The Astrofuturism of Baseball

This article was written by Harrie Kevill-Davies

This article was published in The National Pastime: The Future According to Baseball (2021)

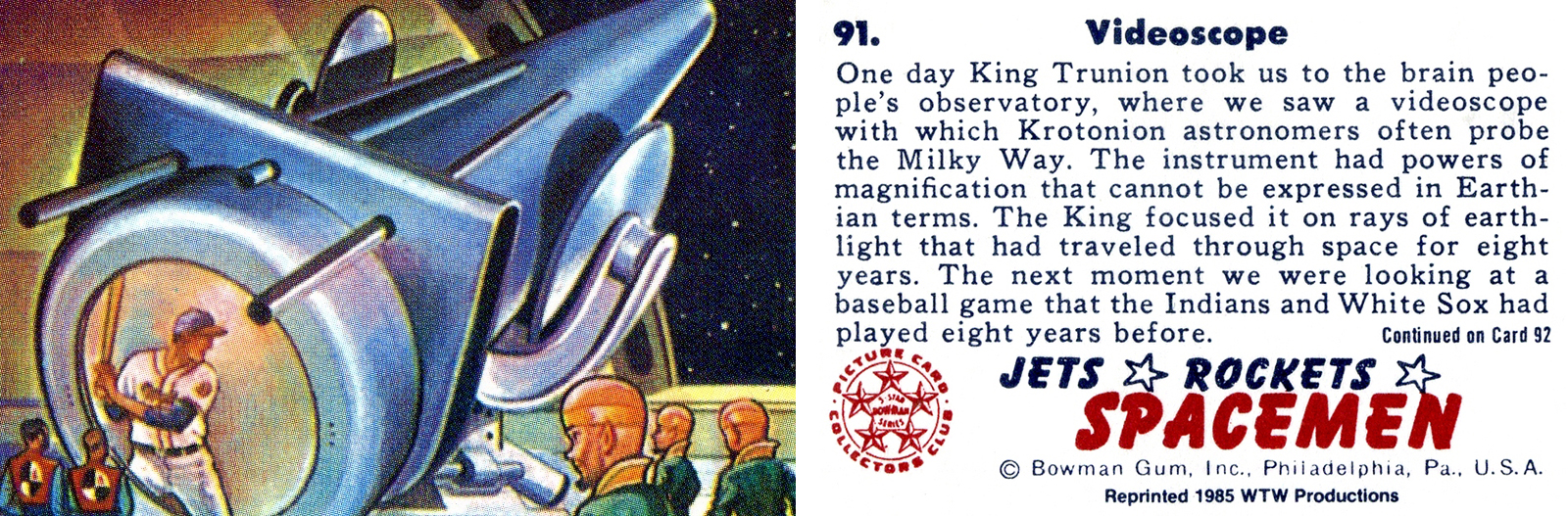

In one of the 1951 Bowman trading card sets, Jets, Rockets, Spacemen, visitors from Earth watch a baseball game beamed from Cleveland years earlier via alien technology. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

In October 2019, three American astronauts aboard the International Space Station played baseball to mark the final game of the World Series, in which the Houston Astros were participating. In a video shared on Twitter, Jessica Meir pitched a 17,500 mile-per-hour fastball, which Drew Morgan hit with a makeshift bat, a flashlight.1 Christina Koch, in the position of catcher, remarked that “as we prepare to send the first woman and the next man to the surface of the moon, we say we are proud to be from Houston, home of the astronaut corps.”2 Despite the novelty of this event, we can trace the history of baseball in space right back to the early Cold War. Even if space travel is not yet living up to the visions of science fiction, baseball being played on the ISS suggests life is imitating art. In this article, I trace the threads of connection between baseball and space from the mid-twentieth century to the present. I suggest that as we look to the future, if we are to have a truly international and collaborative presence in space, we must consider how—or whether—we can disentangle it from iconic signifiers of American culture such as baseball.

In 1951, the Bowman Gum Company of Philadelphia released a set of non-sports trading cards named Jets, Rockets, Spacemen. The set, released seven years prior to the launch of NASA, presented its readers with a vision of what space travel might look like in the near future. The card set features a young cadet blasting off into space for the first time from a base in Manhattan. Our hero works for the United States in concert with the United Nations and the so-called Solar League in the defense of universal peace, hinting at the spirit of the Truman Doctrine. Invoking the concept of light years, card number 91 of the set, “Videoscope,” shows astronauts who have journeyed across galaxies watching “a baseball game that the Indians and White Sox had played eight years before.”3

In “Videoscope” it is assumed that, even in outer space, astronauts will want to watch baseball. This implies future astronauts are from the United States, where baseball reigned as the national pastime at the time of the card set’s issue.4 In the context of contemporary non-sports cards, many of which taught American history, baseball takes its place within visions of America’s future as well as within commemorations of America’s past. Even in entirely non-sports sets, baseball makes several appearances, and cards featuring players proved particularly popular both at the time and among later collectors. By including baseball in cards that both look back at America’s past and forward to its future, it is assumed not only that baseball will be endlessly present, but also that it is consequential to the development of American history and identity. The fact that Bowman’s primary business was baseball cards may explain this inclusion; the firm wished to promote its most lucrative product. However, even in arenas other than trading card markets, the idea that baseball has a role to play in the maintenance of global democracy was not uncommon in this period. In his famous book, Coca-Colonization and the Cold War, historian Reinhold Wagnleitner cites an American general in Berlin in 1945 as saying, “We only have to teach German kids how to play baseball—then they’ll understand the meaning of democracy.”5

The idea that control of space might be critical to the global (or even galactic) spread of democracy was prevalent in this period, with space technology being developed primarily to preempt undeclared nuclear strikes. Although the early development of the space program was driven by the concept of the “free skies,” according to which no nation could lay claim to portions of space, it was generally assumed that American technological supremacy would prevail, and that such policy could contain perceived nefarious plans for space on the part of the USSR6. However, during this earlier period of space development, scientists and science fiction writers known as astrofuturists used popular science and science fiction to promote the public interest in manned space travel, partly in order to increase support for the nascent space program.7 These astrofuturist evangelists included both science fiction writers and actual scientists, including some of the rocket scientists who had come to the United States from Germany after World War II to develop rocketry for missiles and space travel. The most famous of these, Wernher von Braun, was a staunch astrofuturist, whose plans for space travel were recorded in serial format in Collier’s Magazine in 1952 and 1953, illustrated according to von Braun’s plans by Chesley Bonestell. Von Braun painted his vision of the space future in decidedly suburban terms, with an emphasis on “professional activity and middle-class luxuries,” placing himself “within a context of industrial activity and suburban domesticity, thereby offering his readers a fair example of how astrofuturism could make sense during the 1950s.”8 In essence, space was shown as a natural extension to postwar suburban affluence—an affluence that had itself been driven by the scientific and technological developments that had brought about victory in WWII, the nuclear program, and the idea of sending men to space.9 Although space was indeed the final frontier, in the eyes of astrofuturists, the point of getting there was to replicate the prosperous mode of living of the postwar United States.

In this context, we can see how baseball, as a critical component of the American Way of Life, might fit neatly into visions of intergalactic travel. Today it is striking how suburban many of the places visited by the hero of Jets, Rockets, Spacemen appear. Although the space settlements are referred to as cities, they follow regular layouts like tract housing (and in the early days of the postwar suburbs, tract housing plans were also “advertised and perceived” as cities.)10 Space stations are connected by curving highways and railways, resembling those advertised by Bohn Aluminum and Brass Corporation, Vanadium Corporation of America, and contemporary engineering firms. Space buildings and ships alike have picture windows, providing wide vistas over the galaxy, while ships also have “telescreens,” just as suburban homes had televisions, their “windows on the world.”11 The design of ships closely resembles that of contemporary cars and futuristic imaginations of other modes of transport in contemporary advertising, as well as domestic appliances. They feature the “bulbous streamlined forms” common to the period, and as such would have been familiar to targeted boy readers not only as staples of science fiction but also as everyday items.12 Therefore it is not surprising that in the Videoscope card, astronauts use a machine that bears this kind of design to watch that most American of sports, baseball.

This collapsing of outer space with familiar Americana can also be seen clearly across depictions of baseball in space. Another case study is the popular Hanna-Barbera animated show, The Jetsons. This cartoon gave us a glimpse of how baseball might be played in the future. In the 1985 episode “Team Spirit,” the consummate organization man George Jetson appears as the star pitcher for his firm, Spacely Sprockets, in a game of Spaceball against its rival, Cogswell Cogs.13 Both companies rely on robots to play the game, with Cogswell warming up against a robot pitcher, George Jetson attended by a remote-controlled robot valet, and other robots participating as players. This vision of baseball, coming at the height of the Reagan presidency, and in the wake of the Strategic Defense Initiative (also known as “Star Wars”), tapped into contemporary ideas about the possible future of the United States in relation to space exploration.

During the 1980s, despite a number of catastrophic, tragic setbacks, NASA was invested in building reusable space shuttles that could run service missions to space telescopes, and could build and populate an international space station in orbit. In this sense, the 1980s space program was heightening the mundanity of space travel, converting it from a monumental effort to achieve a single, defined mission, to a routine transportation and habitation system. The fact that The Jetsons was revived during this period fits with this ethos-space travel was a hot topic, but was presented in terms of setting up daily life and routine there, with All-American home comforts, including baseball. The Jetsons showed us what it might be like to live, work, and play baseball in other galaxies, fueling the expansion of the American Dream into new frontiers.

The initial run of The Jetsons was launched in 1962, during a time when space fervor was all the rage, just a year after President John F. Kennedy’s “Moon Shot” speech, in which he spoke to a Joint Session of Congress about the nation’s aspirations for the mastery of space.14 The first episode aired a mere 11 days following Kennedy’s well-known speech at Rice University in which he said, “I regard the decision last year to shift our efforts in space from low to high gear as among the most important decisions that will be made during my incumbency in the office of the Presidency.”15 In that speech, Kennedy framed manned space travel as a fait accompli, the natural conclusion to centuries of scientific research. He also famously likened space exploration to earlier American frontiers, presenting it as a place to be conquered, tamed, and inhabited. As Kennedy primed both Congress and the population for the excitement of space travel, astrofuturists had been doing just that for a decade or more, using popular science and science fiction, partly in order to increase support for the space program among the public. As De Witt Douglas Kilgore points out, astrofuturist boosters depicted space as “not an impossible Arcadia but as a feasible movement into new territories that conformed to established and predictable laws,” and showed visions of space composed of “familiar tools and mundane, lived spaces.”16 If we take up this claim, Jets, Rockets, Spacemen and The Jetsons can be seen as astrofuturist pieces, in that they both demonstrate life in space as a normal extension of American family life, with all the same routines and relationships one would expect in an archetypal suburban American town. Both artifacts assume that manned space travel will occur, result in an expansion of the American Dream, and look like American life-complete with baseball.

These examples show that for all the talk of collaborationist ideals, the inhabitation of space has been seen as an American project that would spread American values across the world and even across galaxies, and the presence of baseball in space marks American cultural dominance during the Cold War. However, by the late 1980s, baseball faced a potential demise; in a 1988 episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation set in the twenty-fourth century, we learn that the popularity of baseball spread across the world, then waned. An episode of Star Trek Deep Space 9 confirms that the last ever World Series was played in 2042.

Given the highly collaborative and internationalist (and even intergalactic) vision of space put forward by the Star Trek franchise, the diminishing presence of such a strong signifier of American cultural dominance makes sense. That said, baseball does appear in several episodes, most notably the Deep Space 9 episode “Take Me Out to the Holosuite” in which the crew of the space station are challenged to a game of baseball by visiting Vulcans. Although baseball is supposedly no longer popular by the twenty-fourth century, and the DS9 space station is inhabited by humans from other nations than America, and by other species, the game still appears as a manifestation of American culture, once again showing us that space is an American venture. The space station Commander, Sisko, is portrayed as an American who nostalgically enjoys playing baseball with his son Jake. In the show, baseball is described as “a contest of courage, teamwork, and sacrifice” and one that requires “faith” and “heart,” all of which could reasonably be described as values associated with the American way of life. Although most of the crew have never played baseball before, and have to read the rules to understand even the most basic tenets of the game, the space station holosuite is able to recreate a baseball stadium with bleachers and a working scoreboard, while all the players wear standard twentieth-century baseball uniforms. Therefore, even in a vision of space that is highly progressive in its approach to inclusivity and diversity, baseball remains a signifier of an American culture to which all residents of the space station have access. Even in a distant space station, the hegemonic sway of American culture is seen as privileged.

Likewise, when we see astronauts aboard the International Space Station playing baseball in space in 2019, we are reminded that even in this collaborationist venture, American cultural norms are highlighted and broadcast around the world. The video provided a fun promotion for the World Series, and an entertaining view for viewers on Earth of life aboard the ISS. Moreover, it gave us a glimpse of how both Major League Baseball and NASA have made strides toward equity and diversity in the twenty-first century. MLB has increased its outreach to young female players and female fans, while NASA is sending increasing numbers of women to space. However, even amid twenty-first century pushes toward equity, when we put men and women into orbit, the ways in which we imagine it happening have often been foreshadowed by science fiction. Even on the final frontier, we aim to replicate the comforting signifiers of American culture that proliferated in the postwar period. As we look forward to 2040, and as SpaceX works toward Elon Musk’s goal of colonizing Mars, the idea of playing baseball in space becomes less far-fetched. But the fact that we have this idea at all has its roots in Cold War American expansionism and science fictional visions. Despite the noble twenty-first century aims of inclusivity, and the inherent collaborationism of projects like the ISS, it has become difficult to envision the future of space as anything other than dominated by the United States, and one way in which this is signified is the existence of baseball in space.

HARRIE KEVILL-DAVIES is a doctoral candidate in Rhetoric and Public Culture at Northwestern University. Her dissertation focuses on early Cold War non-sports trading cards, especially how they depict history, science, and war. She is also interested in how non-sports cards overlap with sports, and always enjoys seeing baseball in non-sports cards. Although originally from London, she has lived in Chicago for almost 10 years, and has enjoyed the return to post-pandemic Wrigley Field to root for the Cubbies!

Notes

1. Jennifer Leman, “Watch NASA Astronauts Throw a 17,500 mph Fastball” in Popular Mechanics, October 31, 2019. https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/satellites/a29655302/nasa-astronaut-fastball (accessed March 24, 2021).

2. Tweet by @MLBonFOX, October 25, 2019, including video from the International Space Station and the text “Ever wonder what it would be like playing baseball in space? Take a look at our friends from @Space_Station enjoying the game we love!” https://twitter.com/MLB0NF0X/status/1187914643991220224?s=20.

3. The specifics of the game are not mentioned, but the Indians played the White Sox 22 times in the 1943 season, including several (6) double headers.

4. The astronauts could plausibly be Korean, given that baseball was popular there from the nineteenth century, but we are reminded that baseball was introduced to Korea by missionaries, placing it firmly within the notion of baseball as part of a mission to civilize the racial or cultural other.

5. Reinhold Wagnleitner, Coca-colonization and the Cold War: the cultural mission of the United States in Austria after the Second World War, E Book ed. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 1. https://search.library.northwestern.edu/discovery/fulldisplay/alma9917669754202441/01NWU_INST:NULVNEW.

6. See R. Cargill Hall, “Origins of U.S. Space Policy: Eisenhower, Open Skies, and Freedom of Space,” in Exploring the Unknown: Selected Documents in the History of the U.S. Civil Space Program, ed. John M. Logsdon et al., The NASA History Series (Washington D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration: NASA History Office, 1995). and Roger D. Launius, “Space Technology and the Rise of the US Surveillance State,” in The Surveillance Imperative: Geosciences During the Cold War and Beyond, ed. Simone Turchetti and Peder Roberts (New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014).

7. Several texts discuss early astrofuturism among science fiction writers, like Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke, as well as scientists associated with the early space program, notably rocketry scientist Wernher von Braun. These texts include McCurdy, Howard E., Space and the American Imagination. 2nd Ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, McCurdy, Howard E., and Roger D. Launius. Imagining Space: Achievements, Predictions, Possibilities, 1950-2050. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books LLC, 2001., Kilgore, Douglas De Witt, “Astrofuturism: Science, Race, and Visions of Utopia in Space,” University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003, and Geppert, Alexander C.T. (ed), Imagining Outer Space— European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

8. “Astrofuturism: Science, Race, and Visions of Utopia in Space,” University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003, https://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/13909.html.

9. There is a wealth of writing on how technological advances of the wartime period both powered and infiltrated design, appliances, and daily life in the postwar suburbs. For more, see Whitfield, S.J. 1991. The Culture of the Cold War, Baltimore, MD, The Johns Hopkins University Press., Colomina, B., Brennan, A. & Kim, J. (eds.) 2004. Cold War Hothouses: Inventing Postwar Culture, from Cockpit to Playboy, New York: Princeton Architectural Press and Cohen, L. 2003. A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America, New York, Vintage Books.

10. Barbara Miller Lane, Houses for a New World: Builders and Buyers in American Suburbs, 1945-1965 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015), 13.

11. For more on how television operated as a window on the world, see Lynn Spigel, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013/11/26/, 2013). http://www.amazon.com/Make-Room-TV-Television-Postwar-ebook/dp/B00ICQO8AM/ref=mt_kindle?_encoding=UTF8&me=.

12. Laura Scott Holliday, “Kitchen Technologies: Promises and Alibis, 1944-1966,” Camera Obscura 47, no. 16:2:87.

13. The Jetsons, season 2, episode 31, “Team Spirit,” directed by Art Davis, Oscar Dufau, Carl Urbano, Rudy Zamora, Alan Zaslove, written by Gary Warne, aired November 11, 1985, in syndication. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1287171.

14. John F. Kennedy, The Decision to Go to the Moon, Speech before Joint Session of Congress, delivered May 25, 1961, National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Office, https://history.nasa.gov/moondec.html (accessed March 22, 2021).

15. John F. Kennedy, Address at Rice University on the Nation’s Space Effort, delivered September 12, 1962. https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/historic-speeches/address-at-rice-university-on-the-nations-space-effort (accessed March 22, 2021).

16. Kilgore, “Astrofuturism: Science, Race, and Visions of Utopia in Space,” 3.