That Was Quick!

This article was written by Wynn Montgomery

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

The average time required to play a major-league baseball game continues to hover just under three hours; the average game in 2009 took two hours and 55.4 minutes. However, games taking longer than that average are becoming more common—especially in the postseason, when the average grows to 3:36.6. In 2009, only one of the 30 postseason games was completed in less than three hours.1 Long gone are the days when Atlanta fans could see Greg Maddux regularly finish off opponents in less than two and a half hours and sometimes even faster. During his time in Atlanta, Maddux pitched in at least one game every season that ended in 2:16 or less, and on August 20, 1995, he beat the St. Louis Cardinals 1–0 in an hour and 50 minutes.

Despite his well-deserved reputation for efficiency, however, Maddux never came close to matching the efforts of an earlier Atlanta moundsman and his teammates. That last word is the key—because playing a game quickly is a team effort. In truth, it is a twoteam effort; both teams must consciously work toward a timely conclusion.

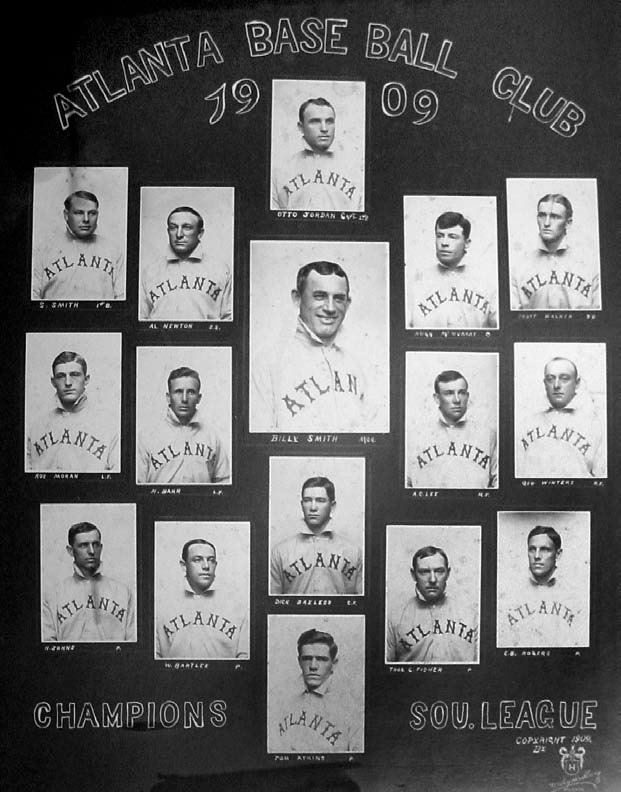

On Saturday afternoon, September 17, 1910, at Ponce de Leon Park, the Atlanta Crackers and the Mobile Sea Gulls demonstrated how quickly a baseball game can be played. Newspaper accounts of that game do not discuss the players’ motives, but we know that the game was the season finale for each team, both of which were out of contention for the Southern League crown. The New Orleans Pelicans, led by 20-year-old Shoeless Joe Jackson (who was in his third and final year of tearing up the minor leagues),2 had long since clinched the pennant. Atlanta was in third place, three games behind second-place Birmingham and comfortably ahead of Chattanooga, and sixth-place Mobile was one game behind Nashville. Atlanta’s standing could not change with a single victory or loss; Mobile had no hope of escaping the second division.

On Saturday afternoon, September 17, 1910, at Ponce de Leon Park, the Atlanta Crackers and the Mobile Sea Gulls demonstrated how quickly a baseball game can be played. Newspaper accounts of that game do not discuss the players’ motives, but we know that the game was the season finale for each team, both of which were out of contention for the Southern League crown. The New Orleans Pelicans, led by 20-year-old Shoeless Joe Jackson (who was in his third and final year of tearing up the minor leagues),2 had long since clinched the pennant. Atlanta was in third place, three games behind second-place Birmingham and comfortably ahead of Chattanooga, and sixth-place Mobile was one game behind Nashville. Atlanta’s standing could not change with a single victory or loss; Mobile had no hope of escaping the second division.

Perhaps the players simply wanted to break the existing record for rapidness—a 44-minute game played by Atlanta and the Shreveport Pirates on September 24, 1904.3 Perhaps some players had big plans for Saturday night. Perhaps some had a train to catch; it is true that many of them left immediately after the game.4 Perhaps a wager was involved—or is it mere coincidence that on that same day two teams in the same league played a nine-inning 6–3 game in only 42 minutes?5 Whatever their motivation, the two teams completed the game in only 32 minutes, setting a new record for “the fastest nine innings ever played in the organized baseball world.”6 The game received coast-to-coast attention, from the New York Times and the Washington Post to the Oakland (Calif.) Tribune. It even made the front page of the Nevada State Journal.7

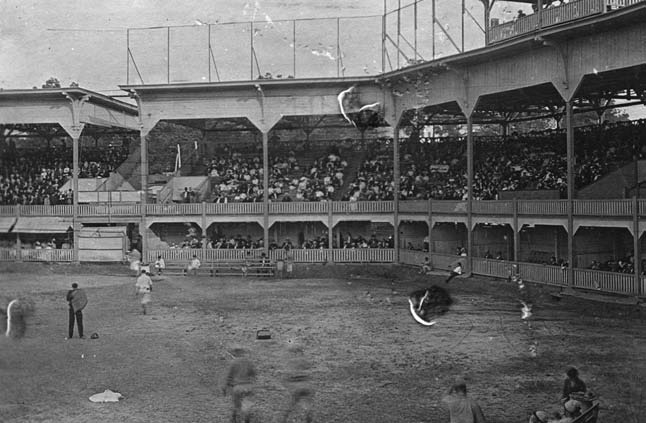

According to the New York Times, both teams ran on and off the field Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park in 1910, site of the fastest baseball game ever played. between innings. Batters even “came to bat on the run” and typically swung at the first pitch they saw—and usually hit it.8 They mostly hit grounders, allowing the fielders to record 35 assists, including nine by the pitchers.

Both pitchers—Atlanta’s Hank Griffin, a 23-year-old Texan with a .500 record, and 29-year-old “Big Bill” Chappelle, whose 18 wins made him one of Mobile’s aces—“pitched excellent games . . . and despite the terrific pace, each was as steady as the old clock in the belfry, and that’s some steady.”9 The batters’ aggressiveness minimized strikeouts (Griffin recorded the game’s only one) and walks (one by Chappelle). The defense contributed “some sensational stops and throws as well as some clutch catches by the outfielders.”10

The defensive gem of the day came in the second inning, when Mobile turned an unusual (9–3–2) triple play. After Pete Lister and Scott Walker singled to put runners on first and third, John Berkel hit a fly to right field, where Julius Watson made the catch and then doubled Walker at first base. Lister tried to score on the play, but first sacker Harry Swacina gunned him down at the plate.

Both pitchers worked “like demented steam engines,”11 and each limited his opponents to five hits to ensure a lowscoring contest. Atlanta took the lead in the bottom of the first inning. Dick Bayless led off with a double to center (or, as described by the Atlanta Journal, “Don Ricardo Bayless slammed one to the middle meadow for the keystone sack”). He then moved to third on an infield out. After another out, Atlanta’s leading hitter12 Pat Flaherty drew a walk as “four punk ones floated past.” Bayless then scored on a perfectly executed “double Raffles” (a double steal).13

Both pitchers worked “like demented steam engines,”11 and each limited his opponents to five hits to ensure a lowscoring contest. Atlanta took the lead in the bottom of the first inning. Dick Bayless led off with a double to center (or, as described by the Atlanta Journal, “Don Ricardo Bayless slammed one to the middle meadow for the keystone sack”). He then moved to third on an infield out. After another out, Atlanta’s leading hitter12 Pat Flaherty drew a walk as “four punk ones floated past.” Bayless then scored on a perfectly executed “double Raffles” (a double steal).13

That lead held up until the top of the sixth inning, when Mobile’s Charlie Seitz, who had started the season with Atlanta, tripled and scored on a wild pitch as “Griffin tried to knock a hole in the pressbox with one of his fast ones.”14

The Gulls scored the winning run in the ninth when Howard Murphy sandwiched a single between two flyouts and then “burglarized the second story [i.e., stole second]. Wagner was then so ungentlemanly as to swat the sphere to the left garden for one base, and Murphy meandered home.”15

Chappelle retired the Crackers in order in the ninth to nail down a 2–1 victory. The teams had given the fans an exciting game with a bit of everything (except a home run) and had set a still unequalled (and probably unapproachable) benchmark for baseball brevity16 by playing a nine-inning game in less time than most teams now take to complete two frames. Each plate appearance took an average of approximately 30 seconds;17 watching the game must have been akin to a preview of the frantic pace of the “Keystone Kops” movie chase scenes that became popular a few years later. The Atlanta Journal, whose coverage of the game contained so much flowery language throughout, became the epitome of understatement, saying simply, “viewed from every angle, the game was a hummer.”18

THE BOX SCORE (Atlanta Journal, September 18, 1910)*

|

MOBILE |

AB |

R |

H |

PO |

A |

E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Charlie Seitz, 2b |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

|

Joe Berger, ss |

4 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

|

Howard Murphy, lf |

4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Harry (Swats) Swacina, 1b |

4 |

0 |

0 |

17 |

1 |

0 |

|

Otto Wagner, cf |

4 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Julius Watson, rf |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

John (Scotty) Alcock, 3b |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Owen Shannon, c |

3 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

(Big) Bill Chappelle, p |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

|

Totals |

31 |

2 |

5 |

27 |

21 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ATLANTA |

AB |

R |

H |

PO |

A |

E |

|

Dick Bayless, cf |

3 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

|

Roy Moran, lf |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Syd Smith, c |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Patrick (Patsy) Flaherty, rf |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Otto (Dutch) Jordan, 2b |

3 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pete Lister, 1b |

3 |

0 |

2 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

|

Scott Walker, 3b |

3 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

John Berkel, ss |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Hank (Pepper) Griffin, p |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

|

Totals |

26 |

1 |

5 |

27 |

14 |

0 |

|

Mobile |

000 |

001 |

001 |

2 |

|

Atlanta |

100 |

000 |

000 |

1 |

Summary: SO (by Griffin, 1); Walks (by Chappelle, 1); Wild Pitch (by Griffin, 1); Doubles (Bayless, Wagner); Triple (Seitz); Sacrifice Hit (Watson); Stolen Bases (Bayless, Flaherty, Lister, Murphy); Double Play (Berger-Seitz-Swacina); Triple Play (Watson- Swacina-Shannon). Umpire: Bill Hart. Game Time: 32 minutes.

*First names added by author

WYNN MONTGOMERY, author of the biography of Willard Nixon for SABR’s BioProject, has seen ballgames in every major-league city except Arlington, Texas, and in almost fifty minor-league parks. His article “Georgia’s 1948 Phenoms and the Bonus Rule” appears in the Summer 2010 issue of the Baseball Research Journal.

Sources

Baseball-Reference (www.baseball-reference.com) was my source for team records and the first names of most players.

Retrosheet (www.retrosheet.org) allowed me to review Greg Maddux’s game times and provided the information on modern-day game times.

Notes

1 Mike Zuckerman, Washington Times, 16 December 2009.

2 Jackson batted .354 for the Pelicans, almost 100 points higher than the team’s next best hitter, Frank Manush (.256), the older brother of Hall of Famer Heinie Manush.

3 Atlanta Constitution (25 September 1904). NOTE: The Atlanta Journal, 18 September 1910 lists the time of that 1904 game as 42 minutes.

4 Tom Akers, Atlanta Journal, 18 September 1910.

5 Nashville defeated New Orleans, 6-3. This game, which included 29 hits and 9 runs, may be even more remarkable than the Mobile-Atlanta contest.

6 Akers, Atlanta Journal, 18 September 1910.

7 These newspapers represent a sampling of the many found at NewspaperARCHIVE, available at www.newspaperarchive.com.

8 New York Times, 18 September 1910.

9 Akers, Atlanta Journal, 18 September 1910.

10 New York Times, 18 September 1910.

11 Atlanta Journal sports page headline, 18 September 1910.

12 He was also their leading pitcher with an 18–10 record and told the Atlanta Journal that he had once pitched a 40-minute game against a native Japanese team.

13 Akers, Atlanta Journal, 18 September 1910.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 As noted, this game was at least 10 minutes faster than the previous record. It also took 19 minutes less than the fastest major-league game, which (according to Answers.com) was played on September 28, 1919, in Philadelphia, with the Phillies losing to the New York Giants, 6–1.

17 This is a rough estimate, because the Atlanta Journal ’s box score (at left) contains a few obvious errors. It shows 33 official at bats for Mobile, but the individual numbers tally to only 31. From the narrative, we can deduce that Watson made the final out and should be credited with one more plate appearance, so the actual total seems to be 32. Watson’s sacrifice gives Mobile 33 plate appearances. Atlanta’s AB column totals correctly to 26, and the one walk to Flaherty raises the team’s plate appearances to 27, but we know that at least two more appearances occurred, because 27 Atlanta batters were retired, one scored, and one was left aboard in the first inning. Thus, we know that at least 62 plate appearances occurred during this 32 minute game—an average of just under 31 seconds. The teams also had to run on and off the field 17 times, which must have reduced actual playing time by at least a minute.

18 Akers, Atlanta Journal, 18 September 1910.