The 1945 Pennant Races

This article was written by Douglas Jordan

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

From a historical perspective, the primary event that took place in 1945 was the conclusion of World War II. But the war was still raging at the end of 1944, and additional manpower was needed to ensure victory over the Axis powers. Because of this, in December 1944, the director of War Mobilization and Reconversion, James Byrnes, ordered all dog and horse racing tracks to be closed in January 1945.1 He argued that people working in the industry would be better employed in the war effort, and that the fuel used by the industry, and by patrons getting to the races, was needed by the armed forces.

The order made the status of the upcoming baseball season uncertain as the calendar turned to 1945. Would the same edict be applied to other sports, including baseball? On New Year’s Day, Byrnes assured reporters that other sports would not be shuttered, but that the policy for 4-F draft deferments for athletes would be tightened.2 That could be a big problem for major league baseball: At one point in 1944, 260 out of 400 players (65 percent) were designated 4-F.3 How would teams replace players if more of them were draft eligible in 1945?

Uncertainty associated with the answer to this question persisted through Opening Day. A directive was issued on January 20 that required War Department review of all 4-F professional athletes.4 Some players were still considered 4-F after these reviews but many were not. There was also uncertainty about 4-F players working in war related industries. Their status wasn’t clarified until March 21, when the War Manpower Commission issued a directive allowing professional baseball players to leave their jobs until October to play.5

With many major league players already serving, the end result was that the rosters of major league teams when the season opened on April 17 consisted of a mixture of men too young or too old to serve, plus some 4-F players. A detailed discussion of the composition of major league rosters during World War II is beyond the scope of this article. However, there is a general perception that the overall quality of play was inferior to non-war years, especially in 1945. During that year, H.G. Salsinger of the Detroit News wrote, “Even the most charitable and amiable of men must admit that the quality of major league baseball in the current season is the poorest in more than 50 years.”6

The perception of low-quality play is not shared by all. SABR member Renwick Speer argued against the notion in a 1983 Baseball Research Journal article.7 He noted that major league players such as Lou Boudreau, Frank Crosetti, Babe Dahlgren, Phil Cavarretta, Al Lopez, Marty Marion, and Mel Ott did not miss a full season during the war years. Speer concludes, “We maintain that a good brand of baseball was played in the major leagues during World War II without pretending to imply that it was the same without Pee Wee, the Yankee Clipper, Rapid Robert, and the Kid.”

Regardless of the quality of play, what cannot be disputed is that there were two exciting pennant races in 1945. After play on Sunday, September 23, the two American League contenders were separated by a single game. The leaders in the National League were 1½ games apart. The World Series contestants were decided over the last week of the season. The purpose of this article is to examine and discuss the 1945 season to see what led to its exciting conclusion.

METHODOLOGY

Pennant races are usually described verbally based on the number of games separating teams. Fans are very comfortable with this convention, but there are two drawbacks associated with it. First, the standings in terms of games behind on any given day do not show what has happened over time. In addition, games behind is a relative measure because it is based on how far each trailing team is behind the leading team. The relative positions can change because the trailing teams are playing well, or because the leading team is playing poorly, but fans can’t know from looking at the standings on a particular day how the teams have fared recently.

Both of these drawbacks can be alleviated by using a graph of the standings over time. Unfortunately, a graph of games behind over time does not solve the relative position issue. That problem can be fixed by graphing the number of games over .500 for teams instead of games behind. A level line from data point to data point means the team played exactly .500 ball over the time period. A line with a positive or negative slope means the team played better or worse than .500 ball. Therefore, the discussion of the 1945 pennant race in this paper will be based on graphs of games over .500 for the teams under consideration. The more familiar number of games behind is always just half the difference in games over .500. Unless otherwise noted, all data are taken from Baseball-Reference.com.

SETTING THE STAGE

No baseball season exists in a vacuum. Teams and players that fared well the previous year are usually expected to do well again during the current season. Therefore, a brief discussion of the 1944 season and a few broader items will set the stage for the 1945 campaign.

With the exception of New York City, it is rare for two teams from the same city to play in the World Series. The only time that happened in St. Louis was in 1944. In the American League, the St. Louis Browns went 14–3 over their last 17 games that year. The Detroit Tigers went 13–4 over the same period. The two teams were tied with one game left in the season. The Browns won and the Tigers lost on the final day of the campaign to give the Browns the only pennant they won in over 50 years in St. Louis (the franchise moved to Baltimore in 1954). The Washington Nationals came in last with a 64–90 record.

There wasn’t a pennant race in the National League in 1944. The St. Louis Cardinals dominated the league with 105 wins. The Pittsburgh Pirates’ 90 victories were second best. It was the third consecutive year the Cardinals had won the NL pennant and won more than 100 games. The only other team with three straight 100-win seasons before the Cardinals was the Philadelphia Athletics from 1929–31.8 The Cardinals won the World Series four games to two. One notable aspect of the Series was that every game was played in the same ballpark, since the two teams shared Sportsman’s Park as their home field.9

The Cardinals’ chances for a fourth consecutive pennant were reduced when three 1944 All-Stars had to serve in the military in 1945. Stan Musial missed the entire season, and catcher Walker Cooper and hurler Max Lanier played briefly before being called up. The pitching staff took another blow when 22-game winner Mort Cooper, who had feuded with St. Louis owner Sam Breadon over his salary, was traded to the Boston Braves early in the season for nine-game-winner Red Barrett.

The two pitchers switched roles in 1945. Barrett collected 21 wins for the Cardinals while an elbow injury limited Cooper to 11 starts for the Braves.10 In addition to the surprise performance from Barrett, the Cardinals got an unexpected contribution from rookie pitcher Ken Burkhart, whose 18 wins and 2.90 ERA helped keep the Cardinals in contention through the year. In light of what happened in 1945, it should be noted that the Chicago Cubs finished the 1944 season 30 games out of first place with a 75–79 record.

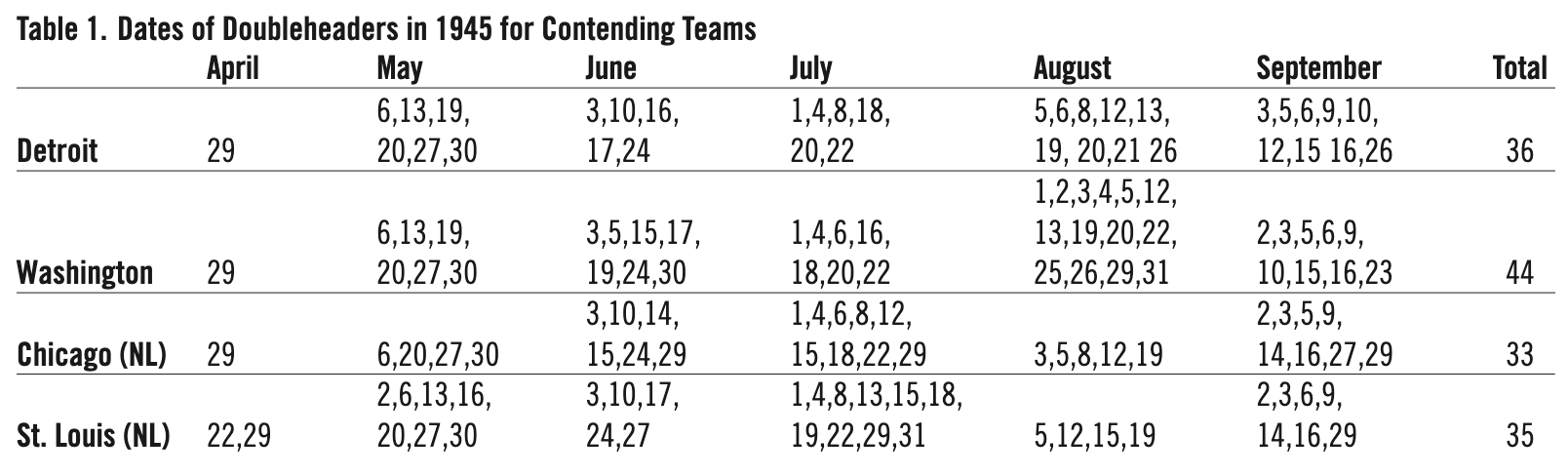

The 1945 baseball schedule contained an unusually high number of doubleheaders. This was done in order to minimize team travel in response to wartime travel restrictions.11 Table 1 shows the dates of 1945 doubleheaders for the top two teams in each league. The schedule was a success in in minimizing travel, but it made the season a relentless grind for the players. This was justified as a wartime necessity, but it exhausted the players, especially pitchers, and made the last two months of the season as much a test of survival as a race for the pennant.12

The American League contenders got the worst of it. Detroit played six doubleheaders in May and July. This was followed by nine in both August and September for a total of 36 doubleheaders over the course of the season. The Nationals had it even worse. The team played seven doubleheaders in both June and July, and then had an incredible 14 twin bills in August, with nine more in September. The Nationals played a doubleheader on five consecutive days at the beginning of August (going 9–1 over those 10 games), and a total of 44 over the course of the campaign.

Why did the team play so many games the last two months of the season? In addition to wartime travel restrictions, the Nationals owner, Clark Griffith, had agreed to let the Washington professional football team use the field during the last week of the baseball season, so the Nats had to finish their schedule on September 23 instead of September 30. It’s likely that Washington was able to stay competitive in spite of having to play so many games during the last eight weeks because the pitching staff had four knuckleball pitchers. Dutch Leonard (17–7), Roger Wolff (20–10), Mickey Haefner (16–14), and Johnny Niggeling (7–12) all featured the easier-on-the-arm knuckleball.

Griffith’s early adoption of night baseball (the Nationals played more night games than any other team), which allowed wartime workers to go to games and increased attendance, also helped the knucklers. “The knuckler has the edge under the lights,” Wolff said. “Leonard and Niggeling and myself ought to do all right.”13 Wolff was right. Data from the 1945 season show the four pitchers had a combined 2.84 ERA during the day vs. 2.20 at night. The day/night split for batting average against was .243/.218. But these better pitching numbers didn’t translate into more wins. The Nationals had a .550 winning average at night against a .570 winning average during the day.14

The overall quality of play may have had something to do with the quartet’s success. Collectively weaker hitting in 1945 may have enabled Washington to rely on a primarily knuckleball-pitching staff. The history of night baseball is tangential to this story. However, a short digression will be of interest given the modern tendency to play games at night. The first night game was played in Cincinnati in 1935. But baseball was very slow to adopt the innovation. Why was that? The short answer is because of the attitude of the owners. “Why, this night game is baseball’s ruination. It changes baseball players from athletes to actors. It’s nothing more than a spectacle,” said Tigers owner Frank Navin.

Sportswriter H.G. Salsinger, summarizing the attitude of the time, wrote, “Baseball was made to be played in the daylight. It just isn’t as good at night, it can’t be. Infielders can’t get a jump on the ball at night. Ground balls go through the infield that would be fielded in daylight. You cannot see the spin of the ball at night—only a white object sailing at you. Night baseball is a much inferior game.”15

THE FIRST FOUR MONTHS OF THE 1945 SEASON

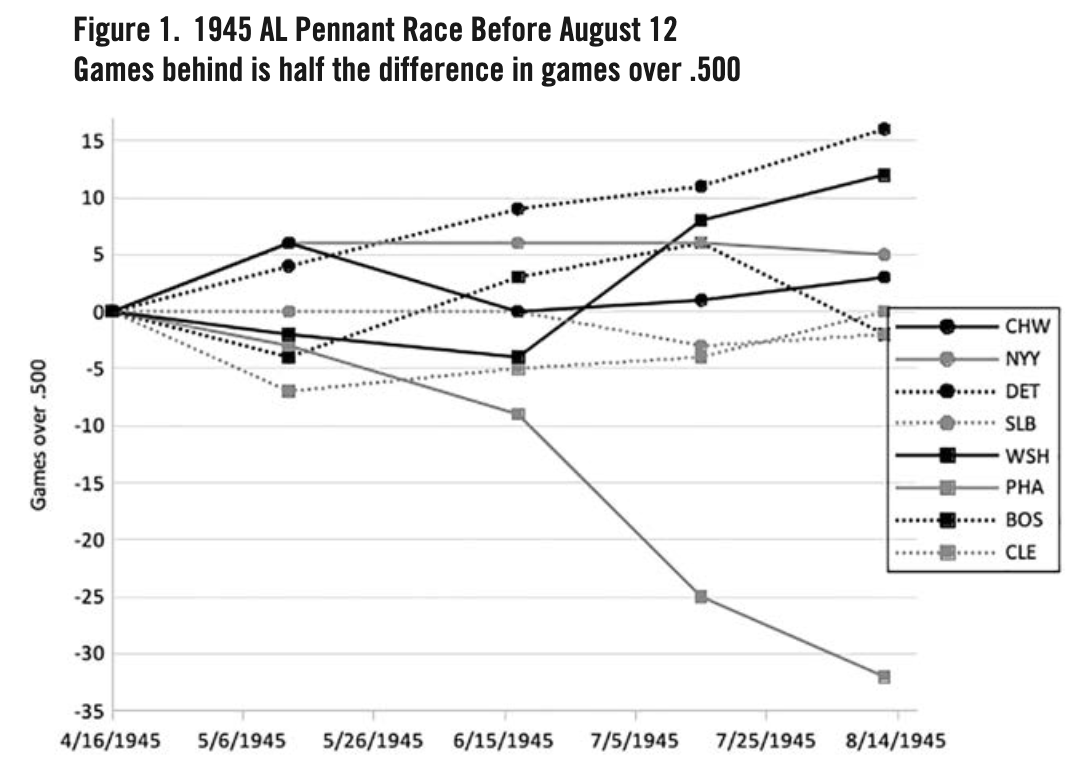

The performance in terms of games over .500 for the American League over the first two-thirds of the 1945 season is shown in Figure 1.

Figures 1 and 2 are a little confusing because they show the performance of all eight teams in each league. The easiest way to understand each graph is to start with the team names on the right side and follow the line for a particular team from right to left in order to see what happened to the team earlier in the season.

In Figure 1, the data points for Boston and St. Louis are on top of each other. Therefore, there are two lines coming out of the sixth data point and there are seven (instead of eight) final data points on the far right side. In 1945, the season opened on Tuesday, April 17. The AL standings after play on Sundays at approximately monthly intervals are displayed in Figure 1. One month into the season the New York Yankees and Chicago White Sox led the league with the Tigers just a game behind, and the defending champ Browns three games in arrears with a .500 record. However, the standings that day were of minor importance compared with the news that Germany had surrendered on May 8.

In addition to the national jubilation that followed V-E Day, the implications for baseball were significant. Two million soldiers, including many major league players, were to be released within the next year, and War Department reviews of 4-F professional athletes were suspended.16 This resulted in many players returning to their teams over the course of the 1945 season.

By mid-June, the Tigers had moved into first place and the White Sox had fallen off the pace. The Yankees trailed Detroit by 1 1/2 games while the Nationals were four games under .500 and 61⁄2 games behind. Two of the most important events of the season (from an AL pennant race perspective) occurred between mid-June and mid-July. The Nationals went 18–6 over the month to move into second place, just 1 1/2 games behind Detroit, on July 15. The most surprising aspect of this run was that most of it took place on a 19-game road trip.

Both teams got some excellent news in this timeframe. Hank Greenberg, one of the first major league players to go into the service, returned to the Tigers on July 1. He hit the 250th home run of his career in his first game back. The Nationals got an offensive boost from the return of Buddy Lewis on July 27. Although Lewis did not have Greenberg’s power, he batted .333 with 37 RBIs over 69 games to provide an offensive boost to a Nationals team that batted .258 on the season. These two teams continued to play well over the next month. They had separated themselves from the rest of the league by August 12, with the Tigers leading the Nats by two games.

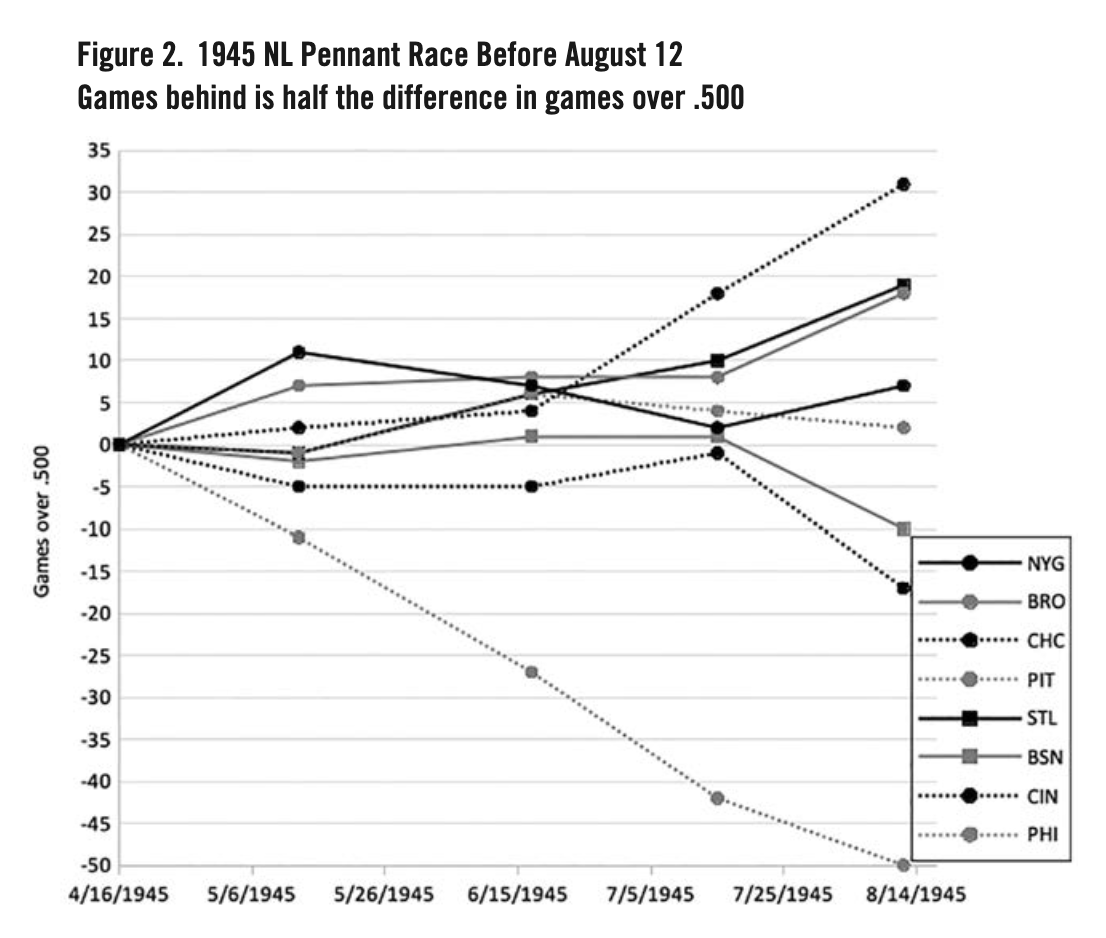

The race in the National League prior to August 12 is shown in Figure 2. The two NL teams in New York got off to fast starts in 1945. The New York Giants went 16–5 over the first month to lead the Brooklyn Dodgers by two games just after V-E Day. Both teams fell back to the rest of the NL pack over the following month, so by mid-June, the top six teams in the NL were separated by just 3 1/2 games, with Brooklyn on top.

As in the AL, the next month was significant for the pennant race. The Cubs went 21–7 (which included a 13–3 road trip) to take a four-game lead over the Cardinals by mid-July. The Dodgers were just a game behind St. Louis. Chicago continued to play well for the next month, going 21–8 from July 16 to August 12. This increased their lead over St. Louis to six games with Brooklyn trailing the Cardinals by just a half game at the end of play on August 12.

THE FINAL SEVEN WEEKS IN THE AMERICAN LEAGUE

Although the war in Europe had ended in May, the conflict with Japan continued as the calendar turned to August. Thousands of men were sent to the Pacific Theater in preparation for an invasion of the Japanese mainland. Casualties on both sides were expected to be very high during the invasion. But a new weapon of war and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war against Japan on August 8 changed the course of history. Japan surrendered on August 14 after atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9.

From a baseball perspective, the end of the war meant that all of the former players would be coming back. The only question was whether they would return in time for them to play in 1945. Two prominent examples were Bob Feller and Joe DiMaggio. Feller’s highly anticipated return occurred on August 24 against the Tigers in Cleveland. It seemed as though he’d never been away. The Indians beat the Tigers 4–2 behind Feller’s complete game four-hitter (with 12 strikeouts). But the War Department didn’t discharge DiMaggio in time. His return would have to wait until 1946.

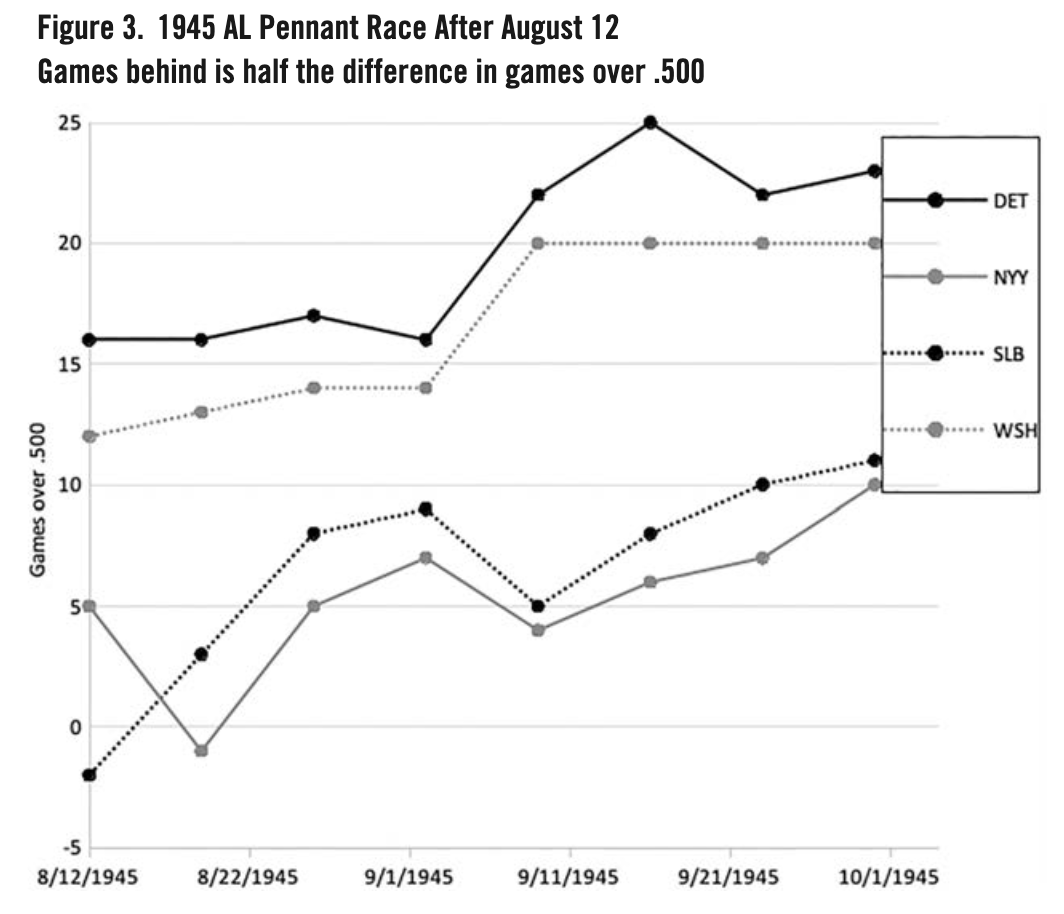

The last seven weeks of the pennant race in the AL are shown in Figure 3. There are several differences between the first roughly two-thirds of the race in Figure 1 and the last third in Figure 3. First, in order to focus on the contest for the pennant, only the top four teams in the league are shown. In addition, the results are shown weekly, rather than monthly.

Figure 3 shows that the league-leading Tigers stayed 16 games over .500 between August 12 and September 2, while the Nationals moved from 12 to 14 games over .500. This left Washington one game behind after play on the second day of September. The Nationals made up some of that ground by winning three out of four during a series in Detroit August 15–18. Although it is not shown in Figure 3, Washington trailed by just a half game on August 22 and August 24.

In spite of the heavy workload, Washington went 9–3 in the 12 games after September 2. But unfortunately for the Nationals, Detroit (which played five doubleheaders in the same timeframe) also played very well that week, so the Tigers maintained a one game lead after play on Monday, September 10. Detroit’s lead was reduced to a half game as the Tigers entered a crucial five-game series (back-to-back doubleheaders on Saturday and Sunday, with another game on Tuesday) against the Nationals in Washington starting on Saturday, September 15.

The Nationals’ chances to move into first place were improved because Greenberg could not play due to injury.17 Pitching, which had been the strength of the Washington club all season, did not perform well during the Saturday twin bill. The Nationals allowed seven runs in both games and were swept, leaving them 2 1/2 games back. A split on Sunday and a victory on Tuesday left them 1 1/2 games behind with just five more away games on their truncated schedule. Washington still trailed by 1 1/2 games entering its final two games, against the A’s in Philadelphia on September 23. The Tigers lost to the Browns that day, so a sweep by the Nationals would have put them into a virtual tie for first place. The Nationals won the nightcap, but the first game has gone down in infamy for Washington fans. Leading 3–0 in the middle of the eighth inning, two consecutive Nationals errors put men on first and second with no outs. That led to three unearned runs for the Athletics, and the game went into extra innings.

In the top of the 12th inning, the A’s center fielder, Sam Chapman, was having trouble with the sun so he requested timeout to have his sunglasses brought out. Bingo Binks, the Nationals center fielder, didn’t take the hint. He went out for the bottom of the 12th without sunglasses. With two outs, Binks lost an easy popup in the sun, and the batter, outfielder Ernie Kish, reached second base. Kish scored on a single by George Kell to give Philadelphia a walk-off victory, leaving Washington one game behind the Tigers as their season ended.18

Detroit had four games scheduled for the following week. If the Tigers lost three of four they would be tied with the Nationals. They split the first two games before traveling to St. Louis for a season-ending doubleheader against the Browns on September 30. Had the Browns swept, there would have been a one-game playoff in Detroit for the pennant.19

The first game of the twin bill is arguably the most well-known game played in 1945. It was raining in St. Louis for the 10th straight day on September 30.20 The field was a quagmire, and the game probably would not have been played if the pennant were not at stake.21 The contest commenced after a 50-minute delay, with Virgil Trucks, just a few days after being discharged from the Navy, starting for the Tigers.22 Trucks allowed a run in the bottom of the first, but the Tigers took the lead with single tallies in the fifth and sixth innings. The Browns scored single runs in the seventh and eighth to take a 3–2 lead going into the ninth. Pete Gray, the Browns’ one-armed outfielder, scored the go-ahead run in the eighth. Nels Potter, the starter for the Browns, was still pitching in the ninth. A single, fielder’s choice, bunt, and intentional walk brought Greenberg to the plate as a pinch-hitter with the bases loaded. Greenberg described what happened next:

As he wound up on the next pitch, I could read his grip on the ball and I could tell he was going to throw a screwball. I swung and hit a line drive toward the corner of the left-field bleachers. I stood at the plate and watched the ball for fear the umpire would call it foul. It landed a few feet inside the foul pole for a grand slam. We won the game, and the pennant, and all the players charged the field when I reached home plate and they pounded me on the back and carried on like I was a hero.23

The Browns failed to score in the bottom of the inning, and the second game was not played.

From a modern perspective, another interesting aspect of the story is that the Tigers would have won the pennant even if they had lost the first game. The weather conditions and darkness would have precluded the second game being played. There was no rule at the time saying a team had to complete its schedule, even if any unplayed games had bearing on the pennant race. Since the second game could not have been played, even with a loss, the Tigers would have won the pennant by a half game.24

THE FINAL SEVEN WEEKS IN THE NATIONAL LEAGUE

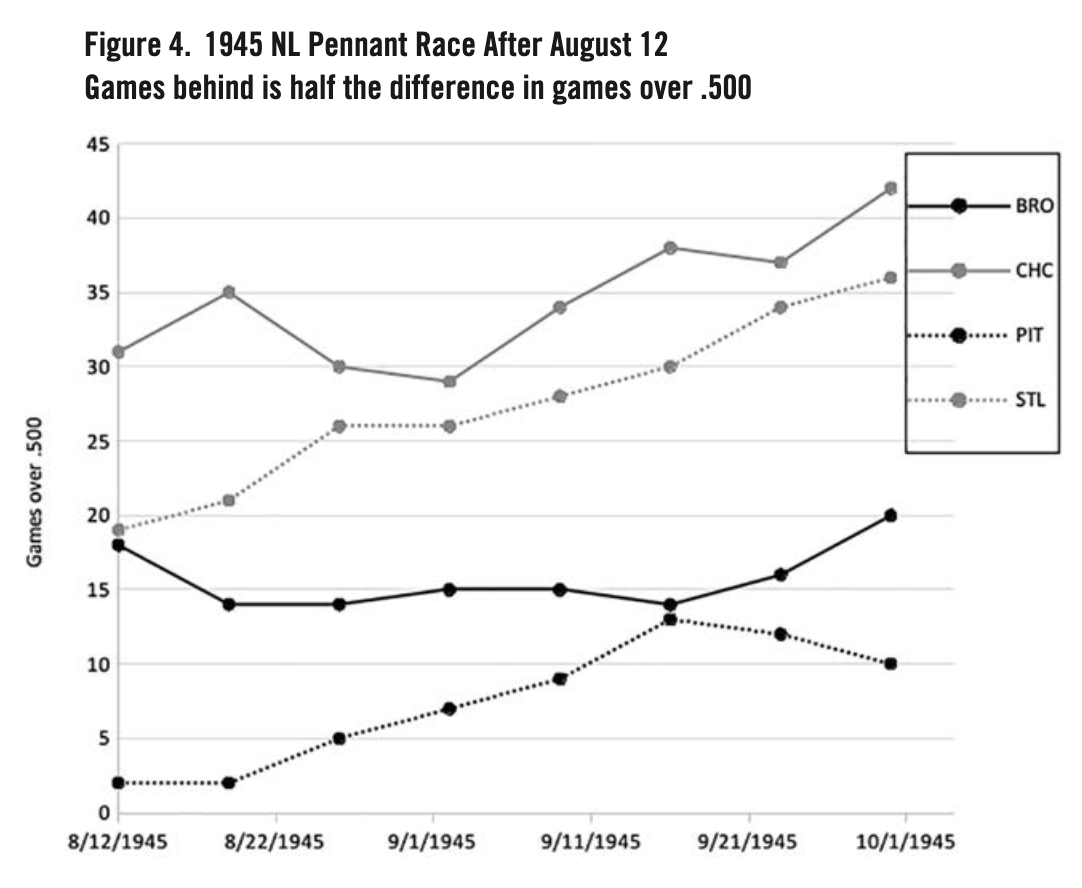

The last seven weeks of the pennant race in the NL are shown in Figure 4, which shows that the Cubs had a comfortable lead over the Cardinals and the Dodgers on August 12. Brooklyn went 2–8 over their next 10 games, including losing three out of four to the Cubs at Ebbets Field, which essentially ended their bid for the pennant. Chicago and St. Louis faced off seven times in late August and early September. The Cubs got swept in three games at home, and then lost three out of four in St. Louis. This put the Cardinals just 11⁄2 games behind Chicago after play on September 2.

Both teams had favorable schedules in September. The Cardinals were at home almost the entire month before finishing the season with six away games starting on September 25. The Cubs had an 18-game home stand from September 3–17, with eight away games in the latter part of the month. They both took advantage of playing at home. The Cardinals won seven straight from September 6–12. But unfortunately for St. Louis, Chicago went 13–4 from September 3–16 to increase its lead to four games after play on Sunday, September 16.

A Cardinals victory and a Cubs loss on the 17th meant the teams were separated by three games as the Cubs went to St. Louis for a three-game series starting on the 18th. The two teams were also scheduled to play two games in Chicago the following week. The Cardinals had good reason to be confident that they could catch the Cubs. The three-time defending NL champs were 13–4 against Chicago for the season, and had won three of their last four games going into the September 18 contest. St. Louis won the game on the 18th to close to within two games.

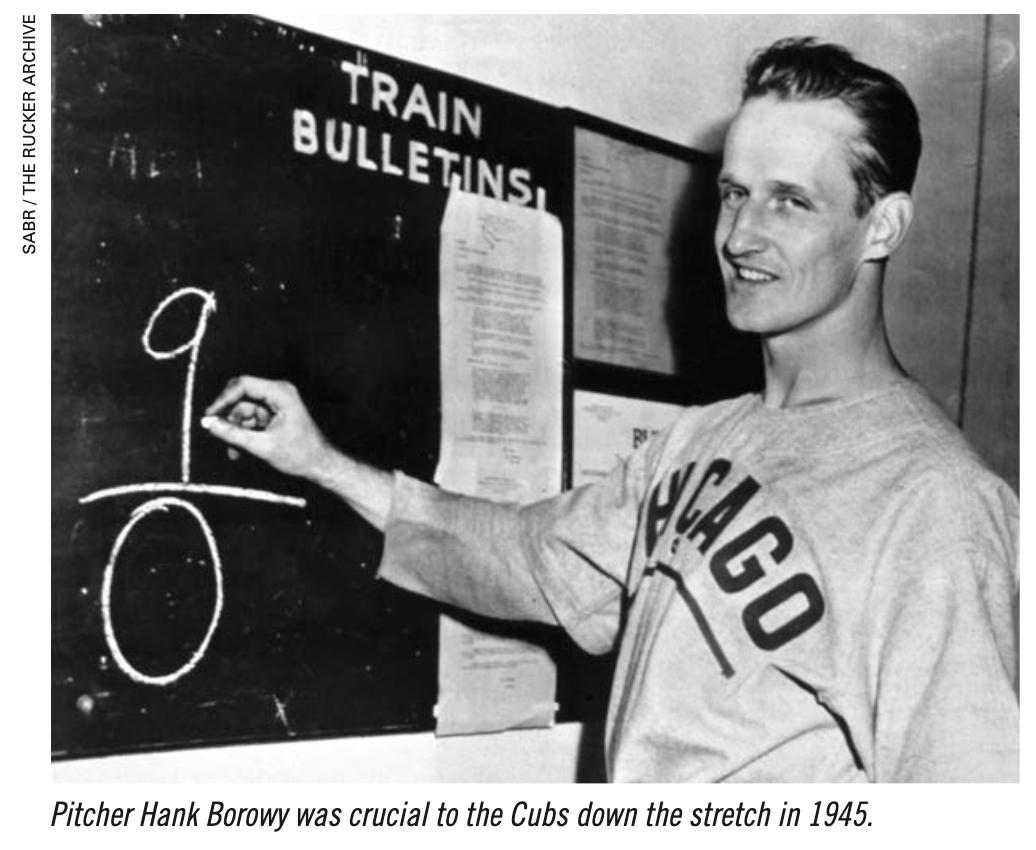

A late-season acquisition by the Cubs had a big impact on half of the remaining games between the two clubs. The Cubs purchased pitcher Hank Borowy from the Yankees for $97,000 (an immense figure at the time) on July 27.25 Borowy, who went 108–82 in a 10-year major league career, is not well remembered today, but he was the ace of the Yankees staff in 1944. He had 10 wins for the Bronx Bombers in 1945 before he was sent to the Cubs, and he made an immediate impact on the NL pennant race. Borowy went 8–2 with a 1.96 ERA for Chicago before starting against the Cardinals on September 19. George Dockins was on the mound for St. Louis for the contest on the 19th. The game was a classic pitchers’ duel. The Cubs put a runner on second in the first and fourth innings, but failed to drive in the run. The Cardinals loaded the bases in the sixth inning but Borowy ended the threat by inducing a double play, so the game was scoreless after seven innings. In the home half of the eighth, Borowy walked Dockins (who was batting ninth) with one out. The Cardinals hurler scored on consecutive singles to put St. Louis ahead, 1–0, entering the ninth.

Dockins got the Cubs leadoff hitter in the ninth to ground to third, but an error by St. Louis third baseman Whitey Kurowski allowed Don Johnson to reach first.26 A sacrifice bunt by Peanuts Lowrey put pinch-runner Ed Sauer in scoring position. The Cubs were down to their last out after Phil Cavarretta popped out. With one more out the Cardinals would be within a single game of the Cubs. But a single by Andy Pafko drove in the tying run, and the game went to extra innings after Borowy set the Cardinals down in order in the bottom of the ninth. The Cubs scored three times in the top of the 10th and won the contest 4–1, with Borowy again retiring the side in order in the home 10th.27

With the benefit of hindsight, the race likely turned on the outcome of the game on the 19th. St. Louis won the third game of the series, but Borowy’s victory meant the Cubs lead was still two games with just eight games left in the season. St. Louis trimmed a half game from that lead entering a two-game series in Chicago the next week. A sweep would put the Cardinals in first place with five games remaining. But St. Louis would have to beat Borowy in the first game to make that happen.

Borowy was not as sharp as he had been in the last game, and the Cardinals led 3–2 in the middle of the seventh. But the Cubs pushed four runs across the plate in the bottom of the inning to take a 6–3 lead. St. Louis made it close with two runs in the eighth, but couldn’t get the hit that would tie the game. The Cardinals won the second game of the series, but for the second consecutive week, Borowy had notched the win against St. Louis in a crucial game.

The Cubs won their last five games of the season to win the pennant by a final margin of three games over the Cardinals. Borowy was 11–2 with a 2.13 ERA after he was acquired by Chicago. It needs to be mentioned that Borowy was not the only Cubs pitcher to make a big contribution to securing the pennant. The wartime player shortage compelled Chicago to turn to 38-year-old Ray Prim in an effort to bolster their rotation. Prim responded with a career year that was topped by a tremendous run during the final three months of the season. From July 6 to the end of the season Prim went 11–4 with a 1.27 ERA. His 2.40 ERA overall led the league.

CONCLUSION

The main point of this article is to describe the 1945 pennant races, not the 1945 World Series. That said, it is appropriate to conclude the article with a brief description of what happened after those two exciting races.

The playoff structure in major league baseball was very simple before 1969. The pennant winners faced off in the World Series. So after two tight pennant races, Chicago, with a 98–56 record, played the 88–65 Tigers in the Fall Classic. Detroit’s chances against the Cubs had been boosted by the September return of Vigil Trucks, who started two games against the Cubs in the World Series, winning one and getting a no-decision in the other. Given the drama of the two pennant races, it seems appropriate that a World Series between these two teams would come down to a winner-take-all game. The Tigers scored five runs in the first inning of Game Seven and went on to win the contest 9–3. It was the second World Series victory for Detroit. The Tigers had won their first championship with a victory over the Cubs in 1935. Finally, it would be a dereliction of duty to summarize the 1945 World Series and not mention one of the most famous animals in baseball history. For over 70 years, until the Cubs reached the promised land in 2016, many Chicagoans believed that a goat was preventing the Cubs from winning the World Series. Legend has it that a Chicago tavern owner cursed the team when he and the goat he had brought to Game Four of the 1945 World Series were thrown out of the ballpark. The Curse of the Billy Goat was born. But there is more to the legend than that. Glen Sparks tells the rest of the story in SABR’s Wrigley Field: The Friendly Confines at Clark and Addison. The author was part of a small group of SABR members who had the opportunity to visit the Billy Goat Tavern during the 2023 SABR convention in Chicago.

DOUGLAS JORDAN is a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University in Northern California. He has been a regular contributor to the BRJ since 2014. He runs marathons and plays chess when he is not watching or writing about baseball. You can contact him at jordand@sonoma.edu.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to two anonymous peer reviewers. Their suggestions significantly improved the final product.

Notes

1 Bertram D. Hulenspecial, “All Racing Banned on Call of Byrnes to Aid War Effort,” The New York Times, December 24, 1944, 1.

2 Dan Daniel, “Washington Doesn’t Plan to Halt Game,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1945: 1.

3 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 16.

4 “50 Percent of 4-F’s Accepted,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1945: 1.

5 “Greenest of All Green Lights for Game,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1945: 10.

6 John Klima, The Game Must Go On, (New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2015), 344.

7 Renwick W. Speer, “Wartime Baseball: Not That Bad,” Baseball Research Journal 12 (1983), accessed May 15, 2023.

8 Four more teams have won 100 or more games in three consecutive years since the Cardinals did it. They are the 1969-71 Baltimore Orioles, the 1997-99 Atlanta Braves, the 2002-04 New York Yankees, and the 2017-19 Houston Astros.

9 The 1921 and 1922 World Series were also played in one stadium, the Polo Grounds in New York City.

10 Gregory H. Wolf, “Mort Cooper,” SABR BioProject, accessed May 15, 2023.

11 Klima, The Game Must Go On, 269.

12 Klima, 324.

13 Noah Scott, “Knuckleheads: The 1945 Senators and the First All-Knuckleball Rotation,” Pitcherlist, July 20, 2020, https://www.pitcherlist.com/knuckleheads-the-1945-senators-and-the-first-all-knuckleballrotation/, accessed August 25, 2023.

14 Scott.

15 Steven P Gietschier, Baseball: The Turbulent Midcentury Years (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2023), 235.

16 Dan Daniel, “Fewer U.S. Calls, Some Will Return,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1945: 1.

17 Greenberg injured his ankle sliding into second base on September 9. The injury was severe enough that he could not start in the crucial series against Washington. He did pinch-hit three times during the Washington series. See Klima, The Game Must Go On, 364.

18 Rob Neyer, “A Last Great Season: The Senators in 1945,” ESPN, March 14, 2002, https://www.espn.com/page2/wash/sZ2002/0314/1351582.html, accessed May 28, 2023.

19 Neyer, “A Last Great Season…” Neyer writes, “So as the last day of the season dawned, the Tigers still owned a one-game lead over the Senators heading into a twin bill against the third-place Browns in St. Louis. Win either game, and they would clinch the pennant. Lose both, and the Tigers would head back to Detroit, where Dutch Leonard was already waiting to pitch in a one-game playoff for the American League pennant.”

20 Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 34.

21 Fred Lieb, “Browns Again Shape History in Final Game,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1945: 27.

22 Neyer, “A Last Great Season.”

23 Neyer.

24 Neyer.

25 The details of the Yankees-Cubs Borowy transaction sound like a soap opera. Yankees GM Larry MacPhail sold Borowy to the National League Cubs deliberately so that the American League Nationals (and their owner, Clark Griffith) would not get the pitching help they desperately needed down the stretch. It was also done to make it harder for the Cardinals to catch the Cubs in revenge for the Cardinals victory over the Yankees in the 1942 World Series. See Klima, The Game Must Go On, 326-27.

26 Frederick G. Lieb, “Hard-Fighting Cards Open Hard-Way Drive,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1945: 8.

27 Play-by-play for this game is not complete. The incomplete Retrosheet account was used to describe the game action. “Chicago Cubs 4, St. Louis Cardinals 1,” Retrosheet, https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1945/B09190SLN1945.htm, accessed June 9, 2023.