market and their performance. The benefit to both sides is that the process is designed to promote a settlement without a hearing. If a case goes to a hearing, the arbitrators must award either the player’s filing or the club’s filing—there’s nothing in between. Thus both sides are taking a substantial risk if they allow a case to go a hearing. In the last 10 years, over 90% of the cases filed have settled prior to a hearing.

Of the 106 players who filed for salary arbitration in 2007, 50 reached contract agreements with their clubs before players and clubs exchanged salary figures on January 16. Of the remaining 56 cases, only 7 went to hearings with the clubs winning 4 and the players winning 3. The other 49 cases were settled prior to the hearings, as follows:

- 10 players signed multi-year contracts.

- 4 players signed one-year contracts for a figure above the mid-point of the two figures.

- 12 players signed one-year contracts at the mid-point.

- 23 players signed one-year contracts below the mid-point.

This is the way the arbitration process is supposed to work, with very few cases going to hearings. Players eligible for arbitration for the first time typically are in a position to negotiate a large increase in salary since the possibility of arbitration gives them leverage that they didn’t have in their pre-arbitration years when their salaries are under control of the clubs. Players who have been through the process before also generally receive salary increases depending on their performance in the preceding year.

Conduct of a Hearing

A hearing panel consists of three arbitrators with one designated as the chairperson. Others present include the player (and sometimes his wife), his representatives and representatives from the MLBPA. Respected baseball analysts like Bill James and Gary Skoog have been used in hearings and several former players; Phil Bradley, Bobby Bonilla, Mark Belanger, Mike Fischlin and Tony Bernazard among others, have been employed by the MLBPA and have been present at hearings. The club is represented by an official, usually the general manager, and also typically by an experienced arbitration practitioner to present the case. Others present are representatives from the Labor Relations Department of MLB, usually including General Counsel Labor, Frank Coonelly.

The player is given one hour to present his case followed by an hour for the club to present its side. After a break to prepare rebuttals, each side is allowed 30 minutes for rebuttal. The arbitrators then have 24 hours to render their decision. There has been at least one occasion where a case was settled after a hearing. In a 1994 case involving the Houston Astros and relief pitcher, Tom Edens, the hearing was held with both sides anticipating a decision the following day. However, in the evening after the hearing, the agent for Edens called Bob Watson, then the Houston General Manager, and suggested that they settle at the mid-point of the filings. Watson agreed and the arbitrator (there was only one back then) was relieved of the responsibility of reaching a decision.

Arbitration Criteria

The collective bargaining agreement is specific regarding what is admissible and non-admissible in a hearing. Admissible items include the quality of the player’s performance, the length and consistency of his performance, his record of past compensation, any physical or mental defects and comparative baseball salaries. The arbitrators are directed to give particular attention to contracts of players not exceeding one service group above that of the player.

Non-admissible items include the financial position of the player or the club, press comments on the player’s performance and prior offers by either side.

Arbitration Hearing Strategies

In the player’s case, emphasis is given to the strength of his performance and his awards or achievements. He is compared with players in the same service class with high salaries. The objective is to build evidence that supports a salary higher than the mid-point in the case. Sometimes another player will be brought in to testify in support of the player. A classic example was the 1998 Charles Johnson case when Scott Boras brought in Kevin Brown to testify that he had pitched to both Johnson and Ivan Rodriguez and that Johnson was better at working with pitchers. In his 1994 case vs. Kansas City, Brian McRae also benefited from first-hand testimony about his defense by David Cone and Willie Wilson.

The challenge of the club is to point out deficiencies in the performance of the player without personally demeaning the player. This is tricky but it is essential since the player is part of the club. The club can point out the lack of awards and achievements and will strive to compare the player with players in the same service class with relatively low salaries. The objective is to build evidence that supports a salary lower than the mid-point in the case.

In a typical case, each side will use a different group of players they deem comparable to support their cases. An exception was the 1994 Brian McRae case. It was the last hearing on the 1994 docket so essentially all other relevant salaries had been established. Both sides used exactly the same group of National League outfielders as comparables, all with three years of MLS and one-year contracts for 1994 at salaries close to the mid-point of $1.6 million in the McRae case. The players were Ray Lankford, Moises Alou, Luis Gonzalez, Orlando Merced and Bernard Gilkey. McRae’s agent argued that his player’s performance placed him among the leaders in this group and the Club argued that his performance did not measure up to these players. McRae won the case (but subsequent years have shown that he probably ranked last in this group on a career basis).

Arbitration Hearing results

The trend in recent years is for more cases to be settled prior to hearings. This is due to several reasons, one of which is that both sides now have a better grasp of a player’s value in the arbitration process and file accordingly, anticipating a settlement around the mid-point:

Average # % Won by

Hearings/Yr Players

1980–1992 21 45%

1993–2001 11 37%

2002–2007 6 34%

Clubs have won a majority of decisions in each of the last 11 years.

Salary Case Studies

These three examples illustrate how a player’s salary may change as he moves from club control in his first three years, through arbitration, to his eligibility for free agency after six years.

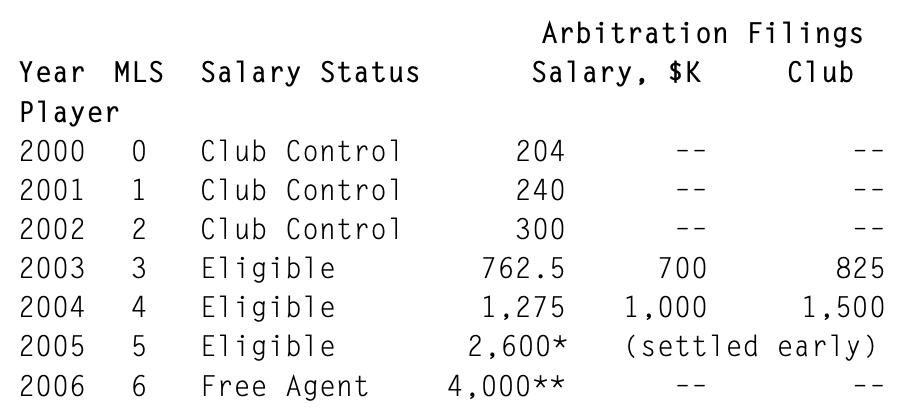

B.J. Ryan

Ryan’s case is typical of a player whose role and performance increases as he moves through his arbitration years. In his first two arbitration years, he settled with Baltimore near the mid-point before a hearing, and in the third year a salary was agreed upon before figures were exchanged. Ryan became a very effective closer in 2005 and signed a five-year contract with Toronto when he became a free agent after six years.

*Earned an additional $225K in performance and awards bonuses.

**First year of five-year, $47M contract.

Michael Barrett

Barrett was one of the fortunate players who became eligible for free agency as an MLS-2. In his first two arbitration years, he agreed on a contract with Montreal before figures were exchanged. However, his career hit a bump in 2003 when hebatted .208 and lost his job as the starting catcher. He was traded to the A’s and then to the Cubs who did not tender him a contract. This took away the leverage he would have had as an arbitration eligible player and the Cubs signed him to a contract with a salary far below what he was paid the previous year. He responded with a breakout season and signed a three-year contract with the Cubs in his final year of arbitration eligibility after figures were exchanged.

*First year of three-year., $12M contract. Earned an additional $50K award bonus.

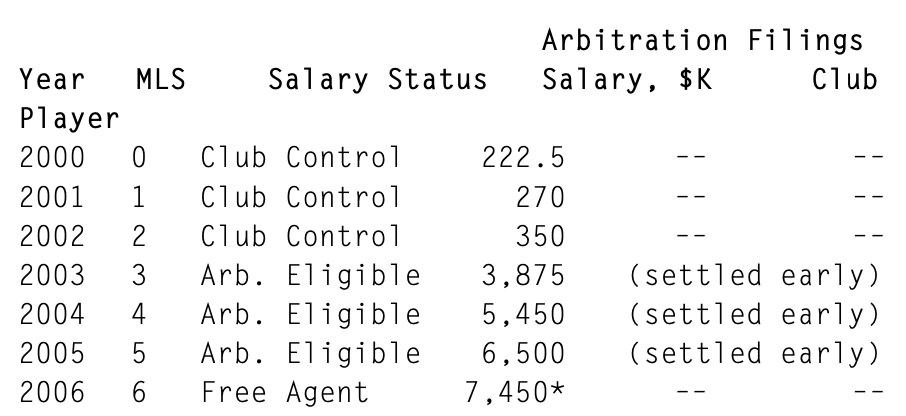

Jarrod Washburn

Washburn had a big year (18-6, 3.15 ERA) prior to his first year of arbitration eligibility. This gave him the leverage to command a big contract as an MLS-3. His salary continued to increase the next two years when he was essentially an average major league starting pitcher. In all three of his arbitration years, he settled on a contract with the Angels before figures were exchanged. He signed a four-year contract with Seattle when he became a free agent after six years.

*First year of four-year, $37.0 M contract.

Conclusions

- The arbitration process provides benefits to both clubs and players.

- Clubs retain player control for 6 years.

- Players receive market-influenced salaries 3 years before free agent eligibility.

- The process has been in place since 1974 and has survived numerous labor negotiations.

- The vast majority of salaries are determined by the process, not by an arbitration award.

A SABR member since 1984, BILL GILBERT has given 11 presentations at SABR Conventions and has also written articles for The National Pastime, The Baseball Research Journal, and other publications.