Ted Williams’ Year in Minneapolis

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the North Star State (Minnesota, 2012)

This article provides an in-depth look at Ted Williams and his year spent in Minneapolis.

This article provides an in-depth look at Ted Williams and his year spent in Minneapolis.Ted Williams wasn’t happy about being sent to Minneapolis. He graduated from San Diego’s Hoover High School, completed his second year with his hometown San Diego Padres, borrowed $200, and took the train cross country to Sarasota, Florida, where the Boston Red Sox held spring training in 1938.

There’s a story that Bobby Doerr told Ted, “Wait’ll you see [star first baseman Jimmie] Foxx hit.” Ted supposedly replied, “Wait’ll Foxx sees me hit!” Williams denied it in his autobiography, My Turn At Bat, but acknowledges, “I suppose it wouldn’t have been unlike me.” Ted was chagrined when he was assigned to Daytona Beach, the spring training home of the Minneapolis Millers, Boston’s top minor-league affiliate. He’d come across as brash and cocky to manager Joe Cronin and been given some riding by his fellow outfielders, and he did admit to telling clubhouse man Johnny Orlando, “Tell them, I’ll be back, and tell them I’m going to wind up making more money in this frigging game than all three of them put together.”[fn]Ted Williams, My Turn At Bat (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969), 47.Ted’s autobiography was first published in 1969. Were it published today, it’s a fair guess that we would learn the word “frigging” was sanitized.[/fn]

There’s a story that Bobby Doerr told Ted, “Wait’ll you see [star first baseman Jimmie] Foxx hit.” Ted supposedly replied, “Wait’ll Foxx sees me hit!” Williams denied it in his autobiography, My Turn At Bat, but acknowledges, “I suppose it wouldn’t have been unlike me.” Ted was chagrined when he was assigned to Daytona Beach, the spring training home of the Minneapolis Millers, Boston’s top minor-league affiliate. He’d come across as brash and cocky to manager Joe Cronin and been given some riding by his fellow outfielders, and he did admit to telling clubhouse man Johnny Orlando, “Tell them, I’ll be back, and tell them I’m going to wind up making more money in this frigging game than all three of them put together.”[fn]Ted Williams, My Turn At Bat (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969), 47.Ted’s autobiography was first published in 1969. Were it published today, it’s a fair guess that we would learn the word “frigging” was sanitized.[/fn]

Cronin was probably wise to provide another year of seasoning for “The Kid,” as Johnny Orlando dubbed Williams, and Williams admitted as much.

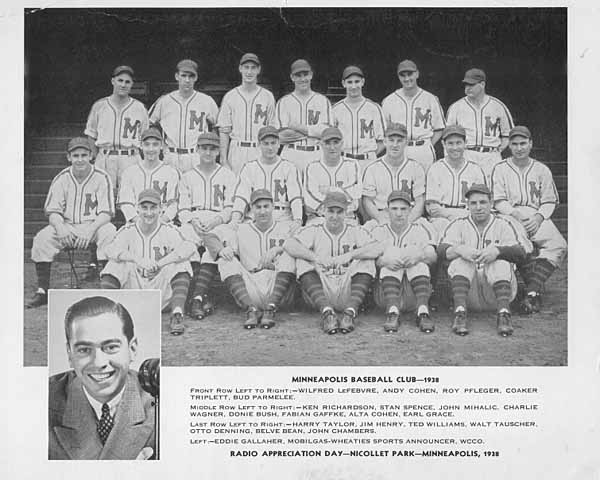

Williams played right field for the Millers and manager Donie Bush. A veteran of 16 years in the majors (1908–1923, with the Tigers and Nationals), and a big-league manager for seven seasons, Bush was nothing if not experienced. Reflecting 30 years later, Bush called him “a lovable little tiger,” but at the time Bush wasn’t so pleased with The Kid’s demeanor, reportedly telling Millers owner Mike Kelley at one point, “It’s Williams or me, one has to go.” Kelley allowed as how Williams wasn’t going, saying something along the lines of “Gee, we’d miss you, Donie”—so the choice was up to Bush.[fn]James D. Smith, in The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego, edited by Bill Nowlin (Cambridge MA: Rounder Books, 2005), 162.[/fn] The manager and his player eventually learned to work with each other. Williams was particularly pleased to have Rogers Hornsby working with the Millers as a batting instructor. They hit it off, as hitters.

“Every day I’d stay out after practice with Hornsby and maybe one or two others who wanted extra hitting. Hornsby was like any of the really great players I have known—he just couldn’t get enough of it. He was pushing fifty, then, I guess, but we’d have hitting contests and he’d be right in there, hitting one line drive after another….”[fn]Ted Williams, 53.[/fn]

Williams was impressed by one thing. Hornsby—with Cobb, one of just two men since 1901 to hit .400 more than once—never criticized Ted, a powerful pull hitter, for hitting to his strength. He never pushed Ted to hit to left field. And it was Hornsby in 1938 who taught Ted the words that became his mantra:

“Get a good ball to hit.”[fn]Ted Williams, The Science of Hitting (New York: Simon & Schuster,1970), 20.[/fn] Williams took the message to heart. He learned the strike zone cold, he refused to bite at pitches outside it, and he waited for his pitch. It is said that big-league umpires don’t give rookies the benefit of the doubt, yet when Williams reached the big leagues in 1939, he drew 107 bases on balls—setting an American League rookie record that still stands. Ted Williams led the league in walks eight times, and still today holds the record (minimum 1,000 games) for the highest walks percentage (20.64%) of any player who ever played the game.

Williams had a great year with the Millers, and it was one he enjoyed immensely from the start. Predictions as to how he might do differed. In March, he himself had declared to the Providence Bulletin’s Joe McGlone, “I’ll rattle those fences in the American Association.”[fn]Providence Bulletin, date uncertain, March 1938.[/fn] But the Boston Post’s Bill Cunningham wrote that same month, “I don’t believe this kid will ever hit half a Singer midget’s weight in a bathing suit.”[fn]Undated San Diego newspaper clipping.[/fn] Rogers Hornsby, better situated than either sportswriter, said, “He’ll be the sensation of the major leagues in three years.”[fn]Frank Haven, San Diego Sun, May 5, 1938.[/fn] The Millers opened the season with 12 road games. Williams played right field but was hitless in the first three. In the fourth game, he walked five times and was 1-for-1 at the plate. On April 21, he hit two inside-the-park home runs in Louisville.[fn]Thanks to Stew Thornley for compiling the day-by-day records of Ted Williams during the 1938 season. The records have been reproduced in The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego, pp. 165–169.[/fn]

Williams had a great year with the Millers, and it was one he enjoyed immensely from the start. Predictions as to how he might do differed. In March, he himself had declared to the Providence Bulletin’s Joe McGlone, “I’ll rattle those fences in the American Association.”[fn]Providence Bulletin, date uncertain, March 1938.[/fn] But the Boston Post’s Bill Cunningham wrote that same month, “I don’t believe this kid will ever hit half a Singer midget’s weight in a bathing suit.”[fn]Undated San Diego newspaper clipping.[/fn] Rogers Hornsby, better situated than either sportswriter, said, “He’ll be the sensation of the major leagues in three years.”[fn]Frank Haven, San Diego Sun, May 5, 1938.[/fn] The Millers opened the season with 12 road games. Williams played right field but was hitless in the first three. In the fourth game, he walked five times and was 1-for-1 at the plate. On April 21, he hit two inside-the-park home runs in Louisville.[fn]Thanks to Stew Thornley for compiling the day-by-day records of Ted Williams during the 1938 season. The records have been reproduced in The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego, pp. 165–169.[/fn]

The team played its first home game at Nicollet Park on April 29. Williams had a 3-for-4 day with two singles and a long home run that exited the park and, according to Minneapolis Tribune writer George A. Barton, “landed on the roof of a building on the far side of Nicollet Avenue.”[fn]George A. Barton, Minneapolis Tribune game account “Williams, Galvin, Parmelee Shine in the Nicollet Opener.”[/fn]

Dick Cullum wrote in the Minneapolis Journal:

There was not a fan in the park who did not form an immediate attachment to gangling Ted. He is as loose as red flannels on a clothes line but as beautifully coordinated as a fine watch when he tenses for action. He is six feet and several inches of athlete and the same number of feet and inches in likeable boyishness…You see a lot of players you THINK will make the big league grade. You accord them a good chance; but once in a long while you have one quick glance of a natural and you KNOW he will make it, and not as just an average big leaguer, but as a star. That would be Ted Williams. He’s a dead mortal cinch.[fn]Dick Cullum, Minneapolis Journal, April 30, 1938.[/fn]

The young Williams was a challenge, though. He’d often be spotted out in right field, taking cuts with an imaginary bat rather than focusing on defensive positioning. As early as May 5, Frank Haven wrote in the San Diego Sun that Ted had already been nominated “the screwball king of the American Association.”[fn]Frank Haven, op. cit.[/fn] Williams, meanwhile, was bragging about what a good pitcher he’d been in high school, and maybe betraying a little homesickness as well.

Donie Bush’s influence could only go so far, it seemed. There were routine fly balls Williams failed to catch, his mind seemingly elsewhere, and others he should have run out but did not—including a couple during spring training that he thought were foul. By the time he saw they were fair, the opposing outfielder earned an assist throwing him out at first base.[fn]According to an unidentified clipping from the Kansas City Journal-Post.[/fn]

Get him in the batter’s box, though, and it was a different matter. On April 21, at Louisville, he hit two home runs off Jack Tising—and they were said to have been the two longest home runs in American Association history, the first one 425 feet and the second reportedly traveling 512 feet.[fn]George Barton, Minneapolis Tribune, April 22, 1938.[/fn] He enjoyed a 21-game hitting streak that ran from May 30 (when he put a ball onto the roof of the St. Paul Coliseum) through June 19. By that time, he’d already hit 21 homers, almost twice as many as the league’s number two slugger. And a Chicago sportswriter noted that before the season was two months old, Williams had already hit at least one homer in every park in the league.[fn]Francis J. Powers, Chicago Daily News, June 20, 1938.[/fn]

Ted Williams was drawing fans to Nicollet, and he was beginning to draw raves with his fielding as well. For instance, Frank Haven wrote in late June, “He has polished his seemingly awkward, gangling fielding style to the point of near perfection, coming with ‘impossible’ stops and catches, as well as bullet-like throws from the outfield.”[fn]San Diego Sun, June 23, 1938.[/fn]

At midseason, Ted Williams and Indianapolis pitcher Vance Page were the only two unanimous choices for the American Association All-Star team.

On August 3, after driving in four runs off Bill Zuber, Ted was beaned and taken out of the game. The RBIs brought him to 102 on the season. He missed one game, and it rained the next day, but he was back on August 6 at Kansas City with a double and home run number 33, and four more runs batted in. An unidentified clipping from the Kansas City Journal-Post said he’d been called “Peter Pan” in spring training. Now he’d established himself. Against visiting Toledo in late August, he was walked intentionally five times in two games (after he’d driven in five runs in the first game of the set, his 41st home run “clearing the buildings on the far side of Nicollet Avenue.”)[fn]George A. Barton, “Kels Thump Hens, 15–11, in Bat Spree, Minneapolis Tribune.[/fn]

By the time the year was over, Ted Williams had won the Triple Crown in the American Association, with a batting average of .366, 43 home runs, and 142 runs batted in. He’d also hit 30 doubles and 9 triples. He drew 114 bases on balls.

There seemed no question but that Williams had earned promotion to the big leagues, and the Red Sox didn’t hesitate to clear the decks for him, trading away right-fielder Ben Chapman in December. Ted truly enjoyed his time with the Millers, though, and had even declared late in the season, “I want to stay right here in Minneapolis with the Millers, for another year at least. I’m not ready for the major leagues. Another year under Donie Bush will do me a lot of good. I’m young yet. I figure that if a fellow gets to the majors when he’s 21 or 22, that’s time enough. He’s got a better chance of sticking if he takes his time getting there. I don’t want to be rushed. I’ve got plenty to learn and I’ve learned plenty under Donie this year. Maybe one more year and I’ll be ready.”[fn]Unidentified news clipping.[/fn]

Was Williams ready? All he did when he got to Boston was set two rookie records that have still never been matched. He showed plate discipline, walking 107 times, and driving in 145 runs. The 145 RBIs led the American League in 1939, 19 more than second-place Joe DiMaggio and 17 more than National League leader Frank McCormick. His 344 total bases also led the league.

And after the 1939 season, Ted chose to spend the winter in Minnesota. As Jim Smith wrote, “Ted took a $5 room at the King Cole Hotel in downtown Minneapolis, traveled west to hunt mallards, north to fish for walleyes at Lake Mille Lacs, out to the city park rinks to learn ice skating, and enjoyed the heated hotel pool as well…He also began courting the daughter of a hunting guide from Princeton, Minnesota, Doris Soule, who a few years later (during World War II duty), would become his wife.[fn]James D. Smith, 164.[/fn]

BILL NOWLIN has been Vice President of SABR since 2004 and is frequently author and editor of various SABR publications, with over 250 biographies contributed to the SABR BioProject. He has written several books on Ted Williams, and many more on the Boston Red Sox.