Slide, Kelly, Slide

This article was written by Joanne Hulbert

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

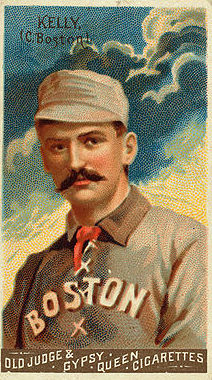

About 3,000 people were present at the Brotherhood Base Ball Grounds when the championship pennant for 1890 was presented to the Boston Club. Colonel Charles H. Taylor made the presentation speech, complimenting the team upon the high standard of their work during the season. Mike Kelly received the pennant, made no set speech, and immediately hoisted the banner while the band played the music of “Slide, Kelly, Slide.” A five-inning game was played by the champions and the New York Club. Boston featured all three of their batteries, while O’Day and William Brown pitched and caught for New York throughout the game.1

About 3,000 people were present at the Brotherhood Base Ball Grounds when the championship pennant for 1890 was presented to the Boston Club. Colonel Charles H. Taylor made the presentation speech, complimenting the team upon the high standard of their work during the season. Mike Kelly received the pennant, made no set speech, and immediately hoisted the banner while the band played the music of “Slide, Kelly, Slide.” A five-inning game was played by the champions and the New York Club. Boston featured all three of their batteries, while O’Day and William Brown pitched and caught for New York throughout the game.1

I played a game of base-ball, I belong to Casey’s nine,

The crowd was feeling jolly, and the weather it was fine;

A nobler lot of players I think were never found,

When the omnibuses landed that day upon the ground.

The game was quickly started, they sent me to the bat,

I made two strikes, says Casey, “What are you striking at?”

I made the third, the catcher muffed and to the ground it fell,

I run like a divil to first base, when the gang began to yell:2

Mike “King” Kelly need not say any words to the assembled audience. The song said it all for him. A song that despite its seemingly admonishing tone reflected the regard the cranks held for this player who embodied all the good – and sometimes the less reputable side – of the national pastime, and he had captured the affection of another man who owned the Kelly name.

(Chorus)

Slide, Kelly, slide, your running’s a disgrace,

Slide, Kelly, slide, stay there, hold your base;

If some one doesn’t steal you and your batting doesn’t fail you,

They’ll take you to Australia, slide, Kelly, slide.3

How the song came to be written brings up the history of another Kelly – James W. Kelly, an Irish comedian and author of popular songs during the last decades of the nineteenth century. He was born in Philadelphia in 1854 and was called “a mirth provoker.”4 He was described as “having a wonderfully expressive face, a musical voice of limited range, which he knew how to use to the best advantage, and that mother wit, said to be one of the distinguishing traits of the Celtic race, from which he sprang. Though not a musician, he had a natural ear for melody, and composed the airs of all his own songs.”5 Parodies were his most reliable formula, and he carried over themes and cadences that ended up in other of his renditions. Why he was so smitten with King Kelly could be chalked up to being his namesake, or King Kelly deserved a stirring ballad to complement his outsized image on the baseball diamond. King Kelly needed no introduction to the cranks across the country.

“Slide, Kelly, Slide” immediately became a favorite on the vaudeville circuit and was also a financial gold mine for the publisher, Frank Harding, who purchased James Kelly’s interest in it. Harding published 27,000 copies of the words and music, and Henry Wehman, the Park Row publisher who secured the right to print the words, sold 40,000 copies of it. James Kelly probably made more money out of this composition than any of his other popular songs.6 At the height of his career, James W. Kelly was the highest-paid performer on the variety stage, receiving as much as $400 per week. The Boston Vaudeville Club paid him regularly $100 for a single performance. Unfortunately he did not possess many frugal habits – “being a hail fellow well met, his large earnings were dissipated with the rapidity with which they were made.”7 He died on June 26, 1896, at his mother’s home in New York City of an attack of acute gastritis at the age of 42.

’Twas in the second inning they called me in, I think,

To take the catcher’s place while he went to get a drink;

But something was the matter, sure I couldn’t see the ball,

And the second one that came I broke my muzzle, nose and all.

The crowd up in the grand stand they yelled with all their might;

I ran towards the club house, I thought there was a fight;

’Twas the most unpleasant feeling I ever felt before,

I knew they had me rattled when the gang began to roar:8(Chorus)

James Kelly wrote 15 comic songs. His most popular along with “Slide, Kelly, Slide” were “Come Down, Mrs. Flynn” and “Throw Him Down, McCloskey,” a ballad that celebrated a popular boxer of the time and the chorus of this song hinted at the rhythm and cadence of his most famous song:

“Throw him down, McCloskey,” was to be his battle cry –

Throw him down, McCloskey, you can lick him if you try,

And future generations, with wonder and delight,

Will read on histr’y’s pages of the great McCloskey fight.9

The tragic demise of King Kelly in 1894 and also that of James W. Kelly in 1896 did not spell the end of the song. The cranks kept up the chorus “Slide, Kelly, slide!” at baseball games. Soon the phrase found its way into the American slang dictionary – another addition bequeathed by baseball. The phrase turned up in odd and interesting places. An apocryphal tale relates that as King Kelly was carried into a Boston hospital on a stretcher that toppled over, tossing him to the ground, he weakly lamented, “This is my last slide.”10

Ultimately, any person with the name Kelly was fair game to have the phrase used to their advantage. Any report of icy sidewalks or any warning of uncertain footedness conjured up the warning: ‘Slide, Kelly, slide!” Fred C. Kelly, a Cleveland Plain Dealer columnist, wrote about the burden the name Kelly placed upon him, and how it soured him on playing baseball as everyone insisted he “slide!” – when he didn’t want to.11

But what was it that connected Mike “King” Kelly with the “slide”? The story and the legend of Mike Kelly lived on long after his death. James J. Corbett, in his syndicated column “In Corbett’s Corner,” reminisced in 1919 about Kelly and his connection to the slide. Corbett called it a stunt, that Kelly had perfected the head-first slide, a tactic that was considered either brave or foolhardy, and was discouraged by managers as potentially injurious.12

In 1907 at a preseason meeting in New York City, a new rule was adopted that if one baserunner passed another in an attempt to score while the other was being “tagged” out, the runner who passed would be declared out – all this thanks to an incident made famous by Mike Kelly. The new rule was calculated to prevent such stunts as the world-renowned slide pulled off by Kelly when he was a member of the Chicago team during a game in Boston in 1885.

In 1907 at a preseason meeting in New York City, a new rule was adopted that if one baserunner passed another in an attempt to score while the other was being “tagged” out, the runner who passed would be declared out – all this thanks to an incident made famous by Mike Kelly. The new rule was calculated to prevent such stunts as the world-renowned slide pulled off by Kelly when he was a member of the Chicago team during a game in Boston in 1885.

“It happened in the last half of the ninth inning, when the score stood 1 to 0 against Chicago. Kelly was on first base and Ed Williamson was on second, and Anson knocked a fly ball out into right field. At the instant the fielder caught the ball both Kelly and Williamson made a dash for second and third. The ball was simply returned to the second baseman, but Kelly slid in and beat it by a hair. When Kelly arose from the ground and saw Billy Sunday at bat, he grabbed his arm, and pretending to be writhing in agony, he signaled to the umpire to call time. Then he called to Ed Williamson to come and pull his arm. While Ed was doing so, Kelly whispered to him as follows: “Say, Ed, when the pitcher throws the ball in, I’m going to start for third. This will draw the ball down to catch me, and then you make a dash for the plate and I’ll be right behind you. By the time you get near the plate the catcher will be waiting for you with the ball, but get as near as you can to the plate, then open your legs wide and I will try to slide in.”13

At the appointed time Kelly dashed for third. The ball was shot down to that base, and then Ed made for home, while the third baseman sent the ball back to the catcher. Kelly by this time had rounded third and was right behind Williamson, for whom the catcher was waiting with outstretched arms. When within a few feet of the plate, Williamson halted, suddenly spread his legs wide apart, and as the catcher jumped forward to tag Ed, Kelly slid between Williamson’s legs and had his fingers on the plate before the catcher knew what had happened. Chicago made another run in the 10th inning, and this won the game.14

Kelly turned to the crowd and shouted: “It’s all over! The game’s won! You can’t get it back! Open the gates and go home!”15 He laughed, and at first the crowd was enraged and protested he didn’t touch third base. Sam Wise yelled, “He cut the bag by 5 yards!” But then a great cheer arose from the crowd of 10,000 for the trickiest ballplayer who ever walked the diamond. This trick was original with Kelly, and many players have since tried it.16

As baseball stories go, the tale of Kelly’s slide spread across the land. The feat quickly became material for the song, as no one had ever heard of such a ploy to score a run, but James W. Kelly saw a lucrative opportunity by exploiting that move and the phrase and song “Slide, Kelly, Slide!” live on forever in baseball history.

They sent me out to centre-field, I didn’t want to go,

The way my nose was swelling up, I must have been a show;

They said on me depended victory or defeat,

If a blind man was to look on us, he’d know that we were beat.

Sixty-four to nothing was the score when we got done,

And everybody there but me said they had lots of fun;

The news got home ahead of me, they heard I was knocked out,

The neighbors carried me in the house, and then began to shout:17Slide, Kelly, slide, your running’s a disgrace,

Slide, Kelly, slide, stay there, hold your base;

If some one doesn’t steal you and your batting doesn’t fail you,

They’ll take you to Australia, slide, Kelly, slide.18

JOANNE HULBERT, co-chair of the Boston Chapter and of SABR’s Baseball Arts Committee, spends long hours gathering baseball poetry and other unique history related to baseball. A resident of Mudville, a village of Holliston, Massachusetts she proudly and unabashedly admits to having been nurtured on countless Saturday night suppers that included Boston Baked Beans, cuisine that eminently prepared her to take on a bit of Beaneater history.

Notes

1 “Mike Kelly Receives the Pennant,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 12, 1890: 3.

2 “Slide, Kelly, Slide.” Copyright, 1889, Frank Harding. Words and Music by J.W. Kelly.

3 Ibid.

4 “Exit J.W. Kelly, the Famous Rolling Mill-Man Responds to the Final Call,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 27, 1896: 1.

5 Ibid.

6 “John W. Kelly’s Songs,” Duluth News-Tribune, July 7, 1896: 6.

7 “Exit J.W. Kelly,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 12, 1890: 3.

8 “Slide, Kelly, Slide.”

9 “John W. Kelly’s Songs.”

10 “Greatest of All,” Oregonian (Portland), December 29, 1907: 7.

11 Fred C. Kelly, “The Burden of a Name,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 23, 1911: 4.

12 James J. Corbett, “In Corbett’s Corner,” Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, January 19, 1919: 10.

13 “Runners Did Not Pass Each Other,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 5, 1907: 16.

14 “Kelly’s Slide Home,” Dallas Morning News, March 31, 1907.

15 “How Kelly Cut Third,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 18, 1897: 18.

16 Ibid.

17 “Slide, Kelly, Slide.”

18 Ibid.