Setting the Record Straight on Major League Team Nicknames

This article was written by Ed Coen

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

Of the major league teams that trace their history before 1960, most started out with several short-term unofficial nicknames or even no nickname at all. Although several reputable sources provide a history of these nicknames, there are numerous contradictions between the available sources, and sometimes even when these sources agree, they conflict with the original sources. In other words, they do not reflect what the team was actually known as at the time. The purpose of this study is to identify the nicknames, based on contemporary newspapers, that each existing team has been known as throughout its history. This article can then be used a reference to avoid such discrepancies in the future.

The Need for This Study

To illustrate the need for such a source, I examined two of the most reliable sources to which researchers often turn. David Nemec’s The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball – Second Edition is a useful book for that period in baseball history and provides a nickname for each major league team in each year from 1876 through 1900 as well as National Association teams from 1871-1875.1 The teams page on Baseball-Reference.com is another popular source for nicknames by year for each team from 1871 to the present.2 Two other sources deserving mention are Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Franchises, by Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella and Baseball Team Names: A Worldwide Dictionary, 1869-2011.3,4 Total Ballclubs provides a history of all current and former major league teams, including a list of nicknames used, but does not provide a detailed description of what names were used in what year. Baseball Team Names provides a wealth of information about the origin of official, unofficial, and alternate names of various teams throughout the world, but since it does not consider frequency of use, it is not germane to this study.

Nemec and Baseball-Reference.com agree that the Boston National League team was known as the Beaneaters from 1883 to 1900. But would the fans in Boston have referred to their favorite team as the Beaneaters? An electronic search of “beaneaters” or “bean eaters” in the Boston Globe during the 1883 baseball season yielded one hit, and that one was a dispatch from New York, likely written by a New Yorker. A similar search for the 1891 National League championship season in both the Boston Globe and the Boston Post yielded five hits for the Globe and none at all for the Post. Of these five, two were in headlines, indicating that they were likely not written by a sportswriter, but by someone less familiar with the team. One was a direct quotation from Cap Anson, manager of the rival Chicago Colts. One was referring to Boston’s American Association team. The final quotation was in a column in which a writer surveyed various quotations heard from the crowd. A manual search of the other Boston papers found no mention of Beaneaters in this time period. Beaneaters was not a nickname for a specific team, but a nickname for someone from Boston used by outsiders. This is illustrated by the fact that Boston’s Union Association, Players League, American Association, and American League teams were also occasionally called the Beaneaters by reporters from other cities. Other similar examples are the New York Gothams and the Philadelphia Quakers. These nicknames are found in multiple modern sources, but they do not represent what the teams were known as at the time they played. Although it sounds strange to a modern ear to hear a team called simply the “Bostons,” that is exactly how the Boston National League club was most commonly known to its own fans from 1878 through 1900.

Another example in which both sources agree is the St. Louis National League club in 1899. They all say the team was known as the Perfectos. But how often did the St. Louis writers use that moniker? In a search of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the St. Louis Globe Democrat, of the 38 hits, 11 were unrelated to the St. Louis baseball team. Of the remaining 27, four were in headlines, which were not necessarily written by sportswriters, and eight were either in descriptions of road games, often written by out-of-town reporters, or direct quotations from a paper outside of St. Louis. This leave 15 hits or approximately 1 per month per paper. Of these 15, most were either a list of upcoming games or a short discussion of various facets of the team. Only one hit, out of two newspapers’ coverage of 87 home games, was in an account of a home game. A manual search of the St. Louis Star yielded similar results. Although this strictly conforms to Nemec’s stated criterion of “the nickname, if any, that was used most often in our primary sources,” it again appears that by far the most common way to identify the team was no nickname at all.5 Nemec also uses Perfectos as the nickname for the 1900 team, while Baseball-Reference.com and a look at the all of the St. Louis papers show that they were regularly called the Cardinals then.

Others have previously raised the issue of modern sources not conforming to original sources. In the 1998 Baseball Research Journal, Marc Okkonen used his experience poring through newspapers to compile a list of the common nicknames used by teams from 1900 through 1910.6 Although I disagree with him on a few things, this current study is essentially an expansion of Okkonen’s work to include the entire history of all current teams.7 In articles in the 2003 and 2006 National Pastime, Bill Nowlin provided enough information on the nickname of the club now known as the Boston Red Sox to allow Baseball-Reference.com to correct its entry for that team.8, 9 This study aims to correct the record for all teams and all years.

Definition of the Terms

Although in most contexts, the word “nickname” implies something informal, the general practice with sports teams is to use “nickname” whether it’s official or not. For the purpose of this study, “nickname” refers to the identifier other than the city for any team.

In this study I refer to “official” and “accepted” nicknames. An official nickname is a nickname given by the club itself. In some cases, the name is part of the club’s corporate name, or an official statement was made from the club’s front office. In others, the recognition was tacit, such as the use of the name on the team’s uniform or in official publications. An accepted nickname, on the other hand, is an unofficial nickname made up by the fans or the press that has become widespread. In this study, I define an accepted nickname as any of two or three nicknames that were regularly used in at least two local newspapers in accounts of home games.

As for the definition of “regularly,” that is where subjectivity comes in. Since it is not practical to count all mentions of a name for an entire season for all newspapers in a given city, I looked through the accounts of several home games for several different homestands throughout the season. If I found more than about three or four mentions, I considered it a regularly used nickname in that paper. A typical sample size was about ten games, but when it was not obvious if a name was regularly used, I looked at more games until satisfactorily determining that a nickname was accepted. As a general rule of thumb, if a nickname was used in more than a third of the home game accounts in a newspaper, I considered it regularly used in that paper. Although this method is admittedly subjective, in the majority of cases it was obvious one way or the other. In general, most papers tended to pick a name and stick with it throughout the season. If any two papers in a team’s city were deemed to use a certain name regularly, as defined by this process, it was considered an accepted nickname.

In many cases an unofficial accepted nickname evolved into an official nickname. No attempt was made in this study to determine the exact date of that transition.

Ground Rules

The first rule is that I relied only on contemporary local sources, primarily newspapers. As described above, sources written after the fact tend to be unreliable. When nicknames are unofficial, newspapers in other cities tend to lag behind the hometown newspapers. Since the foremost authorities on the nickname of a given city’s team are the people in that city at that time, I relied solely on several newspapers from the team’s home town. Furthermore, I only looked at accounts of home games, since accounts of road games were often written by local writers who sold them to the papers in the road team’s city. Finally, only the text of the article was considered, since headlines are often written by people such as copy editors, who might be less familiar with the team or more prone to hyperbole.

The second rule is that official names take priority. Once an official name has been discerned, no attempt is made to search for an accepted nickname. One example of the application of this rule is the 1905 to 1956 Washington Nationals. For the latter part of that period, Senators was used at least as often as Nationals, but since the team has declared itself the Nationals, I call them the Nationals. Likewise, the Oakland A’s of the 1970s were hardly ever called the Athletics, but that was still their official nickname.

The third rule is that no attempt was made to force one and only one accepted nickname on a team. Some teams simply had no nicknames. The above example of the Boston National League club in the nineteenth century is an application of this rule. Once Red Stockings and Reds fell out of use, they are identified simply as the Bostons, since in general teams with no accepted nickname were identified by the city. On the other hand, the New York American League club from 1906 through 1912 was called the Yankees and the Highlanders almost equally. To choose one over the other would be arbitrary. They were both accepted nicknames. It would not be wrong to refer to them as the New York Yankees or the New York Highlanders.

Origin and Types of Nicknames

The first team names were simply the names of the group that sponsored the team. The Philadelphia Athletic Club became the Athletics. The Atlantic Base Ball Club of Brooklyn became the Atlantics. This style of nickname still exists today in the Oakland Athletics and the New York Mets. In the 1870s and 1880s, the team name (e.g., Atlantic, Athletic) generally appeared in standings and box scores instead of the city (e.g., Brooklyn, Philadelphia).

Another common source of nicknames was the color of the uniform. In early uniforms, it was the color of the socks that identified the team. Thus, in the 1870s nicknames included the Chicago White Stockings, the Boston Red Stockings, and the St. Louis Brown Stockings, often shortened to Whites, Reds, and Browns. This pattern continues today in the Boston Red Sox, the Chicago White Sox, the Cincinnati Reds, and the St. Louis Cardinals (originally named after the color, not the bird).

In the nineteenth century, it was also common for teams to have no nickname at all and to be identified by city name only. Newspapers of that era are full of accounts of the Bostons, the Chicagos, and the Brooklyns. Newspapers in cities with two teams tended to identify one by the city and one by another name. Philadelphia had the Philadelphias and the Athletics. New York had the New Yorks and the Metropolitans. Philadelphias, because of its length, was often shortened to Phillies. What is now the team nickname started out as just shorthand for the city name.

Nicknames in the 1890s and early 1900s were often inventions of sportswriters that caught on with the public. The club itself had little part in it. Some nicknames, such as the Brooklyn Dodgers, arose gradually, while others, such as the Chicago Colts arose suddenly. If it arose gradually, I give a year that the nickname became accepted by my methodology, but it is a judgment call. If it came about suddenly, I identify it as such.

In the 1910s official nicknames became more common. In these cases, an exact year, and sometimes even an exact date, can be discerned. Washington was ahead of their time in 1905 when they likely became the first major league team to hold a contest to determine a new team nickname: the Nationals.

By 1915 each team had the nickname it carried into the 1950s, although Brooklyn had three accepted nicknames, Dodgers, Robins, and Superbas. The latter two dropped out of use over the next 17 years. Three National League teams subsequently changed their name, only to change it back. The Braves became the Bees, Phillies was shortened to Phils and Reds was lengthened to Redlegs for short times in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s respectively.

Results

Since nicknames have been stable since 1961, the teams that began in 1961 or later are not included in this study. The only nickname changes after 1961, other than as a result of a move, were on December 1, 1964, when the Houston Colt .45s became the Astros and on November 8, 2007, when the Tampa Bay Devil Rays became the Rays.10, 11 Below, in alphabetical order of the city they occupied in the 1903–52 era, National League first, are the complete histories of each pre-expansion era team’s nickname.

National League

Boston12

When Harry Wright brought the nucleus of his Cincinnati Red Stockings to Boston in 1871, the obvious choice for a nickname was the Red Stockings. This name was accepted through 1874. In 1875, Reds was in use as often as Red Stockings, so both were accepted. In 1876, Red Stockings fell out of use, so Reds was the only accepted nickname. From 1877 through 1900 they had no nickname; they were simply the Bostons. As discussed above, the name Beaneaters was hardly ever used locally and was more of a nickname for the city than the team.

From 1901 to 1907 they were called the Boston Nationals to distinguish them from the Boston Americans. At that time, referring to a National League team as the Nationals or an American League team as the Americans was common, so every National League team was sometimes called the Nationals. Because this practice was much more common in Boston than elsewhere, Nationals is considered an accepted nickname for the Boston club. In 1907, newspapers began calling them the Doves, after owners John and George Dovey. Both Nationals and Doves appeared in multiple papers, making them both accepted nicknames. In 1908, Doves emerged as the single accepted nickname. When John Dovey sold his share of the team in December of 1910, George having died the previous year, the name Doves became obsolete.

In 1911, the Boston media tried to come up with a name based on the new owner, William Hepburn Russell. Heps, Hapes, Hopes, and Rustlers were all used, but none stands out as an accepted nickname. For 1911 then, they had no accepted nickname. This lasted only one year as Russell died in November of 1911.

Then James Gaffney bought the team and hired John Montgomery Ward as the president. On December 20, 1911, Ward suggested to reporters that the club be known as the Braves and the newspapers obliged.13 This name was an allusion to Gaffney’s involvement in New York’s Tammany Hall political machine. The organization was symbolized by an Indian, and its lower ranking members were called braves. Although the Braves started out well—the 1914 Braves staged one of the greatest late-season comebacks in history—the 1920s and ’30s were a time of futility for a city that until then was used to winning. In an attempt to reverse the Braves’ losing habit, the team had a contest to choose a new nickname. On January 30, 1936, the name Bees was chosen.14 Unfortunately, the Bees were no more successful than the Braves. A new syndicate bought the team prior to the 1941 season and on April 29, 1941, just a couple of weeks into the season, announced that they would henceforth be the Braves again.15 This name has continued in Boston, Milwaukee, and Atlanta to this day.

Brooklyn16

When Brooklyn entered the American Association in 1884, they had no nickname. This continued until 1888, when several of the Brooklyn players got married within a short span of time. Writers began to call the team the Bridegrooms, but not often enough to be an accepted nickname. The pennant winning teams of 1889 (their last year in the AA) and 1890 (their first year in the NL) were called the Bridegrooms on a regular basis. In 1891 however, the name died out and Brooklyn was left without a nickname. In 1895 through 1898 they were called the Grooms, a shortened form of the previous nickname. The name Trolley Dodgers, an allusion to the large number of trolleys that had to be dodged in Brooklyn, first appeared about this time. It was only used a few times, so it is not considered accepted.

In 1899 when Ned Hanlon took over the managerial helm, a new nickname was born. During the 1890s, a well-known show called “Superba,” known for its groundbreaking special effects, had been produced by the Hanlon brothers, no close relation to Ned.17 The show was commonly known as Hanlon’s Superba, making the Superbas a natural nickname for Ned Hanlon’s Brooklyn club. Superbas continued as the sole accepted nickname through 1909, even though Hanlon himself left after the 1905 season.

In 1910, the use of Dodgers increased enough to make it a second accepted nickname. In 1914, they hired Wilbert Robinson as their manager and in 1916, Robins joined Dodgers and Superbas as accepted nicknames. From 1916 through 1920, Brooklyn used these names, the only time any team had three accepted nicknames. In 1921, Superbas ceased to be used enough to be considered accepted, although the Brooklyn Eagle continued to use it until 1925. They continued to be known as both the Dodgers and the Robins (and sometimes alternatively as the Flock) until January 22, 1932. On that date, management made Dodgers official .18 That name has stuck ever since, even though the team moved across the continent to Los Angeles.

Chicago19

When Chicago entered the National Association in 1874, they were the White Stockings, which was the accepted name in the NA and in the National League through 1887. In 1888 they switched to black stockings, but they were only called the Black Sox by one paper, the Chicago Tribune. In 1888 and 1889 the team was known primarily as just the Chicagos. In 1890 the core of the Chicago team left for Charlie Comiskey’s Chicago White Stockings of the Players League. Chicago manager Cap Anson signed a group of young players who due to their youth became known as the Colts. Colts continued as the accepted nickname throughout Anson’s tenure in Chicago. After the 1897 season, Anson was fired from the team after 19 years at the helm. Thus, the team became known as the Orphans in 1898. Orphans continued as the accepted nickname through 1901.

In 1902 and 1903 the Chicago newspapers used a dizzying array of nicknames. Colts, Cubs, Recruits, Remnants, Orphans, and even Microbes were all common names used by at least one newspaper. They had no accepted nickname for these two years. In 1904, the list was down to two as the papers were almost equally divided between Colts and Cubs (both referring to the relatively young team) so both were accepted nicknames. In 1905 Cubs became the single accepted nickname, used by all papers except the Chicago Tribune. The Tribune was the last holdout, preferring Zephyrs in 1905 and Spuds in 1906. By 1908, Cubs was definitely official because their uniform featured a cub holding a bat.20

Cincinnati21

When Cincinnati became a charter member of the American Association in 1882, they had no nickname. The Cincinnati papers just called them the Cincinnatis for their first five years. Then in 1887 every newspaper in Cincinnati identified the local team as the Reds. Reds was the accepted nickname both in the AA and, starting in 1890, in the NL. In the ensuing years they were sometimes called the Red Stockings, Redlegs, and even Red Sox, but Reds was by far the most common. This continued until April 9, 1953, when the official name was changed to Redlegs because “Reds” had been associated with communism.22 Redlegs was the official nickname from 1953 through 1958 and on February 11, 1959, they became the Reds again.23

New York24

When New York entered the National League in 1883, they had no nickname. They were identified as New York and the American Association club was called the Metropolitans or Mets for short. In 1884, some newspapers called 6-foot 3-inch 220-pound third baseman Roger Connor “the giant of the team.”25 Gradually the word Giants came to refer to the entire team even though a look at the roster shows that no other player was particularly large. In 1885, Giants was the common nickname in most New York papers, making it accepted. Although they abandoned New York for greener pastures in California 71 years later, they never abandoned the name Giants. At 135 years and counting, Giants is the longest continuing nickname in the major leagues.

Philadelphia26

When Philadelphia entered the National League in 1883, they had no nickname. They were just called the Philadelphias to distinguish them from the Athletics of the American Association. Philadelphias proved to be a mouthful and tough to fit in headlines, so it became Phillies. From 1886, Phillies was the most common way to identify the team and it gradually evolved into the team nickname through the 1941 season. Then on February 7, 1942, Phillies publicist Bill Phillips announced that it would be changed to Phils, apparently to avoid confusion with a cigar of the same name.27 That only lasted a year however, as the team was sold and the new owner, William Cox, did not share the same concern and on March 8, 1943, announced that the team would be the Phillies again.28

A word should be added here about what some have erroneously called an alternate nickname: The Blue Jays. From 1944 through 1949, the team used a blue jay as a symbol, but never dropped Phillies from their uniform or official publications. The intent of this change is best illustrated by the headline in the March 5, 1944, article about the change in the Philadelphia Inquirer: “Phillies Accept Blue Jays as Team Emblem.”29 The designer of the emblem is shown holding up a drawing of a blue jay with the word “Phillies” under it. Clearly, the team was never meant to be called the Blue Jays and the bird was intended to be symbol, like the white elephant for the Philadelphia Athletics.

Pittsburgh30

One of the charter members of the American Association in 1882 was the Alleghenys. They represented Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh with a population of about 80,000, half the size of Pittsburgh. North of the Ohio River and west of the Allegheny River, it became part of Pittsburgh in 1907. This team is now often referred to as the Pittsburgh Alleghenys, but during its 5-year tenure in the AA, it was rarely if ever referred to as Pittsburgh in any Pittsburgh paper. They were simply the Alleghenys with no nickname. In 1887 they moved to the National League and the newspapers were divided as to whether to identify them as Allegheny or Pittsburgh. During this period, they couldn’t even agree on how to spell Pittsburgh. The Commercial Gazette, Daily Post, and Chronicle Telegraph spelled it the current way and the Dispatch and Press spelled it without the final h. All agreed that there was no nickname, although some papers occasionally called them the Allies in headlines. In 1890, the Players League formed and placed a team in Exposition Park, just across the Allegheny River from downtown Pittsburgh, very close to the site of the current PNC Park. Although technically also in Allegheny, the Players League club was known as Pittsburgh, and the National League club was known as Allegheny in all of the papers. Some modern sources use Innocents and Infants as the nickname for the team in 1890 only, alluding to their young players, but these names were very rare in all Pittsburgh newspapers. In fact, the team was called the Alleghenys much more often on 1890 than in the previous three years.

After the Players League folded, the National League team moved to Exposition Park and became the Pittsburghs. At the same time, other cities’ newspapers began calling them the Pirates, as a derogatory nickname. This was an allusion to events that occurred after the collapse of the Players League. An agreement was made among National League and American Association clubs that all players who jumped to the Players League would return to their 1889 team. When the Athletics inadvertently left second baseman Lou Bierbauer off their reserve list and Pittsburgh claimed him, they were derisively called “pirates.” The name did not catch on at first with the Pittsburgh papers who from 1891 through 1894 just called them the Pittsburghs. In 1895 the Pittsburgh papers used Pirates enough that it can be called the accepted nickname. This continued until 1898, when as a result of the patriotic fervor sweeping the country during the Spanish American War, at least two Pittsburgh papers referred to the locals as the Patriots as often as the Pirates. The double nickname only lasted one year, and from 1899 on to the present, they remained the Pirates. Finally, in 1911 the US Postal Service added the final h which had always been in the city’s official name and all papers called them the Pittsburgh Pirates.31

St. Louis32

St. Louis was a member of the American Association for its entire existence, 1882–91. In 1882, they were called the Browns, after the color of the uniform socks. In 1883, they changed this color to red and had no nickname. In 1884, they went back to being the Browns, which continued after their 1892 move to the National League, to 1898. In 1899 they had no accepted nickname. In some accounts, they were called Patsy’s Perfectos, after Manager Patsy Tebeau. This was a reaction to Brooklyn’s new nickname, Superbas and Perfectos both being popular Cuban cigars.33 The appearance of Perfectos was too rare for it to be considered accepted. The following year they became known in all papers as the Cardinals, due to the red trim on their uniforms.

The Boston Red Sox were one of the early teams to put a team nickname (rather than city name, logo, or initial) across their jerseys. Pictured here is Jake Stahl in 1912. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, HARRIS & EWING)

American League

Boston34

From their 1901 inception through 1906, the Boston American League club was called the Boston Americans to distinguish themselves from the Boston Nationals. In 1907, both Americans and a new nickname, Pilgrims, were primary names used in several Boston newspapers, so both were accepted nicknames that year. After the season, team president John I. Taylor decided he didn’t care for the newspapers’ choices and on December 18, 1907, he announced that henceforth the team would be known as the Red Sox.35

Chicago36

In 1901 and 1902 the Chicago American League club was called the White Stockings and White Sox about equally. In 1903 White Sox took over as the single accepted nickname and by the end of the decade, use of White Stockings disappeared altogether.

Cleveland37

In 1901 the Cleveland American League club had no nickname. In 1902 they were regularly known as the Blues. In 1903 and 1904 they were known as both the Blues and the Napoleons, for their star second baseman Nap Lajoie. In 1905, Lajoie became the manager and they were exclusively the Napoleons, although it was shortened to Naps on occasion. In 1906, Naps became accepted and continued through 1914. When Lajoie left after the 1914 season, the club ownership and newspapers got together and on January 16, 1915, chose Indians, which they have retained ever since.38 This name was based on a former nickname of the old National League club, which was sometimes called the Indians in 1897 and 1898 because of outfielder Lou Sockalexis.

Detroit

Detroit’s American League entry was always known as the Tigers, although during Ty Cobb’s tenure as manager (1921 through 1926) it was sometimes spelled Tygers.39

New York40

The first two years of this franchise, they were the Baltimore Orioles.41 From 1903 to 1905, Highlanders was the accepted name, due to their location, Washington Heights in Manhattan. Yankees was used occasionally in 1904 and 1905, but not enough to be considered accepted. From 1906 through 1912 Highlanders and Yankees were both accepted. In 1913, when they abandoned American League Park and began sharing the Polo Grounds with the Giants, Highlanders almost disappeared as a nickname. Yankees has been the accepted nickname ever since.

Philadelphia

There is no question here. Whether in Philadelphia, Kansas City, or Oakland, the official nickname has always been the Athletics, although A’s, as an alternate nickname, dates back to at least 1915.42

St. Louis43

In 1901, the franchise was in Milwaukee and called the Brewers.44 In 1902 they moved to St. Louis and adopted the discarded name of the National League club: Browns. This continued through 1953, although in 1905 there was a vain attempt by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch change the name to Ravens. From the move to Baltimore for the 1954 season to the present, the team has been the Orioles.

The Washington Post’s banner headline on September 30, 1924, after the Washington Senators clinched the American League pennant. During this era, the Washington team was just as frequently known as the Nationals as it was the Senators. (Newspapers.com)

Washington45

Upon entering the American League, Washington chose the nickname from the 1892-1899 National League club: Senators. After four losing seasons, they decided to hold a fan contest to come up with a new nickname, hoping it would change their luck. On March 25, 1905, the winner was announced.46 Going back to the great Washington teams of the 1860s and 1870s and the Eastern League pennant winners in the 1880s, they chose Nationals. These Nationals were no more successful than the Senators and Senators gradually re-emerged as alternate but unofficial name. Although Senators was used more often than Nationals in the rest of the country, Nationals remained the official name through 1956 and was used often in the Washington papers. The shortened form Nats was quite common in headlines even after Senators became the official name. Long-time owner Clark Griffith stubbornly clung to Nationals because he felt that using the name Senators for a usually losing team detracted from the dignity of the United States Senate.46 When Calvin Griffith took over after the death of his father, he decided to make the preferred nickname official. On October 30, 1956, he announced that Senators would now be the official name.47 This only lasted four years, as in 1961 they became the Minnesota Twins.

ED COEN is a Senior Nuclear Engineer with Enercon Services Inc. who, in his spare time, follows the Milwaukee Brewers, reads SABR publications, and occasionally contributes to them. He has been a SABR member since 1984. His email address is edcoen82@gmail.com. His research interests include Milwaukee baseball, nineteenth century baseball, and team nicknames.

Summary

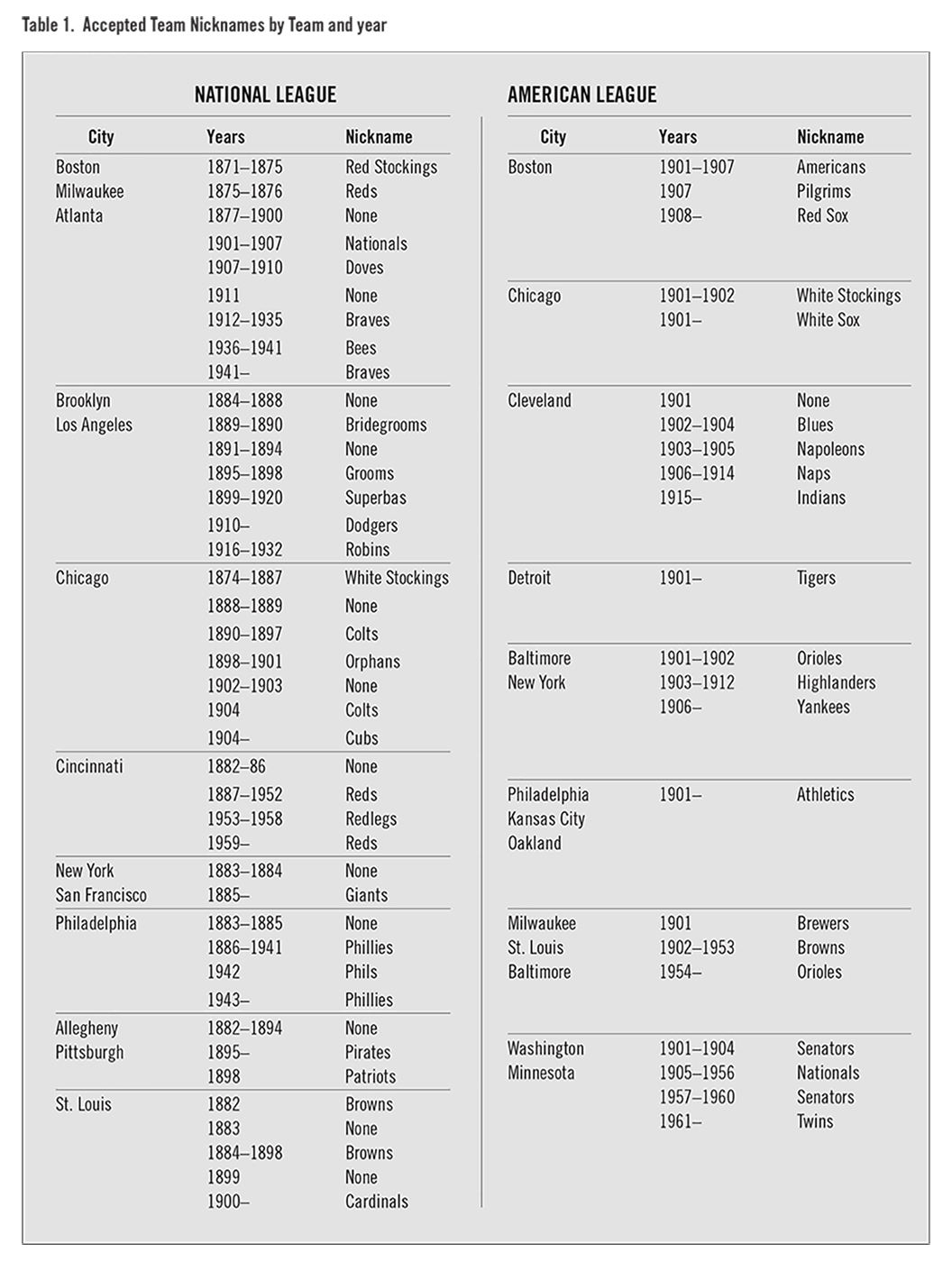

Table 1 shows the accepted nicknames used by each club by season:

(Click image to enlarge)

Notes

1 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball – Second Edition, (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2006).

2 Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.Baseball-Reference.com/teams/

3 Donald Dewey, Nicholas Acocella, Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Teams, (Toronto: Sport Media Publishing, Inc., 2005).

4 Richard Worth, Baseball Team Names: A Worldwide Dictionary, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2013).

5 Nemec, 523.

6 Marc Okkonen, “Team Nicknames,” The Baseball Research Journal 27 (1998): 37-39.

7 Okkonen dismisses Pilgrims altogether as a nickname for the Boston AL club but my research shows it was used as often as Americans in 1907 in all Boston papers except the Post so I consider both Pilgrims and Americans to be accepted for that year. Okkonen refers to the 1911 Boston NL club as the Rustlers, but since only the Globe called them that, I do not consider it an accepted nickname. Okkonen wrote that the Chicago AL club was identified as the White Stockings only in 1900 through 1902, but I found both White Stockings and White Sox to be used regularly in 1900-1902. Okkonen considers Blues to be Cleveland’s nickname in 1901, but I did not find it, or any other nickname, in any newspapers that year. Okkonen states that the press was not involved in the change of Washington’s nickname from Senators to Nationals, but it was actually a committee of sportswriters that organized the contest to come up with a new name.

8 Bill Nowlin, “The Boston Pilgrims Never Existed,” The National Pastime 23 (2003): 71-76.

9 Bill Nowlin, “About the Boston Pilgrims,” The National Pastime 26 (2006): 40.

10 Mickey Herskowitz. “Houston ‘Astros’ To Play Beneath Big Dome in ’65,” Houston Post, December 2, 1964.

11 “Time to shine: Rays introduce new name, new icon, new team colors and new uniforms,” raysbaseball.com, November 8, 2007.

12 Newspapers used in this analysis: Boston Herald (1871-1912), Boston Globe (1872-1911), Boston Post (1872-1911), Boston Journal (1871-1911), Boston Record (1907).

13 T. H. Murnane, “Found—A Name for Those South End Fence-Breakers, ‘Boston Braves,’ ” Boston Daily Globe, December 21, 1911.

14 James C. O’Leary, “Braves Are to Be Called Bees”, The Boston Globe, January 31, 1936.

15 “Bees Win Last Game; They’re Braves Again,” Boston Herald, April 30, 1941.

16 Newspapers used in this analysis, Brooklyn Eagle (1884-1932), Brooklyn Union (1884), Brooklyn Standard Union (1887-1931), Brooklyn Citizen (1888-1932), Brooklyn Daily Times (1886-1932).

17 “Theaters and Music,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 23, 1890.

18 Thomas Holmes, “Brooklyn Baseball Club Will Officially Nickname Them ‘Dodgers’,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 23, 1932.

19 Newspapers used in this analysis: Chicago Tribune (1874-1907), Chicago Times Herald (1898), Chicago Record Herald (1901-1907), Chicago Daily News (1902-1907), Chicago Inter Ocean (1878-1907), Chicago Journal (1893-1905), Chicago Times (1877-1888), Chicago Post (1903-1904), Chicago American (1901-1904), Chicago Chronicle, (1901-1905).

20 Marc Okkonen, Baseball Uniforms of the 20th Century, Page 105. (New York: Sterling Publishing Company. 1991).

21 Newspapers used in this analysis: Cincinnati Commercial (1882), Cincinnati Commercial Gazette (1886-1887), Cincinnati Enquirer (1882-1890), Cincinnati Times Star (1882-1887), Cincinnati Post (1886-1887).

22 “Red Stockings Become Redlegs in Cincinnati,” New York Times, April 10, 1953.

23 “The ‘Reds’ Are Back in Cincinnati,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, February 12, 1959.

24 Newspapers used in this analysis: New York Times (1883-1912), New York Herald (1884-1907), New York Post (1909-1911), New York World (1884-1885), New York Tribune (1885).

25 “The New-Yorks lose a game to the Champions,” New-York Times, August 16, 1884.

26 Newspapers used in this analysis: Philadelphia Press (1883-1886), Philadelphia Record (1886), Philadelphia Inquirer (1884-1886, 1944).

27 “Phils, not Phillies,” York (PA) Gazette and Daily, February 9, 1942.

28 “Phillies Again,” Greenville, (PA) Record-Argus, March 9, 1943

29 “Phillies Accept Blue Jays as Team Emblem,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 5, 1944.

30 Newspapers used in this analysis: Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette (1882-1899), Pittsburgh Daily Post (1882-1899), Pittsburg Dispatch (1889-1890), Pittsburg Penny Press (1884-1886), Pittsburg Press (1888-1898), Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph (1885-1898).

31 ”Now it is ‘Pittsburgh,’” The Washington Post, August 9, 1911.

32 Newspapers used in this analysis: St. Louis Globe Democrat (1882-1905), St. Louis Post-Dispatch (1882-1900), Missouri Republican (1882-1884), St. Louis Star (1899).

33 “The Brooklyns Here,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 25, 1899.

34 Newspapers used in this analysis: Boston Herald (1901-1907), Boston Globe (1901-1907), Boston Post (1907), Boston Journal (1904-1907), Boston Record (1907).

35 “To Be Known as Red Sox,” The Boston Globe, December 19, 1907.

36 Newspapers used in this analysis: Chicago Tribune (1901-1907), Chicago Record Herald (1901-1903), Chicago Daily News (1902), Chicago Inter Ocean (1902), Chicago Journal (1903), Chicago Post (1903), Chicago American (1901-1903), Chicago Chronicle, (1901-1903).

37 Newspapers used in this analysis: Cleveland Plain Dealer (1901-1915), Cleveland Leader (1901-1906), Cleveland News (1906), Cleveland Press (1901-1906), Cleveland World (1902-1904).

38 “Baseball Writers Select “Indians” as the Best Name to Apply to the Former Naps,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 17, 1915.

39 “Announcement,” Detroit Free Press, July 23, 1922.

40 Newspapers used in this analysis: New York Times (1903-1912), New York Herald (1906-1909), New York Post (1909-1912).

41 Baltimore Sun, 1901-1902.

42 Jim Nasium, “Three Lone Singles Best Macks Made,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1915.

43 Newspaper used in this analysis: St. Louis Globe Democrat (1905).

44 Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel, 1901.

45 Newspaper used in this analysis: The Washington Times (1901-1904), Evening Star (1901-1904).

45 “Senators New Name,” The Washington Post, March 16, 1905.

46 Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Column . . .” The Washington Post, October 31, 1956.

47 Addie column.