The 1906 World Series: The First World Series With Umpire Hand Signals

This article was written by R.A.R. Edwards

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

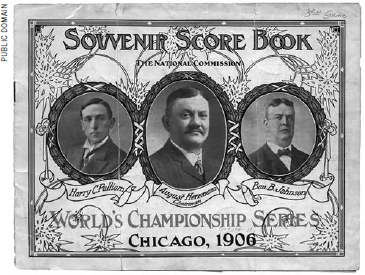

While the World Series returns to us annually, some Series live in legend forever. One of those classics was surely the 1906 World Series, which pitted the Chicago Cubs against the Chicago White Sox.1 The 1906 World Series was full of firsts. Being an all-Chicago affair, it was the first twentieth century “Subway Series”2 and marked the first twentieth- century appearance in the World Series for both teams.3 And while it would not be their last, their 1906 World Series appearance was the first for the Cubs’ famous infield of Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance.4 Sportswriter Franklin Pierce Adams would cement their legacy with these famous words, four years later: “These are the saddest of possible words: Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

But all of those firsts would be of little consequence if it were not a series that rewarded fans with unexpected drama, ending in a huge upset. The heavily favored Cubs, with the best record in baseball (116-36), were defeated by the White Sox, the so-called “Hitless Wonders,” who had the worst team batting average in the American League (.230) during the regular season. On their way to victory, the White Sox truly managed to outdo themselves in the Series, batting a mere .198 as a team.5

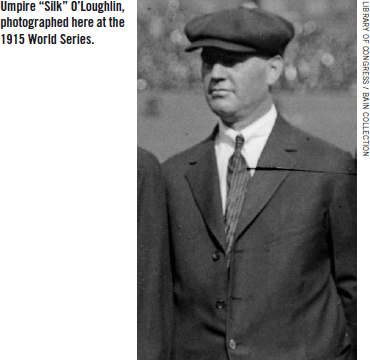

These are the important reasons that the 1906 World Series is memorable. Yet, arguably, its most lasting impact on baseball history lies elsewhere. This World Series was the first in which the umpires called the games with gestures behind home plate. In 1906, Jim Johnstone of the National League worked alongside American League umpire Francis “Silk” O’Loughlin. It was O’Loughlin’s first World Series appearance. Already recognized as “one of the greatest umpires that ever stepped on the field,” O’Loughlin made history in 1906.6

As the Chicago Tribune reported:

Fans who were fortunate enough to see the world’s series in this city last fall will recall that the din of rooting was so great it was impossible to hear an umpire’s decision. Umpire Johnstone, who worked behind the plate in the first game, had difficulty in making even the batteries understand his decisions. Next day, ‘Silk’ O’Loughlin supplemented his clarion voice with his characteristic gestures and his decisions were apparent to all. … (Before) the third game, both umpires were instructed to raise their right arms for strikes and their left arm for balls.7

There is a lot to unpack here. First, the impact of an intra-city Series leaps out. The noise was literally deafening. Second, what were these “characteristic gestures?” Third, how long had O’Loughlin been using them? Obviously, long enough that the Tribune thought of them as characteristic of the way that O’Loughlin called a game. Still, they were clearly not in use by most umpires. After all, it had not occurred to Jim Johnstone to use them, even as he struggled to make himself understood verbally. Fourth, where had these gestures come from?

The year 1906 holds all the answers. In April, just as the season was getting underway, the Washington Post reported that “O’Loughlin sprained his larynx Tuesday… and had no voice today. Instead of calling the decisions, he employed ‘Dummy’ Hoy’s mute signal code, which certainly was a novelty for Silk.”8 Over the course of the season, the use of Hoy’s signal code went from a “novelty” to a “characteristic” feature of O’Loughlin’s work.9

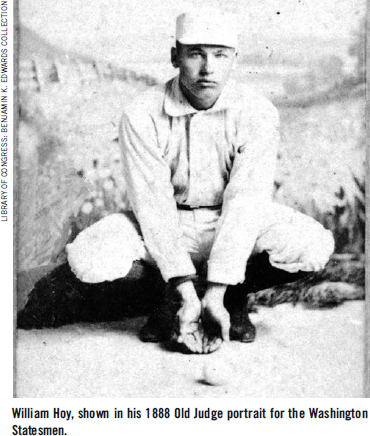

The reporters in 1906 acknowledged that the credit for the system should not go to O’Loughlin but to Hoy. The Post stated directly that O’Loughlin “employed ‘Dummy’ Hoy’s mute signal code.” Though not the first deaf player in major league baseball, Hoy was without question the most impactful. A center fielder, his career began with the Washington Nationals in 1888 and ended with the Cincinnati Reds in 1902.10

His system went with him from team to team. The Tribune described it in this way: “When Dummy Hoy was playing in the big leagues, his only method of ascertaining decisions on pitched balls was by watching the coach at third base, who held up his right hand when a strike was called on Hoy and his left hand for a ball.”11 The Tribune knew that fans had seen this system in baseball before and it was not original to hearing umpires.

Would O’Loughlin have seen Hoy’s system in use? In 1902, O’Loughlin was a rookie umpire. Hoy had just finished playing in Chicago, and was moving on to Cincinnati, taking his signal system with him. But it had left an indelible impression by this point, on both major leagues. The Washington Post reporter instantly recognized the thrust right hand for strikes and the upraised left for balls when O’Loughlin tried it out in April 1906 as “Dummy Hoy’s mute signal code.”

Hoy stated back in 1900 that his system was “well understood by all the League players.” He added that fans liked the system too, as “I have often been told by frequenters of the game that they take considerable delight in watching the coacher signal balls and strikes to me, as by these signals they can know to a certainty what the umpire with a not too overstrong voice is saying.” He further explained that the “reason the right hand was originally selected by me to denote a strike and the left hand to denote a ball was because ‘the pitcher was all right’ when he got the ball over the plate and because ‘he got left’ when he sent the ball wide of the plate.”12

The Chicago Tribune was confident that Hoy’s signs were coming to baseball permanently. “The movement for a system of signals to indicate an umpire’s decisions during a baseball game…seems to be spreading,” the paper declared in January 1907, predicting that baseball “will adopt some such system before another playing season arrives.”13Sporting Life had reached a similar conclusion by February 1907, noting, “The umpire arm- signal plan, so well demonstrated during the world’s championship series, is growing in favor, and, from appearances, will be in general use next season.”14

But just as Sporting Life thought the matter settled, the Tribune broke a story in February 1907 revealing that “electrical score boards operated from near the home plates probably will be adopted by the American league clubs to indicate to spectators every decision made during a game instead of the signal system by umpires’ gestures, which has been under consideration.”15Sporting Life picked up the same report, with additional sourcing, explaining that “the scoreboard idea results from the protest of Hank O’Day and other knights of the indicator on the making of themselves human windmills trying to interpret balls and strikes to the fans in the bleachers.”16 The scoreboard would replace the gesture idea. Such boards were considered “simple,” “practical,” and “reliable.”17

Unconvinced, the Tribune pointed out the obvious weakness to the scheme; namely, the scoreboard operator still needed to know what the call was in order to post it. Without implementing a gesture system for the umpires, the scoreboard operator would have to guess at the call. Besides, the paper went on, “the real fan does not like to take his eyes off the play long enough even to glance at a scoreboard except between innings….From the patron’s standpoint, therefore, no scoreboard can replace an umpire’s gestures.”18 In this way, the Tribune essentially argued that all baseball fans are deaf; they all rely on vision, not hearing, to understand the game unfolding on the field before them.19

Things came to a head in 1907. Umpires formally came out “against the proposed rule to have umpires wave their arms to designate balls and strikes.”20 But, at the turn of the century, their resistance was hardly surprising. Given that the system of gesturing originated with a deaf ballplayer, it would have been directly associated with deafness and with sign language, both of which were increasingly stigmatized as abnormal at the turn of the century.21

American Sign Language was under attack, as educators sought to eliminate it from schools. By 1907, teachers argued that “our first and foremost aim has been the development of the deaf child into as nearly a normal individual as possible.”22 Only by speaking, and never signing, could a deaf child become normal. A new ideal was emerging for deaf people, the ideal of “passing” as a hearing person.23 Deaf students who failed to do so were mocked; as historian Susan Burch notes, they “found themselves labeled as ‘oral failures’ and ridiculed as ‘born idiots.’”24

Deaf people were under attack in other ways. In 1907, the federal government updated the Immigration of Act of 1882 to bar entry to persons with “a physical defect being of a nature which may affect the ability of such an alien to earn a living.” Deaf immigrants found themselves turned away at Ellis Island, as hearing immigration officials assumed that deafness would render them unemployable.25

The American deaf community had few defenders of either its members or its language in the early twentieth century. But they had William Hoy. Hoy became a prominent symbol of deaf success in a hearing world. He signed, and did not speak, and he valued his deafness, arguing that it offered him an advantage over hearing players. In 1902, Hoy explained how being deaf positively affected all parts of his game:

In batting there is really little handicap for a mute. I can see the ball as well as others. … I think, perhaps, the fact that I have to depend so much on my eyes helps me in judging what the umpire will call a strike, and if the ball delivered is a little off I wait for four bad ones. In base running the signals of the hit and run game and other strategies are mostly silent, the same as for the other players. By a further system of signs my teammates keep me posted on how many are out and what is going on about me. … Because I can not hear the coaching I have acquired the habit of running with my neck twisted to watch the progress of the ball. I think most players depend too much on the coachers and often a man is coached along too far or not far enough, when, if he knew where the ball was himself, he would know what chances were best for him to take. In judging fly balls I depend on sight alone and must keep my eye constantly on the batsman to watch for a possible fly, since I can not hear the crack of the bat. This alertness, I think, helps me in other departments of the game. So it may be seen, the handicaps of a deaf ball player are minimized.26

Hoy challenged the expectations of hearing Americans; they saw hearing loss but Hoy saw deaf gain.27

At least in baseball, hearing reporters and fans came to recognize the benefits and contributions of deaf people. The deaf way to communicate, by gestures, was seen as superior to the hearing solution of screaming louder. In the face of the umpires’ resistance, the Tribune changed tactics. It moved to attack them, complaining that there was “too much consideration for the umpires.”28Sporting Life did likewise, arguing, “The umpire who cannot use the arm signal system without confusion or trouble is not fit even for amateur umpiring. … The system was tried in the world’s championship series and worked to a charm …”29 The press hoped that umpires would voluntarily agree to experiment with it.

It seems that this is what happened. Though umpires, as an organized body, resisted the system, some of their number reluctantly tried their hand at it. Bill Deane notes that “umpires’ hand signals were in mass usage by 1907, though standardization was lacking.”30 Unsurprisingly, O’Loughlin kept using gestures. Sporting Life noted his work, writing, “Silk O’Loughlin … is also in a class by himself. Silk yells ‘Stri-i-ik’ with particular emphasis on the ‘I’ and draws his right hand back over his shoulder and points his thumb at the grandstand. When he calls a ball, he makes no movement with his hands. Silk calls two ‘TUH,’ which never fails to raise a laugh.”31

The signs of baseball did not have much longer to wait. In 1909, they were made mandatory in both leagues. A majority of umpires had apparently concluded that such a system would not be too difficult to use. Perhaps O’Loughlin’s continued use of the system had helped to change minds. Or, perhaps, umpires had finally been persuaded that baseball was indeed a business. Catering to the needs of paying customers was a priority for baseball owners. As the Sporting Life acidly commented in 1907, “It is a reflection on the intelligence of umpires that they should require command to uniformly employ so simple a method of pleasing the patrons of the sport.”32

Fans at the World Series in Chicago in 1906 could scarcely have imagined what the future would hold. How could it be that Chicago would not see another Subway Series in the remainder of the century? How could the Cubs go from three consecutive World Series appearances, which yielded two championships, to a century-and-change long World Series drought? At least, Tinker to Evers to Chance would live forever.

Sadly, the contributions of Hoy and O’Loughlin would not. There remains resistance in baseball to the historical fact that Hoy brought the signs to baseball. A 2012 book flatly called it “a myth.”33 In truth, “Dummy Hoy’s mute signal code” entered baseball, was popularized during the 1906 World Series, and those signals are with us still.34 But the man himself has not been given the recognition that he deserves. Neither has O’Loughlin. He died in 1918, a victim of the flu pandemic. With his career cut short, his pathbreaking part in bringing Hoy’s signs to baseball was soon forgotten. Today, if you visit the National Baseball Hall of Fame, neither Hoy nor O’Loughlin have plaques. Instead, visitors learn that the man who brought the signs to baseball was umpire Bill Klem. As his plaque reads, in part, “Umpire. National League 1905-1951. Umpired in 18 World Series. Credited with introducing arm signals indicating strikes and fair or foul balls.”

This plaque provides an unexpected twist to the story, namely, a surprise ending. In 1906, O’Loughlin could hardly have imagined that the credit for his achievement would someday be given to a man whom he helped to break into major league baseball. O’Loughlin helped to arrange the professional introductions for Bill Klem that allowed him to advance out of the minor leagues and into the National League in 1905.35 Klem’s first World Series appearance came in Chicago, too— but in 1908, when the Cubs faced the Tigers, two years after O’Loughlin brought Hoy’s signs to the World Series, where they have been ever since.

R.A.R. EDWARDS is a professor of history at the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, New York. A native of Connecticut, she is a life-long Red Sox fan. Her most recent book was “Deaf Players in Major League Baseball: A History, 1883 to the Present” (McFarland, 2020). It was recognized with a SABR Baseball Research Award in 2021.

Notes

1. For more on this Series, see Bernard A. Weisberger, When Chicago Ruled Baseball: the Cubs-White Sox World Series of 1906 (New York: Harper, 2006).

2. While the term “Subway Series” for an intra-city World Series was not widely popularized until after the World Series became a regular all-New York City affair, it may be applied in spirit to the city of Chicago, despite Chicago not having a subway until 1943.

3. The Cubs had been in the 1885 and 1886 “World’s Series.”

4. For more on the trio, see David Rapp, Tinker to Evers to Chance: The Chicago Cubs and the Dawn of Modern America (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018).

5. This might seem like the performance floor, but in a list of the thirteen worst team batting averages in the history of the World Series, my Boston Red Sox managed to come in both first (1918 appearance, with an average of .186) and last (2013 appearance, with an average of .211). Talk about winning the hard way. And no, a decade later, I am still not entirely sure that the 2013 win makes up for the 2011 collapse, thanks for asking. And thanks, ESPN, for providing an online list to torture ourselves with.

6. Timeline of his career in “Silk O’Loughlin King of Umps,” Sunday Vindicator, April 29, 1906, 13.

7. “Gestures to Tell Umpire’s Ruling,” Chicago Tribune, January 6, 1907, A1.

8. “Nationals Lose Game,” Washington Post, Thursday, April 19, 1906, 8.

9. “Silk O’Loughlin Unique Umpire,” Meriden Daily Journal, October 16, 1906, 11.

10. For more on Hoy’s career see R.A.R. Edwards, Deaf Players in Major League Baseball: A History, 1883 to the Present (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2020).

11. “Gestures to Tell Umpire’s Ruling,” Chicago Tribune, January 6, 1907, A1.

12. “Calling Balls and Strikes,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1900, 5.

13. “The Referee: Sporting Comment of the Week,” Chicago Tribune, January 20, 190, A1.

14. “Easy To Execute,” Sporting Life, February 23, 1907, 4.

15. “Electrical Score Boards for the American League,” Chicago Tribune, February 13, 1907, 12

16. “Johnson’s Idea,” Sporting Life, February 23, 1907, 10. O’Day remains the only man to play, manage, and umpire in the history of the National League. He served as an umpire in the World Series in 1903, and would serve in 10 World Series over the course of his career. When O’Day died in Chicago on July 2, 1935, former NL president John Heydler called him one of the greatest umpires ever in terms of knowledge of the rules, fairness, and courage to make the right call. Umpire Bill Klem, however, referred to him as a “misanthropic Irishman,” while Christy Mathewson said that arguing with O’Day was like “using a lit match to see how much gasoline was in a fuel tank” (David Anderson, “Hank O’Day,” SABR Baseball Biography Project).

17. “Electrical Score Boards for the American League,” Chicago Tribune, February 13, 1907, 12. The Yankees are usually credited for first using an electronic scoreboard in baseball, in the original Yankee Stadium, when it opened in 1923. See G. Edwards White, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself 1903-1953 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 41-42. These 1907 articles, however, repeatedly point to this forerunner apparently in use in St. Louis as the inspiration for Johnson’s plan to adopt them throughout the American League. For more on the history of electronic scoreboards in baseball, see Rob Edelman, “Electric Scoreboards, Bulletin Boards, and Mimic Diamonds,” Base Ball 3, 2, Fall 2009, 76-87.

18. “The Referee: Sports Comment of the Week: Signaling Balls and Strikes,” Chicago Tribune, February 17, 1907, A1.

19. In theorizing fans as deaf, I follow the lead of Lennard Davis, who argues that the rise of reading in the eighteenth century similarly transformed hearing people. “Even if you are not Deaf,” he writes, “you are deaf while you are reading. You are in a deafened modality or moment. All readers are deaf because they are defined by a process that does not require hearing or speaking (vocalizing).” See Davis, Enforcing Normalcy: Disability Deafness, and the Body (New York: Verso, 1995), 4, 50-72.

20. “Echoes of the Diamond,” Washington Post, March 1, 1907, 8.

21. See Douglas C. Baynton, Forbidden Signs: American Culture and the Campaign Against Sign Language (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

22. Oralist teacher as quoted in Baynton, Forbidden Signs, 146.

23. For more on passing, see Baynton, Forbidden Signs, 146-48. See also Susan Burch, Signs of Resistance: American Deaf Cultural History, 1900 to 1942 (New York: New York University Press, 2002), especially 146-49, and R.A.R. Edwards, Words Made Flesh: Nineteenth-Century Deaf Education and Growth of Deaf Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2012), especially 158-9, 200.

25. See Douglas Baynton, “‘The Undesirability of Admitting Deaf Mutes’: U.S. Immigration Policy and Deaf Immigrants, 1882-1924,” Sign Language Studies 6, 4, Summer 2006, 391-415. See also Douglas C. Baynton, Defectives in the Land: Disability and Immigration in the Age of Eugenics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

26. Dummy Hoy as quoted in “How A Mute Plays Ball,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 5, 1902, 22.

27. For more on ‘deaf gain,’ see H-Dirksen L. Bauman and Joseph J. Murray, eds., Deaf Gain Raising the Stakes for Human Diversity (University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

28. “The Referee: Sporting Comment of the Week: Too Much Consideration for the Umpire,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1907, A1.

29. “Easy to Execute,” Sporting Life, February 23, 1907, 4.

30. Bill Deane, Baseball Myths: Debating, Debunking, and Disproving Tales from the Diamond (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2012), 20.

31. Sporting Life, October 19, 1907, 8.

32. “Timely Topics,” Sporting Life, May 18, 1907, 7.

33. Bill Deane, Baseball Myths: Debating, Debunking, and Disproving Tales from the Diamond (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2012), 17, 21.

34. In Peter Morris’s book, A Game of Inches (2010, Ivan R. Dee Publishers), he attributes the earliest use of the umpire hand signals to Ed Dundon in 1886. Dundon had been a teammate of Hoy’s at the Ohio School for the Deaf. See Brian McKenna, “Ed Dundon,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ed-dundon.

35. Klem discussed his professional relationship with O’Loughlin in William J. Klem and William J. Slocum, “I Never Missed One in my Heart,” Collier’s, March 31, 1951, 59. See also David Anderson, “Bill Klem,” entry in The Baseball Biography Project, SABR.org.