George Sisler Confronts the Evil Empire

This article was written by Roger A. Godin

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 25, 2005)

George Sisler returned to action in 1924 after solving the eye problem that had kept him out of the 1923 season. He would not only return to holding down first base in his usual superb manner while resuming his customary .300+ hitting, he would now be the Browns’ manager. After losing an exciting pennant race in 1922 to the Yankees, the Browns had fallen to fifth place in 1923 as Sisler’s absence was severely felt. Owner Phil Ball removed Leo Fohl as manager in mid-August and replaced him with longtime coach Jimmy Austin for the balance of the season.

Ball then hired Sisler as manager on October 21, 1923. It was a position he had turned down three years earlier, but with his playing future somewhat in doubt, he was now quite willing to take on the challenge. His contract was for one year with pay contingent upon his ability to play as well as manage. If playing was now out of the question, Sisler was content to manage only. As things played out, he was able to perform at a level well beyond the average player, but not at the level that had seen him hit .407 in 1920 and.420 in 1922.

Sisler had essentially inherited a team that came close to winning in 1922. Rick Huhn in his splendid biography The Sizzler: George Sisler, Baseball’s Forgotten Great, projected the 1924 Browns:

The regular lineup could certainly hit with the best, but in fairness no longer could be called youthful. The outfield of Jacobson, Tobin, and Williams … showed their ages to be 33, 32, and 34 respectively. Sis was now 31, [Catcher Hank] Severeid 33, and shortstop Wally Gerber 32. Only 24-year-old second baseman Marty McManus was a youngster who played regularly from the start. Gene Robertson, 25, eventually took over at third base … the pitching … was essentially unchanged ... Shocker was around ... and in 1923 he had once again delivered 20 wins.

The Browns assembled for spring training in Mobile, Alabama, for the third straight year in 1924, and Sisler soon resumed his comfort zone at the plate. By the time the team reached St. Louis, he was hitting .324 in 16 exhibition games. After a slow start, the Browns were 16-11 and in second place on May 22 while the new player-manager was hitting at a .315 clip by mid-June. That would be as high as they would go, but they were still in the race in late August only three and a half games from first despite being lodged in fourth place. It would be where they would finish the season as a devastating 1-9 run at season’s end left them at 74-78, 17½ games from the top as the Yankees took the American League flag. A highlight of the season was Urban Shocker’s ironman performance on September 6, when he pitched two complete-game 6-2 victories over the White Sox. One wonders who was doing the pitch count that day.

Sisler himself finished with a .305 average with nine home runs and 74 RBI. These would be great numbers for almost anyone but Sisler. He was no longer the force to be reckoned with that he once was, and Bob Shawkey, Yankee pitcher, in Donald Honig’s The Greatest First Baseman of All Time, told why:

When he was up at the plate, he could watch you for only so long, and then he’d have to look down to get his eyes focused again. So, we’d keep him waiting up there until he’d have to look down and then pitch. He was never the same hitter again after that.

True, but he would nonetheless raise his average to close to .350 in 1925 while guiding the Browns to a third-place finish behind the eventual pennant winning Washington Nationals (Senators). Sisler would be the first major league player to make the cover of Time magazine when he appeared there in the March 30 issue. The magazine asked: “Will he, fans wonder, regain his former prowess?” The above number would seem to indicate an answer of: “Yes, but not quite.”

The 1925 Browns changed spring training sites, moving from Mobile to Tarpon Springs, Florida. The new site would enable them to be closer to major league opposition for exhibition play. The team had made a major trade over the off-season, giving up the veteran Shocker to the Yankees for right handers Joe Bush and Milt Gaston and lefty Joe Giard. While Bush was past his prime, the three acquisitions would win 39 games between them. Notable newcomers among the position players were outfielder Harry Rice, shortstop Bobby LaMotte, and catchers Leo Dixon and Pinky Hargrave.

The Browns opened the season at home against Cleveland, and Sisler sent Bush to the mound. The initial results were not encouraging as the Indians scored 12 runs in the eighth inning on their way to a 21-14 victory. In the history of the American League in only one other game have both teams scored as many runs. Sisler himself committed a career high four errors, and the team then dropped the next three games before finally beating the White Sox. But better things were ahead for both the team and their playing manager.

On May 21 with the team in fifth place, Sisler failed to hit in a game for the first time since the season opened. The 34-game hitting streak still stands as an American League record from the start of a season. By June 5 the club was in the first division at fourth place with a 24-24 record.

Weak pitching would plague the 1925 Browns, and by the time the Yankees arrived at Sportsman’s Park for a series on July 8 they had slipped back to fifth at 38-40. That still put them two places above the Evil Empire, which was suffering through a rare bad year. For New York, the season was characterized by Babe Ruth’s “tummy ache heard ’round the world” in spring training and his subsequent $5,000 fine for missing two games in a later series with the Browns. Still, there was optimism in New York as the second half of the season began. Harry Cross, New York Times, July 6, 1925:

These Yanks know as well as anyone else that they belong in the first division. … As the Yankee excursion whirled from Washington to this city [St. Louis] there was a general and hopeful feeling among the players that the second half of the season of 1925 could not possibly be as depressing for them as the first.

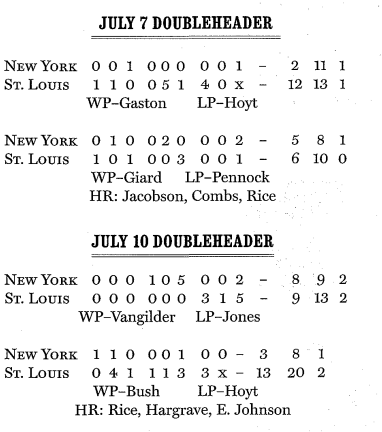

But it would be. Sisler started the two former Yankee hurlers in the opening doubleheader on July 7. Gaston limited the visitors to two runs while scattering 11 hits in the opener. The Browns got five runs in the fifth and four in the seventh en route to a 12-2 romp, which featured triples by the manager and Jacobson among 13 hits. Ruth went l-for-4 and sat out the second game.

Joe Giard would have only one noteworthy major league season, and 1925 was his brief place in the sun. He would gain one of his 10 wins in the nightcap, matching Gaston’s complete-game effort. Jacobson’s three-run homer in the sixth inning put the Browns ahead 5-3 until Earl Combs tied it with a two run blast in the top of the ninth. The home team would have the last laugh, however, as Harry Rice pounced on reliever Herb Pennock’s 1-0 delivery for the winning home run in the last of the ninth to make the final 6-5.

The kind of heat for which St. Louis is famous came out in full force for the single game on July 8. Harry Cross, July 9, 1925: “It was so hot in the ballpark that the peanuts were badly burned before the fans could eat them. Ice has taken on the same value as uncut diamonds…. When one mentions the fact to a native St. Louisan that it is hot, they come right back with that old one about, ‘Oh, this isn’t hot. We don’t take off our coats until the sun starts to blister the paint on the houses.”‘ The weather was apparently to the visitors’ liking. Ruth put New York ahead 2-0 in the top of the third with a two-run shot off Dixie Davis, and the visitors were never headed. The Yankees were aided by three St. Louis errors, two by third baseman Gene Robertson, and led 6-2 in the eighth before the home team added two to make it close at 6-4.

Cooling rains came to St. Louis the next day and they worked very well in the Browns’ favor. Trailing 8-5 in the top of the fourth, Harry Cross, July 10, 1925, describes what happened:

In the third it became as dark as doomsday, accompanied by a sky full of lightning flashes and claps of thunder which shook the grandstand. The rainfall in sheets…. There have been rainstorms and rainstorms, but never one like this. There were perhaps 6,000 fans in the stands and not one escaped a drenching…. The storm followed a day of stifling humidity and roasting heat.

The rains allowed Joe Bush to escape another bad effort. His former teammates had quickly knocked him out in the first inning with a seven-run barrage, but the Browns managed to claw their way back before the downpour came to wipe out everyone’s efforts, including Sisler’s two-run homer in the bottom of the first.

The teams resumed play on July 10 with a doubleheader, and Yankee manager Miller Huggins sent Shocker against his former team in the first game. He was superb for six innings as the visitors built up a 6-0 lead. The Browns then sent their old teammate to the showers in the seventh with three runs and then added another in the eighth. New York seemingly put the game out of reach with two in the ninth to provide an 8-4 lead. But Bob Shawkey, who had relieved Shocker, couldn’t live with success. Giving up three runs, he was succeeded by Sad Sam Jones, who then gave way to Herb Pennock, who had lost game two of the July 7 doubleheader. Hanging on to an 8-7 lead with Harry Rice at third and Bobby LaMotte on second, Pennock literally threw the game away. As L.A. McMaster wrote in the July 10, 1925, St. Louis Post Dispatch:

Sisler laid down a perfect bunt for a safe hit. The ball was near the third-base line and Pennock was the only one who could get near it. The pitcher finally picked up the sphere and trying vainly for Sisler at first, threw to the right field pavilion. Rice and LaMotte crossed the plate and the contest was over.

The second game proved to be another version of the first game of the July 7 doubleheader. Sisler finally got a good nine-inning effort from Joe Bush, as the Brainerd, Minnesota, native gave his former team only three runs on eight hits while the Browns scored in every inning but the first. When the game was called after the eighth because of darkness, the home team had romped to a 13-3 victory. Trailing 2-0 after an inning and a half, two two-run home runs by Pinky Hargrave and Harry Rice set the tone for the rest of the game, which featured three-run innings for the Browns in the sixth and seventh. Yankee starter Waite Hoyt lost his second game of the five game series.

Sisler had managed his team to victories in four of the five games, and New York would depart still in seventh place, a position they would find themselves in at season’s end. The teams would split the season series at 11-11, only one of nine occasions over the Browns’ 52-year history when they either broke even or won the season series with New York. On only five of those occasions did they actually win the series. 1925 would find Gorgeous George or the Sizzler, take your nickname, finishing with the best mark of his three-year run as manager. On the way there, he would put together another hitting streak, 22 games, and suffer the passing of his mother on July 27.

By late August the team was in fourth place at 66-59. In September they compiled a 16-11 mark, which would put them in third place at season’s end, 15 games behind pennant-winning Washington. In the second game of a season-ending doubleheader with Detroit, Sisler held the Tigers scoreless in a two inning relief stint. Like Ruth, Sisler had first started his career as a pitcher.

As a player Sisler would finish with his best post eye problem year with a .345 average, 224 hits, 12 home runs, and 105 RBI. Ever the perfectionist, it left him with little sense of accomplishment. Tom Meany, in Baseball’s Greatest Hitters, quotes him: “Oh, I know I hit .345 and got 228 [sic] hits in 1925, but that never gave me much satisfaction. That wasn’t what I call real good hitting.”

Not much satisfaction to the man described as “the perfect player,” but great satisfaction to St. Louis fans, particularly in this five-game set in early July 1925 when Sisler hit .524 (11-21) as the Browns took four of the games.

ROGER GODIN lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and is the team curator for the Minnesota Wild. He is the author of The 1922 St. Louis Browns: The Best of the American League’s Worst.

Sources

Huhn, Rick. The Sizzler: George Sisler, Baseball’s Forgotten Great. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2004.

Meany, Tom. Baseball’s Greatest Hitters. New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1950.

New York Times, July 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 1925.

Sabol, Ken. Babe Ruth & The American Dream. New York: Balantine, 1974.

St. Louis Post Dispatch, July 8, 11, 1925.

St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 9, 1925.

The Baseball Encyclopedia, 10th ed. New York: McMillan, 1996.