Switch-Hit Home Runs 1920-60

This article was written by Cort Vitty

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

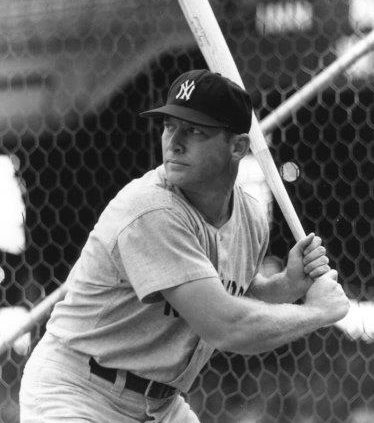

Mickey Mantle was turned into a switch hitter when he was “barely old enough to walk.” He remains the only switch-hitter in the history of the game to earn Triple Crown honors. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Mickey Mantle posted a .353 batting average, slammed 52 homers, and drove in 130 runs in 1956. It was a breakout season for “The Mick” and a performance warranting American League Triple Crown honors. Mantle’s remarkable season called attention to switch-hitting, affirmed his status as the premier switch-hitter in the game, and established a standard for future hitters with power from both sides of the plate.

Switch-hitting dates back to the earliest days of the game, when singles produced runs and homers were a rare occurrence. Good players found hitting from both sides provided an advantage against sidearm deliveries and tricky pitches, but in the early part of the twentieth century contributed little power. As Robert McConnell noted in the 1979 issue of the SABR Baseball Research Journal, “Prior to Mantle’s time, switch-hitters made little contribution in the home run, slugging and RBI departments.”1 Looking at 1920 as the first season after the Deadball era, the top career switch-hitting home run hitters through that year are listed below, career totals in parentheses:

| HR | BA | OPS | SLG | Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| George Davis | 72 | .295 | .767 | .405 | 1890-1909 |

| Walt Wilmot | 58 | .276 | .741 | .404 | 1888-1909 |

| Duke Farrell | 51 | .277 | .723 | .385 | 1888-1905 |

| Tom Daly | 49 | .278 | .746 | .386 | 1884-1903 |

| John Anderson | 49 | .290 | .734 | .405 | 1894-1908 |

| Tommy Tucker | 42 | .290 | .737 | .373 | 1887-1899 |

| Dan McGann | 42 | .284 | .744 | .381 | 1896-1908 |

| Candy LaChance | 39 | .280 | .697 | .379 | 1893-1905 |

| Cliff Carroll | 31 | .251 | .649 | .329 | 1882-1893 |

| Max Carey | 31 | .275 | .713 | .364 | 1910-1929 |

The arrival of Babe Ruth changed everything. As Bill James writes, “The fans were galvanized by the Ruth phenomenon; his coming was unquestionably the biggest news story that baseball ever had.”2 Coinciding with the emergence of Ruth and the elimination of the spitball and other trick pitches, excited fans delighted in watching runs scored in bunches. Owners were happy to comply, while filling seats to capacity. Hitters started to copy the Ruthian swing, but few had significant power from both sides of the plate.

Indiana native Max Carey enjoyed a fine career as a switch-hitter with the Pittsburgh Pirates and Brooklyn Robins. His major league tenure (1910–29) bridged the transition from deadball to the modern era. Max reached double-digits in 1922, poking 10 home runs and commented: “Naturally, I was a right-handed hitter. But I forced myself to learn left-handed batting. Even now I can hit the ball harder right-handed, but the percentage in favor of the left-handed batter is too great to be ignored, especially where the batter wishes to capitalize his speed as I have done.”3 Carey ultimately finished his career with 70 lifetime home runs, moving him up to second on the all-time list, behind George Davis. (Frankie Frisch would surpass Carey.)

Washington, D.C. native Lu Blue served as an Army sergeant during World War I, and subsequently patrolled first base for the Tigers, Browns, White Sox, and Dodgers. Blue started switch-hitting in the minor leagues as an antidote to a prolonged slump; he enjoyed immediate success and continued to hit from both sides during his major league career. The Sporting News called the lefty thrower, “incomparable to any man in baseball as a fielding and throwing first baseman.”4 Blue’s power was sufficient enough to poke 14 home runs in 1928. Lu and his ultra-selective batting eye retired with a lifetime on-base percentage of .402. He passed away in 1958 and is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Frankie Frisch hit two homers as an All-Star, from the left side in 1933 and from the right side in 1934. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

New York native and future Hall-of-Famer Frankie Frisch segued from being a star athlete at Fordham University to signing with the New York Giants in 1919. He emerged as a prominent switch-hitter with power, hitting 12 home runs in 1923. A natural left-hand hitter, “Frisch batted cross-handed when he hit from the right-side, keeping his left hand above his right hand. Manager John McGraw worked with him, teaching fielding and sliding techniques, plus how to hold the bat properly.”5 Frisch would ultimately move on to become a player-manager with the St. Louis Cardinals, where his talented line-up included fellow switch-hitters Jack Rothrock and Ripper Collins.

The colorful Collins made his major league debut in 1931, hitting four home runs with the St. Louis Cardinals. His home run output rose to a healthy 21 dingers in 1932. By 1934, Ripper helped spark the “gashouse gang” to a world championship, by muscling an impressive 35 round trippers, tying him for the league lead with Mel Ott. Up to this point, Walt Wilmot of the Chicago Cubs was the only switch-hitter to lead the National League, smacking 13 home runs in 1890, and tying for the league lead with Oyster Burns and Mike Tiernan. Collins’s 1934 performance became the single season standard for a switch-hitter until Mantle hit 37 in 1955. Did switch-hitting help the club win the 1934 World Series? “Yes,” answered manager Frisch. “The more a team can keep its infield and outfield intact, the smoother its play is likely to be.”6

Collins was a natural left-hander; his dad taught him to hit (and throw) both left and right-handed. Ripper kept a personal collection of discarded (game used) gloves and bats; from his huge cache he routinely carried a right-handed fielder’s glove and practiced throwing right-handed. According to Collins, “Manager Frankie Frisch once considered inserting me into the lineup at third base, when he was short an infielder; I would’ve been removed as a left-handed first baseman to play as a right-handed third baseman.”7 Ripper tied and surpassed George Davis on April 27, 1935, hitting career home runs number 72 and 73 off Pirates right-hander Jim Wilson. Retiring in 1941, Rip’s 135 lifetime home runs placed him at the top of the all-time list, among career switch-hitters.

California native Buzz Arlett debuted with the Philadelphia Phillies on April 15, 1931, and proceeded to hit for a .313 batting average, with 18 round trippers. Despite those respectable numbers, his best years were spent in the Pacific Coast League and his skills were considerably diminished by the time he reached the major leagues. Originally a good hitting pitcher, Arlett won 29 games in 1920 before overuse ruined his pitching arm. The bad wing made swinging from his natural right side impossible, so Buzz was granted permission to practice hitting left-handed; he subsequently became a switch-hitting outfielder and went on to smack 432 minor league round trippers, before retiring in 1937.

Also of note in 1931 was the October 20 birth of Mickey Mantle in Spavinaw, Oklahoma. Mickey’s dad Elvin “Mutt” Mantle was a huge baseball fan and likely took notice of switch-hitters Collins and Arlett arriving on the major league scene. “My dad always believed there would be platooning some day,” Mantle said. “As a kid barely old enough to walk, Mantle was turned into a switch-hitter.”8

Frankie Frisch had the honor of hitting left/right home runs in the first two (one in each) All-Star games. On Thursday July 6, 1933, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park and batting left, Frankie victimized Alvin (General) Crowder in the sixth inning, though the National League fell, 4–2. The very next All-Star match was at the Polo Grounds in New York on July 10, 1934; this time Frisch went deep in the first inning while batting right-handed against Lefty Gomez. The American League went on to a 9–7 victory.

Versatile Augie Galan enjoyed a fine major league career spanning 1934 to 1949. As a child in California, Augie fell out of a tree and broke his right arm. Fearing retribution from his parents, he never told them about the accident. The arm didn’t heal properly and he compensated by learning to throw using his shoulder muscles. Galan ultimately slugged 100 lifetime homers and on June 25, 1937, he had the distinction of becoming the first National League player to homer from both sides of the plate in a single game. Batting lefty, the Cubs outfielder took Brooklyn’s Freddie Fitzsimmons deep in the fourth inning. Hitting right-handed against Ralph Birkofer, he homered again in the eighth. Roscoe McGowan of The New York Times noted: “Galan was the first to profit by the new fence in left field, which brings the barrier twenty feet closer to the plate. His second home run just cleared the fence, which is the first bit of construction leading toward installation of new bleachers to increase park capacity by 5,000.”9 Augie turned into solely a left-hand batter from 1943 until 1949.

In the American League, Athletics catcher Wally Schang hit lefty/righty home runs on September 8, 1916, at Shibe Park in Philadelphia against the New York Yankees. Batting left, his first homer was served by right-hander Allen Russell, while his second was hit while batting right-handed versus lefty Slim Love; this one bounced over the fence and was recorded as a homer according to 1916 rules. The incident was not publicized at the time, due to an unusual circumstance. “So much rain fell that day that reporters, assuming the game could not possibly be played, did not go to the park. For scheduling purposes, Connie Mack insisted that the game be played in a late afternoon sea of water, in front of fewer than 100 people.”10

Under modern rules, the first American Leaguer to actually muscle the ball over the fence from both sides was Johnny Lucadello of the St. Louis Browns, also while playing the Yankees. On September 16, 1940, he connected as a right-hand batter against lefty Marius Russo in the first inning; he next homered as a left-hand batter against Steve Sundra in the seventh. The Brownies went on to complete a 16–4 drubbing of the defending AL champs. Curiously, these were the only two home runs Lucadello hit all season, coming on the same day, from both sides of the plate. Johnny hit only five homers during a big league career from 1938 to 1947; albeit shortened by four prime years lost to military service during WWII.

Fayette City, Pennsylvania, native Jim Russell became the first major leaguer to hit lefty/righty homers in the same game twice in a career. Russell began switch-hitting as a youngster to compensate against his brother’s tricky curve ball. Originally a Pittsburgh Pirate, Russell moved over to the pennant-bound Boston Braves in 1948. He connected from both sides against the Chicago Cubs on June 7, 1948, going deep against LHP Dutch McCall in the fifth and again versus RHP Ralph Hamner in the seventh. Moving over to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1950, he enjoyed a second switch-hit homer day on July 26, against the St. Louis Cardinals. This time he drove one out one against lefty Harry Brecheen in the first inning, followed by taking right-hander Red Munger deep in the fifth. Russell was gone from the majors after the 1951 season; he posted a total of 67 career homers. His best single season mark was 12 homers in the last wartime season of 1945, back with the Pirates.

At the close of the 1940s, journeyman switch-hitter Roy Cullenbine had 110 career home runs, good enough to place him second to Ripper Collins on the all-time list. Roy grew up in Detroit and served as Tigers batboy in 1929–30. Invited to a tryout, he was signed by Detroit in 1933 as a right-handed hitter. In 1935, while playing for Springfield in the III league, he impetuously jumped over to the left batter’s box, during batting practice. Manager Bob Coleman watched Cullenbine launch several pitches deep into the right-field stands, and announced, “Roy from now on you’re a switch hitter.”11

During a career spanning 1938 to 1947, Cullenbine made stops with the Dodgers, Tigers, Browns, Indians, Senators, and Yankees. Weight gain greatly affected his performance, and it was the slimmer version of Cullenbine acquired by the Yankees on August 31, 1942. The move was intended to fortify the outfield when Tommy Henrich enlisted in the Coast Guard. Roy hit .364 in 21 games and helped the Yankees cop the AL pennant. The Yankees assigned him uniform number 7, possibly warming it up for a future Yankee slugger with power from both sides of the plate. Roy’s lifetime batting average was .276; however, his uncanny ability to draw 853 career walks, along with 1,072 hits, gave him an impressive on base average of .408 lifetime. Roy’s top home run total was 24 as a Detroit Tiger in 1947, his final big league season.

The 1950s saw the arrival of a speedy switch-hitting center fielder—not yet Mickey Mantle, but Sam Jethroe, a successful Negro League star with the Cleveland Buckeyes. Jethroe, along with Jackie Robinson and Marvin Williams, was given a sham tryout in April 1945, by the Boston Red Sox. Afterwards, management summarily dismissed all three as not being up to big league standards. Later in 1945, Jethroe would go on to win the Negro American League batting title, hitting .393.12

Jethroe ultimately signed with the Dodgers. Dealt to the Braves, he earned 1950 rookie-of-the-year honors at the age of 32, hitting 18 round trippers for Boston, while leading both major leagues with 35 stolen bases. Buck O’Neill of the Kansas City Monarchs played against him and recalled his incredible speed, which led appropriately to “Jet” as his nickname. “When he came to bat, the infield would have to come in a few steps or you’d never throw him out.”13 Jethroe followed up with another 18-homer season in 1951, but his offensive numbers fell off sharply in 1952 and he was gone from the majors after a short trial with the Pirates in 1954. Lifetime, “Jet” smacked 49 round trippers.

The Chicago White Sox called up Dave Philley for a cup of coffee in 1941, just before he left to serve during World War II. Returning in 1946 and up for a full season in 1947, the speedy native of Paris, Texas, became a mainstay in the Chicago White Sox outfield. Possessing a strong right throwing arm, Philley led American league outfielders in assists three times during his tenure. His career best was smacking 14 home runs for the 1950 White Sox.

Philley started switch-hitting as a youngster, when an arm injury prevented him from swinging left-handed, his natural side. By the late 1950s, his role changed from regular outfielder to pinch hitter extraordinaire. He pounded 18 hits off the bench for the Phillies in 1958, with eight hit consecutively to end the season. His streak was extended to nine when he added another pinch hit in his first appearance of 1959. He laced 24 pinch hits for the Baltimore Orioles in 1961 and ultimately posted 84 round trippers during his long career.

As a youngster in Illinois, Red Schoendienst injured his left eye repairing a fence while serving with the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps. An exercise program ultimately strengthened the injured eye, but while healing he learned to hit left-handed and became an adept switch-hitter. At the 1950 All-Star game in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, his 14th-inning home run, served up by lefty Ted Gray, and provided the margin of the 4–3 victory for the National League; it was the first extra-inning summer classic.

On July 8, 1951, Schoendienst joined the switch-hit homer club by hammering one from each side of the plate against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He connected against right-hander Ted Wilks in the sixth inning, and then hit one out served by lefthander Paul LaPalme in the seventh. His top home-run production was 15, in both 1953 and 1957. His health would again be tested due to a serious bout of tuberculosis, sidelining the star second baseman virtually all of the 1959 season.

Mantle first connected from both sides of the plate on May 13, 1955. He tied the Jim Russell mark (second time) on August 15, 1955 and on May 18, 1956, became the first major leaguer to homer from both sides of the plate for a third time. This dinger, served up by Dixie Howell of the Chicago White Sox, was career home-run number 136, placing Mantle into the top position on the all-time list, by passing Ripper Collins’ 135 round-trippers. By the end of the decade, he’d up that total of same game, switch-hit homers to seven. During the 1956 season, he became the first switch-hitter to reach the 40- and then the 50-homer plateau in a single season. Mantle remarked, “1956 was a great year, the best I ever had in baseball. I would never again duplicate that season. I finally accomplished the things people had been predicting for me, especially Casey Stengel, and I felt good about that.”14

At the start of the 1960 season, the ten players with the most career switch-hit home runs included15:

- Mickey Mantle – 280

- Ripper Collins – 135

- Roy Cullenbine – 110

- Frankie Frisch – 105

- Augie Galan – 100

- Dave Philley – 81

- Red Schoendienst – 80

- George Davis – 73

- Max Carey – 70

- Jim Russell – 67

Mantle ultimately went on to smack 536 blasts during his storied career, ending in 1968. He remains the only switch-hitter in the history of the game to earn Triple Crown honors. Lifetime, his OPS was .977, while he posted a career slugging percentage of .557. Players on the above list, still active after 1960, included both Philley and Schoendienst; each would finish their respective careers with a total of 84 home runs. Players capable of hitting with power from both sides of the plate will continue to come and go, but Mantle’s strength, talent and influence certainly remains the standard.

CORT VITTY is a native of New Jersey and a graduate of Seton Hall University. A SABR member (Bob Davids Chapter) since 1999, Vitty is a lifelong fan of the New York Yankees. His work has previously appeared in the “Baseball Research Journal,” “The National Pastime,” “Go-Go to Glory: The 1959 White Sox,” Seamheads.com and PhiladelphiaAthletics.org. Vitty resides in Maryland with his wife Mary Anne.

Sources

Allen, Lee. Hot Stove League. A.S. Barnes & Co. New York, 1955, 35.

Daley, Arthur. “The Idle First Baseman.” New York Times, January 20, 1957.

Goldstein, Richard. “Sam Jethroe is Dead at 83.” New York Times, January 19, 2001.

James, Bill. Historical Baseball Abstract. Villard Books: New York, 1988, 125.

Lane, F.C. Batting. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, 2001, 53.

Mantle, M. & Pepe, Phil. My Favorite Summer 1956. Doubleday: New York, 2001, 241.

Vincent, David. Home Run: The Definitive History. Potomac Books, Washington D.C., 2007.

The Baseball Encyclopedia. Ed. Joseph Reichler. MacMillan: New York, 1982.

The Home Run Encyclopedia. Ed. Robert McConnell & David Vincent. MacMillan: New York, 1996.

The SABR Baseball List & Record Book. Ed. Lyle Spatz. Scribner: New York 2007.

McGowan, Roscoe. “Cubs Quickly Route Fitzsimmons.” New York Times, June 26, 1937.

Shirley, Bill. “The Art of Switch-Hitting.” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1985.

Karst, Gene. “Frisch Credits Cardinals’ Success to “Turn” Batters.” The Sporting News, January 24, 1935.

Vincent, David. Home Run lists contained in this article.

Newspapers

Chicago Tribune

Los Angeles Times

The New York Times

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Websites

Baseball Almanac

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet

SABR Baseball Biography Project

Notes

1. Robert McConnell, “Mantle is Baseball’s Top Switch Hitter,” SABR Baseball Research Journal (1979): 1. ↵

2. Bill James, Historical Baseball Abstract, Villard Books: New York, 1988, 125. ↵

3. F.C. Lane, Batting, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, 2001, 53. ↵

4. The Sporting News, April 9, 1925. ↵

5. Fred Stein, “Frankie Frisch,” SABR BioProject. ↵

6. The Sporting News, January 24, 1935. ↵

7. Arthur Daley, “The Idle First Baseman,” New York Times, January 20, 1957. ↵

8. Bill Shirley, “The Art of Switch-Hitting,” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1985. ↵

9. Roscoe McGowan, “Cubs Quickly Route Fitzsimmons,” New York Times, June 26, 1937. ↵

10. Robert McConnell, “Searching Out The Switch Hitters,” SABR Baseball Research Journal (1973): 1. ↵

11. The Sporting News, September 10, 1942. ↵

12. Richard Goldstein, “Sam Jethroe Is Dead at 83,” New York Times, June 19, 2001, 21. ↵

13. Bob Ajemian, “$100,000 Jethroe May Be Flop in Outfield,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1950. ↵

14. Mickey Mantle & Phil Pepe, My Favorite Summer 1956, Doubleday: New York, 2001, 241. ↵

15. Home Run List(s) courtesy David Vincent. ↵