Satchel Paige: Twilight with the Marlins

This article was written by Alan Cohen

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

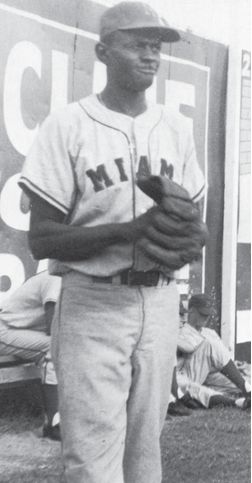

Satchel Paige, shown here in Miami uniform, was brought to the team by executive vice president Bill Veeck, for whom he had pitched in the major leagues with Cleveland and St. Louis. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

At the end of the 1956 season, writer Oscar Fraley observed that Satchel Paige was “a rounders robot who reportedly inspired Abner Doubleday to invent baseball.”1 That was after Paige had—at age 50—gone 11–4 with two shutouts, 13 saves, and a 1.86 ERA for the Miami Marlins of the International League.2 Paige spent three seasons with the Marlins, which were both successful and controversial.

The story of how, quite by accident, the International League wound up in Miami was recounted by Bill Veeck some years ago. In 1955, Syracuse had drawn 85,191 fans, by far the least of any Triple-A team. Their owner wanted out. One night, at a restaurant in Columbus, Ohio, the owner heard Sid Salomon say, “If I could buy a club, I wouldn’t hesitate to move it to Miami.” Soon thereafter, Salomon had himself a ball club, and hired his close friend Veeck to run the organization.3

Veeck, as the Marlins’ Executive Vice-President, signed Satchel Paige to pitch for the team. Satchel had first pitched for Veeck with the Indians in 1948, and had also pitched for him with the St. Louis Browns from 1951 through 1953. When the Browns moved on to Baltimore in 1954, both Veeck and Paige had joined the ranks of the unemployed. For two years, Paige pitched in exhibitions and did a stint with the Kansas City Monarchs, but was out of Organized Baseball.

The hiatus ended on Opening Day 1956, as 8,806 fans came to Miami Stadium to see the new team in town complete with the usual Veeck trimmings. Paige was supposed to arrive at the mound via helicopter prior to the first pitch, but things got a bit disorganized. He arrived in a cloud of dust after the first inning, when the helicopter landed on the infield dirt near second base, and Paige assumed a seat in a rocking chair by his team’s dugout.4 The experience resulted in Paige concluding, “Veeck better think up something new, cause I ain’t gonna ride in no more of them things.”5 Although he did not appear in the first game, it was not long until he did see action and start contributing to his team’s success.

His first appearance was on April 22, the sixth game of the season, and he needed a wakeup call. He came in to relieve in the seventh inning of the second game of a doubleheader. The first game had gone 18 innings and more than seven hours had elapsed, leaving very few of the announced crowd of 3,486 around to see Paige. His wild pitch advanced runners to second and third, but then he bore down and got the game’s final batter Mel Nelson to hit a comebacker for the final out.6 The 3–2 win broke a string of four losses for the Marlins.

After three successful relief appearances, including two saves, he had his first start of the season on April 29. Against the Montreal Royals, in front of a crowd of 5,536, the largest since Opening Day, he pitched a seven-inning complete game shutout in the second game of a doubleheader for his first win of the season, allowing only four singles. He threw only 83 pitches, but was not allowed to use his hesitation pitch.7 Subsequently, league President Frank Shaughnessy ruled that Paige could throw the pitch in the International League. The complete game was the first of the season by a Marlins pitcher.

He was pitching mostly out of the bullpen and sometimes in bad luck. On May 26, he entered the game in the seventh inning after three Miami hurlers had not been able to solve the bats in the Richmond lineup. As noted by Shelley Rolfe in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “They laughed when Ol’ Satch shuffled to the mound but after a while the (Richmond) Vees and the crowd discovered Paige was no laughing matter. It wasn’t that the Vees failed to threaten Satch, it was just that Paige knew what to do every time they did, and he did it in his own good time.”8 The game went into the 13th inning. Paige struck out eight batters in his seven innings of work, but Richmond pushed across a run in the bottom of the 13th for the win, bringing Paige’s record to 1–2 with three saves.

A big crowd of 6,895 came to the Miami ballpark on Memorial Day and got a double-dose of Satchel. In the first game, he entered the game with two outs in the fifth inning and allowed neither a hit nor a run over the balance of the seven-inning game for his second win. In the second game, he recorded the final out for his fourth save of the season.

Signed on initially to help the attendance figures, Paige was quickly becoming the pre-eminent reliever in the league. On June 24, in the second game of a doubleheader against Toronto he played the stopper role. The Maple Leafs had started the series in Miami by defeating the Marlins 13–1 and 12–0, and Miami starter Frank Snyder had yielded three runs in the first inning. Paige came into the game with two outs and went the rest of the way. The Marlins came from behind to win, Paige’s record stood at 5–2 with seven saves, and the Marlins were four games above .500. His ERA stood at 1.50, and he even had contributed with a single in three at-bats on June 24.9

Veeck was always quick with a promotion to spur attendance, and on July 11, old age was on the program as the ageless Satchel (four days past his 50th birthday), was matched up against Connie Marrero, the 45-year-old former Washington hurler, now pitching with Havana. Close to 6,000 spectators looked on as Paige pitched the first six innings, striking out eight, and Miami won, 1–0, for Satchel’s sixth win of the season.

Top-flight entertainment in the form of Clay Poe’s Greater Miami Goodwill party brought a record 11,836 through the turnstiles three days later. The Vagabonds, Dagmar, Micki Marlo, and Pat Manville took center stage during the 45-minute extravaganza.

Satchel was thriving in the warm weather of Miami and pitched his best ball on Sunday afternoons, capturing six of his first eight wins on Sundays. After being sidelined by a bad cold in the early part of July, he made sure that on subsequent trips to the northern stretches of the International League, he would be prepared. He would wear four sweatshirts and a rubber shirt beneath his uniform. “I’m never going to be cold again when I pitch in Buffalo, Toronto, or Montreal.”10

The Marlins were in first place for a brief moment on July 29, after Satchel hurled six scoreless innings in relief as his team won 5–4 in 13 innings against Montreal, but hit a tough stretch in August.

On August 7, the Marlins moved their show to the Orange Bowl and packed in an all-time minor league record 57,713 fans to witness Paige’s fourth start of the season. Paige not only was the pitching star that night, but his long double to deep left-center field scored three runs as Miami defeated Columbus 6–2. Proceeds from the contest, which featured four bands in an entertainment extravaganza, went to charity.11 Satchel struck out five batters and scattered seven hits in 72⁄3 innings of work for his ninth win of the season. Having lost five straight, Miami was in danger of dropping out of contention before Paige stopped the losing streak.

Paige’s finest performance came on the evening of August 13 when he defeated Rochester, yielding but one hit for his tenth win of the season. He struck out three batters and walked none in his seven-inning masterpiece. The only hit of the game was a fourth-inning single off the bat of Tommy Burgess. In his first 31 games, Paige was 10–3 with 10 saves and had a 1.50 ERA. In 90 innings, he had struck out 64 and walked only 20.

His longest outing of the season came on August 19 against Buffalo. He started but was not very effective, yielding three runs over the first six innings. But he was able to put his team up 5-3 with a two-run double in the bottom of the sixth. After the sixth inning, there was a two hour and eleven minute rain delay, but Satch remained in the game, lasting 82⁄3 innings as the Marlins won 5–4.12

Satchel led his team in appearances with 37 as they finished third in the league with an 80–71 record. In games in which Paige appeared, the Marlins were 27–10. The third-place finish earned the Marlins a place in the playoffs against Rochester. Down two games to none, the Marlins staged a come-from-behind rally to win the third game of the playoffs. Paige set the side down in order in the eighth inning and was credited with the win. Miami lost the series to Rochester in five games.

When 1957 rolled around, Satch showed up for spring training in Stuart, Florida, ready to go. On arrival, he said, “I’ve already contacted my Indian friend who makes my special snake oil. And I hear Stuart is a fine place for spring training…good fishing, I mean.”13 It was still 1957 and still very much the Jim Crow South. When he showed up, he was informed that the Marlins were a bit short-handed in the pitching department and he might need to be used as a starter on Opening Day. His response was vintage Paige. “I’ll be ready to pitch if I don’t have any miseries between now and then. So don’t you go running me and getting my feet tired.”14

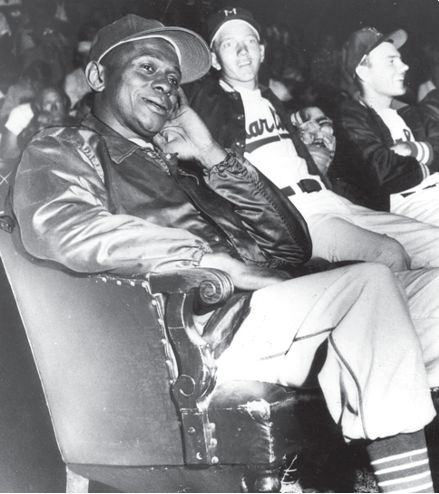

Satchel Paige would spend three seasons with Miami. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

One year in Miami was enough for Veeck and he arranged the sale of the team to Miami media mogul George Storer prior to the 1957 season. Showmanship was still on the agenda for the April 17 opener against Toronto, courtesy of impresario Ernie Seiler. Entertainment was provided by, among others, Preacher Rollo and his Dixieland Saints, and during the National Anthem, bombs burst in air as fireworks illuminated the sky beyond the left-field fence. And then the teams took to the field and engaged in a marathon that lasted well into the night before being halted at 12:50AM by curfew. After 16 innings and four hours and 49 minutes, the score was tied 3–3.15

Paige did not pitch in the opener, but he had developed a new pitch for his noted arsenal. He called it the Hum Bug Pitch. “It hums and makes the batters buggy. It has nothing to do with my dipsy-doodle pitch, my hesitation pitch, or any of the others.”16

A well-rested Paige pitched for the first time on April 28 in the second game of a Sunday doubleheader. He went the entire seven innings, scattering six hits and striking out nine as Miami defeated Buffalo and Luke Easter, 7–1. The Marlins were in first place and would stay there through the first two weeks of May. Then the wheels fell off. The team’s bats went to sleep and each of the pitchers suffered. By June 18, Satch’s record stood at 3–3. In his three losses, he had allowed only eight runs in 22 innings, losing by scores of 2–0, 3–0, and 3–2. The team had fallen to seventh place and was 10 games below .500.

By the time Satch’s 51st birthday rolled around, the team had risen to sixth place and they were playing in Columbus. It was the fifth inning on July 7 and the Marlins were clinging to a one run lead. Starting pitcher Earl Hunsinger was tired and reliever Dick Bunker had been ineffective. In strolled Paige and he went the rest of the way to record his fifth win of the season.

The team could not establish anything in the way of momentum and during the last week of August, the bats went into the deep freeze again, and once more Satch was the victim of shutout pitching. On August 29, he was on the short end as the Marlins lost to Columbus 3-0. He went all seven innings in the first game of a doubleheader only to be shut out for the fourth time in his eight losses. His record stood at 8–8 with six saves.

On Labor Day, games were scheduled for both morning and afternoon and Paige took to the mound in the opener. In the bottom of the fifth, Miami scored three runs but nobody was really noticing. By then 15 Havana batters had come up, and 15 Havana batters had been retired. Satchel had a perfecto going and he kept it going until the eighth inning when with two outs, Elio Chacón singled for the first Havana hit. Paige went the whole nine innings, giving up three hits while striking out eight for the 3–0 win, his ninth of the season.

The Marlins went into the last week of the season challenging for a playoff spot. They won 10 of their last 14 games, including two wins by Paige to edge out Rochester for a playoff berth. In the playoffs, the Marlins won the first round, defeating Toronto in six games, but fell to Buffalo in five games for the league championship. Against Buffalo, Paige pitched seven innings in the opener, losing 2–0, and in the finale, he lost 7–1.

Nevertheless, it was another good season for Paige who went 10–8 during the regular season with a 2.42 ERA in 119 innings.

Early in the 1958 season, Paige was on the wrong side of the law when he was arrested and convicted for speeding and having an improper driver’s license. Satch found the judge, Charles H. Snowden, to be a fan. The Judge deferred the 20-day jail sentence until after the season, and put forth some criteria that could lessen the sentence. Paige would receive one day off for each win, be credited for one day off for each run scored, and be credited for one day off for each time he struck out Luke Easter.17

That season, the Marlins got off to a bad start, losing 18 of their first 27 games before putting together a seven-game winning streak. Paige tossed a three-hitter against Columbus to win the final game of the run.

However, Satch was losing more than he was winning in the early going. Through June 8, he was only 3–4 with two saves and the way he was going, it looked as though he would be the guest of the City of Miami at season’s end. The team was not doing well either. At the close of business on June 11, they were in seventh place, nine games behind the league leaders, and Paige found himself on the disabled list. He missed 14 of his team’s games but came back to win his fourth decision of the season, defeating Montreal 4–1.

As June turned into July, the Marlins made their way toward the first division and Paige saw more action. He made seven appearances between June 29 and July 13, going 4–1 with one save as the Marlins climbed over .500. On July 10, he entered a game with two on and one out in the eighth inning. He recorded the final five outs to save a 5–2 win over Havana.

As good as Satchel was on the field, his off-the-field behavior was irking management. He missed flights and was unreliable in terms of showing up for work. On July 27, he had shut out Toronto 3–0, in a nine inning complete game. But less than ten days later, things took a turn for the worse as Paige feuded with management, mostly over money. The pitcher was suspended indefinitely on August 5. At the time, his record was 9–7 with three saves and an ERA of 3.09.18 Indefinitely was 12 days. He came back to defeat Buffalo 6–1 for his 10th win, but the Marlins were left fighting for the last playoff spot going into the last two weeks of the season.

Sometimes, one’s reputation can cause problems and such was the case late in the season when the Marlins were flying back to Miami from Havana at the end of August. Satchel showed up 15 minutes before takeoff only to find out that his seat had been sold to someone else, the airline thinking he would be a no-show. He went back on a later flight.19

On September 1, Miami played the first of a four game set against Columbus. They needed to sweep Columbus and Havana in their last seven games to move past Columbus in the standings for the final playoff spot. Paige started for Miami against Columbus and allowed only two runs, but his teammates were unable to score and there would be no more starts for Satchel Paige. He pitched a scoreless inning in relief in his team’s finale on September 6 to end the season with a 10–10 record and a 3.04 ERA.

He didn’t quite get the credit he needed to stay out of jail for the preseason traffic violation, but the judge was in a forgiving mood and gave Satch credit for effort.20

At season’s end, Paige hung up his spikes, and it was made official when he was released by the Marlins in April 1959. Although there would be barnstorming and brief appearances, often as publicity stunts, over the next several years, including a five-game stint with Portland of the Pacific Coast League in 1961 and his last major-league appearance with Kansas City in 1965, it was over. As Satchel said, “I’m not runnin’ out of baseball. It’s just that mabba baseball is runnin’ out of Satchel.”21

ALAN COHEN is a retired insurance underwriter who has been a member of SABR since 2011. He has written more than 30 biographies for SABR’s BioProject, and has contributed to 13 SABR books. He serves as Vice President-Treasurer of SABR’s Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter and contributed to the chapter’s recently published “100: The 100 Year Journey of a Baseball Journeyman—Mike Sandlock.” His first game story, “Baseball’s Longest Day – May 31, 1964,” has been followed by several others. His ongoing research into the Hearst Sandlot Classic (1946–1965), an annual youth All-Star game which launched the careers of 88 major-league players, first appeared in the Fall 2013 Baseball Research Journal, and has been followed with a poster presentation at the SABR Convention in Chicago. He serves as the datacaster (stringer) for the Hartford Yard Goats of the Class-AA Eastern League. A native of Long Island, he now resides in West Hartford, Connecticut, with his wife Frances, two cats and two dogs.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the endnotes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and the following:

Fraley, Oscar. “Ageless Satchel Paige Called ‘Most Wondrous Performer,’” Panama City Herald, August 15, 1956:10

Paige, Satchel with David Lipman. Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (New York, Grove Press, 1961).

Notes

1. Oscar Fraley, Panama City News, November 14, 1956, 8.

2. Saves were not an official statistic at the time. Total based on author’s calculations.

3. Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck as in Wreck (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1962):311.

4. Jimmy Burns, “8,806 at Marlins’ Game See Fireworks and Delivery of Satchmo by Helicopter,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1956:27.

5. Oscar Ruhl. “88-year battery—Satch and McCullough,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1956:15.

6. George Beahon, “Wings Top Miami, 10–6, In 18 Innings, Then Lose,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 23, 1956:18. (The Sporting News recorded a passed ball rather than wild pitch.)

7. “Ol’ Satch Hurls Miami to 3–0 Shutout Victory,” Boston Traveler, April 30, 1956:24.

8. Shelley Rolfe, Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 27, 1956:B1.

9. Burns, “Satch Aging, He has 1.50 ERA and He’s Still Hittin’,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1956:30.

10.. Burns, “Satch Miami’s Sunday Ace—Enjoys Afternoon Work,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1956:28.

11. Burns, “Marlins Set 57,713 Gate High at Orange Bowl Show,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1956:17.

12. Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 20, 1956:19.

13. Burns, “Satchel Checks on Snake Oil, He’s all Set for Spring Drills,” The Sporting News, March 13, 1957:36.

14. Burns, “Miami Marlins All Smiles—Satchel Paige Shows Up,” The Sporting News, April 3, 1957:31.

15. Burns, “Seiler Whips Up ‘Spectacular’ at Marlin Opener,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1957:27.

16. The Sporting News, April 24, 1957:27.

17. “Satch Can Pitch Himself out of Jam,” Fort Pierce News-Tribune, April 24, 1958: 1.

18. Burns, “Paige Suspended by Miami to Climax a Hectic Interlude,” The Sporting News, August 13, 1958:36.

19. Burns, The Sporting News, September 3, 1958:32.

20. The Sporting News, January 7, 1959:27.

21. “Legendary Satch Turns to Movies,” Fort Pierce News-Tribune, September 30, 1958:5.