Shifting Expectations: An In-Depth Overview Of Players’ Approaches To The Shift Based On Batted-Ball Events

This article was written by Connelly Doan

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

One of the hottest and most polarizing topics in baseball today is the increasing implementation of the defensive shift. The idea of the shift itself is not new; teams started using the “Ted Williams Shift” — moving four infielders and two outfielders to the right side of the field — in 1946 to increase their chances of getting the great hitter out, while less dramatic shifts existed before that.1 The strategy was used sparingly until the revolution in statistical analysis spurred a strong revival of the tactic. A glut of stats on batted-ball outcomes and defensive metrics has been coupled with data-driven processes to find efficient solutions to improving the outcomes of the game. The use of the shift has grown significantly over the past decade.2

One of the hottest and most polarizing topics in baseball today is the increasing implementation of the defensive shift. The idea of the shift itself is not new; teams started using the “Ted Williams Shift” — moving four infielders and two outfielders to the right side of the field — in 1946 to increase their chances of getting the great hitter out, while less dramatic shifts existed before that.1 The strategy was used sparingly until the revolution in statistical analysis spurred a strong revival of the tactic. A glut of stats on batted-ball outcomes and defensive metrics has been coupled with data-driven processes to find efficient solutions to improving the outcomes of the game. The use of the shift has grown significantly over the past decade.2

Much of the focus given to the shift falls into two categories. The first is a debate between whether the shift is good or bad for baseball. Sportswriters, players, and broadcasters have voiced their displeasure over how the shift has taken away from “the way the game should be played.”3, 4, 5 Commissioner Rob Manfred even considered banning the shift in 2015.6 The second category consists of various analyses, both defensively and offensively, attempting to pinpoint the effectiveness of the shift, to assess whether or not it “works” based on various statistics and metrics.7, 8

This paper falls into the second category but will focus more on hitters’ and pitchers’ approaches to dealing with the shift, rather than merely the outcomes of the shift. It is easy to say that hitters could just bunt or hit to the opposite field when shifted on, but an in-depth overview of shift outcomes based on hard data would be a welcome addition to the discussion. To help fill this void, this paper will present an overview of shift batted-ball events from the beginning of the 2017 season through the first half of the 2018 season. Further, it will identify patterns in the data regarding both hitters’ and pitchers’ approaches to the shift. Finally, conclusions will be drawn in an attempt to explain why shift outcomes occurred as they did and to identify further topics of analysis. Understanding how players approach the shift in addition to understanding the tactic itself will offer insight into its effectiveness.

Data Overview/Methods

The data for this article were scraped from MLB’s BaseballSavant.com using RStudio codes and packages based on Bill Petti’s BaseballR.9

Specifically, the raw data comprised complete game events from every game of the 2017 season through the first half of the 2018 season where an infield shift was on. Events are play outcomes, either batted balls, strikeouts, walks, or baserunning plays such as steals.

The raw data were then loaded into Microsoft Power BI to filter the data and create interactive charts and graphs for further analysis. The data were first filtered on Baseball Savant’s IF Alignment measure. This measure is broken down into three options:10

- standard — no shift

- shift — three infielders on one side of the infield (“traditional shift”)

- strategic — a catch-all for plays in which the infield was neither standard nor traditionally shifted

This article uses only events featuring the traditional shift. The filtered dataset contained approximately 37,000 batted-ball events.

The data were then broken down by batter handedness as well as pitch locations of left-hand side of the plate, middle of the plate, and right-hand side of the plate. Pitch locations were labeled by aggregating Baseball Savant’s Gameday zones. Various tables and graphs were then created for left-handed and right-handed batters to compare how shift performance differed in batter handedness and to compare if pitchers approached hitter handedness differently in shift situations.

Results

General

Of the approximately 37,000 events in the data, 27,117 occurred against left-handed batters (referred to as lefties from here on) and 9,928 occurred against right-handed batters (referred to as righties from here on). Teams shifted about three times as often against lefties than righties. Righties hit significantly better than lefties against the shift, both in terms of batting average (.259 vs .232) and slugging average (.477 vs .429).

The differences in shift events and righties’ relative success hitting against the shift compared to lefties could be explained a few ways. First, righties may just be better hitters than lefties. Second and seemingly more likely is that the physical differences in the shift benefit righties over lefties. A shift against lefties brings the shortstop closer to first base and doesn’t significantly alter the second baseman’s distance. A shift against righties draws both the second baseman and shortstop further away from first base, so even if a righty does put the ball in play into the shift, they have a better chance of getting a hit due to the increased difficulty of the throw to get an out.

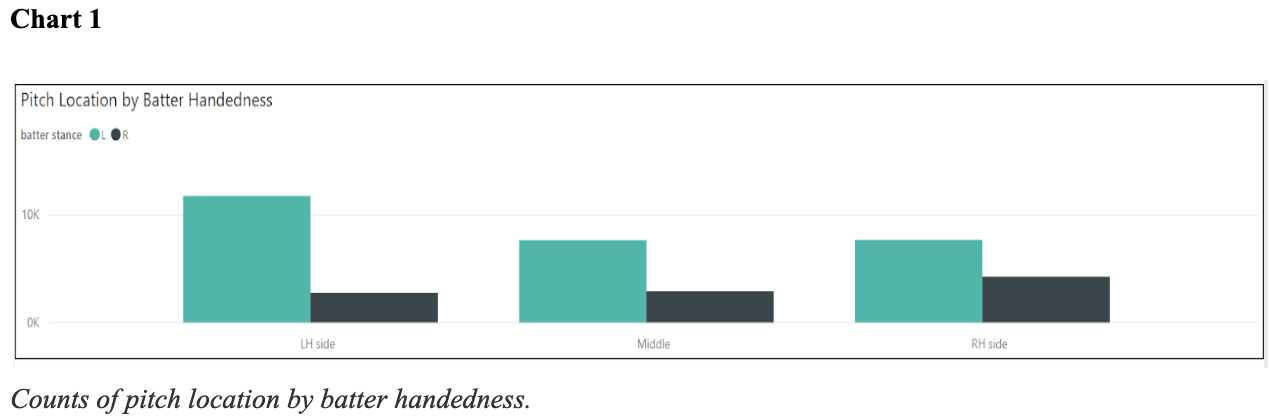

In terms of pitch location, both lefties (.246 vs .197) and righties (.264 vs .242) had higher batting averages on pitches thrown down the middle or on the inside part of the plate compared to pitches thrown to the outside of the plate. However, pitchers pitched into the shift more often than not, regardless of batter stance (see Chart 1).

(Click image to enlarge)

Given that most of the opposite side of the infield is open when the shift is on, it may make sense intuitively for pitchers to pitch into the shift, but these data show that hitters were more successful on balls in play on middle/in pitch locations.

Approach to Hitting Against the Shift

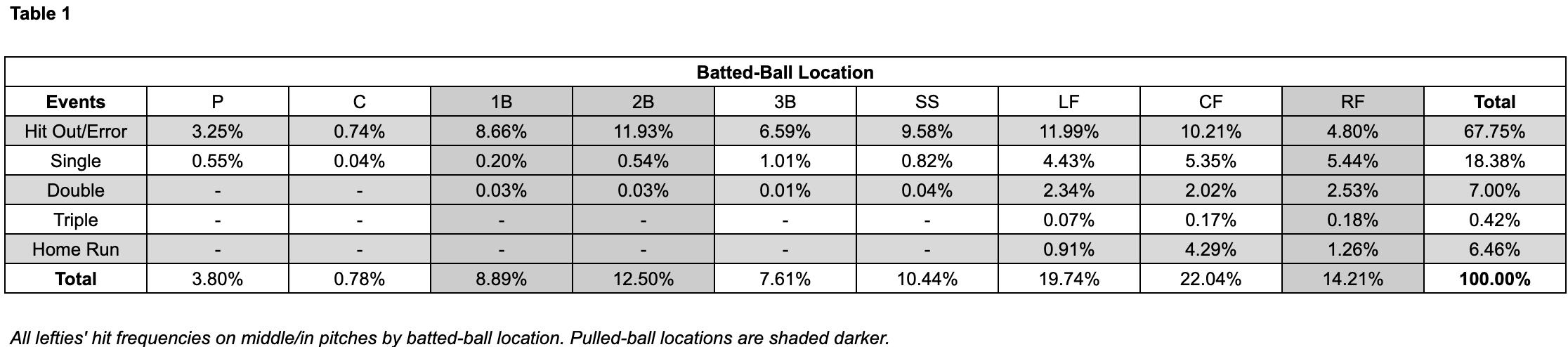

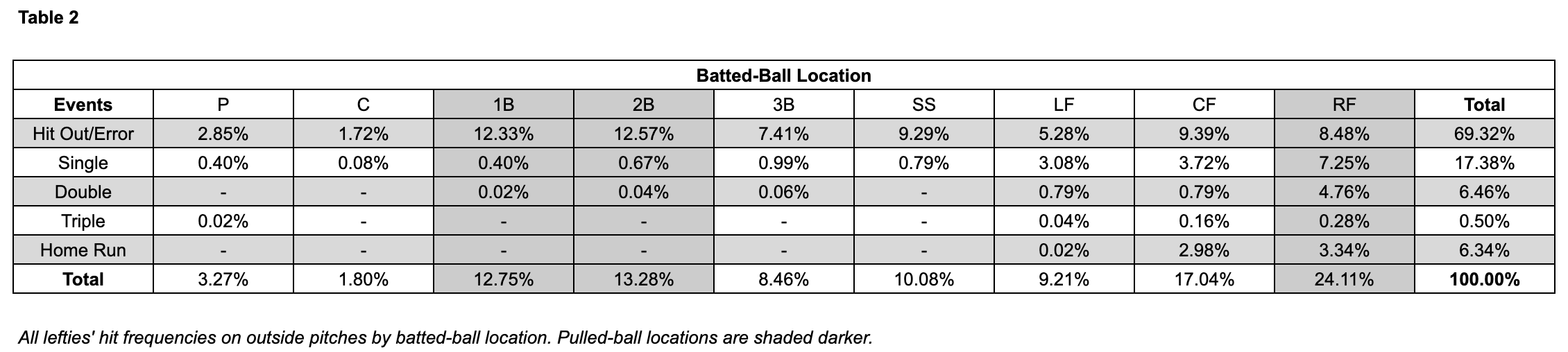

Tables 1 and 2 show the outcomes of batted-ball events for lefties on middle/in and outside pitches, respectively.

(Click images to enlarge)

Given the imprecise reporting of batted-ball location in shifted infield positions (it is unclear where exactly the shortstop was positioned in the shift for a lefty or where the second baseman was positioned for a righty), I will only consider batted-balls to positions where the fielder’s location is more clearly known. An important caveat to this is that third basemen will sometimes move into shallow right field when shifting against lefties, while the shortstop will move to the left side of the infield.11

As noted above, a limitation of this article is the imprecise reporting of infielder positioning on batted-balls. As such, I will treat the third baseman’s position as “known” (where the shortstop would typically play in a non-shift situation) for lefty batted-balls. Of 19,434 batted balls on middle/in pitches, lefties hit to both sides of the field fairly evenly (35.60% of balls hit to first base, second base, right field; 27.35% hit to third base, left field). On the other hand, of 7,682 batted balls on outside pitches, lefties pulled the ball much more frequently than hitting to the opposite field (50.14% of balls hit to first base, second base, right field; 17.67% hit to third base, left field). Lefties’ batted-balls resulted in outs or errors 67.75% of the time on middle/in pitches and 69.32% of the time on outside pitches.

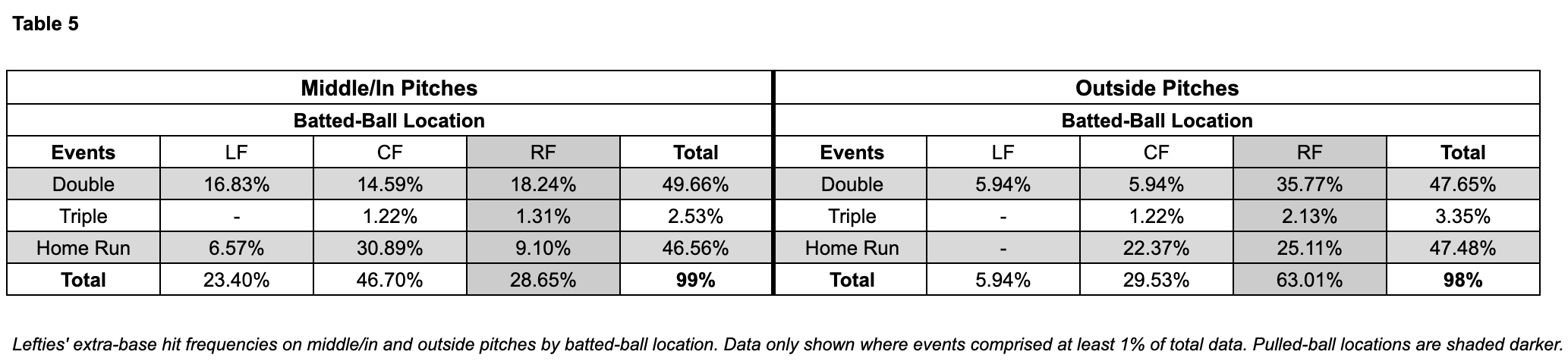

Breaking down lefties’ batted balls further, Table 5 shows the batted-ball locations of extra-base hits on middle/in and outside pitches.

(Click image to enlarge)

Of the 2,713 extra-base hits that occurred with the shift on for lefties, 2,056 came on middle/in pitches and 657 came on outside pitches. Of the extra-base hits on middle/in pitches, 28.65% of them were hit to right field and 23.88% to left field. Of the extra-base hits on outside pitches, 63.01% of them were hit to right field while only 6.39% were hit to left field. In sum, lefties pulled the ball significantly more often than hitting to the opposite field on outside pitches and hit to both fields on middle/in pitches. Lefties hit for power by pulling the ball on outside pitches and were able to go to both fields for power on middle/in pitches.

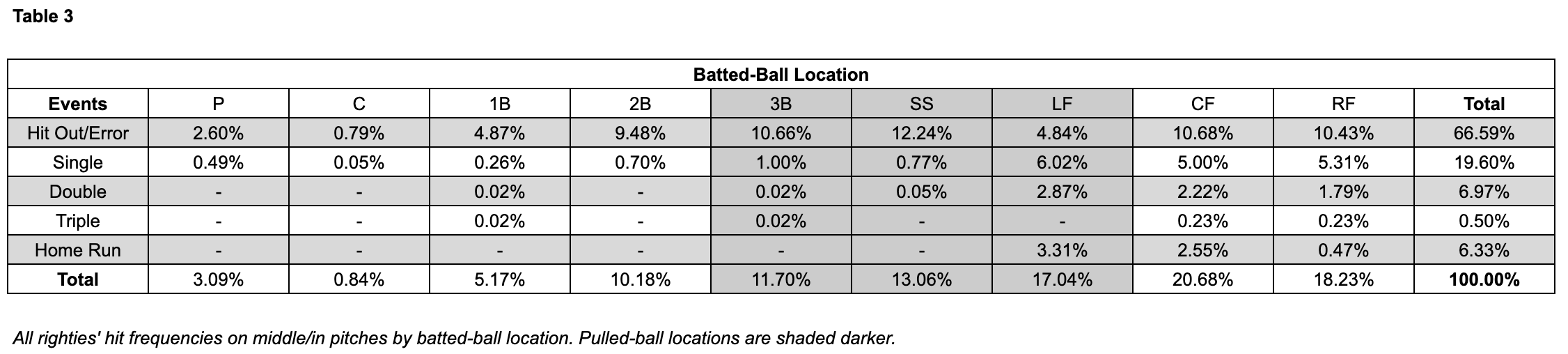

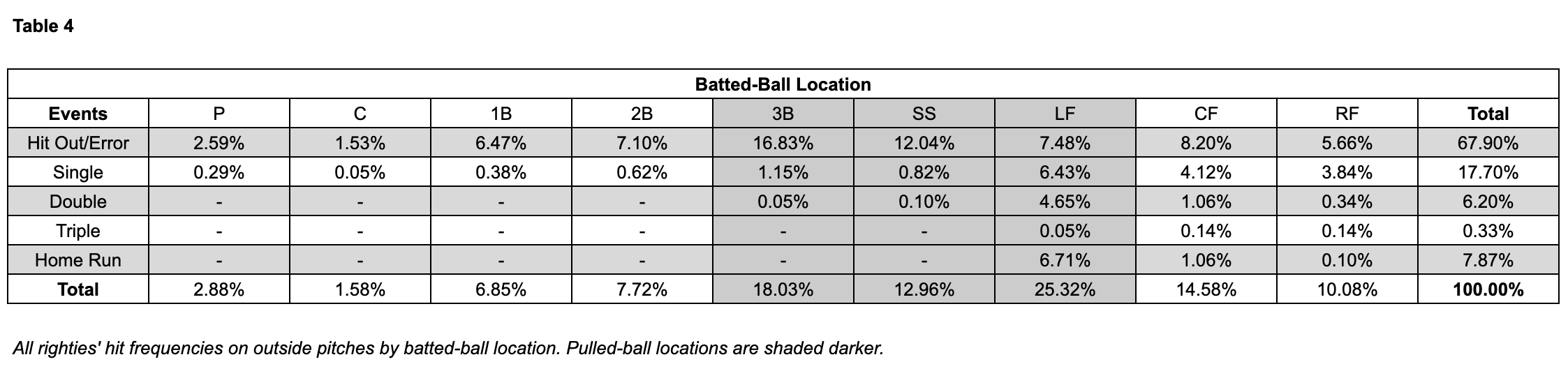

Righties’ batted-ball tendencies mirrored lefties’ in many ways. Tables 3 and 4 show the outcomes of batted-ball events for righties on middle/in and outside pitches, respectively.

(Click images to enlarge)

Of 7,174 batted balls on middle/in pitches, righties pulled the ball about twice as often as going to the opposite field (41.80% of balls hit to third base, shortstop, left field; 23.40%% hit to first base, right field). Of 2,754 batted balls on outside pitches, righties pulled the ball much more frequently than hitting to the opposite field (56.31% of balls hit to third base, shortstop, left field; 16.93% hit to first base, right field). Righties’ batted-balls resulted in outs or errors 66.59% of the time on middle/in pitches and 67.90% of the time on outside pitches.

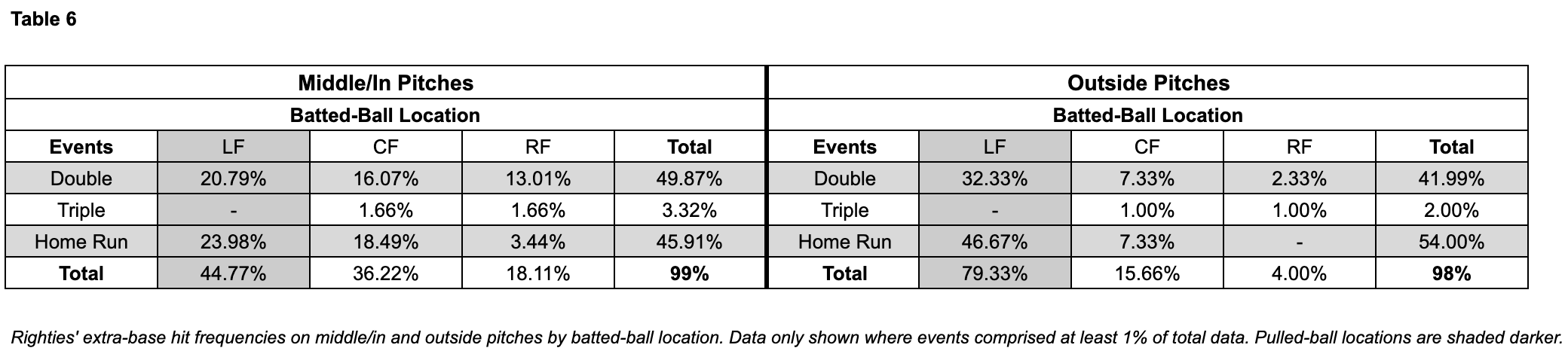

Table 6 shows the batted-ball locations of extra-base hits on middle/in and outside pitches.

(Click image to enlarge)

Of the 1,084 extra-base hits that occurred with the shift on for righties, 784 came on middle/in pitches and 300 came on outside pitches. Of the extra-base hits on middle/in pitches, 44.77% of them were hit to left field while just 18.11% were hit to left field. Even more lopsided, of the extra-base hits on outside pitches, 79.33% of them were hit to left field while a mere 4% were hit to right field. Like lefties, righties hit to both fields on middle/in pitches and pulled the ball significantly more than hitting to the opposite field on outside pitches. Unlike lefties, righties hit for power mostly by pulling the ball, regardless of pitch location.

Takeaways and Explanations

After reviewing a season-and-a-half’s worth of batted-ball shift events at a deep descriptive level, several patterns emerged. First, all hitters performed better on middle/in pitches with the shift on in terms of batting average, slugging average, and avoiding getting out. More often than not, however, pitchers threw to that side of the plate. Further, hitters pulled the ball significantly more than hitting to the opposite field on outside pitches and hit to both fields somewhat evenly on middle/in pitches. Finally, lefties found success in hitting for power on outside pitches by pulling the ball and generated power to both fields on middle/in pitches. Righties, conversely, mostly generated power in the shift by pulling the ball, regardless of pitch location.

These tendencies present evidence that is counterintuitive to how one would think to approach the shift, but there may be some explanation behind how hitters and pitchers have approached it. There are several plausible explanations regarding hit location versus pitch location. First, hitters may be taking middle/in pitches to the opposite field because they are getting jammed or are slightly late on those pitches. Pitchers’ average velocity has increased over the years.12

Consequently, hitters have less time to react and are more likely to swing late. Another explanation could be that hitters are just more comfortable controlling pitches on the inner half of the plate off of their bats. The data from this project indicate that all hitters had higher batting averages, greater number of extra-base hits, and a relatively equal amount of hits to both fields on middle/in pitches. Perhaps hitters can handle middle/in pitches better, and can therefore actually better-strategically execute hitting the ball away from the shift on those pitches.

Two explanations arise to address batted-ball outcomes of outside pitches. First, hitters may have more trouble handling outside pitches compared to middle/in pitches; perhaps hitters are just not as successful at executing on outside pitches, especially in situations in which they are attempting to bunt for a hit.13

What seems more likely, however, is that hitters are set on hitting over the shift to beat it. Hitters have become increasingly more strategic and calculated in terms of valuing how and where they hit the ball. The mass quantities of data that are now available have enabled coaching staffs and players to better analyze game outcomes based on attributes of their swings. A clear example of this is the prevalence of players who have increased their launch angles to hit over the shift, a phenomenon known as the Flyball Revolution.14 A cost-benefit analysis occurs for the hitter: what is more valuable to the team, a “free” single to the opposite field or a double or home run hit into or over the shift?15 The overwhelming number of pulled balls on outside pitches suggest that hitters may be making a conscious effort to not hit with the pitch.

Understanding pitchers’ approaches to the shift is more straightforward than understanding hitters’ approaches. Pitchers were pitching into the shift because it logically makes sense; if three of your infielders are gathered on one side, why not attempt to get the hitter to hit the ball to that side by pitching the ball to that side of the plate? However, based on the data presented and the above discussions on hitters’ approaches to hitting against the shift, it actually seems detrimental for pitchers to pitch into the shift. Hitters perform better on middle/in pitches overall and are rarely hitting the ball to the open opposite field on outside pitches. Until hitters can make the mental or physical adjustments to make the pitcher pay for pitching to the open side of the field, pitchers should attack the outside part of the plate when the shift is on. While it may be a mental hurdle in itself for pitchers to throw to the exposed side of the field, the data show that they would be more successful doing so.

Next Steps

This article provides an in-depth dive into batted-ball shift outcomes and offers insight into both hitters’ and pitchers’ approaches to handling the shift, but it is just the beginning in terms of understanding the shift and how players perform in it. There are several avenues of study that could follow this article.

The first could be a comparison of how hitters and pitchers perform in non-shift situations versus shift situations. While it is not necessary to identify patterns in shift situations, comparing non-shift outcomes could shed light onto how hitters and pitchers think about the shift and how they may attempt to adjust their approach (or not) to be successful. Such a comparison would also be useful at a single-player level to identify players who are relatively more successful in shift situations. This would allow for a more granular study analyzing the effectiveness of the shift.

The second could be the addition of non-batted-ball outcomes to analysis similar to that in this article. Identifying tendencies in batted-ball outcomes only provides a partial understanding of hitters’ and pitchers’ approach to the shift as a whole. Russell Carleton presented analyses on shift expected outcomes at Baseball Prospectus and found that, while the shift decreased the number of singles pitchers allowed, it increased walks to a greater extent. Pitchers felt uncomfortable pitching with the shift on and, therefore, ended up pitching less effectively.16 Analyses such as these provide key insights into players’ approaches to the shift that batted-ball outcomes alone cannot.

CONNELLY DOAN, MA, is a Data Analyst in the San Francisco Bay Area who has applied his professional skills to the game of baseball, both personally and for RotoBaller.com. He has been a SABR member since 2018. He can be reached on Twitter (@ConnellyDoan) and through email (doanco01@gmail.com).

Notes

1 Neil Paine, “Why Baseball Revived a 60-Year-Old Strategy Designed to Stop Ted Williams,” FiveThirtyEight, October 13, 2016, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/ahead-of-their-time-why-baseball-revived-a-60-year-old-strategy-designed-to-stop-ted-williams/.

2 Travis Sawchik, “We’ve Reached Peak Shift,” FanGraphs, November 9, 2017, https://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/weve-reached-peak-shift/.

3 Matt Snyder, “MLB Shifts Are Starting to Get More and More Excessive, so Are We Headed to a Bad Place Where Positions Don’t Matter?,” CBS Sports, May 17, 2018, https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/mlb-shifts-are-starting-to-get-more-and-more-excessive-so-are-we-headed-to-a-bad-place-where-positions-dont-matter/.

4 Alden Gonzalez, “How the Shift has Ruined Albert Pujols,” ESPN, August 7, 2018, http://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/24270231/mlb-how-shift-ruined-albert-pujols.

5 Tom Hoffarth, “Sports Media: Hall of Famer John Smoltz Not Exactly What the Viewers This Time of Year are Looking for,” Los Angeles Times, October 15, 2018, https://www.latimes.com/sports/la-sp-sports-media-20181015-story.html.

6 Emma Baccellieri, “Proposing a Shift Ban is Easy, but How Would MLB Implement One?,” Sports Illustrated, July 25, 2018, https://www.si.com/mlb/2018/07/25/defensive-shifts-official-baseball-rules.

7 Russell A. Carleton, “Baseball Therapy: Why the Shift Persists,” Baseball Prospectus, January 3, 2018, https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/36897/baseball-therapy-shift-persists/.

8 Russell A. Carleton, “Baseball Therapy: The Pretty Good Case That the Shift Doesn’t Work,” Baseball Prospectus, May 3, 2016, https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/29085/baseball-therapy-the-pretty-good-case-that-the-shift-doesnt-work/.

9 “Baseballr: A Package for the R Programming Language,” baseballr, last modified May 29, 2018, http://billpetti.github.io/baseballr/.

10 “MLB Statcast Shifts,” MLB, accessed March 3, 2019, http://m.mlb.com/glossary/statcast/shifts.

11 Ben Lindbergh, “Overthinking It: Defining Positions in the Age of the Shift,” Baseball Prospectus, May 28, 2014, https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/23705/overthinking-it-defining-positions-in-the-age-of-the-shift/; David Waldstein, “Who’s on Third? In Baseball’s Shifting Defenses, Maybe Nobody,” The New York Times, May 12, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/13/sports/baseball/whos-on-third-in-baseballs-shifting-defenses-maybe-nobody.html.

12 Anthony Castrovince, “Speed Trap: How Velocity has Changed Baseball,” MLB.com, April 2, 2016, https://www.mlb.com/news/increase-in-hard-throwers-is-changing-mlb/c-170046614.

13 Jon Weisman, “Why MLB players Don’t Bunt Against the Shift,” Dodger Thoughts, October 9, 2018. https://www.dodgerthoughts.com/2018/10/09/why-mlb-players-dont-bunt-against-the-shift/.

14 Dave Sheinin, “Why MLB Hitters Are Suddenly Obsessed With Launch Angles,” Washington Post, June 1, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/sports/mlb-launch-angles-story/?utm_term=.79f08e1ac9a0.

15 Jerry Crasnick, “MLB Hitters Explain Why They Can’t Just Beat the Shift,” ESPN, July 10, 2018, http://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/24049347/mlb-hitters-explain-why-just-beat-shift.

16 Russell A. Carleton, “Baseball Therapy: How to Beat the Shift”, Baseball Prospectus, May 22, 2018, https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/40088/baseball-therapy-how-beat-shift/.