Settling the Score: The Story of the First Congressional Baseball Game in 1909

This article was written by J.B. Manheim

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

This article was published in the SABR Deadball Era Committee’s February 2025 newsletter.

The date was July 16, 1909, and there was baseball in the air.1 The catcher showed up in a Panama hat. The left fielder was clad in white flannel trousers with a black silk watch fob dangling from his belt. The third baseman arrived in a suit described by one newspaper as having been stolen from a circus clown. The opposing center fielder—a future Speaker of the House of Representatives— wore a pair of checkered golf trousers tucked into long brown stockings and a silk shirt described in one news account as a “negligee.” The venue for this fashion festival? American League Park in the nation’s capital. The occasion for all of this sartorial sporting splendor? The very first Congressional Baseball Game.

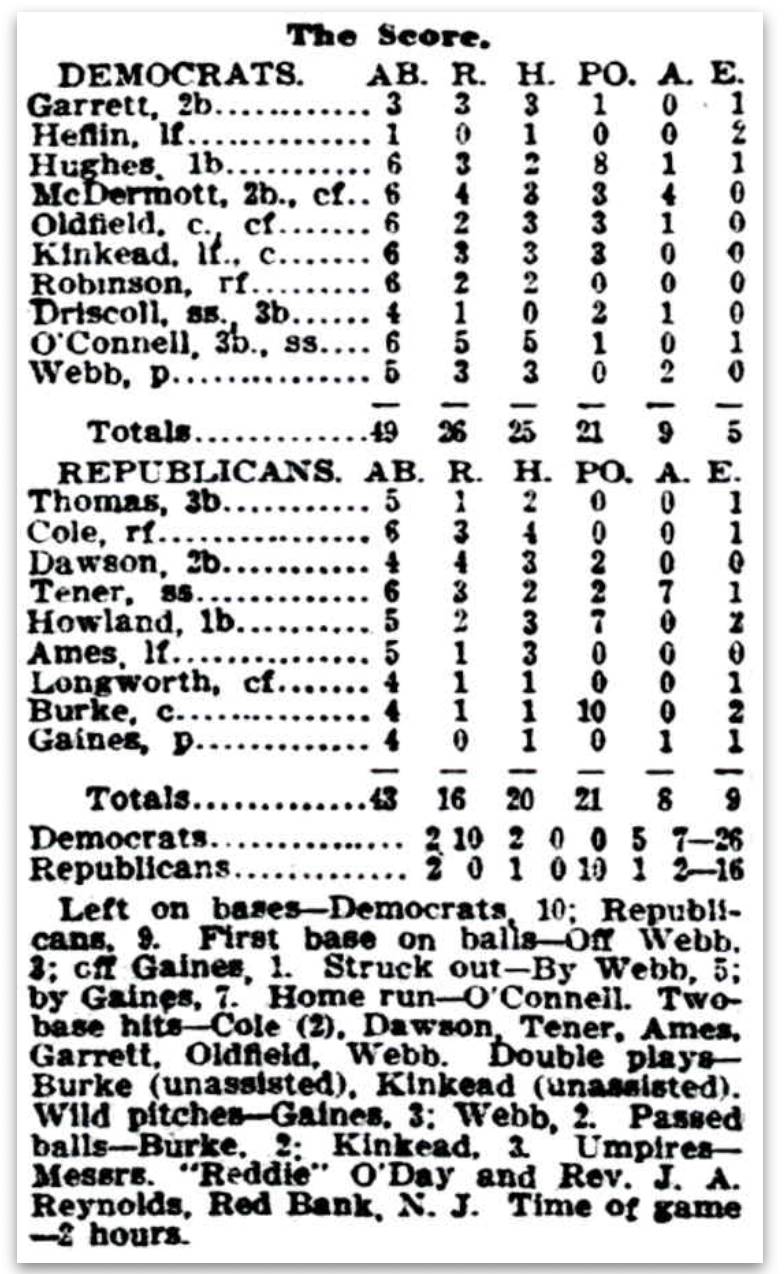

The crowd of spectators was variously estimated to number between four hundred and one thousand, the difference likely being explained by the inclusion of the multitude who entered using free passes. Remember, this is the U.S. Congress about which we are talking. For those in attendance who were focused on the quality of play, the contest was destined to disappoint. The pitching was less than mediocre, but even that out-classed the fielding. Generous scorekeepers among the press on hand tallied only fourteen official errors; it was a charitable estimate. The batting star of the game was obvious—Representative Joseph Francis O’Connell of Massachusetts managed five hits in six trips to the plate, among them the first home run in congressional baseball history. Sort of. The home run ball did not come close to clearing a wall; it simply rolled around in the outfield and by the time it was retrieved and thrown in O’Connell was huffing and puffing toward the plate. He scored only because the catcher, James Francis Burke of Pennsylvania, muffed the throw.

For a time, the contest was nip and tuck. After two innings and a ten-run frame, the Democrats led 12-2. After five innings and a ten-run frame, the score stood at Democrats 14, Republicans 13. But by the end of the seventh, when the game was called because of fatigue and aching muscles, the final tally was 26-16 in favor of the Democrats. According to the box score,2 there were forty-five hits in all, four walks (Vice President Sherman, who did not attend, had decreed that a base on balls would require five balls rather than the customary four, though it is not clear whether this rule was implemented), and twelve strikeouts. The flavor of the game was perhaps best reflected in two particular plays. In one thrilling sequence captured by a newspaper photographer,3 Mr. Burke of the GOP is seen attempting to steal home while his counterpart, William Oldfield of Arkansas, awaits him at home plate, holding up the ball and yelling, “Come to my arms, Jimmy darling.” Unfortunately for Mr. Oldfield, he then simply dropped the ball, and the run scored. In the other play, during the Republicans’ mid-game rally, the watch-fobbed Democratic left fielder, the Honorable J. Thomas Heflin of Alabama, who by then had positioned himself beneath a large tree along the foul line where he was aided by a large dog that he dispatched to retrieve any balls hit in his direction, was presented with a line drive off the bat of Leonard Paul Howland of Ohio, the GOP first baseman, that was headed straight for him. Heflin ducked as the ball sailed by, and Howland should have had a home run. Alas, when he made it to second base he collapsed of exhaustion and called for someone else to come out and finish running for him.

Seated in the front row of the grandstand, with his feet for a time propped up on the railing and his purple stockings in full view, was Joseph “Uncle Joe” Cannon, the Speaker of the House and arguably the most powerful man ever to occupy that position. When it became clear that his Republican charges would fall to ignominious defeat, Cannon, by one account, threw down the large cigar he had been smoking and stomped out of the ballpark to a chorus of derisive catcalls from the Democrats.

But even as the GOP lost the baseball game, Cannon himself was the winner in a much larger contest. For this was a story less about a baseball game than about political gamesmanship. The “game” was played to serve the purposes of the chief gamesman. And at least in the short run, it performed that task quite well.

Congressman Edward Vreeland.

PLAYING BALL ON THE HILL

Joe Cannon had a problem, albeit one of his own makings, and a little inside baseball between the two parties— both on and off the field—would buy him the time to solve it. To understand why the game on the field was played, we first need to understand the game that was being played in the House. As in all things “Washington,” that means we need to follow the money.

Until 1909 the government had remained small. It was funded primarily by a highly protectionist tariff system. But an emerging movement, the progressives, saw the high tariffs mainly as protecting the trusts, fast growing and powerful industrial corporations which they were intent on reining in, and they demanded reform. To replace the revenue that they knew would be lost in the process, and to fund the growth in more aggressive government regulatory initiatives—a.k.a. trustbusting—that they craved, the progressives also backed new alternative forms of taxation, including the imposition of a personal income tax. A recent court decision had made clear that the latter could not be enacted without amending the Constitution.4

Standing against this was a conservative majority of Republicans in the House of Representatives led by Speaker Cannon, along with a similarly protectionist-minded majority in the Senate.

Cannon, who was a sharp operator—savvy, cagey, determined, and often vindictive—had seen the legislative battle over tariffs coming, and in the prior Congress he had pressed his colleague, Sereno Payne, who was both majority leader and Chair of the Ways and Means Committee, to take a deep dive into the tariff structure and prepare a bill that would not be introduced until 1909—after the 1908 election. In March 1909, a newly elected President Taft called for a special session of Congress to deal with tariffs. Cannon then promptly had Payne bring forward his legislation, which gave every appearance of responding to the progressives’ demands for tariff reform. But appearances were the point; Cannon and Payne had no intention of allowing for the passage of true reform. To the contrary, they adopted a highly cynical strategy of encouraging the reformers in public while assuring that in the end they would fail.

Payne’s bill was introduced in March, debated briefly, then passed in April and sent to the Senate, where it came under the control of fellow protectionist Nelson Aldrich, Chair of the Finance Committee. Aldrich stewarded the bill through nearly three months of open debate, in the course of which it was amended 847 times—always in the direction of greater protectionism. While this was happening, all the Democrats and Progressive Republicans in the House could do was to watch. That was because Speaker Cannon, who had wide-ranging powers, refused to name any legislative committees in the House until the tariff bill was passed in final form and signed by the president. Since the committee process was then as now the lifeblood of Congress, this meant that literally nothing substantive could happen in their absence.

The only exception to this came in June, when the proposed Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution, authorizing the personal income tax, was rushed through the House with the complete support of the Speaker and his allies, who opposed the tax itself but backed the amendment for two reasons: they knew it would assuage the progressives, who were becoming increasingly restless, by continuing the fiction that the House would pursue a reformist agenda, and they were confident that the requisite number of states would never vote for ratification.

In the meantime, Washington’s typical summer weather— intense heat and humidity—began to build in earnest. And though mechanical air conditioning had been invented by Willis Carrier a few years earlier, the Capitol Building was three decades away from installing it. The weather, then, combined with the enforced inactivity of the body and the Speaker’s increasingly obvious circumvention of efforts at tariff reform, was generating another kind of heat in the halls of Congress. The mixture of frustration, anger, boredom, and impatience was boiling over. Something had to be done.

On Day 100 of the confrontation, the House leadership moved toward cooling off the situation, at least long enough to complete passage of the bill.

TAKE IT OUTSIDE! THE GENESIS OF THE CONGRESSIONAL BASEBALL GAME

On that day, June 23, three weeks before the competing nines would square off at American League Park, a caravan of sorts—a pair of touring cars—set out from the Willard Hotel in Washington for Oriole Park in Baltimore, some forty miles away.5 Members of the party could have taken the electric rail service that ran every half hour between downtown Washington and central Baltimore, a one-hour trip. But they opted instead to make the drive, a two-hour journey at best over a poorly delineated and at points lightly maintained network of county and state roads marked by multiple rough railroad grade crossings. Car trouble along the way delayed the group even further, but that was acceptable because most likely the real purpose of the drive was to provide an opportunity for some private, uninterrupted strategizing, and the longer trip allowed for more conversation.

In one auto rode Sereno Payne, two fellow Republican congressmen, one a member of Payne’s Ways and Means Committee, and a tariff lobbyist. In the other were newly elected congressman John Tener, two other Republicans, and a lone Democrat who had already cut a deal on a product-specific tariff. A ninth participant, the recently retired Republican House whip, met the group once they eventually reached their destination. While we cannot know what was said during the drive, it is amply clear that, once at the ballpark, all of the discussion within the group and with reporters at the game focused on the dominant issue of the day, the tariff bill.

John Tener was the first former major leaguer to be elected to Congress. Tener pitched two seasons for the Chicago White Stockings in the late 1880s, participated in the Spalding World Tour of 1888-89 (where he did double duty as treasurer of the venture and Spalding’s personal secretary and was the participant selected to explain the game of baseball to the future King Edward VII when the tour reached England), and many years later would serve as president of the National League. In the course of the tour, Tener became fast friends with Ned Hanlon, who recruited him to the Pittsburgh entry in the short-lived Players League in 1890. When the league folded, Hanlon returned to the baseball career that would lead him to the Hall of Fame, while Tener, who was from the Pittsburgh area, began a career in banking and other businesses. By 1909, Hanlon was owner of the Baltimore Eastern League team. We know that the congressional junket to Baltimore was arranged in the course of a telephone call between Tener and Hanlon on June 22. This fact has led historians to conclude that it was Tener who originated the idea for the initial congressional matchup. But that overlooks evidence to the contrary. There were other claimants to this title, perhaps most credibly Congressman Edward Vreeland of New York. Vreeland was a Republican insider and would be named to chair the Banking Committee once Cannon resumed the normal conduct of business in the House.6 Vreeland and Tener were both bankers from the western parts of their neighboring states and may have known each other professionally. But regardless, chances are that upon arriving in Congress banker Tener, who continued in the business during his term, would have sought out Vreeland in any event and Vreeland, a baseball fan, would have been open to such a gesture.

Vreeland was originally scheduled to make the trip to Baltimore but begged off at the last minute. However, it is quite possible that he had a conversation beforehand with Payne, another close follower of baseball, or even Cannon, where he shared the idea for the game. Whatever the case, it was immediately after the Baltimore visit that planning began for the congressional contest.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Tener was the face of organizing the GOP roster, while Champ Clark, the minority leader, organized the Democrats. But there are reasons to believe that Tener’s role was limited. For one thing, almost none of the players he named in his first lineup actually played in the game. The entire group, save one, was changed at the last minute. In contrast, the initial Democratic lineup changed very little by game day. But more fundamentally, there was a great deal more involved in organizing the game than simply naming the players. A field had to be located and reserved, tickets and passes needed to be printed and distributed, vendors and stadium staff needed to be recruited, the charity that would benefit from the gate had to be selected, funds needed to be collected and, following the game, distributed to the chosen charity, and more. John Tener was, in reality, a one-term congressman with an abysmal voting record,7 limited staff support, and no particular institutional interest. He was useful to the leadership mainly as a minor celebrity who could serve as the face of the game and attract participants and spectators from the political class and the media. And that was precisely what the leadership needed if the baseball game were to serve its primary purpose—as a pleasant distraction that could buy a little time.

Another indicator of the probable limits of John Tener’s role is the makeup of the Baltimore travel party. If he had been the moving force behind that trip, one thing he almost surely would have done would have been to assure that he rode in the same auto as his most powerful companion, Mr. Payne. But Payne and Tener rode in separate vehicles. Moreover, given that Tener, during his congressional tenure, displayed no strong policy interests whatsoever, it would seem more likely that he would have selected friends and acquaintances to accompany him to Baltimore rather than a bunch of tariff experts. He almost surely knew one member of the party, lobbyist J.B. Fischer, because Fischer had served on the national board of the Elks organization around the time when Tener had been that group’s Grand Exalted Ruler, its top national leader. But as to the others there is no obvious personal link.

One final point in this regard. Given that the 1909 congressional game was, on its own merits, a political success that achieved media attention and public approbation, if Tener had been truly motivated by the idea he would most likely have organized a second contest the following year, 1910. He did not. The second game in the series was not played until 1911, when Tener was back in Pennsylvania serving as the state’s governor.

Whatever the details of the planning, the “athletes” representing their respective parties took the field at American League Park on July 16, just three weeks after that trip to Baltimore. Comments by the players themselves during the course of the afternoon were replete with references to the tariff bill, and news accounts both before and after commonly used the legislation and the state of the House as a frame for their game coverage. As the Boston Globe put it on the day of the game in an article headlined, “Greater Issue Than the Tariff: All Washington Excited Over the Congressional Ball Game.”

The conference on the tariff, the urgent deficiency bill [today we would call this a supplemental appropriation], and in fact all other legislation has been forgotten. Plastered all over the lobby, back of the speaker’s desk and in the cloak, rooms are big notices that the game will be pulled off today. It is a rare event indeed, when the sacred precincts of the house [sic] contain a notice of anything except to keep off the grass or to stay out of the private elevators, but in this case all rules have been swept to the winds.8

The Cincinnati Enquirer echoed the theme in its next-day recap:

The Democrats pounded the ball in much the same spirit they would hammer away at the tariff bill if “Uncle Joe” Cannon gave them half a chance, while the teamwork of the Republicans was as disjointed as their views are on the subject of raw materials and downward revision. There is only one way for the Republicans to get even, and that is through a series of special rules, which Speaker Cannon devises, containing every ingeniously cruel limitation upon the already curtailed privileges of the minority in the House….9

Or, as one unnamed Democratic participant put it: We had scores to settle, and this sort of partly evens things up, though I’m rather afraid that “Uncle Joe” will plant his foot more firmly on some of our necks to get back at us.10

1909 Congressional Game Box Score

HARDBALL ON THE HOUSE FLOOR

At the end of July, just a few days after the game, the Senate passed and returned to the House its amended, and far more protectionist, version of the tariff bill, now referenced jointly as the Payne-Aldrich Bill. The House promptly rejected the Senate version and sent it to conference for reconciliation. This was the critical point in the Speaker’s strategy, for Cannon, in concert with Senator Aldrich, controlled the conference committee, which promptly reported out a “final” version of the bill —one that incorporated all 847 Senate amendments. Through his control of the Rules Committee, which set the terms for floor consideration of all legislation, the bill was presented with virtually no opportunity for debate, and none at all for other than technical (proof-reading) amendments. It passed the House on August 5, 1909. President Taft, who had been waiting in a room just off the House chamber, signed Payne-Aldrich into law just minutes later.

Literally five minutes after the bill became law, recorded beginning on the very same page of the Congressional Record,11 Speaker Cannon proceeded to name members to all of the House committees of the 61st Congress, taking care to reward those who had helped him on the tariff, after which the House immediately adjourned the special session. Members would not return until December.

Uncle Joe had won the battle, but the victory was pyrrhic. In the next (1910) session of the House, in a clear repudiation, the Speaker’s powers were sharply reduced. No Speaker since Cannon has wielded such control of the body. In the 1910 election, Democrats reclaimed the House itself, making Champ Clark the Speaker. In the next Congress, the Payne-Aldrich tariffs were replaced by a much less protectionist regime. And not long afterward, the Sixteenth Amendment was ratified by the states and incorporated into the Constitution. Not surprisingly, it did not take Congress long to begin taking advantage of this new power.

All of Cannon’s political machinations, then, in the long term were for naught. But in the moment—at a critical time in the political game—the very first congressional baseball game had played its part. It is perhaps worth noting that the 2025 Congressional Baseball Game, the ninetieth to be contested between the two parties, comes at a time when tariffs, progressivism, and internal factional disputes are once again at play in Congress.

J.B. MANHEIM was founding director of the School of Media & Public Affairs at The George Washington University and is a past chair of the Political Communication Section of the American Political Science Association. He is author of The Deadball Files, an award-winning series of present-day mysteries and legal thrillers grounded in events of the Deadball Era and, with Lawrence Knorr, co-author of What’s in Ted’s Wallet? The Newly Revealed T206 Baseball Card Collection of Thomas Edison’s Youngest Son. This article is based on his latest book, The House Divided: The Story of the First Congressional Baseball Game, which will be published in spring 2025 by Sunbury Press.

NOTES

1. The much abbreviated account that follows is based on an amalgam of the information, often overlapping, provided in the following sources: “Democrats Win Real Ball Game,” Washington Herald, July 17, 1909, 1, 9; “Carnage Is Something Awful When Those Big Swatting Democrats Cut Loose: Republican Ball Team Ground into Dust,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 17, 1909, 1, 2; “De-mocrats Win Baseball Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 17, 1909, 4; “Arkansas, Alabama and Tennessee Stars, Who Figured in the Recent Congressional Baseball Game,” Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), July 23, 1909, 8; “Democrats Score Their Only Victory of the Extra Session,” Nashville Banner, July 17, 1909, 3; “Solons Play Ball,” Washington Post, July 17, 1909, 1, 4; “List of Cripples Numbers Twenty,” Washington Times, July 17, 1909, 4; Mary Craig, “A Comedy of Errors: The First Congressional Baseball Game,” The Hardball Times, April 10, 2017, accessed July 9, 2024, at tht.fangraphs.- com/a-comedy-of-errors-the-first-congressional-baseball-game; and Robert Pohl, “Lost Capitol Hill: The First Congressional Baseball Game,” February 27, 2012, accessed July 11, 2024, at thehillishome.com/2012/02/lost-capitolhill-the-first-congressional-baseball-game.

2. See, for example, “Democrats Win Real Ballgame,” op. cit., 9.

3. See “Arkansas, Alabama, and Tennessee Stars…,” op. cit.

4. The 1895 case, in which the Supreme Court reversed a previous decision, was Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Company. See Cynthia G. Fox, “Income Tax Records of the Civil War Years,” Prologue Magazine, Winter 1986, 18:4, passim.

5. See, for example, “Ned Hanlon As Host: He Will Enter-tain a Congressional Party at Oriole Park,” Baltimore Sun, June 23, 1909, 10; “Noted Men to See Game: Represen-tatives From Several States to Be Guests of President Hanlon,” Washington Evening Star, June 23, 1909, 14; and “Congressmen on Tariff: Visitors to Baseball Game Talk Of ‘Revision Downward,’” Baltimore Sun, June 24, 1909, 12.

6. “Rep. Vreeland Is Doing Well,” Buffalo Evening News, July 16, 1909, 1.

7. Voting data are drawn from “Rep. John Tener,” accessed July 2, 2024, at www.govtrack.us/congress/members/ john_tener/410707.

8. “Greater Issue Than the Tariff,” Boston Globe, July 16, 1909, 8.

9. “Carnage Is Something Awful…,” op. cit.

10. “Solons Play Ball,” op. cit., 1.

11. Congressional Record–House, Vol. 44, Part 5 (Washington: United States Congress), August 5, 1909, 5088.