The 1877 National League’s Two Cincinnati Clubs: Were They In or Out, and Why the Confusion?

This article was written by Woody Eckard

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

In 1877 the National League began the season on April 30 with six clubs. However, in mid-June, the Cincinnatis disbanded for reasons only partly related to their poor on-field performance. A second Cincinnati club was quickly organized under different ownership and stronger financial backing. It began play less than three weeks after the first disbanded and was able to complete the first club’s league schedule.

Nevertheless, controversy swirled around the issue of whether either club qualified for league member ship. The league failed to clarify their status, even though its Constitution was quite clear in both cases. This suggests that the sustained ambiguity may not have been accidental. The matter was complicated by the fact that the success of the fledgling league was by no means assured, particularly given the ongoing economic depression of 1873-79.1

Then in December, both teams were disqualified and their games were excluded from the championship reckoning, i.e., they were not counted in the final standings. And for decades thereafter, published records generally were based on five members.2 Today, of course, Cincinnati is included in the 1877 National League standings as a single combined club with the records of the other five clubs adjusted accordingly.3 In 1968, the Special Baseball Records Committee restored both clubs to official status.4

This article reviews the history of this unique episode, focusing on the key question of why league officials allowed the ambiguity to persist. It has received little attention, perhaps because of its erasure by the Records Committee. It may also have been overshadowed by the Louisville game-throwing scandal that came to light at the end of the 1877 season.

THE TWO CLUBS

In 1876, the National League’s inaugural year, the Cincinnati Reds finished dead last in an eight-team circuit with a dismal 9-56 record. But in the first few months of 1877, local newspapers were waxing optimistic with reports of club management attempting to field a better team in the revamped six-club league. The Reds were owned and managed by Josiah L. Keck, with financial backing derived from the meat-packing firm of J.L. Keck & Brothers.

But then the well ran dry. A March 27 report in the Cincinnati Daily Star stated that “J.L. Keck & Bro. was announced to be in a critical condition yesterday,” perhaps a victim of the Depression.5 Two days later the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that “The Red Stocking Base-Ball Club now feel as if they have no backing, and talk of disbanding.”6 Then, on April 8, the Enquirer announced that “J.L. Keck & Brothers is no more,” its property having been sold to satisfy creditors.7

Nevertheless, on April 26 Josiah Keck attended the National League pre-season director’s meeting representing the Cincinnati Club.8 Apparently alternative financing had been secured. The Reds then began their season on schedule, winning their first game against the Louisvilles on May 10. But it was downhill from there. By June 16, their record was three wins and 14 losses, having lost seven straight since June 2.

This was enough for Keck, who decided to disband the club. Per the June 17 Enquirer. “Consultation with… the Club last evening confirms the belief that the proprietors…are ready to throw it [i.e., disband].”9 A June 19 Chicago Tribune article titled “The Cincinnatis Go to Pieces” reports: “Keck, the former head, … said he had no money to go on.”10 An Enquirer report, also on the 19th, stated that “members of the Cincinnati Club…were…released from their contracts.”11

Keck’s financial difficulties had another impact with broader implications. The club had failed to pay the $100 annual league membership dues that had a June 1 deadline. As seen here we quote from the relevant sections of the 1877 National League Constitution.12 Article VI clearly states that the penalty for non-payment is membership forfeiture. It also states that the League Secretary must notify all member clubs “at once.”

Relevant Sections of the 1877 National League Constitution13

Article III. Membership.

Section 4. …election [to membership] shall take place at the annual meeting…provided that should any eligible club desire to join the League after…the meeting and before the commencement of the ensuing championship season, it may make application in writing to the Secretary…[emphasis added].

Article VI. Dues and Assessments.

Section 1. Every club shall pay…on or before the first day of June…the sum of One Hundred Dollars…and any club failing [to comply] shall thereby forfeit its membership…and the Secretary of the League shall at once notify all League clubs of such forfeiture of membership [emphasis added].

However, for unspecified reasons, League President William Hulbert and Secretary-Treasurer Nicholas Young kept Cincinnati’s non-payment and its apparent non-member status secret until the disbandment, i.e., for more than two weeks. On June 25, a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article observed, “Young should have notified the League clubs at once; but Chicago was the only club that knew of it, none of the others having received a notification of [the payment] failure until the 19th.”14 Melville, in his 2001 book Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, suggests that Young’s inaction was actually at Hulbert’s request.15

Almost immediately after the first Cincinnati Club disbanded, a movement began to organize a replacement. The above-mentioned June 17 Enquirer article that reported the impending disbandment also mentioned that “a stock company of eight or ten of Cincinnati’s wealthiest men stand ready and anxious to take the Club off Mr. Keck’s hands.”16 Five days later, on June 23, a Cincinnati Star report indicated that a consortium was up and running.17 The new management had signed seven players from the old club, including five regulars; had closed a contract to rent the Reds’ ball park; and were communicating with league clubs regarding their position in the NL. The principals in the new organization were J.W. Neff and E.M. Johnson, both of Cincinnati. Nevertheless, Hulbert, ever the opportunist, “borrowed” star player Charley Jones for two games with his Chicago club in late June before the new Cincinnati club was a done deal, and also hired away two other players.18

A key issue was whether the new club could simply step in and finish the old club’s championship schedule. On June 19, the Cincinnati Enquirer observed “It would be self-robbery to any one of the League Clubs to deny its consent for the Cincinnati Club to remain in the League.”19 The reason, of course, is that denial could mean foregoing the related revenue. The five other 1877 members were the Bostons, Chicagos, Hartfords, Louisvilles, and the St. Louis Club. (The Hartfords played their “home” games in Brooklyn in 1877, the Mutuals having been booted from the league.)

But such approval need not involve formal admission to the league. After all, in the late 1870s league clubs played many games with non-league clubs as exhibitions, albeit with less fan interest. On June 22, the Chicago Tribune reported: “The [Cincinnati] Club will play out its schedule of games if taken back into the League. If not, it will play the schedule[d] games anyhow, with such of the League clubs as may wish it” (emphasis added).20 In the former case, the games would count in the championship standings, generating greater ticket sales; in the latter, they would not count, discouraging sales. Unfortunately, newspaper reports often conflated the two situations, confusing public understanding.

In fact, league rules forbade the admission of new clubs after the start of the championship season. Article III of the Constitution stipulates that the admission of new clubs must occur “before the commencement of the…championship season.” Thus, the new Cincinnatis could play out the old club’s schedule, but not as a member of the league.

The new club played its first NL opponent, Louisville, on July 3. After an early September team “reorganization” that involved replacing four starters, it completed its schedule on October 6 with a record of 12 wins and 28 losses, not much better than the old club. The combined record was 15 wins and 42 losses, ten games behind fifth-place Chicago. The November 10 Clipper presents a detailed season summary of game results for the “Old Team,” the “New Team,” and the “Reorganized Team.”21

AMBIGUOUS STATUS

Soon after the first club disbanded, a telegraph poll of the other clubs was conducted by the league, ostensibly to solicit approval for the new club as a replacement. On June 24, the Enquirer reported, “The Cincinnatis will be readmitted into the League—the five Clubs unanimously having voted to receive them.”22

It was clear from the poll that the new club would be allowed to play out the old club’s schedule. But, despite the wording in the Enquirer report, the championship-versus-exhibition status for the games was not made clear. For example, the July 9 Louisville Courier-Journal observed: “The League has not yet decided whether all the games of the Old Reds shall be thrown out or whether the new organization is to be admitted [to full membership] and its games counted. …no action has yet been taken upon the proposed admission of the new Reds…”23

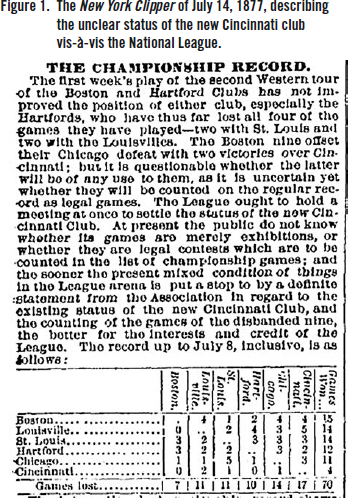

The Clipper of July 14 presented a more detailed critique of the Cincinnati Club’s ambiguous status (Figure 1), specifically calling for a “definite statement” of clarification from the league.24

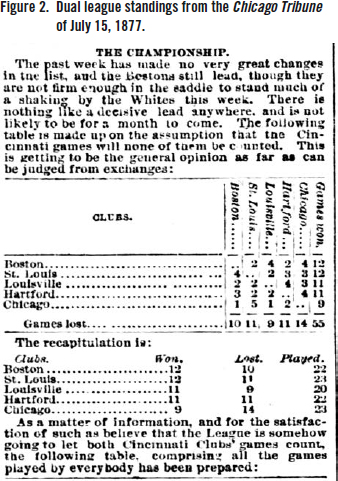

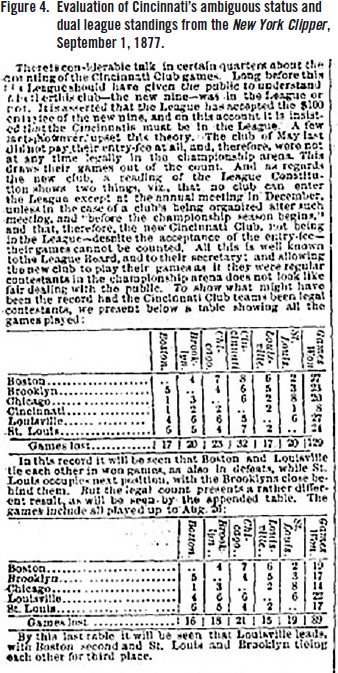

Newspapers reported NL standings in various ways after July 3. As noted by Pietrusza (1991), “So great was the confusion that some newspapers printed League standings featuring the rebuilt team, but others did not.”25 Many papers published separate standings, with and without Cincinnati. In the former case, the records of the two clubs were combined, assuming that, if admitted to the league, the new club would “inherit” the old club’s record. For example, Figures 2 and 3 show dual standings from the July 15 Chicago Tribune and August 6 Cincinnati Enquirer, respectively.26 The Clipper of September 1 was still reporting dual standings (Figure 4) noting: “Long be fore this the League should have given the public to understand [whether] this club—the new nine—was in the League or not.”27

THE NL’S CONUNDRUM

Certainly, the failure of the first Cincinnati Club presented a challenge. At the end of 1876 the NL had expelled the Mutuals of Brooklyn and Athletics of Philadelphia, representing its two largest cities. Both clubs had elected not to complete their schedule of games to avoid unprofitable end-of-season western road trips, a clear violation of the League Constitution. Now down to six members, the failure of the Cincinnatis not only made the NL’s viability look questionable, but possible associated revenue losses also could produce a serious financial threat, “jeopardizing the whole league,” as Pietrusza (1991) put it.28 Such concerns may have been exacerbated by the ongoing Depression. Additionally, the league had been widely criticized across the professional baseball community for its restrictive and exclusive business model, novel and as yet unproven.29

As Hulbert and Young no doubt knew of Keck’s financial problems, they may have decided to cut him some slack regarding the dues non-payment. By keeping it secret, the hope would have been that somehow he would find financial backing and keep operating. The fee would eventually be paid and counted as retroactive. But the disbandment dumped it all into the public domain. Hulbert and Young surely knew what actions the Constitution required…and allowed. Article XV stated that it could be “altered or amended,” but only at the annual League Directors’ meeting in December.

So, what to do? An announcement of strict application of the Constitution meant operating with only five clubs which, as noted above, could threaten the NL’s viability. One suspects that option was quickly rejected. But announcing ad hoc exceptions and counting the games of both clubs would create other problems. First, the league’s claim to be a rules-based organization, bound by its Constitution, would be seriously undermined, making future enforcement difficult. Second, Hulbert’s well-known prejudices against eastern cities would appear to be confirmed. The league’s many critics could then dismiss its rules-based claims as sheer hypocrisy, as enforcement occurred against the eastern Mutual and Athletic clubs while the midwestern Cincinnatis got a pass. Perhaps more seriously, the NL was now down to only two eastern cities (Boston and Hartford), and others might be deterred from joining, undermining the league’s aspirations to be the dominant national organization.

SUBTERFUGE

But a third course of action was available: say nothing about the status of the two clubs. Inaction works if the media and the baseball public-ticket-buying fans in particular—proceed under the assumption that the games might be counted, which is what happened. The league gets the revenue benefits of the new Cincinnati Club’s games, even if a status uncertainty penalty exists as some fans are deterred. Then, when the season ends, with the money safely banked, the Constitution is strictly applied, i.e., league member ship is denied to both clubs and their games excluded from the championship reckoning. This would be made easier by the fact that the new club was almost certainly a non-contender.

While attractive to the NL, this approach created risk for the Cincinnatis who would bear the brunt of reduced fan interest, especially given the economic vulnerability of a mid-season entrant. In fact, per the June 19 Chicago Tribune: “unless the League will admit the new [Cincinnati] association, they will not go on, they say.”30 Similarly, the Enquirer of the same date reported that the new ownership group “will not take the Club up unless they can regain a place in the League.”31 In other words, league membership was a condition of their participation.

Probably for this reason, the NL offered a major quid pro quo. The minutes of the league’s December 5, 1877, Directors’ Meeting describe “an agreement in writing, in…July, 1877 with [the new club]…to secure to the League the carrying out of the League schedule…of the [old club]” (emphasis added).32 In exchange, the “League clubs pledged themselves to vote for the admission of the [new club] to full membership” if the schedule was completed.33

Secrecy was necessary to create the uncertainty required for such a plan to be successful. Public knowledge would, in effect, constitute an announcement that the new club would not be granted league membership until after the season concluded. It would be equivalent to an initial announcement of strict constitutional enforcement, and that none of the new club’s games would count. Hulbert, Young, and the owners of the other teams apparently managed to keep their secret, as no reports of the plan in general or the July agreement in particular appeared in the press. Dual standings were widely reported until the season ended, evidence that secrecy had been maintained. And Hulbert, Young, and the other owners were apparently able to stonewall inquiries.

The NL’s clandestine plan, of course, yielded monetary benefits from the extra tickets sold to fans who were thinking the games were, or might be, championship games. The cost of unhappy fans apparently was seen as minimal compared to a five-club lineup, the resulting lost revenue, and a possible threat to league viability.

Sports writers howled, but demands for clarification simply could be ignored. While the reporters pointed out the league rules that denied membership to both clubs, it was also apparent that special exceptions could be made by the rule-makers themselves. And the regular reporting of two sets of standings implied that the latter outcome was not improbable, ironically aiding the league’s plan despite the newspaper writers’ general disapproval of the status uncertainty.

Seymour (1960) recognized the NL’s strategy vis-à-vis the 1877 Cincinnatis as “a clever [cunning?] practical solution which upheld League prestige by technically penalizing a violation without interrupting schedules or sacrificing gate receipts.”34 However, he did not mention the league’s duplicity or the critical roles played by public uncertainty and secrecy. Ellard’s 1908 book Baseball in Cincinnati: A History, in addressing the 1877 season, notes merely that “Cincinnati was officially dropped out of the National League…although a scrub team played the schedule through.”35 Similarly, Voigt (1983) mentions only that “for the immoral act of nonpayment of dues, Cincinnati’s 1877 record was disallowed.”36

While the contemporary newspapers did not explicitly identify the NL’s gambit, there were some inklings. For example, as early as July 9, the Daily Eagle observed that, with the current uncertainty, “if [Cincinnati’s games] are not [legal], the public is being led to attend under a species of false pretenses.”37 On July 21, the Clipper called out the “Boss of the League” [Hulbert], remarking that “the failure of the League to take action upon the Cincinnati Club’s position…is anything but in accordance with their profession of fair-dealing with the baseball public.”38 The September 1 Clipper article mentioned above reiterated this point, first noting the sections of the League Constitution that rendered the games of both Cincinnati clubs illegal. It then observed: “All this is well known to the League Board…and allowing the new club to play their games as if they were regular contests in the championship arena does not look like fair-dealing with the public.”39 These statements, perhaps originating with the influential Clipper Baseball and Cricket Editor Henry Chadwick, were thinly-veiled accusations.40

Be that as it may, the season concluded with Cincinnati’s status still unresolved. The league never issued a clarification. Their ploy succeeded.

RESOLUTION

Finally, the matter was resolved at the annual December meetings of the League Board of Directors. The Clipper reported that on December 4 the Board awarded the 1877 pennant to Boston based on the “regular League games played by the Boston, Louisville, Hartford [Brooklyn], St. Louis, and Chicago Clubs…All of the games played by…the Cincinnati Club were thrown out of the count.”41 Per the Constitution, the old club’s games were excluded for “not having paid the regular entry fee” and the new club was ineligible “having been organized after the opening of the championship season.”42 At the Board of Directors’ meeting the next day, the first public mention of the secret July agreement occurred (see above). Noting that the new Cincinnati Club had completed its schedule, per the agreement, the NL upheld its end by unanimously admitting the club for 1878.

But, alas, there was no mention of ticket refunds.

WOODY ECKARD, PhD is Professor of Economics Emeritus at the University of Colorado-Denver Business School. His academic publishing record includes several papers on sports economics. More recently he has published in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, The National Pastime, and Nineteenth Century Notes. He and his wife Jacky live in Evergreen, Colorado, with their two dogs Petey and Violet. He is a Rockies fan, both the baseball team and the mountains, and a SABR member for over 20 years.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions.

Notes

1. Per the official business cycle dating of the National Bureau of Economic Research, accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions.

2. For example, see Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1878 (Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bro., 1878), 57; and Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1939, ed. by John B. Foster (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1939), 63.

3. For example, see 1877 Cincinnati Red Schedule, Baseball-Reference.com, accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/CIN/1877-schedule-scores.shtml.

4. The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball (Toronto, Ontario: The Macmillan Company, 1969), 2328.

5. “Local Brevities,” Cincinnati Daily Star, March 27, 1877, 4.

6. “Who Will Do It Now?” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 29, 1877, 4.

7. “The firm of J.L. Keck & Brothers is no more,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 8, 1877, 6.

8. “Meeting of the National League Directors Yesterday,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 17, 1877, 2.

9. “Mr. Keck Refuses to Send the Cincinnatis on Their Eastern Trip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 17, 1877, 7.

10. “The Cincinnatis Go To Pieces,” Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1877, 5.

11. “The Cincinnati Red Stockings Step Down and Out,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 19, 1877, 2.

12. 1877 Constitution and Playing Rules of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bro., 1877), 5, 10. The original League Constitution of 1876 specified a January 1 due date. However, after the generally weak financial performance of league clubs in 1876, the date was extended by amendment to June 1 for 1877, allowing early season revenues to mitigate the associated burden on club coffers.

13. Source: 1877 Constitution and Playing Rules of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (Chicago, A.G. Spalding & Bro., 1877) 5, 10.

14. “The Cincinnati Club,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 25, 1877, 3. League president Hulbert also owned the Chicago Club.

15. Tom Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League (Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, 2001), 122.

16. “Mr. Keck Refuses to Send the Cincinnatis on Their Eastern Trip.”

17. “Base-ball,” Cincinnati Daily Star, June 23, 1877, 4.

18. “Cincinnati Made Happy,” Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1877, 7. After Hulbert was called out by several newspapers for his self-serving actions, and at Cincinnati’s written request, he penned a response in which he agreed to “willingly” (albeit not “gladly”) return Jones (only). See also David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball, 2nd ed. (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2006), 130-31.

19. “The Cincinnati Red Stockings Step Down and Out.”

20. “The Cincinnatis,” Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1877, 2.

21. “The Cincinnati Club Record,” New York Clipper, November 10, 1877, 261.

22. “Base-ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 24,1877, 6.

23. “Championship Summary,” Courier-Journal (Louisville), July 9, 1877, 1.

24. “The Championship Record,” New York Clipper, July 14, 1877, 123.

25. David Pietrusza, Major Leagues: The Formation, Sometimes Absorption, and Mostly Inevitable Demise of 18 Professional Baseball Organizations, 1871 to Present (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1991), 39.

26. “The Championship,” Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1877, 7; and “League Race,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 6, 1877, 8.

27. “The League Championship,” New York Clipper, September 1, 1877, 179.

28. Pietrusza.

29. Another few years would pass before the superiority of Hulbert’s model of a sports league organization and operation would be accepted.

30. “The Cincinnatis Go To Pieces.”

31. “The Cincinnati Red Stockings Step Down and Out.”

32. 1878 Constitution and Playing Rules of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bro., 1878), 46.

33. 1878 Constitution and Playing Rules of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs.

34. Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 89.

35. Harry Ellard, Base Ball in Cincinnati: A History (Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1908), 234.

36. David Quentin Voigt, American Baseball: From the Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System, Vol. 1 (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1983), 73.

37. “The League Pennant Contest,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 9, 1877, 3.

38. “The Championship Record,” New York Clipper, July 21, 1877, 131.

39. “The League Championship.”

40. Chadwick also wrote for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and may have been directly or indirectly responsible for the above-referenced articles from that paper.

41. “League Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 15, 1877, 298.

42. “League Association Convention.”