The 1954 Dixie Series

This article was written by Kenneth R. Fenster

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

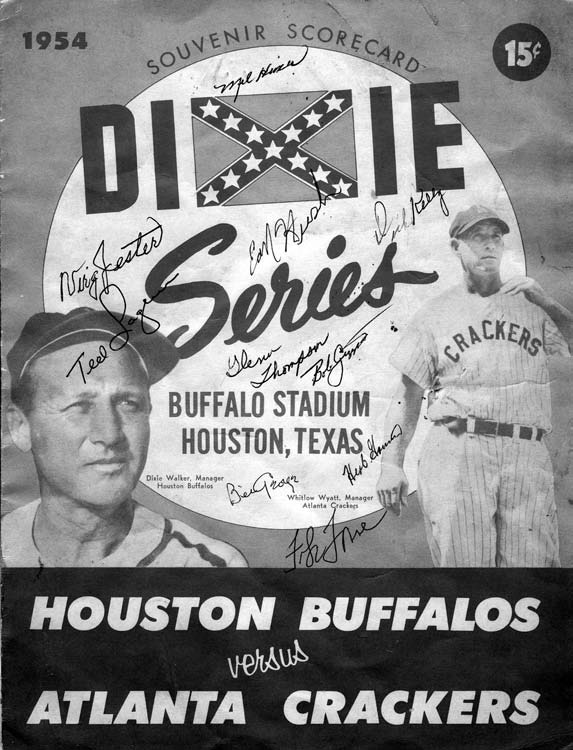

On September 21, 1954, the Atlanta Crackers, champions of the Double A Southern Association, and the Houston Buffaloes, champions of the Double A Texas League, squared off in Atlanta’s venerable Ponce de Leon Park in the first game of the 32nd annual Dixie Series, the South’s version of the World Series.1 Houston finished the regular season in second place one game out of first and then defeated Oklahoma City (4 games to 1) and Fort Worth (4 games to 1) in the playoffs to earn the honor of competing for the championship of Southern baseball.

For the Crackers something more—something much more—than becoming the undisputed champion of Southern baseball was at stake in the Dixie Series. Atlanta had already captured three of the four prestigious events its league offered. The Crackers won the annual All-Star Game 9–1, finished first in the regular-season standings two games ahead of New Orleans, and had then defeated Memphis (4 games to 2) and New Orleans (4 games to 1) to take the playoffs. A victory in the Dixie Series would give the Crackers a clean sweep of everything the Southern Association offered, allowing the club to join the 1938 Crackers as the only teams in history to win the Southern Association grand slam.2

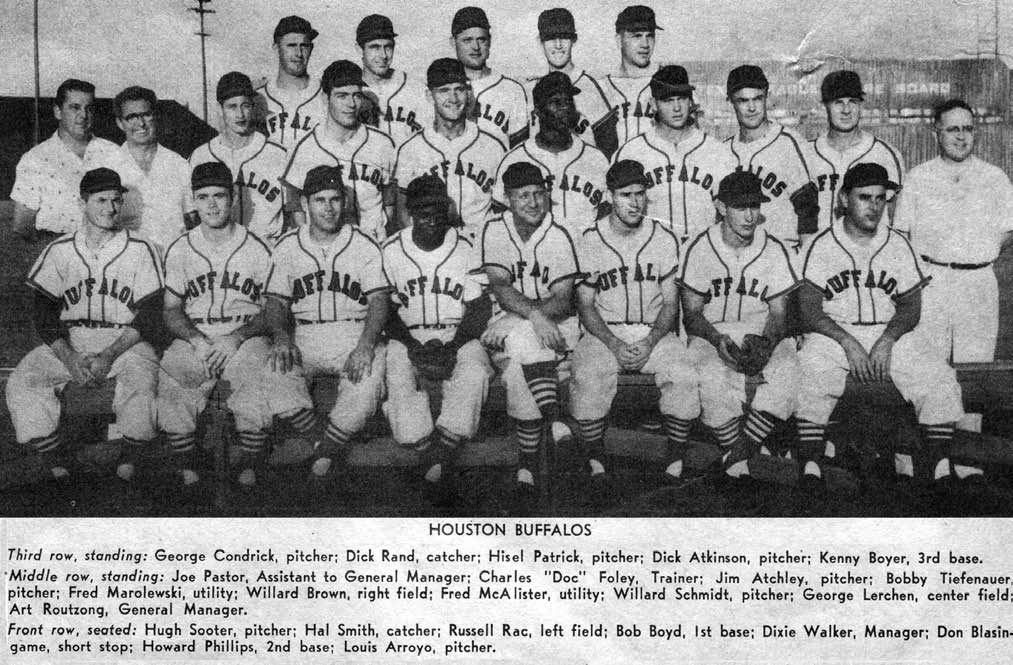

Offensively, the Houston ball club led the Texas League in runs scored, hits, total bases, stolen bases (by a huge margin), RBI, and batting average. The Buffaloes also grounded into the league’s fewest double plays.3 The everyday lineup boasted six players who batted more than .300. Houston finished last in the league in home runs, but the team had remedied this deficiency with the late-season acquisition of former Negro League slugger Willard “Home Run” Brown.4 Playing for Dallas and Houston, he batted .314 with 35 home runs and 120 RBI. Brown, an outfielder, and “the Killer B’s,” three future major-league starters, first baseman Bob “The Rope” Boyd (.321, 7, 63), third baseman Ken Boyer (.319, 21, 116, and 29 SB), and shortstop Don Blasingame (.315, 5, 53, and 34 SB), drove Houston’s potent attack.

Houston’s four starting pitchers were Willard Schmidt (18–5, 3.69 ERA), Hisel Patrick (10–3, 3.77 ERA), Luis Arroyo (8–3, 2.35 ERA), and Hugh Sooter (14–13, 3.28 ERA). Among league pitchers with 10 or more decisions, Schmidt led in winning percentage, Patrick was second, and Arroyo was fifth. Schmidt, a power pitcher, finished third in the league in strikeouts with 186, and Arroyo, a screwball specialist, fanned 130 in only 115 innings. Arroyo, promoted to Houston in the middle of the season from the Class A Sally League, pitched the only no-hitter in the Texas League in 1954. Houston’s ace reliever was future major leaguer Bob Tiefenauer, a knuckleball pitcher. According to Houston Post sportswriter Clark Nealan, Tiefenauer preserved many small leads during the season and was indispensable to the success of the Buffaloes.5

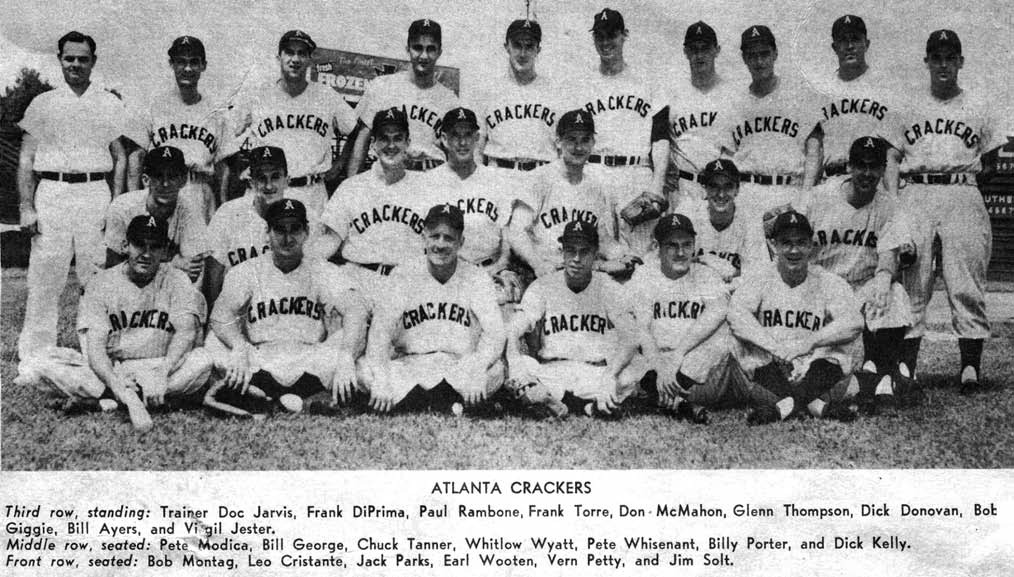

Atlanta’s offense depended on the power hitting of its outfielders, Bob Montag (.305, 39, 105) and future major leaguers Pete Whisenant (.285, 20, 94) and Chuck Tanner (.323, 20, 101). When one of them hit a home run, the Crackers usually won the game.6 Montag’s 39 home runs were second in the league and set an Atlanta franchise record for most circuit clouts in a season. He led the association in walks with 122 and in on-base percentage at .450. He also led the league in strikeouts with 121. Montag was third in the circuit with 293 total bases and second in slugging percentage at .648. Tanner was second in the league in total bases with 311 and second in hits with 192.7 Second baseman Frank DiPrima (.316, 12, 68) and first baseman Frank Torre (.294, 9, 74) also contributed to the Cracker attack. They, especially Torre, anchored the infield defense. Torre played 112 consecutive games and handled his first 1,006 chances before making an error, establishing two Southern Association records for defensive excellence.8 Longtime Atlanta sportswriter Ed Danforth described him in one of his regular columns as the finest fielding first baseman in the history of the Southern Association.9

For most of the season, Atlanta had only two reliable starting pitchers, Leo Cristante (24–7, 3.59 ERA) and Dick Donovan (18–8, 2.69 ERA), a future major league star. Cristante led the league in victories by a wide margin and in winning percentage. Donovan, who did not join the team until mid-May, when the Detroit Tigers returned him to Atlanta, was second in the league in ERA and tied for second in the league in wins. Once the moody and capricious Donovan had learned to control his volatile temper on the mound and added the slider to his repertoire, he became the best pitcher in the league.10 In the final two months of the season, Donovan compiled a stellar record of 11 wins against only two losses. He won many crucial games for the Crackers, and the Atlanta sportswriters frequently referred to him as the team’s “money pitcher.”11 His teammates recognized his contributions to their success when they selected him as the club’s most valuable player.12

In late July, the Crackers acquired a third dependable starting pitcher when Triple A Toledo sent the team Glenn Thompson. When he joined the Crackers, the 6′ 5″ Thompson had a blazing fastball but little control. He stumbled in his first four starts with the Crackers, winning one and losing three with 15 walks in 20 innings and an ERA of 5.40. Then in mid-August he harnessed his speed, and for the final few weeks of the season, he overpowered Southern Association hitters. In a game against New Orleans, he used his fastball to fan 19 batters, establishing a Southern Association record for most strikeouts by a pitcher in a nine-inning game.13 In his last five starts of the regular season, Thompson pitched five complete games, went 5–0, gave up only 34 hits and eight runs, and struck out 49 batters.

Atlanta’s fourth starting pitching slot rotated among Bob Giggie, Bill George, Dick Kelly, and Virgil Jester. None of them pitched well consistently. They combined for 68 starts during the season, compiling a mediocre record of 25 wins and 27 losses. The team’s top relief pitcher was another future major-league star, Don McMahon. In 46 appearances (all but one in relief), he hurled 91 innings, struck out 90 batters, and won eight and lost five with a 3.56 ERA.

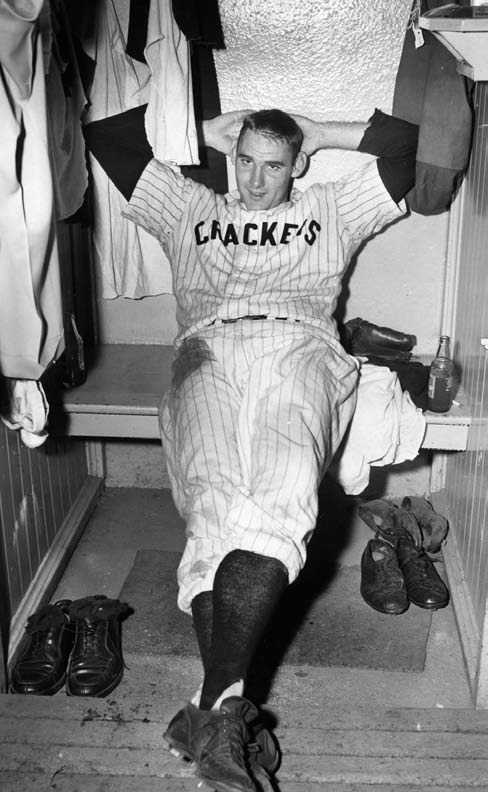

Jim Solt’s lone hit in the 1954 Dixie Series was one of the most memorable in Atlanta Crackers history. (DENNIS GOLDSTEIN COLLECTION)

As a team, Atlanta was greater than the sum of its individual parts. At catcher the Crackers had an excellent platoon, with the right-handed hitter Jim Solt and the left-handed hitter Jack Parks. Almost always batting in the lower third of the order, they combined to hit 17 home runs, drive in 84 runs, score 68 runs, and bat .317.14 Billy Porter, the starting shortstop, was equally adept at third base. Donovan was both a star pitcher and an excellent hitter. He pinch-hit regularly, and he even started a few games in the outfield to take advantage of his powerful bat. In 114 regular-season at-bats, he hit .307 with 32 RBI and 17 extra base hits, including 12 home runs, which tied a league record for most homers in a season by a pitcher.15

The two most versatile players on the team were super utility man Paul Rambone and Earl “Junior” Wooten. The fiery and tempestuous Rambone appeared in 133 games and accumulated 481 at-bats without having a regular position. On numerous occasions, he played more than one position during the same game. For the season, Rambone played 82 games at shortstop and 25 games at both third and second base. He also played both corner-outfield positions, first base, and even catcher. At the plate, Rambone contributed 89 runs scored and 52 extra base hits, including 19 home runs.

Wooten, the club’s elder statesman and leading comedian,16 had played with the Washington Senators in 1947 and 1948 and had already spent a decade in the Southern Association. The decline of his offensive skills precluded him from a starting berth on the team, but he remained a superb defensive first baseman and outfielder.17 When he substituted for the slick-fielding Frank Torre at first base, the Crackers lost very little defensively. When Wooten replaced the weak-fielding and weak-throwing Montag in the late innings of close games, his most frequent role on the club, the Crackers had the best defensive outfield in the league: Whisenant in left, Wooten in center, and Tanner in right.18 Wooten also pitched in emergency situations, pitched batting practice regularly, coached first base, and managed the team whenever manager Whitlow Wyatt was unavailable.

The 1954 Dixie Series was full of irony.19 Atlanta made history at the beginning of the season when it integrated its team and its league. The Crackers broke the color line in the venerable, tradition-rich Southern Association when outfielder Nat Peeples, a former Negro League player, made the team’s opening-day roster. Peeples appeared in the first game of the season, playing in Mobile, Alabama, as a pinch hitter. He started the next game in left field. Two days later, he returned to Atlanta to open the home season. But before he played in a regular-season game in Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park, the Crackers demoted him to Jacksonville, in the Class A South Atlantic League. Peeples never again played in the Southern Association. He was the first and only African American to play in the league.20

Houston also integrated its team in 1954. In the middle of the season, the club purchased the contract of first baseman Bob Boyd, another former Negro Leaguer, from the Chicago White Sox, and later the team acquired Willard Brown from the Dallas Eagles of the Texas League. Houston manager Dixie Walker attributed much of the team’s success to Boyd and Brown, who became extremely popular with Houston fans, who affectionately nicknamed them Mr. Boom and Mr. Bam.21 So even though the Crackers had integrated at the beginning of the season, when Boyd and Brown played in the opening contest of the Dixie Series on September 21, 1954, they became the first African Americans to play in an official game at Ponce de Leon Park.22

The 1954 Dixie Series was more than just a championship playoff between competing teams and leagues. It also formed the backdrop to an intense personal drama and rivalry between the two managers, Houston’s Dixie Walker and Atlanta’s Whitlow Wyatt. They had been teammates for six years with the Brooklyn Dodgers, including the pennant-winning 1941 squad. The two men were also the closest of friends. Almost immediately after Earl Mann, the Crackers’ owner, hired Walker to manage the 1950 Atlanta Crackers, Walker lured Wyatt out of retirement to serve as his pitching coach and chief assistant. Together, they led the 1950 Crackers to a Southern Association pennant. They remained at the helm of the Crackers for two more years, finishing sixth in 1951 and second in 1952.23 Collaborators no longer, they now confronted each other as the fiercest of rivals.

Even before either Houston or Atlanta had won their leagues’ playoffs, Clark Nealon, sports editor of the Houston Post, yearned for a Walker-Wyatt showdown in the Dixie Series. In his regular column, Nealon wrote: “Should the Buffs make it to the Dixie Series, nothing would please Manager Walker more than for Atlanta to win the Southern Association playoff.”24 The Atlanta papers also relished the personal confrontation between the two managers brewing in the upcoming Dixie Series. Two days before the first game, an anonymous author wrote in the Atlanta Journal: “As the Texas League season sizzled to a stop, Walker envisioned a triumphant return to Atlanta, scene of his first managerial assignment in 1950. It’s no secret that the soft-spoken Alabaman yearns to send his Buffs against his old club, now managed by Wyatt, a former Brooklyn teammate. He wired Whit his personal congratulations immediately after Atlanta clinched its playoff berth. Plainly, a Houston-AtlantaWalker-Wyatt series would have immense appeal for all concerned.”25

The editorial boards of both Atlanta papers made the dramatic, personal rivalry between Walker and Wyatt the central theme of the upcoming games. According to the editors of the Atlanta Journal: “For the first time in many years, there will be a real rivalry between Atlanta and the Texas League champion. Houston is managed by Dixie Walker, late of the Crackers. And of course Walker’s former assistant, manager Whit Wyatt, now leads Atlanta.”26

On the day of the first game of the Dixie Series, the Atlanta Constitution editorial board wrote: “Technically it is Atlanta versus Houston and the Southern Association versus the Texas League for the championship of the whole wide South. Locally it is all that and something more. Houston’s boss is Dixie Walker, formerly the manager of the Crackers. Whitlow Wyatt, who has piloted Atlanta through a great season, was Walker’s assistant when he was in Atlanta. When an ex-hero returns to his old home stand as an enemy, there’s more at stake than just prestige, and usually there’s blood in more than one pair of eyes. . . . It’s not only a matter of winning the Dixie, but stomping old Dixie while we’re at it.”27

Even the Constitution’s editorial cartoonist, Clifford Baldowski, got caught up in the drama of the Walker-Wyatt showdown. His cartoon of September 22, 1954, appropriately titled, “When Old Friends Get Together,” shows Walker and Wyatt soaring high above Ponce de Leon Park tenaciously clutching the 1954 Dixie Series pennant while they clobber each other with baseball bats.28

1954 Atlanta Crackers (COURTESY OF KENNETH FENSTER)

On September 20 and 21, Crackers owner Earl Mann placed large ads on the first page of the Constitution’s sports section, promoting the first two games of the Dixie Series. Game time was 8:15 P.M. Box seats cost $2.60; grandstand seats a more modest $1.85; bleachers went for $1.25. Children could sit in the grandstand and the bleachers for $1.00 and $0.50, respectively. Patrons could purchase tickets at the Ponce de Leon box office or at Muse’s clothing store in downtown Atlanta. A large but not sell-out crowd of 11,495 attended the first game of the Dixie Series on September 21, a balmy Tuesday night.29

The game drew the largest African American attendance of the season to Ponce de Leon Park, and the Negro grandstand and bleachers overflowed with a standing-room-only crowd. Blacks also flocked in great numbers to Game 2 of the series. They came not to watch the Crackers but to see and cheer Houston’s two African American players.30

Houston won the first two games of the series convincingly. The Buffaloes took the opener 10–4. Left-hander Luis Arroyo hurled a complete game and gave up only seven hits. The Killer B’s had three extra-base hits, scored five runs, and drove in three. Outfielder Fred McAlister hit a long three-run homer in the sixth inning to put the contest out of reach. Houston trounced the Crackers in the second game, 7–2.

Willard Schmidt gave a masterful pitching performance, and the Killer B’s continued their hot hitting with two more extra-base hits, four runs scored, and two driven in. In both games, Atlanta’s pitching collapsed. Glenn Thompson started the first game and lasted less than two innings, yielding five hits and four runs. He and five other Atlanta pitchers walked 11 batters. In the second game, Leo Cristante surrendered seven hits and five runs in two innings. Schmidt limited the Crackers to two hits and none after the second inning. He struck out 11 batters in the game that he, his catcher, and his manager agreed was his best outing of the year.31

In these two contests, the Buffaloes outperformed the Crackers—whom Houston sportswriter John Hollis described as “listless”—in every facet of the game.32 Houston’s vastly superior speed impressed the sportswriters from both cities as that team’s single greatest advantage over Atlanta. In both games, Houston dazzled Atlanta with its aggressiveness on the bases. The Buffaloes took the extra base on hits to the outfield, stretching singles into doubles and doubles into triples. Twice Houston scored on wild pitches.

The highlight of the team’s running attack was Bob Boyd’s “ridiculously easy steal of home” in Game 2. As Atlanta left hander Bill George went into an elaborate windup, Boyd dashed for home from third. He was already three-fourths of the way to the plate before the Cracker hurler had even released the ball. The ball arrived so late that catcher Jack Parks made no effort to tag the sliding Boyd.33 Houston’s daring base running reminded Atlanta sportswriter Bob Christian of the Gas House Gang, and Whitlow Wyatt pondered quizzically: “Those guys fly, don’t they?”34 Because of Houston’s speed, Ed Danforth wrote in his regular column that Atlanta could not win the series and should surrender. He asserted:

On what they showed here, Dixie Walker’s club could have won the Southern Association pennant by 10 games. No club in our league was nearly that fast. . . . On speed alone, Houston would have run our league ragged. . . . Bob Boyd . . . can outrun any of the Crackers or the [New Orleans] Pelicans. . . . The way they [the Buffaloes] took out after the Crackers in the first three innings it looked as if the best strategy was to pull the light switch and start all over again. Whitlow Wyatt has a game club with a lot of power, but beside this Houston crew they were wearing gum boots. . . . When this Dixie Series came up they [the Crackers] ran into a club that was just too good for them. They must be given “A” for effort, but to insist on pinning the shoulders of that fast-breaking Houston club is asking too much.35

The Crackers and Earl Mann, however, remained optimistic. When the team left for Houston for the next three scheduled games, the marquee at Ponce de Leon Park read, “Atlanta vs. Houston, September 27th.”36

The series now shifted to Houston’s Buffalo Stadium, where Houston had not lost a three-game series since July.37 Down two games to none, the Crackers faced a must-win situation in Game 3. Behind the team’s year-long reliables, Dick Donovan and Bob Montag, Atlanta defeated the Buffaloes 7–4. Donovan pitched a complete game and contributed with his bat, collecting two hits, a walk, two RBI, and one run scored. Atlanta banged out 13 hits, more than the team’s combined total in the first two games.

For the first time in the series, the Crackers scored first, plating two runs in the third inning on Rambone’s double, Donovan’s walk, Porter’s sacrifice, and Torre’s single. Three times during the game, Houston came from behind to tie the score, with the Killer B’s doing most of the damage. They scored three runs and knocked in two more. Then in the eighth inning, Montag hit a solo home run that put the Crackers ahead for good.

The key play in the game came in the bottom of the ninth inning. With the score 7–4, the left-handed Earl Wooten went into the game to play center field as a defensive replacement for Montag. Regular center fielder Whisenant moved to left field, and Montag, the starting left fielder, came out of the game. Wyatt had used this strategy in the late innings of close games frequently during the season, and never was the move more important than in this game.

With one out and a runner on first base, Houston outfielder George Lerchen, a left-handed hitter, smashed a terrific slicing line drive headed for deep left-center field. Wooten had shaded Lerchen toward right field, so he was a long way from the ball. Being left-handed gave Wooten a crucial advantage in making the play.

He explained: “I remember that ball. It went out and I thought I could catch it all the way. I did. I ran toward left field. Yes I did, because that’s the one that my glove hand is on, that side. That gave me a little more leverage over on my right side. I had my glove on my right hand, so I ran toward left field and that helped a lot. When the ball came off the bat, I thought I had it all the way.”38

The sportswriters from both cities lavished effusive praise on Wooten’s catch. Dick Freeman of the Houston Chronicle described it as “one of the best fielding plays ever seen in Buff stadium.” Jesse Outlar of the Atlanta Constitution called it “a miracle catch. . . . No one thought Wooten could make the catch—but he did—a sensational diving, one-handed stab.” And according to Atlanta sportswriter Bob Christian, when Lerchen hit the ball, “Wooten took off like a coyote and never gave up on it. When he saw he might not catch it, he made a long, diving effort and caught the ball. He rolled over a couple of times, but still got up in time to keep the runner from advancing. That was the ball game. The crowd began to jam the exits.” Christian ranked this catch “as the best ever in the Southern Classic.”39

1954 Houston Buffalos (COURTESY OF KENNETH FENSTER)

In Game 4, after Atlanta starting pitcher Dick Kelly faced three batters and gave up three hits and one run, Wyatt replaced him with Bob Giggie, who held the Buffaloes scoreless for the rest of the frame. The Crackers plated two runs in the third inning to take the lead. Houston tied the game in the bottom half of the third on Bob Boyd’s solo home run and then scored three runs in the sixth off Atlanta’s ace relief pitcher, Don McMahon, to win the game 5–2. The Killer B’s scored all of Houston’s runs, had four RBI, and stole three bases. In the first three innings, Atlanta left six men on base, wasting several opportunities to score. In the last six innings, Atlanta had only two hits, both meaningless singles. With Houston now enjoying a commanding three-to-one lead in the series and with Arroyo and Schmidt available to pitch Games Five and Six, Atlanta sportswriter Jesse Outlar was ready to concede defeat.40

Game 5 featured a rematch of Game 1’s starting pitchers, Luis Arroyo for Houston and Glenn Thompson for Atlanta. The Crackers scored the only run of the game in the first inning when Wooten raced across the plate on Pete Whisenant’s broken-bat, bloop single.41 Thompson, so ineffective in Game 1, pitched brilliantly, using his blazing fastball to overpower the hard-hitting Buffaloes. He yielded a measly three hits—two to Killer B Bob Boyd—and he struck out 11. Thompson allowed only two Houston runners to reach as far as second base.

The Atlanta pitcher got into trouble only once in the game. In the bottom of the eighth, he walked the number-eight hitter to start the inning. After a wild pitch advanced the runner to second base, Thompson walked the pitcher. With Houston having the potential winning run on base and the top of the order coming to bat, the Crackers faced imminent elimination.

But Thompson remained poised and responded to this pressure-packed situation with great clutch hurling. Houston leadoff hitter Don Blasingame bunted Thompson’s first two pitches foul. The Atlanta pitcher ran the count full and then induced Blasingame to hit a weak pop-up to shortstop. Thompson also went to a full count on the next batter, second baseman Howard Phillips, a .306 hitter during the season, and then struck him out. The third hitter in the Buff lineup was the dangerous Ken Boyer.

With the raucous, partisan crowd cheering louder for Boyer on every pitch, Thompson ran the count full yet again. Then Thompson retired Boyer on a long but harmless fly to Pete Whisenant in left field. Jesse Outlar thought Thompson’s performance was the best in the history of the Dixie Series, and Earl Mann believed it was the finest he had seen in his entire 25-year career as a minor-league executive.42

With the victory in this tension-filled must-win game, the Crackers forced the series to return to Ponce de Leon Park for at least one more contest. Sunday, September 26 was an off day. Game 6 was scheduled for Monday night, and Game 7, if necessary, would be played on Tuesday. Thompson’s sensational victory pumped new life into the team, and the Crackers were confident they could win the next two games.

The players spent the off day relaxing at a steak dinner Earl Mann gave them at Aunt Fanny’s Cabin, a popular Atlanta restaurant. Dick Donovan, known for his gregarious, fun-loving ways and good sense of humor off the mound, came to the banquet unconcerned about his scheduled start in the upcoming crucial Game 6 of the series.43 He and his pal and roommate Bill George wore big cowboy hats, chomped on fat cigars, and lived it up.44

Houston also anticipated victory. In fact, the Buffaloes arrived in Atlanta on Sunday so confident that they would win Game 6 and thus the series that they made hotel reservations for only that night. They checked out of their rooms prior to coming to the ballpark on Monday, convinced that the Crackers would not force a Game 7.45 Such hubris— so reminiscent of ancient Greek tragedy—rarely goes unpunished.

When Atlanta took the field to start Game 6, the crowd of 10,447 gave the team a tremendous ovation. The Crackers did not disappoint their fans. Starting pitcher Dick Donovan, whom Bob Christian christened immediately after the game as “the greatest thing in Atlanta since sliced bread,” pitched and hit the Crackers to a 6–2 triumph and a tie in the series at three victories apiece.46 The Atlanta pitcher, according to Christian, brought to the game an indomitable will to win. Donovan attributed the victory to the effectiveness of his slider.47 He hurled a complete game, giving up only seven hits and shutting down the Killer B’s, limiting Houston’s most dangerous hitters to three hits in 13 at-bats, no runs scored, and one RBI. Donovan struck out eight and walked only one, and that was an intentional pass. At bat, Donovan had a double, was hit by a pitch, and scored both times he reached base.

The Crackers rallied against Houston’s ace pitcher, Willard Schmidt, in the fourth inning to plate five runs and overcome a one-run deficit. Third baseman Vern Petty, who had seen very little playing time since suffering a freak off-the-field injury48 in mid-August, delivered a key blow in the inning, a two-run double. As Petty pulled into second base and catcher Jack Parks and Donovan crossed the plate to give the Crackers a one-run lead, the large crowd cheered loud and long. Later in the inning, Pete Whisenant drove in two more runs with a triple to right field. With this sizeable lead, Donovan coasted the rest of the way.

After the game, the Houston players stoically filed into their locker room and then went back to their hotel, where they had to re-register for rooms. The Crackers had spoiled their plans for an early return home. The Crackers stormed their locker room full of joy and jubilation. They chanted, “Sixty instead of forty!”—a reference to the percentage of the first four games’ gate receipts that the players on the winning and losing teams received for the series.49 Paul Rambone shrieked, “It belongs to the Crackers!” Leo Cristante shouted, “We’re just getting warmed up.” Billy Porter was ready to “take on the winners of the Little World Series. Then on to Cleveland.”50

This pandemonium quickly gave way to a quiet confidence and a sense of purpose, and the players calmed down and focused on the upcoming Game 7. One observer commented, “What’s the funeral about in here? I thought these guys won something.”51 Whitlow Wyatt explained this abrupt change of mood in the clubhouse: “They’re just like that. They’re not the hollering, screaming type. They can get as worked up as anybody about a ball game, but it comes out on the field. They don’t use it up until they have to. They’ve been great that way. I guess that’s the reason they’ve won.”52 The players showered, dressed, and went home. On his way out, Bob Montag confided to Atlanta sportswriter Furman Bisher: “We got it now. We got it.”53

The Crackers, so moribund in the first two contests, had rallied from a one-to-three game deficit to knot the series at three victories apiece. During the regular season, Atlanta had staged numerous comebacks to win. In late August, trailing the league-leading New Orleans Pelicans by two games, the Crackers swept the Pelicans in a four-game series to zoom into first place and to take the pennant. In both rounds of the league playoffs, the Crackers lost the opening game and then defeated their opponents. The team had one more game to play for dollars and glory. Could the Crackers come from behind one more time to win the Dixie Series and the Southern Association grand slam?

On Tuesday, September 28, a long line of people waited at the Ponce de Leon box office to buy tickets for Game 7.54 When the gates at Poncey opened at 4:50 P.M. for the 8:15 P.M. game, more than 100 people had already queued up to enter the ballpark. By 6:00 P.M., fans had taken every parking space within several blocks of Ponce de Leon Park. At 7:15 P.M. they had filled every seat in the grandstand. A large, exultant throng of 13,293 fans, the third largest of the season, jammed every nook and cranny of the place to cheer the Crackers to what they hoped would be their third straight victory.

An uproarious excitement and sense of anticipation pervaded Ponce de Leon Park. “People were sitting on soft drink crates behind the last row of grandstand seats. Others were on the rail behind them. They were practically hanging from the rafters. They overflowed into the left field section behind the fence. And there was a good crowd perched on the fence beside the railroad tracks.”55

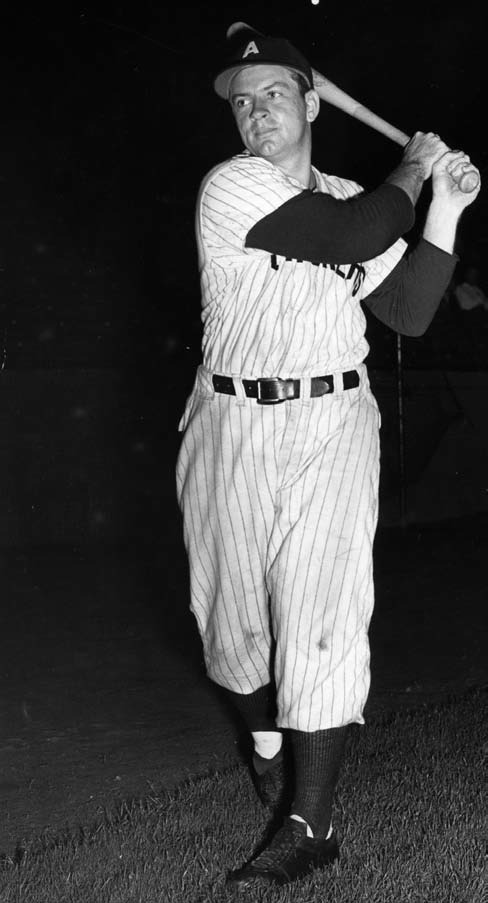

Glenn Thompson’s masterful performance in Game 5 of the 1954 Dixie Series was the best of his career. (DENNIS GOLDSTEIN COLLECTION)

In the game, Glenn Thompson, working on only two days’ rest, started on the mound for Atlanta against Houston’s Hugh Sooter, the winner of Game 4. The Buffaloes jumped off to an early lead. Believing that the left-handed batter Don Blasingame would not pull Thompson’s fastball, the Cracker outfielders swung around toward left field. Blasingame led off the game with a pop-up down the right-field line that fell in between Frank DiPrima, Frank Torre, and Chuck Tanner. The speedy Buff shortstop raced to third base for a triple, sliding in ahead of the throw.

The next hitter, Howard Phillips, lofted a long sacrifice fly to left field that scored Blasingame. Thompson retired the next two hitters, Boyer and Brown. In the second inning, Houston threatened again, putting runners on first and second base with no outs, but Thompson then struck out the next three batters. Houston had runners at first and third with one out in the third inning but again failed to score, with Thompson getting Brown and Boyd out on weak infield grounders.

Atlanta finally got on the scoreboard in the fourth inning. Chuck Tanner led off with a single. The next batter, Bob Montag, powered a triple to right field, scoring Tanner and tying the game. Pete Whisenant then hit a routine ground ball to shortstop. Montag—in what could have been a serious base-running blunder—broke for home. He got caught in a rundown. Montag, a fast runner and a big man at 185 pounds, charged the plate standing upright. He slammed into Hugh Sooter at home with the full force of his body, jarring the ball out of the Houston pitcher’s glove. Montag’s run gave the Crackers a 2–1 lead. Meanwhile, Whisenant had raced all the way to third base. After DiPrima grounded out, Jack Parks hit a sacrifice fly to deep center field, driving in Whisenant for Atlanta’s third and final run of the inning.

In the bottom of the fifth inning, Glenn Thompson led off with a single. After Vern Petty grounded into a force out, Frank Torre blasted a ground-rule double, putting Crackers on second and third base with one out and a two-run lead.

At this point in the game, the wheels of managerial strategy began to whirl. Dixie Walker replaced Sooter, a right hander, with Luis Arroyo, a lefty, to pitch to Atlanta’s two left-handed sluggers, Chuck Tanner and Bob Montag. Arroyo intentionally walked Tanner to bring up Montag with the bases loaded. The crucial moment in the game and the series had arrived. If Houston could prevent the Crackers from scoring, the momentum in the game would revert to the Buffaloes. If Montag, the Crackers’ best and most reliable power hitter, could drive in one or more runs, he could put the game out of reach.

As Montag, who had struggled all season against left-handed pitching, approached the batter’s box, Whitlow Wyatt pondered pinch-hitting for his slugger. As Wyatt explained immediately after the game: “I was thinking about it all the time, all the time he was walking to the plate. I was afraid Dixie might take out his left-hander and that would leave me with a right-handed lineup. . . . I looked over at first base and saw Chuck [Tanner] and Earl [Wooten in the first-base coach’s box.] I could tell they seemed to think it was time for a pinch hitter. . . . Then I decided that two runs right there might mean the game. . . . That’s when I sent for [Jim] Solt.”56

The fans in the stands rained a unanimous chorus of boos on Wyatt for his decision to pinch-hit the righthanded Jim Solt for Montag. In the press box, Atlanta Journal sportswriter Rex Edmondson moaned, “Whitlow has lost his mind!”57 At this point in the series, Solt was 0 for 9. But then Edmondson realized that Montag—despite his power—was vulnerable to lefthanded pitching. Edmondson also remembered that Solt, in a similar pressure-packed situation, had pinch-hit a three-run homer to win the game that gave Atlanta the honor of hosting the 1954 All-Star Game.58

Jim Solt drove Arroyo’s first pitch over the 350-foot left-field fence for a grand-slam home run. When Solt’s bat made contact with the ball, sending it soaring beyond the infield, Dixie Walker, who was standing on the dugout steps, dropped his head to his chest, shaking. The moment Solt hit it, Walker knew it was out of the park and that the game and the series had ended for the Buffaloes.59

Solt’s teammates mobbed him at home plate, and the crowd was delirious. Atlanta sportswriter Rex Edmondson had “never . . . been on the scene more unforgettable. I wasn’t in the Polo Grounds when Bobby Thomson’s blast beat the Dodgers in ’51, but I was listening and even then . . . although I was jumping with joy, it didn’t match that night at Ponce de Leon when Solt’s homer cleared the left field fence. I don’t recall how long it took Solt to cross home plate as fans and players streamed out to greet him. It was pure bedlam.”60

With a 7–1 lead, Glenn Thompson coasted the rest of the way. He got stronger as the game progressed, retiring the last 20 men he faced. The big Atlanta hurler turned in his second brilliant pitching performance in four days. He limited Houston to five hits. He struck out six and walked only two. When the Buffaloes came to bat in the top of the ninth inning, the park organist, Mrs. Johnnie Nutting, serenaded them with “I’m Heading for the Last Roundup.”

When the game ended, the jubilant Crackers hoisted a beaming Whitlow Wyatt onto their shoulders and carried him to the clubhouse. The Cracker “dressing room . . . was a bedlam. A turmoil. Like Lindbergh coming home from Paris. V-J Day.”61 Earl Mann and Charlie Hurth, the president of the Southern Association, joined the celebration, congratulating Wyatt and the players. Mann gave Thompson a bear hug and a headlock. A forlorn Dixie Walker was there too. He came to congratulate his former teammate, his former collaborator, and his friend. Wyatt told Walker, “It’s bad trying to beat your best friend, but you were trying to beat me.”62

Even after the victory and amid this joyous celebration, some of the players were amazed at what they had just accomplished. Dazed and stupefied, they sat nearly motionless, in various stages of undress. Frank DiPrima perched on a table wearing only his unbuttoned undershirt. Leo Cristante had on nothing but his undershorts. Relief pitcher Pete Modica, who had played sparingly in the series, rested on a bench, shirtless, smoking a cigarette. And Montag, one of the heroes of the game, sat on a rubbing table wearing nothing at all.

Earl Mann, who had won 10 pennants in his minor-league career, called the victory in the seventh game of the 1954 Dixie Series “the biggest thrill I’ve ever gotten out of baseball.”63 The 1954 Atlanta Crackers— their dramatic finishes and thrilling come-from-behind victories, Whitlow Wyatt’s leadership, Montag’s home runs, Thompson’s nearly flawless pitching, Donovan’s brilliant hurling and his prowess at bat, and Solt’s pinch-hit grand slam—are all part of Atlanta’s baseball legacy and the stuff of legend and lore. The 1954 Atlanta Crackers won the Southern Association grand slam in storybook fashion. Their victory was, as Rex Edmondson put it, “The Miracle of Ponce de Leon.”64

KEN FENSTER is professor of history at Georgia Perimeter College, Clarkston Campus. His baseball writing has appeared in “Nine”, “The New Georgia Encyclopedia”, “The African American National Biography”, and “The Baseball Research Journal”. He currently is researching the life of Atlanta Cracker executive Earl Mann.

FACTS AND FIGURES ON THE 1954 DIXIE SERIES

|

Game 1 – September 21 in Atlanta |

|

Game 4 – September 24 in Houston |

|

Game 7 – September 28 in Atlanta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Houston – 10 |

|

Atlanta – 2 |

|

Houston – 1 |

|

Atlanta – 4 |

|

Houston – 5 |

|

Atlanta – 7 |

|

WP – Luis Arroyo |

|

WP – Hugh Sooter |

|

WP – Glenn Thompson |

|

LP – Glenn Thompson |

|

LP – Don McMahon |

|

LP – Hugh Sooter |

|

HR – Fred McAlister, Houston |

|

HR – Bob Boyd, Houston |

|

HR – Jim Solt, Atlanta |

|

Pete Whisenant, Atlanta |

|

Attendance – 9,115 |

|

Attendance – 13,293 |

|

Attendance – 11,495 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Game 2 – September 22 in Atlanta |

|

Game 5 – September 25 in Houston |

|

Totals |

|

Houston – 7 |

|

Atlanta – 1 |

|

Houston: 3-4 |

|

Atlanta – 2 |

|

Houston – 0 |

|

Atlanta: 4-3 |

|

WP – Willard Schmidt |

|

WP – Glenn Thompson |

|

Attendance: 73,628 |

|

LP – Leo Cristante |

|

LP – Luis Arroyo |

|

(42,065 in Atlanta) |

|

HR – Frank DiPrima, Atlanta |

|

HR – None |

|

(31,563 in Houston) |

|

Attendance – 6,830 |

|

Attendance – 10,876 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Game 3 – September 23 in Houston |

|

Game 6 – September 27 in Atlanta |

|

|

|

Atlanta – 7 |

|

Houston – 2 |

|

|

|

Houston – 4 |

|

Atlanta – 6 |

|

|

|

WP – Dick Donovan |

|

WP – Dick Donovan |

|

|

|

LP – James Atchley |

|

LP – Willard Schmidt |

|

|

|

HR – Bob Montag, Atlanta |

|

HR – None |

|

|

|

Attendance – 11,572 |

|

Attendance – 10,447 |

|

|

Gate Receipts

$130,367.05 divided as follows:

$20,576.40 for the Atlanta players

$13,723.99 for the Houston players

$34,996.64 for each club

$13,036.69 for each league65

Notes

1 1. The principal sources on which this article is based are the two daily newspapers in Atlanta, the Atlanta Constitution and the Atlanta Journal; the two daily newspapers in Houston, the Houston Chronicle and the Houston Post; 42 interviews that I conducted with players from the 1954 Atlanta Crackers; Atlanta sportswriters, fans, and others in 1999–2000; and personal correspondence with former Atlanta sportswriters Bob Christian and Rex Edmondson. The two leagues played the first Dixie Series in 1920, when the pennant-winning teams challenged each other for bragging rights as the best baseball outfit in the South. The following year, the two leagues formally arranged a best-of-seven postseason championship series, establishing the Dixie Series as an official playoff. The games in these first two years attracted large crowds, immediately making the Dixie Series a financial success, establishing it as the most popular and premier baseball event in the South, and guaranteeing its continuance. Except for 1943 through 1945, when the Texas League suspended operations, the series continued through 1958. For a general discussion of the Dixie Series and its importance, see Charles Hurth, Baseball Records: The Southern Association, 1901–1957 (New Orleans: The Southern Association, 1957), 132–36; Robert Obojski, Bush League: A History of Minor-League Baseball (New York: MacMillan, 1975), 245–47; Bill O’Neal, The Southern League: Baseball in Dixie, 1885–1994 (Austin, Tex.: Eakin Press, 1994), 42–43; Marshall Wright, The Southern Association in Baseball, 1885–1961 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2002), 203–4; Tom Kayser and David King, Baseball in the Lone Star State: The Texas League’s Greatest Hits (San Antonio, Tex.: Trinity University Press, 2005), 55–59.

2 Between 1938, when the Southern Association played its first All-Star Game, and 1954, four other teams had come close to capturing the grand slam. In 1940, the Nashville Vols lost the All-Star Game 6–1 and then took the pennant, the playoffs, and the Dixie. In 1943, the Vols won the first three legs of the grand slam but did not have the opportunity to play in the Dixie Series because the Texas League suspended operations. The 1946 Crackers won the All-Star Game, the pennant, and the playoffs but lost to Dallas in the Dixie. The 1949 Vols lost the All-Star Game 18–6 and then won the pennant, the playoffs, and the Dixie. Principal source: Hurth, Baseball Records, 13–14, 126–36.

3 These team statistics and all the statistics in this and the following paragraphs came from the Sporting News Guide and Record Book (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1954), 204–12 (Texas League), 196–203 (Southern Association).

4 For a synopsis of Brown’s career, see James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994), 127–29. See also John Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It (Westport, Conn.: Meckler Books, 1989), 107–18.

5 Houston Post, 19 September 1954.

6 On the importance of the outfielders to Atlanta’s offense, see, for example, the photo of Montag, Whisenant, and Tanner in the Atlanta Constitution (10 September 1954). The caption reads: “They accounted for 300 Cracker runs batted in this year.” Combined, the three outfielders had 39 percent of the team’s RBI, scored 34 percent of the team’s runs, made 39 percent of the team’s extra-base hits, and hit 48 percent of the team’s home runs. These statistics are all the more impressive when one considers that Whisenant did not join Atlanta until May 11, missing the first month of the season, when he was with Triple A Toledo.

7 In many seasons, Montag’s and Tanner’s numbers would have led the Southern Association, but not in 1954, when Nashville’s left-handed slugger Bob Lennon took advantage of Sulpher Dell’s short 262-foot rightfield fence to win the triple crown (.345, 64, 161) and lead the league in total bases with 447, hits with 210, and slugging percentage at .733.

8 Hurth, Baseball Records, 91.

9 The Atlanta Journal first mentioned Torre’s errorless-games streak in its May 7 issue, when Torre had played in 25 games and handled 254 chances. The Journal referred to the streak again in its May 20 issue, and in its May 23 issue declared: “Frank Torre may be the slickest fielding first baseman in Southern history. No one can produce any statistical evidence to the contrary, for the Cracker whiz is operating at an unbreakable clip. Perfect is par for him thus far.” For Danforth’s evaluation of Torre, see the Atlanta Journal (28 May 1954). The Sporting News (9 June 1954) featured Torre’s errorless streak in its roundup of the Southern Association.

10 On Donovan mastering his temper and the slider, see Dick Donovan, as told to Al Silverman, “I Almost Gave Up,” Sport 21 (February 1956): 46, 75; interview with Chuck Tanner, 8 June 1999; Rex Edmonson to the author, 21 April 1999; Atlanta Journal, 10 March 1960; Charlie Roberts Papers, Atlanta History Center, MS 552, box 11, folder 2; Atlanta Journal, undated clipping, Southern Bases Collection, Atlanta History Center, MS 735, box 2, folder 7, clippings (11 June 1955, 4 September 1957, 5 April 1958), Donovan File, National Baseball Library; Atlanta Constitution (31 July 1957) and clippings (March 1955, 6 July 1955), Donovan file, Sporting News Archives; David Condon, “Tricky Dick’s $30,000 Pitch,” Chicago Sunday Tribune Magazine, 14 May 1958, 14; Sandy Grady, “Donovan’s Up,” Sport 27 (November 1962): 41, 74; Howard Roberts, “How Donovan Finally Found Success in One Easy Lesson,” Baseball Digest 14 (September 1955): 46; Bob Vanderberg, Sox from Lane and Fain to Zisk and Fisk (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1982), 172–73.

11 Atlanta Constitution, 24, 27 September 1954; Atlanta Journal, 27 September 1954.

12 Sporting News, 15 September 1954.

13 Hurth, Baseball Records, 96.

14 The only catcher or catching platoon in the league that had more offensive success than the Solt-Parks tandem was Birmingham’s Lou Berberet, who hit 18 home runs, scored 93 runs, drove in 118 runs, and batted .317.

15 Hurth, Baseball Records, 87. Donovan hit two more home runs in the playoffs, including a 450-foot blast in New Orleans on September 19. The day after Donovan hit this mammoth home run, the Atlanta Constitution published a photo of the pitcher holding his bats. As a hitter, Donovan apparently inspired fear in some opposing pitchers. In the third playoff game against Memphis, Atlanta, with a 2–0 lead, had runners on second and third with no outs. Memphis pitched to the number-eight hitter, Paul Rambone, who had 19 home runs for the year. He struck out. Memphis then intentionally walked Donovan to pitch to leadoff batter Billy Porter!

16 The Atlanta Journal (13 July 1954) described Wooten as the “wittiest” man on the team, who could earn a living as a gag writer. The Atlanta Journal (20 August 1954) wrote as follows: “Dick Donovan and Bill George, along with Junior Wooten, Paul Rambone, and Pete Whisenant, are comparable to a picnic with Martin and Lewis, Abbott and Costello, and Red Skelton.” When I interviewed Wooten, he denied that he was the team’s leading practical joker, prankster, or comedian. Interview with Earl Wooten, 10 April 1999.

17 Wooten went to spring training knowing that he would not be a regular. Interview with Earl Wooten, 10 April 1999.

18 When Wooten went in to play center field, Whisenant, the regular center fielder, shifted to left field, and Montag, the regular left fielder, came out.

19 The idea for this and the next three paragraphs comes from the Atlanta Journal (7 February 1962), Charlie Roberts Papers, Atlanta History Center, MS 552, box 13, folder 5.

20 On Peeples and the effort to integrate the league, see Kenneth R. Fenster, “Earl Mann, Nat Peeples, and the Failed Attempt of Integration in the Southern Association,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 12 (spring 2004): 73–101.

21 Atlanta Journal, 19 September 1954; Atlanta Constitution, 21 September 1954. After he retired from baseball, Brown made his home in Houston, where he remained extremely popular and a fan favorite until he died. See Riley, Biographical Encyclopedia, 128–129.

22 Blacks and whites had competed against each other at Ponce de Leon Park every year since 1949, but only in exhibition games. See Fenster, “Earl Mann, Nat Peeples,” 85–87.

23 After the 1952 season, Walker accepted a coaching position with the St. Louis Cardinals. Earl Mann hired Gene Mauch as Cracker manager for 1953, giving Mauch his first managerial job. At their regular meeting in November 1952, Southern Association officials passed a rule prohibiting coaches, forcing Wyatt to retire to his farm in Buchanan, Georgia, for the 1953 season.

24 Houston Post, 7 September 1954.

25 Atlanta Journal, 19 September 1954. See also Atlanta Constitution, 20, 21 September 1954; Atlanta Journal, 20 September 1954.

26 Atlanta Journal, 20 September 1954.

27 Atlanta Constitution, 21 September 1954.

28 Atlanta Constitution, 22 September 1954.

29 This attendance was the sixth largest of the season to date.

30 Atlanta Constitution, 22, 29 September 1954; Atlanta Daily World, 23 September 1954; Sporting News, 6 October 1954. See also Furman Bisher, “What About the Negro Athlete in the South?” Sport 21, May 1956: 88. In this article, Bisher writes, “Atlanta’s Negro population nearly created a crisis when it turned on the Crackers to cheer for [Houston’s] Negro stars. Passions arose on an occasion or two, but subsided abruptly and the series came off without incident.”

31 Houston Post, 23 September 1954; Houston Chronicle, 23 September 1954.

32 Houston Post,23 September 1954.

33 Ibid. See also Atlanta Journal, 23 September 1954.

34 Atlanta Journal, 22 September 1954.

35 Atlanta Journal, 23 September 1954.

36 Atlanta Journal, 29 September 1954.

37 Atlanta Journal, 22 September 1954; Houston Post, 27 September 1954.

38 Interview with Earl Wooten, 10 April 1999.

39 Houston Chronicle , 24 September 1954; Atlanta Constitution, 24 September 1954; Atlanta Journal, 24 September 1954.

40 Atlanta Constitution, 25 September 1954.

41 In addition to the game write-up in the Atlanta Journal (26 September 1954), I have relied on the description of this hit found in Rich Marazzi, “The Tumultuous Life of Pete Whisenant,” Sports Collectors Digest (30 August 1996): 90.

42 Atlanta Journal , 26 September 1954; Earl Mann, “How Baseball Can Live with TV,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine , 6 March 1955: 9. See also interview with Earl Mann by Loran Smith, undated, Georgia Sports Hall of Fame archives. This interview is undated, but internal evidence suggests early 1980s. Glenn Thompson called this game the best performance of his career. Interview with Glenn Thompson, 17 June 2000.

43 On Donovan’s personality off the mound, see Rex Edmondson to the author, 21 April 1999; Grady, “Donovan’s Up,” 39; Dick Gordon, “The Truth About Donovan,” Baseball Digest 21 (July 1962): 23; “Baseball: Split Personality,” Newsweek 59 (June 1962): 87; Vanderberg, Sox, 173–74; clipping (August 1961), Donovan File, Sporting News Archives.

44 Photo of Donovan and George in Atlanta Constitution, 27 September 1954.

45 Marazzi, “Tumultuous,” 90; Atlanta Constitution, 28 September 1954; Atlanta Journal, 28 September 1954.

46 Atlanta Journal, 28 September 1954.

47 According to Bill James and Rob Neyer, Donovan had a “Hall of Fame slider in the 1950s” and had the ninth-best slider in baseball history. See The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), 38.

48 After a bolt of lightning struck the chimney of the Kimble House Hotel in downtown Atlanta, Petty, who was taking a walk with his uncle, was struck in the leg by a falling brick. See Atlanta Constitution, 20 August 1954; Atlanta Journal, 20 August 1954.

49 Atlanta Journal, 28 September 1954.

50 Atlanta Constitution, 29 September 1954.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

53 Atlanta Constitution, 28 September 1954.

54 See the photograph of this line in the (Atlanta Journal, 28 September 1954).

55 Atlanta Journal, 29 September 1954.

56 Whitlow Wyatt in the Atlanta Constitution and Atlanta Journal (29 September 1954). In the quotation cited in the text, I have combined Wyatt’s statements as published in the two newspapers.

57 Rex Edmondson to the author, 21 April 1999.

58 On Solt’s pinch-hit home run that gave Atlanta the All-Star Game, see Kenneth R. Fenster, “It’s Not Fiction: The Race to Host the 1954 Southern Association All-Star Game,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Association Conference, Birmingham, Ala., 7 March 2009.

59 Rex Edmondson to the author, 21 April 1999.

60 Ibid.

61 Atlanta Constitution , 29 September 1954.

62 Ibid.

63 Atlanta Constitution, 30 September 1954. See also Earl Mann in The Sporting News, 6 October 1954) where he is quoted as saying: “It’s the greatest thrill I’ve ever gotten out of baseball.”

64 Rex Edmondson to the author, 21 April 1999.

65 Atlanta Journal, 30 September 1954.