Scoring Every Inning

This article was written by Robert E. Jones

This article was published in 1981 Baseball Research Journal

The structure of baseball provides rare performances that can secure any game’s place in baseball history. No one will forget having seen a no-hit game (or a perfect game!), a high strikeout game, or a batter going 6 for 6 or hitting four home runs. Nor will it be forgotten who made these singular achievements. But there is a team feat, scoring in every inning, which is probably the most unusual occurrence in baseball, and is probably the least appreciated of baseball’s rarities. It is unusual because of the incredible combinations of team play needed to pull it off, and it is less appreciated because no heroic efforts are required of any one player. The only result of the game is an interesting line score.

Consider that most of baseball’s rules operate to prevent runs from being scored. The offensive team does not control the ball. Most of the time, the game is played by nine players against one, and at best nine against four. Of the nine offensive opportunities a team has, scoring in only one of them is often sufficient to win a game. In the majority of games, the winning team scores in only two or three of their allotted times at bat.

Since 1900, only two teams have managed to score in each of nine innings of a game. On June 1, 1923, the New York Giants did it against the Philadelphia Phillies, winning 22-8. On September 13, 1964, the St. Louis Cardinals beat the Chicago Cubs 15-2 and likewise never gave the opposing pitchers an inning to be proud of.

How did the Giants and Cardinals manage their scoring binges? Simple. They had a day when hitters could do no wrong, opposing pitchers could do no right, and a more than moderate amount of luck was thrown in. Let’s look at these games in detail, starting with the New York-Philadelphia game in 1923.

The Giants entered Baker Bowl in Philadelphia on June 1 solidly in first place, 5½ games ahead of Pittsburgh and 17½ games ahead of the day’s opponent.

New York scored quickly in the first. Dave Bancroft and Heinie Groh both singled. After Frankie Frisch flied out, Irish Meusel walked to set up Ross Youngs’ bases-clearing triple to right-center. Walter Holke dropped George Kelly’s fly to short right, scoring Youngs.

In the second, Bancroft hit a one-out single to left and scored on Groh’s double to right-center. Following an out, Groh went to third on a passed ball. Meusel walked and Groh scored on Youngs’ single.

The Giants scored only one run in both the third and fourth innings. In the third, walks to Jimmy O’Connell and Claude Jonnard, who had replaced Rosie Ryan on the mound, were followed by Groh’s two-out single to score O’Connell. O’Connell’s solo home run, the only homer of the game, put across the Giants’ run in the fourth.

After four innings, the game was still close, 8-6 in favor of New York. The next two innings saw the Giants pull away for good, sending nine batters to the plate each inning and scoring five runs each time. Bancroft opened the fifth with a walk and Groh was safe on Russ Wrightstone’s error. Then, Frisch doubled, scoring Bancroft and Groh, and Meusel singled, scoring Frisch. Youngs singled, and one out later O’Connell doubled, scoring Meusel. Youngs stopped at third, to score on Earl Smith’s infield out.

Bancroft, Groh, and Frisch led off the sixth with consecutive singles. Meusel’s out was only a breather. Youngs doubled, scoring Bancroft and Groh. Kelly singled, scoring Frisch. O’Connell doubled, with Kelly stopping at third. Heinie Sand’s error on Smith’s grounder allowed Kelly to score with the fifth run.

With the score 18-7 after six innings, the only matter to settle was whether the Giants could continue their magic. Groh punched a one-out single in the seventh, and was forced by Frisch. Freddie Maguire ran for Frisch. Following Meusel’s third free pass of the game, Maguire scored on Youngs’ single.

In the eighth, O’Connell led off with a single. Alex Gaston, who had taken over for Smith behind the plate, walked. Jonnard sacrificed both runners along, and O’Connell scored on Wrightstone’s second error of the day. Gaston moved to third on the error and scored when O’Connell was forced at second.

It looked like the scoring streak would end in the ninth when Maguire and Bill Cunningham, playing for Meusel, both made quick outs. But Youngs tripled and Kelly’s double to left-center scored him to set the record.

The Giants were clearly in offensive control that day, sending 63 men to the plate. Three batters: Groh, Youngs, and O’Connell, had five hits; and Youngs had seven RBIs. O’Connell’s five hits included three doubles and one home run. Only once, in the ninth, did the first run of the inning score with two out. Only once, in the eighth, did the first run score by the aid of an error.

Click here to view the box score of this high-scoring game at Baseball-Reference.com.

Forty-one years later, the St. Louis Cardinals matched the Giants inning for inning in cozy Wrigley Field.

Curt Flood led off the Cardinal first with a single. After Lou Brock struck out, Dick Groat singled, Flood taking third. Ken Boyer’s infield hit scored Flood, and Groat took third on Cub pitcher Dick Ellsworth’s error. Groat scored on Bill White’s grounder to second.

The Cardinal run in the second inning scored on Julian Javier’s lead-off home run.

In the third inning, Groat led off with a single to center and was joined on base by Boyer, who drew a walk. White sacrificed, but all runners were safe when a force play failed. Mike Shannon then singled, driving in Groat and Boyer.

Lou Brock, blossoming with the Cardinals after having been acquired from the Cubs earlier in the season, opened the scoring in the fourth inning with a lead-off home run. Two outs later, Boyer was safe on Joe Amalfitano’s error, taking second on the play. Boyer scored on an error by Andre Rogers off White’s bat.

With one out in the fifth, Bob Uecker stroked a single to left, his only hit of the day. Curt Simmons, the Cardinal pitcher, who was breezing along with a 7-I lead, bunted Ijecker to second but was safe himself on Don Elston’s error. Flood sacrificed Uecker and Simmons to third and second respectively. Groat singled, scoring Uecker, and Simmons continued home on Amalfitano’s second error of the day.

Shannon’s solo home run with one out in the sixth kept the Cardinal scoring string alive.

In the seventh, with Sterling Slaughter pitching for the Cubs, the top of the potent Cardinal batting order struck again. In quick succession, Flood singled, Brock doubled, and Groat doubled, scoring Flood and Brock. Dal Maxvill, running for Groat, scored on Boyer’s single. That was all for Slaughter, but that was all for St. Louis, too, as John Flavin took over on the mound and retired the side.

Javier hit a lead-off double in the eighth inning and advanced to third on Simmons’ grounder to Ron Campbell, who had replaced Amalfitano at second. Flood singled Javier home to set up the history-making ninth inning.

With one out in the ninth, Boyer was safe on Campbell’s error. White singled Boyer to third, and Shannon scored Boyer with a sacrifice fly.

The key to the Cardinal’s success was making the most of the opportunities they had. Each player, except Ray Washburn, who did not bat, scored, knocked in a run, or kept a rally alive for a subsequent run. Cardinal players reached base 25 times. All except two, Uecker in the third (walk) and Javier in the sixth (double), figured in the scoring.

Both New York in 1923 and St. Louis in 1964 went on to win pennants, the Giants in a laughter, and St. Louis with the help of the famous Philadelphia collapse. Both teams beat the New York Yankees in the World Series, the Giants in six games and the Cardinals in seven.

Here is the St. Louis-Chicago box score of September 13, 1964, at Baseball-Reference.com.

ADDENDUM

On the Probability Of Scoring Every Inning

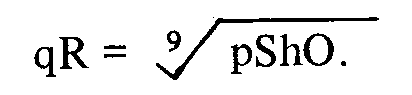

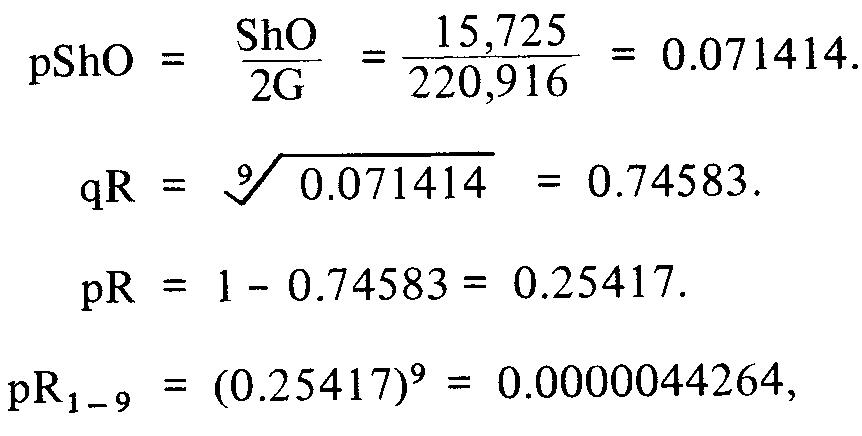

The way to find the probability of scoring in nine consecutive innings is to find the probability of scoring in one inning (pR) and raise that to the ninth power. Trying to find pR directly is difficult, since there are so many ways of scoring a run. The most useful method is to find the probability of not scoring in an inning (qR), from which pR can be easily found:

pR = 1 – qR

In a shutout game, a team does not score in any inning. Therefore,

pShO = (qR)9

and

In 110,098 regular season games from 1901 through 1980, 15,725 shutouts have been thrown.

or once every 225,917 games. It is assumed that the instances of extra-inning games balance rain-shortened games so each game can be considered to last nine innings.

Practically speaking, only the visiting team can score in each of nine innings. If the home team scores in the first eight innings, it should be so far ahead that the game would end after the visitors’ last turn at bat. Though there are two chances for a shutout game in each game, there is only one chance for a nine-inning scoring spree, making an expected occurrence of once every 451,834 games.