The Atlanta Black Crackers

This article was written by Leslie Heaphy

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

Atlanta’s baseball history is dominated by names such as Hank Aaron, John Smoltz, Greg Maddux, Dale Murphy, and Chipper Jones. The Braves also dominated their division in the 1990s, but that is only a small part of Atlanta’s long and storied baseball history. Anyone can look up the history of the Braves and their players to learn more. A lesser-known part of the diamond tale goes back to the days when America was segregated. Atlanta had a significant black population who had to entertain themselves separately. In part due to the pervasive Jim Crow laws, black baseball in Atlanta flourished on the sandlots and local diamonds. Only one local team really made it to the big time, the Atlanta Black Crackers, who played in the city off and on from 1919 to 1949. The Black Crackers took their name from the white Atlanta Crackers squad, hoping to benefit from their popularity and name recognition. This part of the story of Atlanta’s baseball needs to be taken out of the shadows and added to the city’s story.

Ponce De Leon Park, home of the Atlanta Crackers, became home to another team shortly after the 1919 season began: the Atlanta Cubs, the predecessor to the Black Crackers. That team consisted of Atlanta players and college athletes brought together by a group of local businessmen.[fn]Atlanta Constitution, 14 September 1918.[/fn]

Atlanta Crackers general manager Frank Reynolds realized that he could lease the ballpark to the black ballclub when the Crackers went on the road and thereby increase the Crackers’ profits. The Cubs were a hard-hitting team that got off to an immediately strong start against a variety of opponents. While playing a series in Birmingham, the Cubs so impressed area fans that they came back to Atlanta with a new name, the Atlanta Black Crackers.[fn]Allen E. Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, MA thesis, Auburn University, 1975, 14–15.[/fn] By the end of the summer season, the Black Crackers had played all over the South and had beaten teams from New Orleans to Florida and many places in between.

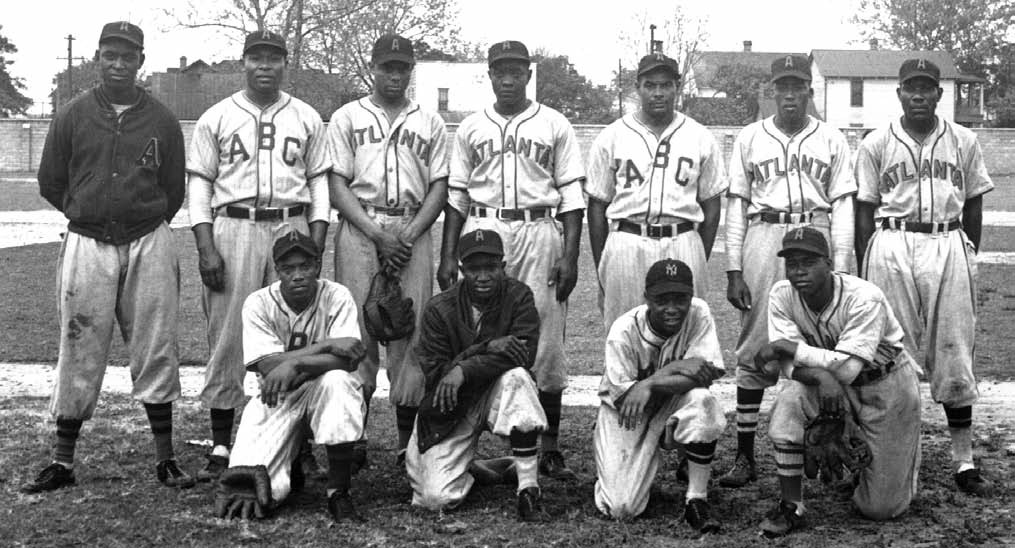

The Atlanta Black Crackers posing for a team photo before a game. (COURTESY OF THE NEGRO LEAGUES BASEBALL MUSEUM)

Insurance man W. J. “Bill” Shaw took over the Black Crackers in 1920, for their second season. Shaw moved to Atlanta from Brunswick, Georgia, and added to his insurance work a social club that held dances in the rooftop garden of the Odd Fellows Building and Auditorium on Auburn Avenue. This avenue was the heart and soul of the African American community in Atlanta. “More financial institutions, professionals, educators, entertainers and politicians were on this one mile of street than any other African American street in the South.”[fn]“Sweet Auburn Avenue: Triumph of the Spirit,” http://sweetauburn.us/ intro.htm; Gary Pomerantz, Where Peach Tree Meets Sweet Auburn (New York: Scribner, 1996); Cynthia Griggs Fleming, Soon We Will Not Cry (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2000).[/fn] The social club’s profits helped finance the ballclub, and a number of the players played in the club’s orchestra. Shaw helped the Crackers line up games to play at Morris Brown University Field and at Ponce de Leon Park. Many of the early ball players joined the club from the local colleges, including Morris Brown and Morehouse. He ran the team on a shoestring budget with twelve players and handme-down equipment and uniforms from the white Crackers team.[fn]Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 17; Clifford M. Kuhn et al., Living Atlanta: An Oral History of the City (Atlanta: University of Georgia Press, 2005), 266–67.[/fn]

When the Black Crackers played at Ponce De Leon Park, they attracted good crowds, including a sizable number of white fans. When the Black Crackers played, fans could sit anywhere in the park, but when the white Crackers played, the seating was segregated. Black fans sat in the bleachers in left field, an area they called Buzzard’s Roost, according to former player Gabby Kemp.[fn]“Black Crackers Get Second Straight Win Over Black Barons,” Atlanta Constitution, 8 July 1921, 10; Kuhn, Living Atlanta, 272.[/fn] Even with good fan support the Black Crackers struggled, because they could not afford to travel north to play the major Negro League teams, and those teams did not regularly include a swing through the South in their season schedule. As a result, the Black Crackers played all but one season outside the major Negro Leagues and spent much of their playing time traveling to wherever a paying gig could be found. Atlanta sportswriter Ric Roberts described the importance of the Black Crackers to the local community, saying: “Baseball was an outlet. To sit where the whites sat—it was a moment of escape. . . . Blacks have always loved baseball. . . . And it gave them a chance to look at their heroes.”[fn]Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 10.[/fn]

When the Negro Southern League (NSL) formed in 1920, the Black Crackers became members, paying the $200 franchise fee and hoping for a successful first season. Unfortunately the club struggled, and by August their record only stood at 39–37. While not a success on the field, the Black Crackers proved that a team could survive in Atlanta. They returned for another year, opening the 1921 season in early April with a win against the Federal Prison Indians. They also ended their season by defeating the Federal Prison Indians[fn]Atlanta Constitution, 4 April 1921.[/fn] again, 3–2. Big Preacher Davis struck out sixteen for the winners. Although they spent much of the season on the road, where they made better money due to larger crowds and not having to pay to lease ballparks, their financial struggles caused the team to dissolve before the end of the season.

The Black Crackers did not return to league play until 1925, because the college players lost their eligibility if they played for money. Thus the club could not find enough good players to field a team, and without a strong team they could not afford the rental fees for a park.[fn]“Wildcats and Black Crackers Cross Bats,” Savannah Tribune, 11 and 18 June 1921; “Black Crackers Defeat Indians,” Atlanta Constitution, 3 October 1920; 3B; Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 20–21.[/fn]

New money and organization came to the team in 1925 in the forms of businessmen H. J. Peek and George Strickland. The team still spent a lot more time on the road because Atlanta’s blue laws meant that Sunday baseball had to be played in other towns. Due to the Black Crackers’ long absences from home, little about them can be found in the papers, and fans found it difficult to follow the team’s progress. The weekly Atlanta Daily World did not start coverage until 1928 and did not become a daily until 1932. The Atlanta Constitution gave only sporadic coverage.

The club disappeared again before the end of the 1925 season. Peek brought the club back in 1926 with one major change: no more traveling by rail, which was expensive. Instead, the team rode in automobiles and saved money by driving themselves. Even this cost-saving measure did not help, and the Black Crackers went bankrupt before the end of the 1926 season.

The Black Crackers returned to play in the NSL in 1927, opening the season with a loss and then defeating Chattanooga 7–4. The club knocked out eleven hits in their win. By midseason, the Black Crackers were back to traveling and playing local teams and still not garnering much attention in the newspapers.[fn]“Chattanooga Loses to Black Crackers,” Atlanta Constitution, 4 May 1927, 8.[/fn]

From 1928 to 1931, Atlanta had no league black team, but there were a number of local sandlot and semipro clubs that kept black baseball alive. The Atlanta Grey Sox made a short-lived league attempt in 1928, but they only played a few games before financial troubles closed them down. H. J. Peek tried again in 1930 to revive baseball with a team called the Black Panthers, but most players were content playing in the local city league. The Panthers managed to survive through the beginning of the 1931 season before the worsening depression led to them shutting down. They might have delayed their demise somewhat by being the first black team in the city to play night games at Ponce de Leon Park, which meant that fans could come after work to see the Panthers play.[fn]Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 29–30.[/fn]

Even with the history of struggles for Atlanta’s black baseball teams, the NSL granted the city another franchise in 1932. The new club got off to a rough start and never recovered, forcing the league to abandon the team in July. For example, they lost 11–1 to a rival club, the Montgomery Grey Sox, in early May.[fn]“Black Crackers Lose to Grey Sox,” Atlanta Constitution, 4 May 1932, 10.[/fn] Most of the players continued to play in the city league, which in 1933 was flourishing, led by the East City Blues and their star first baseman, Red Moore.

In 1935, the NSL met in Memphis to organize for the new season, with W. B. Baker representing Atlanta. Baker promoted other sports, such as basketball and amateur baseball, in the city and wanted to try to revive the Black Crackers. He tried something many of the earlier teams had not: he went outside Atlanta to sign players. He thought some new talent and big names might help draw in the fans. He signed Sammy Thompson from Memphis, Norman Cross from the Chicago American Giants, and George Bennette, a 16-year veteran of the Negro Leagues. The home opener looked promising: the Crackers beat the Memphis Red Sox 7–6. Unfortunately, the next few games were losses. As attendance and revenue declined, the Crackers threatened to remove the privilege of Sunday baseball at Ponce de Leon Park. A big victory and larger payday helped end that threat at mid-season. The Black Crackers managed to entice local black businesses to help them advertise, and they drew their largest crowd in a winning game against Birmingham, which convinced Cracker president Earl Mann to continue to allow them to lease Ponce de Leon Park. Their success was short lived, however, and once again the Black Crackers could not sustain the necessary fan support. By early August their season was over.[fn]Atlanta Daily World, 1 February 1935; Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 34.[/fn]

Unwilling to give up on the dream of the Black Crackers, businessman Percy Williams vowed to finance the club. After securing interest from other local businessmen, he decided to try again in 1936 but would use local talent and try to find another park to lease. Unfortunately, this revival hinged entirely on Percy Williams’ leadership, and he died unexpectedly on April 26, 1936. With the verbal support of his widow, the other owners tried to keep his dream alive. Some early victories behind the strong pitching of Snook Wellmaker kept the team afloat, but then Cum Posey signed him to a Homestead Grays contract in early June, and the ballclub floundered.[fn]Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 44–45; Atlanta Daily World, 29 May 1936.[/fn]

In 1937, filling-station owner John Harden, with his wife Billy, took over ownership of the ballclub, and the team’s fortunes improved. Harden, whose gas station was located on Auburn Avenue, got into the action due to a local feud over who had the rights to use the Black Cracker name. Other businessmen were interested in owning the rights to the team, but Harden won the day, and by 1938, the team was winning. Instead of traveling in cars to games, the team now had a bus and new uniforms. The roster also jumped to 15 players and, in some years, as high as 17. The Black Crackers played as many of their games as possible in Ponce de Leon Park, setting their schedule around the white Atlanta Crackers. Harden worked with Earl Mann to continue to lease the ballpark and to arrange payments that benefited Harden’s team. Their best financial success came when the Kansas City Monarchs came to town: fans wanted to see this famous Negro League team and its stars.[fn]Kuhn, Living Atlanta, 270.[/fn]

Harden’s first season in 1937 saw his team revive a lot of interest in Southern black baseball as his players traveled north and showed that they could compete with the Negro National League (NNL) clubs. In two contests with the Chicago American Giants, the Black Crackers won 8–2 and 6–1 respectively. After watching his team lose, Giants manager Candy Jim Taylor had nothing but praise for the Black Crackers and their solid play. He thought that the Crackers might have been the best team that the Giants had faced that season. Reporter Ric Roberts added to this praise by claiming that the Crackers’ top two twirlers, Ping Burke and Ewelosh Howard, could match the great Satchel Paige pitch for pitch. Later in the season, Manager Gainor of Hammond, Indiana, even brought in extra players for their exhibition game with the Crackers to ensure a good contest.[fn]“Atlanta Black Crackers Test Mills Sunday,” The Garfieldian, 26 August 1937, 8; “Night Game in East Chicago,” Hammond Times, 27 August 1937, 18.[/fn]

During the 1938 season, the Black Crackers joined the Negro American League (NAL). They enjoyed immediate success when they won the second-half championship before losing two games of the playoff series to the Memphis Red Sox, the first-half winners. That series ran into financial conflicts, and Negro American League president Dr. R. B. Jackson canceled the series when neither team was willing to play in the other club’s home ballpark, where their success had been limited. Since only two games were played, no season winner was declared.

The papers described the 1938 Black Cracker squad as “a team that possess [sic] small but speedy ball hawks, whose keen eye at the plate make [sic] them dangerous hitters at all times, even if they do not have the sheer power that nines like to depend on.”[fn]“Atlanta Crackers Play Chairs Thursday Night,” Sheboygan Press, 3 August 1938, 10.[/fn] Their team’s success both on the field and off seemed to rest squarely on the shoulders of their catcher, Jim “Pea” Green, described by the press as a giant of a man who could hit a ball a long way and make their pitchers look good no matter what they threw, even if it was the 6-foot-7 Duncan. The infield was anchored by Gabby Kemp, a former football star from Morris Brown who also managed the club, while the outfield had speedsters who could cover a lot of ground. The strong play of center fielder Red Hadley, who had also played football at Morris Brown, helped the Crackers win. Don Pelham, called by some the “Colored Ruth,” took care of the left-field duties, and Don Reeves, a graduate of Clark University, tracked down the ball in right field. Pelham led the team with 16 homers. Red Moore, who was later inducted into the Atlanta Sports Hall of Fame for his accomplishments, played first base. Shortstop Pee Wee Butts made the tough plays up the middle and could turn a mean double play with Kemp. Butts used a sidearm delivery and sharpened spikes to keep oncoming runners from trying to take him out.[fn]Ibid., 10; Bill Banks, “Extra Innings,” Atlanta (March 2007), 114; “Atlanta Black Crackers Boast ‘Colored Babe Ruth,’” Milwaukee Sentinel, 9 August 1938.[/fn] Their best play of the season came in August, when they beat the Monarchs in four straight contests. They immediately followed that series with a sweep of the Memphis squad that had won the first-half championship.[fn]Atlanta Daily World, 14, 16, 18 August 1938; “Atlanta Black Crackers Boast Colored ‘Babe Ruth,’” Milwaukee Sentinel, 9 August 1938.[/fn]

In 1939, due to financial troubles, the club moved to Indianapolis and played as the ABCs before returning to barnstorming. The league had wanted the club to move to Cleveland, but Harden refused. Louisville was the next suggestion, but the Louisville Black Caps did not want to share their stadium. By default, the Crackers went to Indianapolis. They quickly fell to the cellar, and little news made it back to the Atlanta papers because of the distance and cost. Harden decided to move the club back to Atlanta late in the year, and the owners of the league kicked him out for the move. Harden decided to disband the team and gave all the players their release to sign with other clubs.[fn]Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 73–74.[/fn] The next three seasons saw no professional black team play for the city. Baker left for Utah, taking his financial support with him, and Harden gave up because of his financial losses. Black baseball continued with the city league and other amateur efforts. Fans did on occasion get the opportunity to witness big-league-caliber play when Negro League teams came to town. A highlight in 1940 involved two appearances by future Hall of Famer Satchel Paige, to the delight of the locals.[fn]Atlanta Daily World, 27 May and 14 June 1940.[/fn]

By 1943, the Crackers seemed to be back on track with a solid group of young players led by their flashy shortstop, Harvey Young from Baltimore. Young joined center fielder Dave Harper, left fielder Fred Sheppard, and right fielder Dusty Owens in what the press dubbed Atlanta’s “murderers’ row.” Eugene Jones and Adolphus Grimes helped by making the all-star team. The team spent a hefty sum purchasing new players to regain their reputation in black baseball. John Harden was convinced by other local businessmen to get involved again, and they built a team made up of the best players from the Atlanta All Stars and the Scripto Black Cats, sponsored by the Scripto Pencil Factory, known infamously as the scene of the 1913 murder of Mary Phagan. The club played independently and used Northern booking agents to help them organize contests that would prove profitable. They began the season with a 9–6 victory over the Cincinnati Clowns. They played in a three-team doubleheader at Yankee Stadium in August, taking on the St. Louis Stars and the New York Black Yankees.[fn]“Atlanta Black Crackers Make New York Debut Sunday,” Afro-American, 14 August 1943; “Colored Game Here Tonight,” Gastonia Daily Gazette, 22 July 1943, 9; Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 83–84; Stephen J. Goldfarb, “The Slaton Memorandum” American Jewish History 88, no. 3 (2000), 325–39; “Black Cracker Aces to Play for All-Stars,” Atlanta Constitution, 30 September 1943, 15.[/fn]

Due to the financial success the Black Crackers had in 1943, the club returned in 1944 with high expectations. The opening-day gala started with a band concert that the club hoped would attract 12,000 fans. John Harden became part owner of the New York Black Yankees and planned to use that relationship to help the Atlanta Club secure opponents. One of the highlights came early in the season, when the Black Yankees came to town, with Satchel Paige expected to make a guest appearance. Unfortunately Paige never showed up, but 6,000 fans came for the game and stayed. Harden offered special discounts to soldiers and their families, and he extended promotional efforts such as family days to encourage fan attendance. To keep the park owners happy, Harden encouraged the Crackers ownership to book other teams into Ponce de Leon Park when there were open dates. Felix Manning pitched a no-hitter against the St. Louis Stars and won 5–0. He came back to lead the Crackers to victory in the second game of the doubleheader, taking over in the third inning as the Black Crackers won 5–3. Another highlight came when the club got a chance to play in the Polo Grounds in September, although they lost to the New York Cubans, 16–5.[fn]“Black Crackers Plan Gala Opening,” Atlanta Constitution, 6 May 1944; “Black Cracker Pitcher Hurls No-hitter,” Atlanta Constitution, 1 June 1944; “Lose to NY Cubans,” Baltimore Afro-American, 12 September 1944.[/fn]

In 1945, Harden had the luxury of being invited to join two leagues. He chose the NSL because of the close geographic proximity of the other league entrants. He was made treasurer of the league; Dr. Jackson served as president. As treasurer, Harden hoped to work with Jackson to create a favorable schedule for his Crackers. Led by some big bats and a stellar pitching staff, the Black Crackers won both halves of the season and were declared the NSL champions. They defeated Knoxville in the first half by two games.[fn]“Homestead Grays at Forbes Field Friday Night,” Monessen Daily Independent, 23 July 1945, 5; “Atlanta and Ashville Negro Clubs Meet at Stadium Sat. Night,” Gastonia Daily Gazette, 10 August 1945, 9; “Southern Clubs Form new Baseball League,” Atlanta Daily World, 17 February 1945; “Southern Baseball League Formed with Eight Team Slate,” New York Amsterdam News, 17 February 1945.[/fn] Manager Sammy Haynes guided the team to their early-season triumphs and brought back most of the team intact for the 1946 season, when they hoped to repeat their initial success. In both seasons, clean-up hitter Lomax “Fence Bustin’” Davis led the team offensively while southpaw Robert Branson anchored the pitching staff, relying on the solid play calling of catcher Harry Barnes.[fn]“Here Are Hurling and Batting Aces of Atlanta Nine,” News Palladium, 30 July 1946, 5; “Atlanta Club Boasts All Southern Talent,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 24 July 1945.[/fn]

When the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson at the end of the 1945 season, interest in baseball around Atlanta in 1946 surged, as it did in many places. Fans were excited by the changes taking place in baseball, and the black community wanted to see their stars play in the majors. Vernon Jordan recalls getting a chance to see Robinson play at Ponce de Leon Park in April 1949. “Robinson’s arrival was a big moment, and there was no way my father, Windsor, or I would have missed it. We went to Ponce de Leon Park, thrilled at the prospect of getting a glimpse of Robinson.”[fn]Vernon Eulion Jordan Jr. et al., Vernon Can Read! A Memoir (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2002), 57.[/fn] The opening game, between the Dodgers and the white Atlanta Crackers, drew an overflow crowd of 15,119 fans, including more than 5,000 blacks, at Ponce de Leon, which seated only 14,500. Large crowds did not always come out to see the Black Crackers play the Homestead Grays, Cleveland Buckeyes, and other Negro League opponents. Barnstorming and playing league contests during the 1946 season kept the Black Crackers alive and hoping for a good 1947 team, under new management.

John Harden saw the large crowds who came out to see Robinson play and did not know how that might affect his ballclub in the long term. He worried that the integration of the majors might hurt Black Crackers attendance, so he sold a portion of his shares in the club to local businessman Claud Malcolm. Harden made other changes as well. Sammy Haynes gave way to Bill Perkins as player/manager. As a veteran catcher, Perkins brought a strong knowledge of his own hurlers and opposing batters to the helm along with a savvy gained while playing with the Philadelphia Stars and New York Black Yankees and catching Satchel Paige.[fn]“Jacksonville Eagles to Be Saturday Foe,” Chester Times, 1 August 1947, 14; Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers, 100.[/fn] While no final-season records have been found, the Black Crackers further solidified their reputation as one of the finest Southern ballclubs in the country with solid play against a range of opponents such as the Birmingham Black Barons, the Indianapolis Clowns, the Jacksonville Eagles, and others.

The Black Crackers’ fine play carried over into 1948 under their manager Curry and their sensational rookie pitcher “Double Duty” Wyndner, an 18-year-old phenom. Reporters claimed his fastball kept hitters guessing, and he was also a consistent hitter at the plate. The Black Crackers joined the NSL in place of the Danville Aces, but by midseason they had gone back to barnstorming as a more lucrative opportunity. With the help of the radio, fans could now follow the pitching exploits of their ace “Lefty” Bell even when the Black Crackers were on the road. Bell won 15 games for the team in 1948.[fn]“Southern Negro Nine Face Buds at 8:30,” News Palladium, 7 July 1948, 10; “Black Crackers Will Play Here,” Miami News, 14 August 1948.[/fn]

In 1949, the Black Crackers got some new competition: a new club that became the Atlanta Stars (formerly the Scripto Black Cats) and compiled a 42–10 record by midseason. The Stars benefited from the reputation of the Black Crackers, as their opponents clearly respected them and were willing to book games with them. A Michigan writer before a game in Benton Harbor described the Stars as “loaded in the pitching department and bringing in themselves an array of fine hitters.”[fn]“Colored Nine Will Invade Colony Park,” News-Palladium, 12 July 1949, 10.[/fn] The leading player on the club was infielder Harry Hatcher, a former college player at Alabama A&T, while the pitching staff boasted the services of former Memphis pitcher William Morgan and former Black Barons hurler John Wade. This would be the last season for this Atlanta ballclub, as black baseball gave way to the integration of the major leagues and the growth of television, which allowed fans to follow their favorite players wherever they played. The Atlanta Cubans replaced the Stars and played through 1952 before also folding due to financial struggles.

After the Crackers called it quits in the Negro Leagues, for many years, few wrote or talked about the team or the leagues. It was not until Robert Peterson’s book Only the Ball Was White revived an interest in the Negro Leagues that researchers started looking for the old players and their stories. This focus led people to well-known teams such as the Kansas City Monarchs and Homestead Grays and eventually to lesser-known clubs like the Atlanta Black Crackers. Former player George McFadden explained why people should be interested in the Crackers in a 2005 interview, saying, “I shut out the Atlanta Black Crackers, and they had a big name. They was a big name in baseball.”[fn]Ed Gordon, interview with George McFadden, NPR, 2005.[/fn] The city of Atlanta responded to this interest.

A reunion of Southern ball players from Atlanta, Memphis, and Birmingham took place in Atlanta in 1989. The weekend celebration was called the “Living Legends of Baseball.” Players were honored between games at Atlanta Fulton County Stadium. One of the players present was Chico Renfroe, who helped push the idea for the celebration. In 1990, the Alliance Theater also recognized the former Black Crackers players at the premier of August Wilson’s play Fences. Again, one of the players present was Chico Renfroe, star shortstop of the Kansas City Monarchs, who went on to become a writer for the Atlanta Daily World and a radio broadcaster for WIGO. Renfroe got his start in the Negro Leagues as a batboy for the Black Crackers.[fn]Donald Lee Grant et al., The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press), 546; “Veterans of Negro Leagues Revisit the Bad Old Days, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, 4 June 1989, C1; “Former Negro League Stars Gather for Reunion, Tribute,” Gadsden Times, 5 June 1989; “In a League of Their Own,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, 2 February 1990, C1.[/fn] These were opportunities for the city to say thanks for the fine talent of the Black Crackers and other local black teams who played in the city for over 30 years. These reunions and other such gatherings have also helped rekindle an interest in the history of black baseball in Atlanta and the rest of the country.

LESLIE HEAPHY, associate professor of history at Kent State University, Stark Campus, has written or edited four books on the Negro Leagues and women’s baseball. She is editor of the peer-reviewed journal “Black Ball: A Journal of the Negro Leagues.”

PARTIAL PLAYER LISTS

The list that follows is not complete.[fn]31. These rosters were compiled by the author from a variety of newspapers and other sources: Atlanta Constitution; Atlanta Daily World; Chicago Defender; Joyce, Atlanta Black Crackers; Gastonia Daily Gazette; Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited: Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000); Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; Milwaukee Sentinel; and Pittsburgh Courier.[/fn] There are no official records of the Black Crackers, and newspapers such as the Atlanta Daily World did not become dailies until 1932. Northern African American papers such as the Defender and Courier did not tend to cover the NSL teams unless they were playing one of the major black teams. This list is meant to give readers and researchers a glimpse of the talent and to show how much research still needs to be done to tell their story.

| Alexander (p) 1921 | Glenn, Oscar Pap (3b) 1937-38 | Neal, Bobby (of) 1947 |

| Allen, Little Satchel (p) 1943 | Golden, Claude (p) 1947 | Neal, Charlie (2b) 1947 |

| Anderson, (p) 1926 | Green, Jimmy Pea (c) 1935-38 | Neal, Jimmy (ss) 1947 |

| Barnes, Harry (c) 1944-45 | Grier, Eddie (c) 1949 | O’Neal (c) 1921 |

| Barnhill, Herbert (c) | Grimes, Adolphus Happy (of/1b) 1943 | Owens, Dusty (of/2b) 1943, 1946, 1949 |

| Baynard (c) 1920 | Grimes (c) 1921 | Peatross, Maurice (1b) 1947 |

| Bell, Lefty (p) 1948 | Hadley, Red (cf) 1937-38 | Pelham, Don (of) 1938 |

| Bennette, George Jew Baby (of) 1935 | Hampton (of/p) 1921 | Perkins, Bill (mgr/c) 1947-1949 |

| Bird, Early (c) 1947 | Harp, Johnny (3b) 1948 | Perry, Alonzo (p) 1945 |

| Boone, Oscar, 1939 | Harper, Dave T. (of) 1943, 1946-47 | Phillips, Richard (p) 1949 |

| Boyd, Lincoln Linky (2b) 1948-49 | Harris, Ben (p) 1921 | Pritchett, Drew (p) 1943 |

| Branson, Robert Bob (p/of) 1946-47 | Hatten (c) 1947 | Randolph (p) 1938 |

| Brichett, Dee (p) 1943 | Hatcher, Harry (ss) 1949 | Ray, Johnny (1b/of) 1947 |

| Brigham, Eddie (of) 1947 | Haynes, Sam (c/mgr) 1946 | Reid, Ambrose (util) 1920-21 |

| Bunn, Willie (p) 1943 | Henderson (p) 1925 | Renfroe, Othello Nelson Chico (ss/batboy) |

| Burke, Ping (p) 1937-38, 1946 | Hicks, Alonzo (of) 1947 | 1938, 1950 |

| Butts, Thomas Pee Wee (ss) 1938 | Hill (p) 1937 | Reese, Slim 1937 |

| Byrd, Charley (3b) 1946 | Holder, William (2b) 1949 | Reeves, Donald Rabbit (of) 1935-39 |

| Christopher, Thaddeus (c) 1947 | Holiday, Flit 1935 | Richardson, Johnny Dude (ss) 1947-48 |

| Cleveland, 1920 | Holmes, Phil (of/3b) 1947 | Robinson (p) 1921 |

| Coleman, Melvin Slick (p) 1944-47 | Howard, Twelosh (p) 1937-38 | Sadler, John (p) 1945 |

| Colzie, James (p) 1938-40 | Humphrey (of) 1937 | Sampson, Ormand (ss/mgr) 1937-38 |

| Cornelius (p) 1925 | Idlett, Arthur Kid (3b) 1925 | Sayler, Al Greyhound (1b) 1939 |

| Cooper, Bill Flash (c) 1938, 1946 | Ingram, Alfred (p) 1949 | Sheppard, Fred (of) 1943, 1947 |

| Cottingham (of) 1920 | Jackson, Bob Bozo (ss/2b/3b) 1944-48 | Smith, Chip Tiny (util) 1938 |

| Cowan (inf) 1920 | Jefferson, Ellison (c) 1946 | Smith, Milton (2b) 1948 |

| Cross, Norman (p) 1935 | Johnson (p) 1920 | Smith (of) 1921 |

| Curry, Homer (p/of/3b) 1948 | Jones, Eugene (p) 1943 | Steward, Bob (of) 1945-46 |

| Daniels, Jumping Joe (p) 1926 | Jones, Ralph (p) 1948 | Stewart, Richard (of) 1949 |

| Davis, Lomax Butch (of) 1944-46, 1948 | Kemp, James Gabby (2b) 1937-39 | Stokes, Jim (c) 1943 |

| Davis, James, 1945 | Kendrick, Leo (c) 1943 | Streeter (p) 1921 |

| Davis, Big Preacher (2b) 1921 | King, Brennan Early (p) 1944-47 | Swanson, Roy (c) 1948 |

| Davis, Spencer (3b) 1938 | Lacey, Raymond (3b) 1947 | Terrell, Bill (3b) 1946-48 |

| Dixon, Bullet (p) 1938 | Linarn, Boyd (of) 1948 | Terry (of) 1948 |

| Dixon (of) 1921 | Lomax, Butch Fence Bustin (of) 1946 | Thompson, Sammy (inf) 1935 |

| Duncan (p) 1938 | Long, Ernie (p) 1947 | Thompson, Will (p) 1945 |

| Echols, Melvin Sunny Jim (p) 1943, 1947 | Lumpkin, Norman Geronimo (of) 1938 | Thorton, Jack (p, 1b/2b) 1937 |

| Edwards (p) 1925 | Manning, Felix (p/mgr) 1944 | Torriente, Cristobal (of) 1934 |

| Ellison, Roy Early Bird (c) 1946, 1948 | Marlin, Martee (p) 1925 | Wade, John (p) 1949 |

| Emerson, Carl (ss) 1946 | McCarver (p) 1921 | Welch, James Ike (1b) 1948 |

| Evans, Chin (p) 1937-39, 1943 | McCoy, Andy (p) 1943 | Wellmaker, Leroy Snook (p) 1936-37, 1943, |

| Favors, Tom Monk (1b) 1945-46 | McFarland, John (p/3b/2b) 1943, 1948 | 1945 |

| Ferrell, Willie (p) 1938 | Means, Louis (ss) 1921 | Wesley, Two Sides (ss) 1921 |

| Fisher, Tipper 1921 | Merritt (p) 1946 | Williams, Nish (p/mgr) 1925, 1938, 1943 |

| Fletcher, George (1b) 1943 | Michael (2b) 1947 | Williams, John (p) 1948 |

| Foster, John (p) 1937 | Monroe, Lee (1b) 1949 | Wyatt, Leon (p) 1946-47 |

| Franklin, Henry (p) 1949 | Moore, James Red (1b) 1938-39 | Wyndner, Double Duty (p/c/of) 1948 |

| Frederick (p) 1920 | Moore, Terry (of) 1948 | Yancey, William James Bill (mgr) 1945-46 |

| Gilliam, Ted (1b) 1920-21 | Morgan, William Sack (p) 1949 | Young, Harvey (ss) 1943 |

| Gissentanner (p) 1921 | Murden, Shugarty (2b/of) 1921 | Zapp, Jim (Lf) 1947 |