The Babe Comes North

This article was written by David McDonald

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

“Don’t tell me about Ruth; I’ve seen what he did to people. … I’ve seen them: kids, men, women, worshipers all, hoping to get his famous name on a torn, dirty piece of paper, or hoping to get a grunt of recognition when they said, ‘H’ya, Babe.’ He never let them down; not once! He was the greatest crowd pleaser of them all.” – Waite Hoyt 1

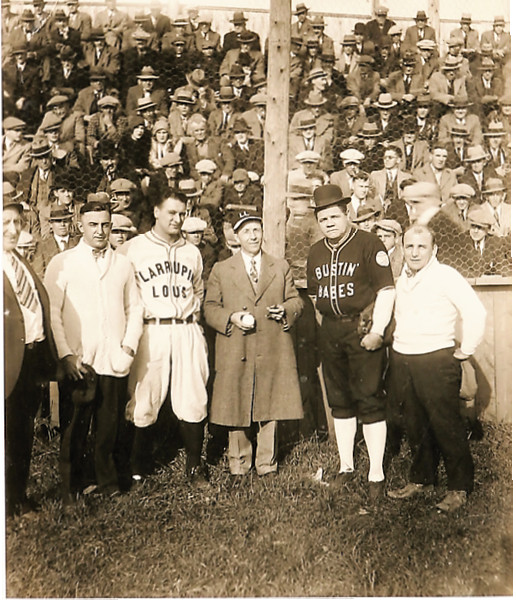

Parc Dupuis, Hull, Quebec. October 15, 1928. Left to right: unidentified in striped tie; Peter St. Pierre, umpire; Lou Gehrig; Hull mayor Théo Lambert (wearing Lou’s cap); Babe Ruth (with Lambert’s size 7 1/8 bowler perched precariously on his prodigious melon); Gene Coderre (umpire). (From Lambert Estate. Courtesy of Heritage Auctions)

Just six days after winning the 1928 World Series, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig stepped off a train at Union Station in Ottawa, Ontario, the Canadian capital. It was a Monday noontime in mid-October, and some 500 fans, many of them boys conspicuously absent from school, milled expectantly in the concourse.

Suddenly the two greatest players on the greatest team in baseball came through the gate. For all the attention he attracted, the younger one, a handsome, Columbia University-educated 25-year-old, who would one day screen-test for the role of Tarzan, might have been a railway clerk on his way to lunch. Every eye in the place was locked on his companion, a beaming, pug-faced 33-year-old in a brown suit, brown overcoat, and a brown felt hat.

The crowd engulfed him, slapping him on the back, yelling “Hurrah for The Babe.”2 Despite his 6-feet-2-inches and 217 pounds, Ruth moved with a surprising nimbleness, hailing knots of kids with a scattershot “Howdy, bud,” as he made his way through the hall.3 Breaking stride for an instant, he centered out one small boy on the fringes of the mob for a cheery “Hello.” The boy went popeyed and almost fell over.4 The biggest kid on the continent had spoken to him.

One reporter found Ruth “far from the phlegmatic type many imagine. … He had a cheery word for everybody and, while he is perhaps one of the most pestered people in the world, he stands the often trying adulation of the sport mob with great patience and takes zest in everything and everybody, particularly the youngsters.”5 In fact, one of the first things Ruth had done when he arrived was to dash off a wire to the superintendent of the Ottawa Boys’ Club, with his best wishes for the organization.

The Murderers’ Row Yankees, hit hard by illness and injury, had won 13 fewer games in 1928 than they had the previous season. Ruth, hobbled by a charley horse and other ailments, had seen his average dip from .356 to .323, and his home runs from an iconic 60 to a mere league-leading 54. Gehrig’s average had held steady, but his home-run total had plummeted, from 47 to 27.

It was just enough to carry the Yankees to their third straight American League pennant, by 2½ games over the Philadelphia Athletics. In the Series, they would be up against the St. Louis Cardinals, a team featuring six future Hall of Fame players and a Hall of Fame manager.

It was no contest. Ruth batted .625 (10-for-16), with three home runs, all coming in the fourth and final game. “The able Ruth, heralded as a cripple, pounded the crack St. Louis hurlers as if they were but Class ‘C’ pitchers in a bad slump,” the Ottawa Journal reported.6 Gehrig, for his part, batted .545 with 4 home runs and 9 runs batted in. Sweep, Yankees. Babe and Lou each pocketed a winner’s share of $5,531.97. Now it was time to make some real dough.

Star players could make as much or more with a postseason barnstorming tour as they could in an entire major-league season. Ruth, for one, had barnstormed practically every fall since 1916, when he was still a member of the Boston Red Sox. Given his prodigious appetite for flivvers, floozies, stogies, hooch, and weenies, the postseason appearances had become something of a financial necessity.

In 1927 Ruth had recruited rising superstar Gehrig and embarked on a 21-game “Bustin’ Babes and Larrupin’ Lous” odyssey, from Providence, Rhode Island, to San Diego, California. Playing with and against mostly amateur and semiprofessional squads, the pair drew some 220,000 fans. Ruth netted about $70,000 from the tour, the equivalent of his annual Yankees’ salary. Gehrig received a flat $10,000, which was $2,000 more than he’d earned during a regular season in which he had batted .373 and driven in 173 runs.

The 1928 World Series wrapped up on October 9. Five days later, Ruth and Gehrig kicked off their second Bustin’ Babes and Larrupin’ Lous tour in Montreal, where they lined up with Ahuntsic, champion of the racially integrated, semipro Ligue de la Cité (City League), against Chappie Johnson’s All-Stars,77 an all-black team from the same circuit. Before the game, they staged a home-run derby, swatting pitch after pitch out of the park to the delight of a crowd of between 14,000 and 16,000.

The game ended – as these games frequently did – with the fans flooding onto the field in the bottom of the eighth to celebrate a Gehrig home run that gave Ahuntsic an 8-6 lead. Ruth, who had last pitched in the majors in 1920, tossed the final three innings for the win, but at the plate managed only a pair of singles and a walk.

Arriving in Ottawa the next day, Babe and Lou repaired to a first-floor suite at the landmark Château Laurier hotel, just across the Rideau Canal from Canada’s Parliament Buildings. Ruth invited local newsmen to hang out as he and Gehrig prepared for their game later that afternoon in Hull, Quebec, the city on the north side of the Ottawa River opposite the capital.

Inevitably, having landed in a political town, Babe was pressed for his thoughts on the upcoming US presidential election. He was an Al Smith supporter, he said, referring to the anti-Prohibitionist Democratic governor of New York, but conceded that Smith had “a tough fight ahead of him.”8

Gehrig’s political opinions, if any, went unrecorded.

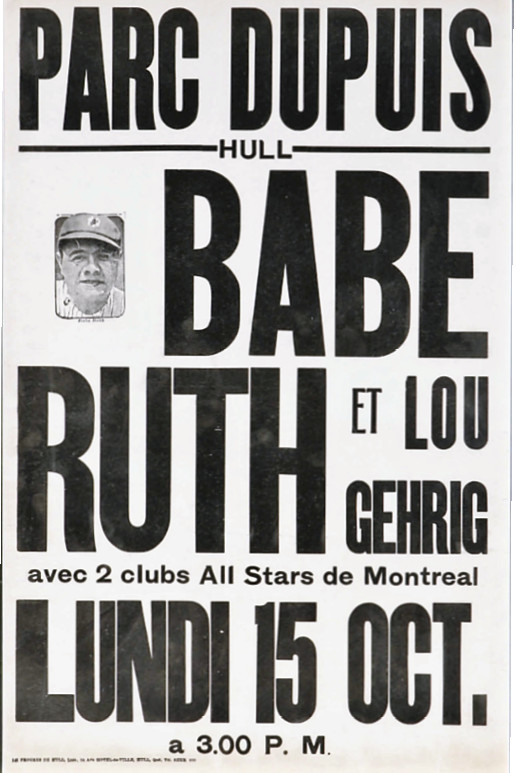

Babe in Hull, Quebec, Broadside, October 1928. From the estate of former Hull mayor Théo Lambert. (Courtesy of Heritage Auctions)

“I know that as long as I was following Ruth to the plate I could have stood on my head and no one would have known the difference.” – Lou Gehrig9

While the reticent Gehrig did his best to blend in with the wallpaper, The Babe held court. “Tell the boys we are both glad to be here, even for such a short visit,” he said, “and at Dupuis Park this afternoon we will try and provide our share of the entertainment.”10

Asked how he was feeling, Ruth said, “I bet I can’t even throw a ball today, that arm of mine is so sore.”11 Was he going to pitch in Hull? “You bet your life I’m not,” he guffawed, adding that he had also signed 18 dozen baseballs as part of the Montreal appearance.12

“Babe Ready for Hull Swatfest,”13 reported the Ottawa Citizen, while the Ottawa Journal colorfully stated the obvious: “The thousands who are likely to crowd the park will want to see Lou and Babe whang the apple over the car tracks.”14

For a 3 o’clock game on a Monday afternoon in the middle of October, more than 3,000 spectators paid a dollar apiece – 50 cents for kids – to see Ruth, in his black Bustin’ Babes uniform (which, one reporter quipped, “showed his figure to advantage”15) and Gehrig, in his Larrupin’ Lous whites, do some heavy whanging. Ahuntsic and an integrated all-star team from the Montreal City League made up the supporting cast. The promoters had brought five dozen baseballs so there would be a ready supply for the pregame home-run exhibition and autograph session.

On this day, Ruth and Gehrig swapped their usual positions. Babe shifted to first base to give his sore wing a rest, a move that would also give him the chance to engage in nonstop banter with the fans. Lou started in left field, then came in to pitch the last two innings.

A swatfest it wasn’t. Neither slugger could make solid contact against the All-Stars’ pitcher, from the Guybourg club of the Montreal City League. He was identified in the box scores as Guillaume, but his real name was Ralph Williams, nicknamed Bill. One of the top hurlers in the province, Williams was a 35-year-old right-hander with a baffling array of deliveries – overhand, side-arm, underhand. Guillaume was the gallicized nom de guerre he assumed when he played for francophone teams.16

After the match, there were grumblings from fans about Guillaume’s perceived failure, whether dictated by nervousness or competitive pride, to groove some of his offerings to the Yankee sluggers. For eight innings, he held Babe and Lou not just homerless but hitless. One reporter would liken the disappointing spectacle to “a performance of Hamlet without the Dane.”17

The All-Stars, bolstered by some local athletic royalty – future Hockey Hall of Famers Frankie Boucher, star center of the Stanley Cup champion New York Rangers, and his brother George, an Ottawa Senators defenseman – led 1-0. George belted a double off Gehrig and robbed Ruth with a one-handed stab up against the center-field scoreboard.

Ahuntsic tied the game in the seventh, when Gehrig reached base on an infield error and later scored. Then in the eighth, Ruth finally got hold of one, doubling to drive in two and break the 1-1 tie. Gehrig followed with a fly out, stranding Babe at second. With that the kids in the stands, unable to restrain themselves any longer, poured onto the field, bringing the game to an early end.

“Over the fence they came in hundreds,” the Citizen reported, and The Babe was engulfed by “a milling, shouting, worshipping mob of youngsters who clamored for handshakes, autographs and what have you in general.”18 The what-have-yous included Ruth’s Bustin’ Babes cap and both sluggers’ bats, which were borne off like religious relics.

Babe and Lou eventually managed to jostle their way to the parking lot. They drove away, a swarm of kids pursuing their car through the streets of Hull.

Back in Ottawa, they boarded an 11 P.M. train at Union Station. Next stop: Buffalo.

DAVID McDONALD is a writer, filmmaker and broadcaster who grew up watching Rocky Nelson, Sam Jethroe, and Mike Goliat at Maple Leaf Stadium in Toronto. He lives in Ottawa, Ontario.

Notes

1 John Tullius, I’d Rather Be a Yankee: An Oral History of America’s Most Loved and Most Hated Baseball Team (New York: Macmillan, 1986), 40.

2 “Big Crowd Welcomes Ruth and Gehrig to Ottawa; Babe Is for Al; Monarch of the Diamond Is in Ottawa with His Larruping Team-Mate; May Go Fishing Up the Gatineau,” Ottawa Journal, October 15, 1928.

3 “Babe Ready for Hull Swatfest,” Ottawa Citizen, October 15, 1928.

4 Ottawa Journal, October 15, 1928.

5 “Home Run Twins Perform Here Monday; Great Babe Ruth and Gehrig, Heroes of 1928 World Series, to Be in Action (at) Dupuis Park; Stars of New York Yankees’ Triumph Over St. Louis Cardinals in World Series Will Exhibit Their Prowess with the Bat Before Ottawa and Hull Fans, Will Line Up with Two Teams Selected from Montreal Semi-Pro Ranks. Yankee Pair Set Up String of Records with Home Run Drives Against Cardinals,” Ottawa Citizen, October 12, 1928.

6 Salt Lake City Tribune, October 10, 1928.

7 7 A.k.a. the Chappies, owned and managed by former Negro Leagues star George “Chappie” Johnson Jr., a native of Bellaire, Ohio. The Chappies played in the Montreal City League in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s.

8 Ottawa Journal, October 15, 1928. Rarely reluctant to share his political opinions, Ruth nevertheless failed to cast a ballot in 1928 or in other presidential election until 1944.

9 Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Players (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1953), 99.

10 Ottawa Citizen, October 15, 1928.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Baz O’Meara, “Sport Facts and Fancies,” Ottawa Journal, October 15, 1928.

15 “Ruth and Gehrig Failed to Hammer Out Keenly Awaited Circuit Wallops, Disappoint Three Thousand Fans; Young Admirers Rush Twain Off Field and Break Up Game – Ruth Good Showman – Geo. Boucher Stars with Circus Catch of Ruth’s Hit,” Ottawa Journal, October 16, 1928.

16 Bert Williams, 92-year-old son of Ralph Williams, telephone interview with author., December 17, 2009. Ralph Williams, a.k.a Guillaume, once told his son that facing Ruth and Gehrig “was the best thing he ever did.”

17 Ottawa Journal, October 16, 1928.

18 “Ruth and Gehrig Thrill Crowd in Exhibition Game at Dupuis; Home Run Kings Play Before Huge Throng on Hull Diamond. Neither Lou nor Babe Blast Any Long Balls Out of the Park During Contest, but Show Prowess at Long Distance Hitting in Batting Practice. Ruth’s Double Wins Game for Ahuntsic Team. Youngsters Terminate Game in 8th, Nearly Mobbing Babe and Lou,” Ottawa Citizen, October 16, 1928.