Chipper Jones

For generations, many American fathers have raised their sons with dreams of emulating their baseball hero, Mickey Mantle. Chipper Jones’s father was no different. From an early age, his son reminded him of The Mick: a small-town country boy with charming good looks, a Southern drawl, and a preternatural ability to hit a baseball from both sides of the plate.

For generations, many American fathers have raised their sons with dreams of emulating their baseball hero, Mickey Mantle. Chipper Jones’s father was no different. From an early age, his son reminded him of The Mick: a small-town country boy with charming good looks, a Southern drawl, and a preternatural ability to hit a baseball from both sides of the plate.

“As a kid, I didn’t even know what Mantle looked like,” Jones said. “I only heard my dad talk about him. I just thought he had to be the coolest guy ever because he had the coolest name ever.”1

Mantle’s story was already the stuff of legend before Jones ever picked up a bat: his prodigious power and speed, his string of never-ending injuries and — despite an overwhelmingly successful career by any measure — his struggle to live up to fans’ folk-hero expectations of him on and off the field.

No baseball player has followed Mickey Mantle’s path more closely than the cocky kid from Pierson, Florida. Groomed for superstardom, with a cool nickname to match his father’s Hall of Fame idol, Jones exceeded even the lofty goals that had been set for him from the beginning. The Atlanta Braves selected him as the No. 1 pick in the 1990 amateur draft and over the next two decades, he helped lead the franchise to its greatest heights, winning a World Series in his rookie season, earning the National League’s Most Valuable Player award, and becoming the face of a baseball dynasty.

“I never wanted to play anywhere else,” Jones said. “I’m a Southern kid, and I wanted to play in a Southern town where I felt comfortable. And I felt comfortable from day one in the Braves organization.”2

After announcing his retirement in 2012, the Braves third baseman was so respected around the major leagues that opposing teams showered him with gifts on a ceremonial farewell tour. He even drew ovations in Mantle’s adopted hometown of New York, where he had tormented Mets and Yankees fans for so long with an inordinate supply of game-winning hits. In turn, they enjoyed heckling the brash Atlanta star for his outspoken comments and the revelation of an adulterous affair that tarnished his image early in his career.

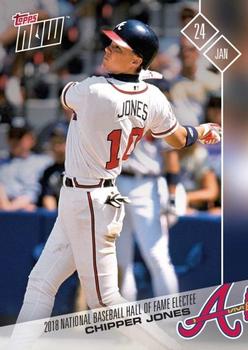

Over the years, Jones’s off-field troubles receded from the spotlight as he built his credentials for Cooperstown. With 468 home runs and 2,726 hits, Jones stands alongside Mantle as one of the greatest switch-hitters the game has ever seen, ranking near the top of almost every major offensive category for players who batted from both sides. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2018 in his first year of eligibility. In receiving 97.2 percent of votes from the baseball writers, he ranked behind only George Brett among third basemen in the sport’s history.

Almost from the moment Larry and Lynne Jones’s only son was born on April 24, 1972, in DeLand, Florida, Larry Wayne Jones Jr. looked so much like his father that a relative described him as a “chip off the old block”3 — and he was called Chipper from then on. The Joneses lived on a 10-acre leatherleaf fern farm in nearby Pierson, a small, blue-collar town known as the “Fern Capital of the World.” Larry Sr., who had played baseball at Stetson University, was a math teacher and varsity coach at Taylor High School and Lynne was a professional equestrienne. “Our den was full of her trophies,” Chipper said. “She had that little strut about her, that little look in her eye.”4 His father taught him how to play baseball, but he learned to carry an attitude of what his mother called “necessary arrogance” from watching her ride dressage horses in competition.

Larry painted a strike zone on the back of a wooden garage at Lynne’s horse farm and pitched tennis balls or Wiffle balls to young Chipper. “We’d get out there and throw the ball just as hard as God let us,” Larry said.5 They would play one-on-one games in the backyard, running through the lineup of the Los Angeles Dodgers, father and son’s shared favorite team. When Steve Garvey or Ron Cey came up, Chipper would bat right-handed like the real major-leaguers did. When Reggie Smith or Ken Landreaux was up, he would switch to the left side. By the time Chipper was 11 years old, his father could no longer beat him in their backyard games.

Jones’s natural right-handed swing led him to step “in the bucket” toward third base, a bad habit he was never able to break. Larry suggested that he add a toe tap before starting his swing to keep his timing and balance intact; that became a signature element of his hitting style, mimicked by young players6 all over the Atlanta area. “Nobody knew my swing inside and out like [my dad],” Chipper said later. “He built it.”7 Throughout his career, whenever Jones was in a particularly frustrating slump, he called Larry Sr. for help first. The Braves’ hitting coaches learned to step aside for the one person who could always find whatever flaw was in Chipper’s swing and fix it. “It got to be almost comical how hot I got every time Dad came to town,” he said. “The Braves should have put him on the payroll.”8

One of Jones’s first breakout moments came at age 12, when he hit three home runs in a game against a powerhouse team from Altamonte Springs that included future major-leaguer Jason Varitek. Altamonte Springs won and advanced to the Little League World Series, but Jones’s performance turned heads.9 By the time he reached the eighth grade, Jones was good enough to play on the varsity team at Taylor High School. His father quit his job as the school’s baseball coach to ward off any complaints about favoritism, but Jones’s talent was plain for all to see.

After his freshman year, Jones transferred to a prestigious private academy, The Bolles School, about 100 miles away in Jacksonville. His parents thought his teachers at Taylor were cutting him too much slack because of his athletic prowess. “He was making straight A’s and he never cracked a book,” Lynne said.10 As a self-described country boy, Jones didn’t fit in well at Bolles. Despite being named starting quarterback11 on the football team as a sophomore, he quickly grew overwhelmed and homesick. “I went … from a one-stoplight town to a big city, pulling into a parking lot full of better cars than I drove and a lot of rich kids,” he said. “It was tough, a big growing-up process.”12

Jones eventually grew more comfortable, but his move to a private school alienated some of the old friends he had grown up with in Pierson. “I felt like a traitor the first time I went back,” he said. “You could see the contempt on people’s faces.” His Bolles team eliminated Taylor High in the playoffs in three consecutive seasons. Jones never forgot his mixed feelings about leaving home, and he said those memories strongly influenced his decision not to test free agency and stay with the Atlanta Braves during his entire professional career.13

During Jones’s senior year, dozens of major-league scouts attended his games and even his private batting-practice sessions in the hitting cage. His baseball coach, Don Suriano, tried to shield him from all the attention but it was a futile effort. Jones was named as the Florida state player of the year after hitting .488 as a switch-hitting shortstop; he also went 7-3 with a 1.00 ERA as a pitcher.

The consensus top pick in the amateur draft, and the national high school player of the year, was pitcher Todd Van Poppel from Arlington, Texas. The 6-foot-5 right-hander was armed with a 95-mph fastball and a big curveball; he was already drawing comparisons to fellow Texans Nolan Ryan and Roger Clemens. The Atlanta Braves held the No. 1 selection, but Van Poppel made it clear that he would not sign with the lowly Braves — or anyone else. He planned to attend the University of Texas, Clemens’s alma mater. The Braves had finished last in the NL West in three of the last four years and were on their way to 97 losses and another last-place finish in 1990.

“We all heard that Todd Van Poppel didn’t want to play here,” said Braves pitcher and future Hall of Famer Tom Glavine, who was in his fourth big-league season then. “I think we all took it personally. I think we were all like ‘Okay, screw you. We don’t want you to play here.’ ”14

Jones and Van Poppel had met each other once before, when they both visited the University of Miami at the same time. Neither could have imagined they would be linked together in baseball history. “If Todd Van Poppel didn’t want to be an Atlanta Brave,” Jones said later, “I was more than happy to take his place.”15

Braves scouts Tony DeMacio and Dean Jongewaard met with the Jones family the day after his high school graduation to begin salary talks. But Chipper had no interest in starting off on the wrong foot with the Braves. “The Braves want to get their number one player signed, sealed, and delivered,” he said. “I’m not out to hold up any ball club.”16 He settled for a $275,000 signing bonus — nearly a million dollars less than Van Poppel got from the Oakland A’s as the No. 14 pick in the same draft.

Jones joined the Braves’ rookie-league camp in Bradenton, Florida, about a three-hour drive from his hometown of Pierson. But a hand injury suffered during a fight with a high school teammate hampered his swing and he hit just .229 in 44 games. In a desperate attempt to improve his batting average and his confidence, he received permission from manager Jim Procopio to hit right-handed for a few games. That decision angered the Braves’ brass and cost Procopio his job. They didn’t care about the 18-year-old phenom’s stats, only his development.

Jones joined the Braves’ rookie-league camp in Bradenton, Florida, about a three-hour drive from his hometown of Pierson. But a hand injury suffered during a fight with a high school teammate hampered his swing and he hit just .229 in 44 games. In a desperate attempt to improve his batting average and his confidence, he received permission from manager Jim Procopio to hit right-handed for a few games. That decision angered the Braves’ brass and cost Procopio his job. They didn’t care about the 18-year-old phenom’s stats, only his development.

Jones spent the fall of 1990 in an instructional league at West Palm Beach, where he met Hall of Famer Willie Stargell and former Washington Senators slugger Frank Howard, who were both working for the Braves as hitting instructors. Stargell recommended that he use a bigger, heavier bat, advising him that his body would catch up soon, which it did as he filled out to 6-foot-4 and 210 pounds. “We’ll have you hitting 30 homers in no time, son,” Stargell said. Jones called his dad to ask for a second opinion. “When Willie Stargell tells you something,” Larry said, “you respect him enough to heed that advice.”17

Jones’s hitting quickly came around — in his second pro season, with Single-A Macon, he hit .326 with 15 homers, 24 doubles, 11 triples, and 40 stolen bases — but his fielding at shortstop left a lot to be desired. He made a whopping 71 errors in 135 games and worked hard every day with infield coach Carlos Rios to get his defense up to a major-league level. Still, his bat was already strong enough that Baseball America named him as the minor leagues’ No. 4 prospect entering the 1992 season.18

After starting the year in High-A with the Durham Bulls, Jones was promoted to the Braves’ Double-A affiliate in Greenville, South Carolina. Managed by future Boston Red Sox skipper Grady Little, the G-Braves were loaded, with future major-leaguers Javy Lopez (the league MVP), Tony Tarasco, and Pedro Borbon on the roster. The Braves finished 100-43, won the Southern League championship, and were recognized by Minor League Baseball as one of the greatest teams of all-time.19 The 20-year-old Jones did his part, hitting .346 with a league-best 11 triples in 67 games.

Jones missed a playoff game that fall for a reason he later regretted — to get married. His bride, Karin Fulford, was a Wesleyan College student that he had met in Macon the year before. They wed on September 12, 1992, as his teammates were playing the Chattanooga Lookouts in the championship series. Neither the Braves nor Jones’s parents were happy with his decision, and the bad timing foreshadowed an unhappy marriage.

The following year, Jones was back in the playoffs with Triple-A Richmond on the day he learned the Braves were bringing him up to the big leagues. He made his debut on September 11, 1993, as a ninth-inning defensive replacement at shortstop in a blowout win at San Diego. The Braves were in the middle of one of the most dramatic pennant races in National League history, needing every one of their 104 victories to overtake the San Francisco Giants and win the West Division by a single game.

The rookie Jones soaked up the atmosphere — “I had the best seat in the house,” he said20 — but didn’t see much playing time. He recorded his first hit on September 14 at home in Atlanta, a pinch-hit single batting right-handed against Cincinnati Reds lefty Kevin Wickander. But he only had two other at-bats in the season’s final three weeks. Manager Bobby Cox left him off the playoff roster, but invited him to travel with the team to Philadelphia for the NL Championship Series. The Braves, gassed from the tension of a tight pennant race, lost to the Phillies in six games.

Jones entered spring training in 1994 preparing to back up the veteran Terry Pendleton at third base and split time at shortstop. Then left fielder Ron Gant broke his leg in a preseason motorcycle accident, opening a position in the Braves’ starting lineup. Jones began working out in the outfield, a position he had only played sparingly as a teenager, learning the ropes from Deion Sanders and Otis Nixon. He was having a strong spring, hitting .375 with three home runs, when he was seriously injured two weeks before Opening Day.

On March 18, in an exhibition game against the New York Yankees, Jones attempted to avoid a tag while running to first base when he heard his left knee pop. The diagnosis was grim: a full tear of the anterior cruciate ligament, ending his promising season before it had even begun. The 1994 season ended prematurely for everyone in August when major-league players went on strike and the World Series was cancelled because of the ongoing labor dispute. Jones had to wait through an excruciatingly long offseason before he could get back on the field.

On April 26, 1995, Jones finally saw his name in the Braves’ starting lineup, playing third base and batting third in the order — wearing his favored No. 10 jersey for the first time, the same number his dad had always worn. Only two-thirds of the seats were filled at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium as fans reluctantly welcomed back the striking major-league players, but “I wasn’t going to let anything ruin my first Opening Day,” Jones said.21

Jones’s excitement was so overwhelming that he ran over his starting pitcher, Greg Maddux, on an infield popup by the Giants’ Barry Bonds in the first inning. The reigning Cy Young Award winner verbally berated him on the field and in the dugout for the next few innings: “Settle the [expletive] down, you [expletive] rookie!”22 Jones redeemed himself a few minutes later by driving in the Braves’ first run of the season with an RBI single. He added another RBI single and scored three runs in the season opener. Thirteen months after a devastating knee injury, his hard work was about to pay off in a big way.

There was no more fitting place for Jones to hit his first home run than at Shea Stadium. With the Braves’ move to the NL East division following baseball’s realignment in ’94, their growing rivalry with the New York Mets turned into one of the sport’s most heated matchups for the rest of the decade. Jones, who often seemed to save his best performances for games against the Mets, would later find himself at the center of New York fans’ ire both on and off the field.

His first of many game-winning hits against the Mets came on May 9. Batting left-handed against Josias Manzanillo, Jones broke a 2-2 tie in the ninth inning by lining a fastball into the upper deck in right field. “I don’t think my feet hit the ground the whole time I was rounding the bases,” he said.23 That first home run opened the floodgates: he went deep four more times in the next seven games. Less than a week later, he hit a walk-off home run against the Florida Marlins’ intimidating closer, Robb Nen. That stretch, he said, helped him turn a corner: “I went from questioning if I belonged to knowing I did.”24

Jones couldn’t sustain that kind of hot streak all season, but he finished with a solid .265 average, 23 home runs, and 86 RBIs as the Braves ran away with the NL East by 21 games. In a controversial Rookie of the Year vote, Jones finished runner-up to Japanese sensation Hideo Nomo of the Los Angeles Dodgers. The 26-year-old Nomo had pitched for five years in Japan’s top-flight league before coming over to MLB as a free agent and leading the National League in strikeouts in his first season.

Jones may have missed out on the individual honor, but he and the Braves had greater heights to climb in the postseason. Major League Baseball had added a new wild-card team and an extra round of playoffs, and Jones’s debut in the NL Division Series against the Colorado Rockies was one to remember. In Game One at a sold-out Coors Field in Denver, he hit a home run in the third inning and made a diving stop of Andres Galarraga‘s line drive in the eighth to help preserve a 4-4 tie. Then in the top of the ninth, he drilled a hanging slider by Curt Leskanic over the wall in right-center field to give the Braves a crucial 5-4 win to open the best-of-five series.

Atlanta downed the Rockies in four games and Jones again made an impact in Game One of the NLCS against the Cincinnati Reds. With the Braves down 1-0, the rookie third baseman led off the ninth inning with a single off Reds lefty Pete Schourek and scored the tying run two batters later on a groundout. The Braves won the series opener in 11 innings and went on to sweep the Reds to clinch the National League pennant, their third in the past five years. Jones recorded a base hit in each of his first eight playoff games, and batted .308 in that postseason. “I’ve been through a lot of pressure games in my life,” he said. “Some guys live for crunch time. I’m one of them.”25

Jones played solidly in the World Series against the Cleveland Indians, reaching base three times in the 1-0 victory in Game Six that secured the Braves’ first championship since moving to Atlanta in 1966. After Marquis Grissom caught the final out in center field, Jones was the first player to reach the mound and join the celebration with closer Mark Wohlers and catcher Javy Lopez. He ended up at the bottom of the dogpile; it was “the best pain you’ll ever experience in your life,” he recalled.26

The Braves secured Jones’s services for four more years by signing him to an $8.25 million extension during the offseason.27 His salary jumped from $114,000, near the league minimum in ’95, to $825,000 a year later, and his financial woes during the dark days of the strike — when he and wife Karin had to borrow money from her family to pay the bills28 — were long gone.

That security off the field led Jones to more greatness on the field in 1996, when he hit 30 home runs and began an eight-year streak of 100 or more RBIs as the Braves won their second consecutive NL pennant. Jones was selected by Bobby Cox to his first All-Star team that summer, along with five of his teammates, and he started at third base in place of the injured Matt Williams. Jones finished fourth in the MVP voting behind San Diego’s Ken Caminiti.

The Braves quickly disposed of the Los Angeles Dodgers in the NL Division Series, then fell behind the St. Louis Cardinals three games to one in the league championship series. Dennis Eckersley‘s fist-pumping histrionics in closing out Game Four fired up the Braves’ offense and the defending champions pummeled the Cardinals in the next three games, outscoring St. Louis 32-1 to win the NLCS. Jones hit .440 during the series.

After sweeping the New York Yankees on the road in the first two games of the World Series, the Braves looked well positioned to win back-to-back titles and stake their claim as one of baseball’s great dynasties. “We were the hottest team on the planet,” Jones said. “Then all of a sudden, we weren’t.”29 The Yankees won all three games in Atlanta, rallying from a 6-0 deficit in Game Four on Jim Leyritz‘s game-tying home run, and closed out the Braves in Game Six at Yankee Stadium. Jones was left standing on deck with the tying and go-ahead runs on base as Mark Lemke popped out to end the Series.

The Braves began the 1997 season with a new home stadium, Turner Field, and a new roster, having traded away team leaders David Justice and Marquis Grissom to the Cleveland Indians in a blockbuster deal before spring training. The outspoken Justice, who had hit the World Series-clinching home run for the Braves in 1995, had been Jones’s mentor, his “big brother” in the clubhouse. After the trade, Justice said, “The team is Chipper’s now.”30

When the Braves moved into Turner Field, they also began a new game-day tradition, allowing players to select their own “walk-up” music before their at-bats. The song Jones chose, Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train,” became associated with him for the rest of his career. In his autobiography, Jones gleefully reminisced about digging in against the rival Mets and hearing catcher Mike Piazza express his disgust under his breath when the iconic opening guitar riff blasted throughout the stadium. “He didn’t hate the song,” Jones recalled. “He hated the spectacle of what might happen when I got into the box.”31

Jones’s exploits against the Mets soon became the stuff of legend. As the Braves-Mets rivalry heated up, New York fans increasingly focused their wrath on Jones, who gave them plenty of ammunition when his troubled personal life went public during the 1998-99 offseason.

With his marriage to Karin crumbling, Jones decided to come clean by giving an interview in which he admitted to having multiple affairs and fathering a child with a waitress from a Hooter’s restaurant whom he met during spring training. “I’ve messed up royally,” he said. “I wish you were allowed one mulligan in life. To be able to rewind two years and play it all over again, I’d do it in a heartbeat.”32 The revelation shattered his all-American image and it took years for his reputation to recover. Visiting fans heckled him mercilessly and he sometimes wore cotton in his ears to muffle the boos.

Nowhere were the boos louder than at Shea Stadium in New York. Mets fans took to chanting Jones’s given name — “Lar-ry! Lar-ry!” — after pitcher Orel Hershiser mentioned in an interview that the Braves’ star hated being called by that name.33 Piazza added to the furor when he told a reporter he couldn’t “call a grown man Chipper.”34

Jones shrugged off the fans’ enmity and his own personal issues to deliver a career-defining MVP season in 1999. A tip from the Braves’ new hitting coach, Don Baylor, helped transform his game. Despite being a natural right-hander, Jones had only hit 12 of his 108 home runs thus far against lefty pitchers, and NL managers learned to take advantage of his weakness by turning him around to bat righty in crucial situations. Baylor pushed him to develop the same confident attitude — the “necessary arrogance” his mom had long ago instilled in him — from either side of the plate.

The new mind-set paid dividends immediately, as Jones hit his first home run of the 1999 season off the Arizona Diamondbacks’ left-handed ace, Randy Johnson. He went on to hit .352 with a career-high 15 homers from the right side that year, setting an NL record for most home runs (45) by a switch-hitter. But he saved his most damaging blows for the Braves’ bitter rivals from New York.

In late September, the Mets came to Atlanta just one game back in the NL East standings with 12 to play. Six of those games were against the Braves, and Jones made the most of his first real pennant race. In a memorable three-game sweep at Turner Field, Jones hit four home runs — two from each side of the plate, every one of them giving the Braves a lead. A week later, he reached base five times in three games as the Braves took the return series at Shea Stadium and cruised to the division title.

Jones’s dominance against the Mets propelled him to NL MVP honors at the end of the season; he received 29 of 32 first-place votes from the baseball writers after batting .319 with 116 runs scored, 110 RBIs, and setting career highs in home runs (45), walks (126), and stolen bases (25).

But he wasn’t quite finished with the Mets, and New York fans weren’t done with “Larry.” The Mets regrouped to take the National League’s wild-card playoff berth, then they upset the 100-win Arizona Diamondbacks in the division series to set up an intense rematch with the Braves in the NLCS.

The Mets’ brash manager, Bobby Valentine, had spent the final weeks of the regular season accusing the Braves of underhanded tactics, including tipping pitches to their hitters, and there was no love lost between the two teams. Jones added fuel to an already blazing fire when, after enduring hours of hostile taunting from the Shea Stadium faithful, he snapped back to a reporter, “Now all those Mets fans can go home and put their Yankees stuff on.”35

In the NLCS, with boos and “Lar-ry” chants raining down on him every time he stepped into the batter’s box at Shea Stadium, Chipper reached base in 15 of his 29 plate appearances (four of his nine walks were intentional), but only recorded one RBI. The Braves won a tense series, clinching the pennant on Andruw Jones’s bases-loaded walk in the 11th inning of Game Six.

The World Series against New York’s more illustrious American League team was billed as the battle for the “Team of the ’90s” title, but it proved to be an anticlimactic end to the season. The Yankees swept the Braves to capture their third World Series in four seasons. Jones managed just three hits in the four games, including a home run off Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez in Game One.

After his MVP season, the Braves offered their star third baseman a six-year, $90 million contract extension, which briefly made him the highest-paid position player in baseball. Jones’s agent, Steve Hammond, took his time accepting and Chipper replaced him with his childhood friend, B.B. Abbott, and soon signed the deal. With his new contract in hand, he bought a 4,000-acre ranch in south Texas that he renamed the Double Dime, after the uniform number 10 that he and his father both wore.

Jones’s messy marriage with Karin ended that same offseason. By the time the 2000 season began, he had remarried to Sharon Logonov, a Florida native, in his parents’ front yard in Pierson. Their first son, Larry III, whom they called Trey, was born in June. Their second son, Shea, born in 2004, was named in part after the Mets’ home stadium, where Chipper always had such great success. His relationship with New York fans had once been hostile, but it evolved into something more like mutual respect after the tragic events of September 11, 2001, took an edge off the Braves-Mets rivalry. “I didn’t mean [my son’s name] to be a slap in the face to the fans of New York,” Jones said. “I enjoyed playing on that stage. Other than Atlanta, there’s nowhere else I wanted to play more than New York.”36

Following the 2001 season, GM John Schuerholz and team president Stan Kasten approached Jones about moving to left field so they could sign former All-Star third baseman Vinny Castilla. Jones was reluctant to switch positions, but he had played in the outfield before and agreed to move for the good of the team. Jones enjoyed a chance to get away from the pressure of the infield. “I used to spend so much mental preparation on defense, either working on it or worrying about it,” he said. “I’m sure it took away from my offense.”37

Castilla provided a solid option at third base but he re-signed with the Colorado Rockies as a free agent after just two seasons in Atlanta, turning over the position to Mark DeRosa. In 2003, the Braves signed Gary Sheffield to play right field. With perennial Gold Glove winner Andruw Jones in center field and Chipper Jones in left, they made for one of the most formidable outfields in baseball. With the two right-handed sluggers between him, Chipper was moved to the cleanup position instead of his customary No. 3 spot in the lineup. No matter where he played, he continued to produce at the plate, averaging 26 homers and 103 RBIs in his two full-time seasons as a left fielder.

With the Jones boys anchoring the lineup, and a rotating cast of starting pitchers — with Russ Ortiz, Mike Hampton, and Tim Hudson replacing the Big Three of Glavine, Maddux, and John Smoltz, now the closer — the Braves continued to dominate the NL East in the early 2000s. But they only made it out of the first round once, in 2001, and Atlanta players quickly grew tired of answering questions about October.

“People say we haven’t lived up to expectations because we’ve won only one World Series — but that’s one more than a lot of other teams have won,” Jones said. “We’re of the mind-set that if we keep giving ourselves opportunities in the postseason, one of these days it’ll bounce our way again.”38

In 2004, the Braves struggled out of the gate and it appeared as if their postseason streak might be in jeopardy. Jones strained his right hamstring chasing down a ball in left field in April and was out for three weeks. When he returned, his batting average spiraled down and he was hitting .214 at the All-Star break. With DeRosa struggling at third base and Jones still hobbled by nagging injuries, manager Bobby Cox decided to move his star back to his old position.

The switch might have saved the Braves’ season; they played .680 ball in the second half and finished with a 96-66 record. Jones batted a career-low .248, but belted 11 of his 30 home runs in August as the Braves overtook the Philadelphia Phillies for yet another NL East title. However, they bowed out again in the NLDS, this time to the Houston Astros.

Atlanta again got off to a slow start in 2005 and fell behind the Washington Nationals by the Fourth of July. But an infusion of young talent that included rookies Brian McCann and Jeff Francoeur — coined the “Baby Braves” — spurred a second-half run to the team’s 14th consecutive division title, a major-league record that may never be equaled. At age 33, Jones was the team’s elder statesman, contributing 21 home runs. But he missed more than 50 games after tearing a ligament in his left foot.

The Braves finally failed to reach the postseason for the first time in Jones’s career in 2006. Following the inaugural World Baseball Classic, in which he hit two home runs for the United States team, he batted .324 for the Braves, including a career-long 20-game hitting streak and his only three-homer game. But he was sidelined for another 52 games with nagging injuries, which would plague him for the rest of his career. He averaged just 122 games played during his final nine seasons. By the time he retired, he’d had six knee operations and survived the baseball grind “on a daily dose … of Percocet and a Red Bull.”39

After another solid season in 2007 — in which he hit .337, led the National League in OPS, and finished sixth in the MVP voting — Jones surprised everyone, including himself, with a white-hot start in 2008. He recorded hits in 18 of his first 19 games and kept his average over .400 for more than two months. When he hit his 400th career home run on June 5 against Florida Marlins right-hander Ricky Nolasco, his batting average stood at an astounding .418, inspiring talk that the 36-year-old could become the first player since Ted Williams in 1941 to surpass the .400 mark. Jones tried to downplay his chances and called the talk premature. “I don’t think anybody can do it,” he said.40

Two weeks later, his average fell below the .400 mark on June 19 in Texas, on the final game of a 10-day, four-city road trip. Still, he was hitting .376 with 18 home runs at the All-Star break. A shoulder injury sapped his power and he was limited to four home runs in the season’s last two months. Jones was reduced to a pinch-hitting role during the last two weeks and finished with a .364 average. He held off a late-season charge from St. Louis Cardinals slugger Albert Pujols to lead the NL in hitting for the first and only time.

“I don’t know if I would have won the batting title if I hadn’t had a sore shoulder,” he said. “If I’d been out there getting four, five at-bats a day, grinding on that shoulder, the numbers probably would have suffered.”41

Before the 2009 season, Jones signed a four-year, $61 million extension that would keep him in a Braves uniform for the rest of his career. “I’ve been good to the Braves, but they’ve been better to me,” he said. “They never even let me get to a free-agency year. The money I’ve made in the game is ridiculous, but I’d like to think it hasn’t changed me.”42

Jones played sparingly in the second World Baseball Classic that spring before leaving the United States team early with an oblique injury. His batting average dropped down to earth by 100 points to .264 and he grew so frustrated with his poor play that he met with Braves officials early in 2010 to discuss possible retirement plans. Bobby Cox, the only big-league manager he had ever played for, had already decided it would be his final season. With the Braves leading the NL East for most of the year and a postseason berth in sight, it felt like a fitting time to say goodbye after one last October run together.

Another devastating injury put an end to Jones’s thoughts of calling it a career. On August 10 at Houston, he charged in on a ground ball by the Astros’ Hunter Pence and blew out his left knee — shredding the same knee ligament he had torn 16 years earlier as a rookie in 1994. “In that instant, I knew retirement was out the window,” he said. “No way did I want to go out like that. I couldn’t retire limping off the field … for Bobby’s swan song.”43

Jones was forced to watch from the sidelines as the Braves lost a tight NL Division Series to the San Francisco Giants, ending Cox’s Hall of Fame managerial career. With his hand-picked successor, Fredi Gonzalez, taking the reins in the Braves’ dugout, Jones made it back on the field by Opening Day in 2011. That year, he passed Mickey Mantle with his 1,510th career RBI, placing him second only to Eddie Murray among all switch-hitters in baseball history. But Atlanta’s season ended on a sour note again when they blew an 8½-game lead in the wild-card standings in September and finished out of the postseason on the final day.

During spring training in 2012, the 40-year-old Jones decided to announce this would be his final season. His farewell tour got off to an ominous start: Hours before his emotional retirement press conference, he injured his knee again during a team stretching session and underwent surgery for a torn meniscus that forced him to miss Opening Day.44 But he hit a home run in his first game back, the first indelible moment in a year full of them.

During spring training in 2012, the 40-year-old Jones decided to announce this would be his final season. His farewell tour got off to an ominous start: Hours before his emotional retirement press conference, he injured his knee again during a team stretching session and underwent surgery for a torn meniscus that forced him to miss Opening Day.44 But he hit a home run in his first game back, the first indelible moment in a year full of them.

In every city Jones visited, opposing teams showered him with gifts: a Stetson cowboy hat from the Houston Astros; a customized surfboard from the San Diego Padres; a signed third-base bag from the Washington Nationals; and an original piece of art commemorating his career by his archrivals, the New York Mets, against whom he batted .309 with 49 home runs and 159 RBIs during his career.

His 468th and final home run was a memorable one: a three-run, walk-off blast against Phillies closer Jonathan Papelbon on September 2 at Turner Field, helping the Braves qualify for the postseason one last time, as a participant in the first NL Wild Card Game against the St. Louis Cardinals. In his final major-league appearance on October 5, Jones made a crucial error to start the Cardinals’ go-ahead rally in the fourth inning and went 1-for-5 in an elimination game that was marred by a controversial infield-fly ruling which cost the Braves an opportunity to tie the score.

In retirement, Jones has stayed away from baseball for the most part. He has hosted a series of hunting shows on television from his Texas ranch and he returns to Atlanta occasionally when the Braves ask him to offer hitting tips to the team’s young players and minor-league prospects. He also keeps busy raising his young family and coaching his sons’ sports teams. After three kids with Sharon, their marriage ended in 2012 and he remarried to model Taylor Higgins in 2015.

An all-around hitter who batted over .300 from both sides of the plate — the only switch-hitter in major-league history with more than 1,000 plate appearances to do so — Jones’s career was honored when he was elected to the Hall of Fame on the first ballot in 2018. He became the sixth member of the Braves’ dynasty to make it to Cooperstown, along with teammates Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz, manager Bobby Cox, and GM John Schuerholz.

“For us to have that little fraternity in a little piece of heaven up there in Cooperstown, New York, it’s something that we can and should be very proud of, because we did an awful lot of winning,” Jones said.45

Last revised: June 13, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Chipper Jones and Carroll Rogers Walton, Ballplayer (Dutton, 2017), 6. All page numbers are locations from the Kindle version of this book.

2 Jerry Crasnick, “One and done for Chipper Jones,” ESPN.com, March 22, 2012. Accessed online at http://www.espn.com/mlb/spring2012/story/_/id/7723234/chipper-jones-retire-2012-season on April 12, 2018.

3 Ballplayer, 6.

4 Ballplayer, 13-14.

5 Jack Wilkinson, “Chipper: The Natural,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 23, 1997, F6.

6 Including this author, who grew up near Atlanta and closely followed Jones’s career from beginning to end.

7 Ballplayer, 296-97.

8 Ibid.

9 Wilkinson, op. cit.

10 Ibid.

11 Jones switched to wide receiver at Bolles and led the state in receptions during his senior year, drawing attention from coaches Steve Spurrier at the University of Florida and Bobby Bowden at Florida State University. But he told them his future was in baseball.

12 Ibid.

13 Ballplayer, 32-34.

14 Cory McCartney, “Chipper Jones or Todd Van Poppel? Inside decision that led to Braves picking franchise icon,” Fox Sports, January 24, 2018. Accessed online at https://www.foxsports.com/south/story/chipper-jones-todd-van-poppel-012418 on February 10, 2018.

15 Ballplayer, 61.

16 Russ White, “Braves Choose Chipper,” Orlando Sentinel, June 5, 1990.

17 Ballplayer, 70-71, 89-90. Jones eventually settled on a 35-inch, 34-ounce Rawlings MS20 bat that he borrowed from Ron Gant; he used that model for his entire major-league career.

18 John Manuel, “Top 100 Prospects: Year by Year,” Baseball America, February 19, 2014, accessed online at https://www.baseballamerica.com/majors/top-100-prospects-year-by-year on February 10, 2018.

19 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, “Top 100 Teams,” MiLB.com, accessed online at http://www.milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=23 on February 10, 2018.

20 Ballplayer, 105.

21 Ballplayer, 125.

22 Ballplayer, 126.

23 Ballplayer, 128.

24 Ballplayer, 130.

25 Tim Kurkjian, “Pressure-Treated,” Sports Illustrated, October 16, 1995. Accessed online at https://www.si.com/vault/1995/10/16/207235/pressure-treated on April 12, 2018.

26 Ballplayer, 147.

27 I.J. Rosenberg, “Jones gets 4-year deal from Braves,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 17, 1996, F1.

28 Ballplayer, 149-50.

29 Ballplayer, 160.

30 Terence Moore, “Like it or not, Chipper must lead team now,” Atlanta-Journal Constitution, April 9, 1997, B1.

31 Ballplayer, 324.

32 Bill Zack, “Chipper Jones admits to fathering illegitimate child,” Savannah Morning News, October 22, 1998, accessed online at http://savannahnow.com/stories/102298/SPTchipper.html on February 19, 2018.

33 John Romano, “Braves-Mets: War of the Words,” Tampa Bay Times, October 12, 1999, 10C.

34 Tampa Tribune, October 23, 1999, 4.

35 Carroll Rogers, “Braves dim Mets’ playoff chances,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 1, 1999, D1.

36 Ballplayer, 248-49.

37 Guy Curtright, “Switch to left all right,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 31, 2002, P5.

38 “Chipper Jones,” Sports Illustrated, October 3, 2005. Accessed online at https://www.si.com/vault/2005/10/03/8357601/chipper-jones on April 12, 2018.

39 Ballplayer, 315.

40 Associated Press, “Chipper: .400 and holding,” June 8, 2008.

41 Ballplayer, 307.

42 Chipper Jones, “Bottom of the 19th: The Walk-off,” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 2012. Accessed online at https://www.si.com/vault/2012/09/17/106233934/bottom-of-the-19th-the-walkoff on April 12, 2018.

43 Ballplayer, 310-11.

44 Jayson Stark, “Chipper Jones to have knee surgery,” ESPN.com, March 24, 2012. Accessed online at http://www.espn.com/mlb/spring2012/story/_/id/7731316/2012-spring-training-chipper-jones-arthroscopic-surgery-torn-knee-meniscus on April 16, 2018.

45 Mark Bowman, “Head of the Class: Chipper elected to Hall,” MLB.com, January 24, 2018. Accessed online at https://www.mlb.com/news/chipper-jones-elected-to-baseball-hall-of-fame/c-265267272 on April 16, 2018.

Full Name

Larry Wayne Jones

Born

April 24, 1972 at DeLand, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.