The Bats … They Keep Changing!

This article was written by Stephen Bratkovich

This article was published in Fall 2018 Baseball Research Journal

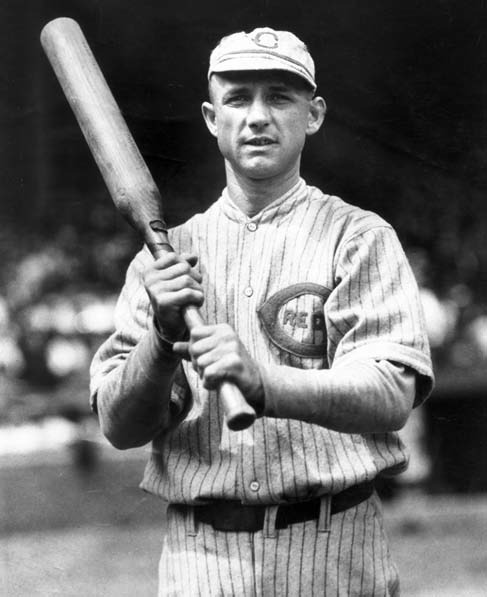

Heinie Groh of the Cincinnati Reds had one of the most distinctive bats in baseball history, a “bottle bat” which had about a 17-inch barrel that tapered sharply to a thin handle. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Introduction

Over the centuries, baseball bat shapes have undergone all kinds of contortions: Bat diameters have expanded and contracted and lengths have varied. Even bat wood species have transitioned from hickory and the traditional ash to maple, which dominates today in major-league baseball (MLB).

As baseball and its people have changed, the use of wood to make bats has not. In fact, at the highest level of baseball — and its blood-brother cricket — the object used to strike the ball is fashioned from a tree.1

The book Baseball as America, issued jointly by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum and the National Geographic Society, argues that professional baseball has stuck with a wooden bat for numerous reasons, including safety, competitiveness, and the preservation of tradition.2 This article focuses on MLB bats and the renewable material called wood.

Sizes, Shapes, and Species of Wood

During the mid-1840s, when the Knickerbockers were playing the game under their rules, all players were responsible for their own bat. This “bring your own bat” to the game resulted in many different sizes, shapes, and species of wood.3

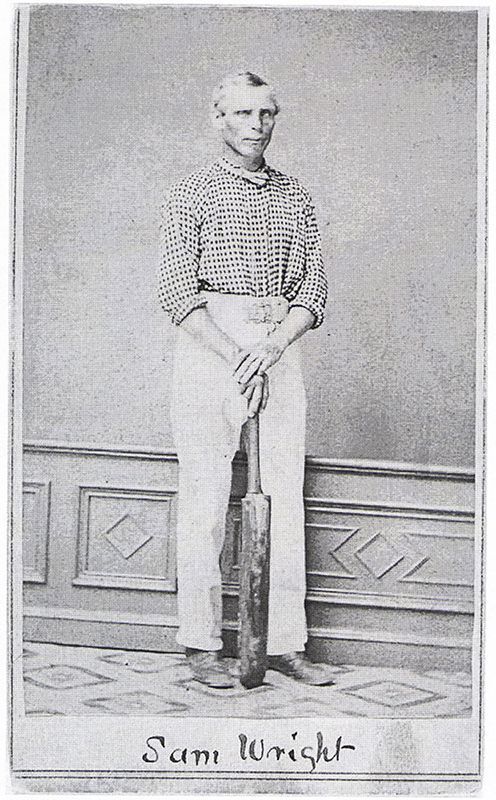

The earliest bats were quite primitive, akin more to a “club” than what we think of as a bat in the twenty-first century. Some bats came from tree limbs and some began their life as ax handles. Early bats were often flat — like cricket bats — and most were handmade from various trees such as sycamore, cherry, spruce, chestnut, poplar, and basswood. For a short time, the cricket-favored willow was the preferred choice.4 Ash, maple, and pine were also favorite woods of batters in the earliest days of the game.5

By trial and error, ash and hickory emerged as the most popular woods for bat-making in the 1870s and ’80s.6 Even though hickory is a very dense, strong wood, ash eventually held the advantage since it has an unusually high strength-to-weight ratio. Physicist Robert Adair, in his book The Physics of Baseball, wrote, “Ash was celebrated in medieval times as the only proper wood from which to construct the lances of knights-errant; an ash lance was light enough to carry and wield and strong enough to impale the opposition.”7 Roger Maris used a 33-ounce ash bat to hit 61 home runs in one season; a hickory bat of the same dimensions would weigh about 42 ounces.8

In 1884, the year the modern fountain pen was invented, the first Louisville-Kentucky-manufactured bat was made.9 As legend has it, John “Bud” Hillerich, shaped a baseball bat on a lathe out of white ash for the American Association’s Louisville slugger, Pete Browning. Browning, who had a .341 career batting average, had broken his favorite bat earlier in the day. Hillerich spoke with Browning after the game, promising to make the slugger a new bat in his father’s shop. Browning went 3-for-3 the next day with Hillerich’s bat. This simple event gave birth to a new Hillerich industry: baseball bat manufacturing.10

From the beginning, the Hillerich firm, later to become Hillerich & Bradsby, tried different tree species for bat-making. Eventually, the company settled on white ash (northern range of species) as the best.11 For roughly a century, white ash (Fraxinus americana) dominated the bat market for all manufacturers and players. Within the first few minutes of Ken Burns’s (originally) 18-hour documentary series Baseball, narrator John Chancellor intones, “The bat is made of turned ash, less than 42 inches long, not more than 2¾ inches in diameter.”12

But players and entrepreneurs kept tinkering with bat dimensions and types of wood. In the late 1880s, many bat manufacturers were seeking new sources of raw material. The durable wood used for wagon tongues — which connects a wagon’s wheel base to the draft animals — was considered fine material, and as Americans became less dependent on the horse and buggy, more of them were becoming available.13 Even newspaper ads advertised for wagon-tongue wood. As an example, A.G. Spalding & Brothers purchased wagon tongues from the general population with the specific intent of “turning [shaping the tongues] into bats.” In one ad, Spalding noted that he wanted to buy 100,000 old wagon tongues for use in his company’s Wagon Tongue Brand of baseball bats. Spalding warned that he only wanted “straight grained, well-seasoned, second growth ash.”14

At least one historian speculates that an early form of European baseball might not have included a bat at all. David Block, in the Our Game blog, writes, “The question of when a bat was first introduced to the pastime remains a mystery. It is certainly possible, if not probable, that, at its outset, the game of baseball [in Europe] did not employ a bat, and that a bare hand was used to strike the pitched ball.” Block muses that the difference in baseball in Europe and the United States might be due to different social underpinnings. In England, baseball was played primarily by girls and young women, whereas in America, baseball became a sport for boys and men. The American version of the game — faster, rougher, and on a larger scale — might have accompanied the adoption of the bat perhaps perceived in England as too un-lady-like.15

Regardless of when a bat was first introduced in Europe, the vast Atlantic Ocean did not negate the appeal of baseball in the New World. The sport grew, and with the expanding interest in baseball came many modifications in bat dimensions. While players were making the switch to wagon-tongue wood, another revelation appeared to them: A ball could be hit much more solidly with a round bat. This observation led to the adoption of a round bat as the standard that exists to this day.

David Magee and Philip Shirley explain in their book Sweet Spot that the design of a bat, including a round barrel, was not “a given” in the early days of the game:

Some players used square bats for bunting, while others played with square-handled bats. Others preferred thick handles, resulting in a bat that was nearly uniform in width from handle to barrel. Players selected their bat of choice often based on little more than a hunch; if they happened to connect solidly in a game with one, they often used that one bat until someone convinced them otherwise. The bat, in other words, was still evolving by trial and error.16 Henry “Heinie” Groh spent 16 seasons in the major leagues, mostly with the New York Giants and Cincinnati Reds. He debuted in 1912 with the Giants and wrapped up his career with a one-year stint in Pittsburgh. Groh posted a lifetime batting average of .292 and hit .474 in the 1922 World Series against the New York Yankees. He batted over .300 four times in a five-year span and was a part of five pennant winners, including two World Series championships. However, Groh is best remembered not for these or other accomplishments but for his famed “bottle bat,” which had about a 17-inch barrel that tapered sharply to a thin, roughly 17-inch handle. Groh had small hands, and because thin handles were not commonly made in the early twentieth century, Groh devised a bat he could get his fingers around. The advantage of Groh’s long barrel gave him a greater hitting zone. Although Groh’s unique bat didn’t catch on with many of his contemporaries, the “bottle bat” worked for him.17

As the twentieth century gave way to the twenty-first, more and more major-league players switched to hard (sugar) maple. When the 2017 big-league season began, about 75 percent of major-league batters swung maple (Acer saccharum). Ash bats had dramatically fallen to 10-15 percent of the big-league market.18 Also, the number of firms supplying bats to MLB skyrocketed from the days of Pete Browning and Heinie Groh to 32 different licensed manufacturers for the 2017 season.19

Samuel Wright, the resident professional for the St. George Cricket Club in New York City, was the father of Baseball Hall of Famers George and Harry Wright. Early baseball bats were often flat, similar to the cricket bat shown here. (COURTESY OF JOHN THORN)

Rules

As the game spread in America, more and more men were organized into clubs, or teams, for the purpose of playing baseball. In 1857, clubs gathered in lower Manhattan to discuss rules and competition between one another (a year later a permanent body was formed: the National Association of Base Ball Players).20 One of the rules adopted stated that a bat “must be round, and must not exceed two and half inches in diameter in the thickest part. It must be made of wood, and may be of any length to suit the striker.”21 Prior to this bat rule, a player could lug a piano leg to the plate if he wished.

However, flat bats were legalized by the National League in 1885, and became ideal for bunting.22 In 1893, the 1857 rule requiring a round bat was reinstated.23 Soft woods (like pine) and bats that were sawed off at the end were banned as well.24

In 1868, a rule setting the maximum length at 40 inches was established. A year later the length was extended to 42 inches. In 1895, the National League allowed the bat diameter to expand to two and three-quarters inches.25 As of the 2018 MLB season, the maximum length remains at 42 inches and the diameter is capped at 2.61 inches.26

A bat altered by scooping out an ounce or so of wood from the end of the barrel is known as a cupped bat. Cupped bats were originally manufactured in the late 1930s by the Hanna Manufacturing Company of Athens, Georgia, but weren’t legalized in MLB until 1975. Cupping results in a lighter bat and shifts the center of gravity farther down the barrel.27 Jose Cardenal signed the first contract with Louisville Slugger for a cupped bat. Because the handle was not too thin and the barrel not too heavy, Cardenal said, “It’s just a very well-balanced bat. You put it in your hands and you can feel it.”28 Many major leaguers in the twenty-first century use a cupped bat. The 2018 MLB rule book limits the “cup” to one and one-quarter inches in depth and between one and two inches in diameter.29

The bat handle rules can be traced all the way back to the late 1800s, according to baseball historian John Thorn. In 1885, a rule was put into place by the National League that limited twine on the handle end of the bat to 18 inches. The next year, the rule was modified to account for gritty stuff like rosin and dirt. Like the previous year’s rule, 18 inches was the maximum length these substances could be applied to the bat handle.30

In 1976, the rule was updated. Team owners had discovered that pine tar on bat handles was the leading culprit for the increasing number of soiled baseballs being thrown out of play by umpires. Led by Calvin Griffith of the Minnesota Twins (formerly the Washington Senators), the owners, with an eye on saving money, pushed for a more specific rule that mentioned the sticky substance. According to Fillip Bondy’s book The Pine Tar Game, the updated rule stated:

The bat handle, for not more than eighteen inches from its end, may be covered or treated with any material or substance to improve the grip. Any such material, including pine tar, which extends past the eighteen inch limitation, in the umpire’s judgment, shall cause the bat to be removed from the game. No such material shall improve the reaction or distance factor of the bat.31 The new language was tested on July 24, 1983, when George Brett of the Kansas City Royals connected with a two-run homer off Goose Gossage of the Yankees in the top of the ninth inning with two out and New York clinging to a one-run lead. Yankees manager Billy Martin popped out of the dugout and insisted to the umpires that Brett had used an illegal bat, since the pine tar on the handle extended well beyond 18 inches. After much discussion and arguing, including screaming and cursing by both teams, the umpires agreed with Martin, and Brett was called out, nullifying the home run that had put the Royals ahead. Several days later, after a lengthy review, American League President Lee MacPhail sided with Brett and the Royals and called for a make-up of the game’s conclusion, replayed from the point of Brett’s home run. Since the 1976 rule (6.06) said nothing about a player using a bat like Brett’s being called out, the home run was ruled legal.32

After that famous “Pine Tar Game,” a note was added to the rule book. It states that if an umpire discovers a bat that has any material or substance beyond 18 inches from its end after it has been used in play, the batter will not be ruled out or ejected from the game . Furthermore, the rule book states, that action on the field will not be nullified and protests will not be allowed (a new numbering system was implemented in 2015; for the 2018 season, the updated rule is 1.10).33

Bats in MLB

The first baseball bats in America, even before the formation of the Knickerbockers, were heavy, thick, and barely tapered. To a baker, as well as to baseball players and fans, the bats looked like long rolling pins.34

Deadball Era (prior to 1920)

This era was called “deadball” primarily because of the baseball. According to Lawrence Ritter:

The game was played differently then simply because the ball was different. It looked just like today’s baseball, but when it was hit, no matter how hard, it did not carry long distances. . . . With such a dead ball, batters didn’t swing with all their might. . . . They practiced bunting and place hitting . . . they punch[ed] line drives . . . and slapp[ed] hard ground balls.35

Also, the extremely heavy bats favored in the first decade of the twentieth century were made primarily of hickory, a very dense wood.36 However, some players used ash as their lumber of choice since ash had the reputation as the best wood for a baseball bat.

Wee Willie Keeler, standing only 5’4” and weighing a mere 140 pounds, used a bat characteristic of the time regarding weight. Keeler’s bat often weighed 46 ounces (although because of his small stature, the length was a Little League size of 30 inches). In 1897, he batted .424 and set a National League record with a 45-game hitting streak. (According to the SABR BioProject site, Keeler’s streak stretched from the last game in 1896 through 44 games to begin the 1897 season.) Keeler, who batted .341 between 1892 and 1910, espoused the hitting philosophy of the day: “Hit ’em where they ain’t.”37

Another MLB star who exemplified the Deadball Era of “hit ’em where they ain’t” was Ty Cobb, the 11-time American League batting champion and all-time leader in batting average (.366). As an 11- year-old, one of Cobb’s first bats was crafted for him with scrap wood by his next-door neighbor, a coffin maker. Supposedly, the wood used was black mountain ash.38 Since local names for different trees can vary, and since the only tree in the twenty-first century called a “mountain ash” is a smallish ornamental tree that isn’t really an ash at all, the guess is that Cobb’s “coffin-wood” bat was actually white ash (or perhaps green ash), native to his home state of Georgia. Regardless, Cobb brought his “lucky” bat in a cloth bag to the big leagues in 1905.39

In the majors, Cobb wielded a 34½-inch bat that weighed a hefty 40 ounces (although he used a lighter bat near the end of his career). He spread his hands a few inches apart on the handle, which made the heavy bat easier to control as well as providing stability to slap at the ball. Cobb explained in 1910, as quoted in the Charles Leerhsen book Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty, “The great hitters of our time grab their batting sticks a foot or more from the handle and, instead of swinging, aim to meet the ball flush. . . . I stick to the sure system of just meeting the ball with a half-way grip.”40

In the early twentieth century, Cobb wasn’t the only superstar to swing a heavy bat or use a “split-grip” at the plate. Honus Wagner, who won eight National League batting average titles with the Pittsburgh Pirates between 1900 and 1911, also held his hands apart on the handle and wielded a bat that weighed up to 38 ounces. Although Wagner’s bat was two ounces lighter than Cobb’s, his “stick” was a tad longer, measuring 35 inches in length.41

Another Hall of Famer, Edd Roush, who started his 18-year big-league career in 1913, explained that his 48-ounce hickory bat with a thick handle was important to his success.42 As quoted in Good Wood, Roush said, “I only take a half swing at the ball, and the weight of the bat rather than my swing is what drives it.”43

Rogers Hornsby was one of the first major-league players to use a thin-handled bat, which he thought helped him swing the bat head through the hitting zone more quickly. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Live-ball Era (approximately 1920 to 1940)

The Deadball Era ended for a host of reasons, including the elimination of the spitball (1920), the use of more (and cleaner) baseballs per game (1921),))), and the center of the baseball featuring a rubber-coated cork core instead of a pure rubber core (introduced in 1910).44 Not only was the heavy hickory bat gradually replaced by the lighter ash as the preferred tree species for MLB bats, but two other major shifts occurred.

First, a trend of tapered bat handles began. Rogers Hornsby is often overlooked as the player who popularized the practice of using a thin-handled bat. Hornsby realized that a thin handle enabled him to get the bat head through the hitting zone more quickly. He hit 36 home runs in his first five full seasons (1916-20) but changed his ways in the roaring ’20s. Hornsby ripped 21 homers in 1921 while also leading the National League in batting average (.397), hits (235), doubles (44), triples (18), runs (131), and RBIs (126). He followed up that spectacular season by clubbing a league leading 42 home runs in 1922 while batting .401 and driving in 152 runs. For six consecutive seasons starting in 1920, Hornsby led his league in batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging average.45 With Hornsby’s success at the plate, coupled with the rise of a certain other superstar, the trend toward tapered handles had begun in earnest.

Although Babe Ruth swung a heavy bat (40 to 47 ounces), especially in his early playing days, he realized that a thin handle (patterned after Hornsby) and big barrel gave him more of an opportunity to swing from his heels.46 (Ruth sometimes used bats heavier than 50 ounces, but mostly in spring training).47 Since Ruth was paid to hit home runs rather than advance runners one base at a time, he wanted a large barrel on his bat so he could clobber the “lively” ball. He once said, “There’s nothing that feels as sweet as a good, solid smash.”48 A thick bat handle — favored by many Deadball Era stars — did little for what Ruth wanted to accomplish at the plate.

The 714th and last home run Ruth ever hit was in 1935 with the Boston Braves, when he was experimenting with, in his mind, a lightweight bat, 36 ounces. Ruth’s blast was the first time a baseball cleared the right field roof at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field.49

Author Charles Leerhsen pointed out major differences between slugger Ruth and deadball place-hitter Cobb:

[Ruth] held [the] bat very differently than Cobb gripped his much thicker club — all the way down at the knob end — and swung it differently, too, with a decisive uppercut motion, and with such force that if his spikes stuck in the clay around home plate, he could, and sometimes did, wrench his back. When he made contact with . . . the “jackrabbit ball,” the results were electrifying.50 Some deadball stars frowned on the home run since the game they played depended on place hitting, advancing the runner, bunting, and speed. It’s important to recognize that baseball started out as a meadows game. Once it was realized that people would dole out money to watch the game, fences were erected to eliminate non-payers. To preserve baseball’s character, it was not uncommon to build the fences far away to keep them out of play. Consequently, batters — with the encouragement of coaches, managers, and owners — attempted to hit line drives, not out-of-the-park home runs.51

To shed a perspective on distant outfield fences, consider the original Braves Field in Boston. The left-field foul line was an incredible 402.5 feet from home plate, and the right-field line measured 375 feet (though some books and websites list the ballpark’s opening-day distance between 369 and 402 feet). Center field measured a whopping 461 feet, with right-center a gigantic 542 feet from home plate. A 10-foot wall rimmed the park. When Cobb saw the new Braves Field in 1915, he exclaimed, “Nobody will ever hit a baseball out of this park.” Cobb’s prediction was a bit sarcastic but it did take a batter two years before a home run sailed over the wall.52

Cobb was one of the deadball players who initially believed Ruth’s swing-for-the-fences mentality was the wrong way to play baseball.53 Even many managers, writers, and fans argued that Ruth’s bombastic show lessened the game and wasn’t effective baseball strategy. They preferred the more chess-like game played since the late 1800s.54 However, Cobb finally relented and said Ruth’s style was a legitimate, alternative, and crowd-pleasing way to play the game and should be encouraged.55 Consequently, and with the blessings of two of the all-time greats of the game (Ruth and Cobb), thinner handled bats changed the game for the next century.

Ted Williams used a lighter bat than most of his contemporaries, which generated far more speed in his swing than a heavier bat. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Bat-Speed Era (approximately 1940 to 2000)

Another milestone in the history of MLB bats occurred when Ted Williams came to the majors. Williams, a rookie in 1939, batted .327, smacked 31 home runs and led the American league in RBIs with 145.56 Williams said many times that hitting a baseball properly is the most difficult thing to do in all of sports, and succeeding three times out of 10 is a great performance.57 If so, Williams did very well at the task. He posted a lifetime .344 batting average in a career that spanned from 1939 to 1960.58

Williams swung a bat crafted from ash, the favored wood of that era. His bat weighed 33-34 ounces for much of his career, a light bat compared to Ruth, Cobb, and most players in the early days of baseball.59 The bat length for Williams was 35 inches, comparable to the length of many deadball stars.60 However, the “secret” for Williams was the speed he generated with a light bat.

Williams’ theory was that a lighter bat could still produce plenty of power because a hitter generates more bat speed. One story that Williams told in his own book, My Turn At Bat, is that as a minor-leaguer in 1938, he was feeling tired near the end of the season. By chance, Williams picked up a teammates’ light bat and liked the feel of it. Williams wrote, “It had a bigger barrel than mine, but lighter by two ounces at least.” Williams got the approval of his teammate to use the bat that night with the bases loaded. Against a left-handed pitcher, Williams wrote, “I got behind two strikes. I choked up on the bat, thinking that I would just try to meet the ball. . . . The pitch was low and away, just on the corner of the plate. Unnh. I give this bat a little flip and gee, the ball flew over the center-field fence.” A 410-foot grand slam and Williams’ theory of a light bat was solidified.61 As the old saying goes: The rest is history.

Williams was meticulous (some might say paranoid) about the weight of his bats. He urged the Red Sox to install a scale in the clubhouse so he could precisely weigh his bats, saving a trip to the post office.62 One time, as legend has it, J.A. Hillerich Jr., laid out six bats on a motel bed in front of Williams. Hillerich then asked Williams to close his eyes and pick out the heavy bat, which was only a half-ounce heavier than the other five, a difference likely imperceptible to most humans, but not to the Splendid Splinter. Williams wrote in My Turn At Bat, “I picked it out [the heavy bat] twice in a row.”63

Williams was meticulous about more than just the weight of his bats. He once got a new shipment of bats from the Hillerich & Bradsby factory. Displeased with the handles, he returned the set of Louisville Sluggers with a short note that said, “Grip doesn’t feel just right.” Upon receipt at Hillerich & Bradsby, employees used calipers to measure the bat handles. Williams was right: The handles were five thousandths of an inch thinner than he had ordered!64

Ted Williams was a perfectionist as a hitter beyond just the “feel,” heft, and end-to-end distance of his bats. As Magee and Shirley wrote in their book, Sweet Spot:

He wanted the very best bat, from the best wood, with the perfect weight and length. He wanted to know what made a bat as good as it could be and spent time with the craftsmen who made [his] Louisville Sluggers to understand how to maximize their potential. In fact, he once called his first visit to Hillerich & Bradsby’s Louisville Slugger bat factory “. . . one of the greatest things I ever did in my life.”65 Williams always seemed to be looking for the slightest edge over pitchers. He was known by bat factory employees at Hillerich & Bradsby as the player who climbed over piles of lumber, looking for the perfect piece, which included 10 growth rings or fewer per inch. When he found it, he showed the lumber to one of the craftsmen, and demanded that his bat be made from this particular chunk of wood. Williams wanted the best tools of the trade, and he got them. “Everybody said I got the best bats in the league,” he said.66

Williams wasn’t the only MLB player to demand a particular piece or type of wood. The man who signed Williams on a scouting trip to California in the 1930s was also very particular about his lumber.

Eddie Collins, then the general manager of the Boston Red Sox, had enjoyed a 25-year career beginning in 1906 and spanning the Deadball Era and the roaring ’20s.67 He hit third and played second base for both Philadelphia and Chicago in the American League, collecting over 3,300 hits and leading the Athletics to three World Series championships. But Collins was remembered by Louisville Slugger employees for probing through stacks of wood for just the right cut.68

Collins wanted all of his bats made from the heart of the tree. Since heartwood is darker than the lighter-colored sapwood, his bats often were reddish or dark brown on one side and white on the other. Input — or special requests — from major leaguers to bat-makers is encouraged as long as the contribution conforms to the rules of the game. Williams and Collins are two prolific hitters who stand out for their finicky, but legal, demands.69

Heavy bats made a short-lived comeback in the 1960s with a few marquee players. Roberto Clemente sometimes swung a 39-ouncer, and Orlando Cepeda and Dick Allen hefted bats that weighed 40 ounces or more.70 Clemente often took a couple of bats to the on-deck circle, making his final selection on “feel,” intuition, and the tendencies of the pitcher. In spite of these star players, lighter weight bats were in MLB to stay. For example, Hank Aaron primarily used a 31-32 ounce bat, and Rod Carew won seven batting average titles swinging a 32-ouncer.71 Joe Morgan carried a lightweight, 30-ounce bat to the plate.72 Even David Ortiz swung a 32-ounce bat early in his career, and later switched to 31½ ounces.73 More recent stars like Bryce Harper (31-33 ounces), Mike Trout (average of 31¾ ounces), Kris Bryant (31 ounces) and Joe Mauer (31-33 ounces) swing light lumber.74

In 1920, most bats used by major leaguers were typically no lighter than 36 ounces. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, bat racks in MLB held few bats heavier than 36 ounces. Of course, the range of weight, length, wood type, shape, handle diameter, and other bat factors vary from player to player.75

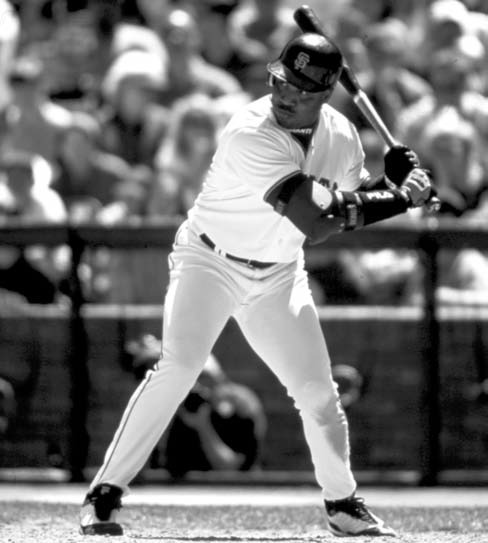

Before Barry Bonds’s 73 home run season in 2001, few players had ever used a maple bat, let alone on a regular basis. Seven years later, about half the bats in the major leagues were maple. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Maple-Bat Era (approximately 2000 to present)

When Derek Jeter broke into the big leagues in 1995, he used a 32-ounce white ash Louisville Slugger with a length of 34 inches.76 The Jeter bat is one of many examples of the dominance of ash as the preferred wood for bat-making through the twentieth century. However, wood enthusiasts and bat gurus continued to experiment with new innovations, including looking for a new wood that would give the batter an advantage. One such innovation was hard maple.

Joe Carter of the Toronto Blue Jays was the first MLB player to use a maple bat in a game, in 1997. He was also the first to hit a homer with one.77 Carter said, “When you first use them, it’s a totally different feel from a normal [ash] bat. I mean, totally different. After you use them, you don’t want to go back.”78

Maple has long been a fixture in the sporting world because of its hardness and durability. Many of the hardwood floors used for basketball courts are made from maple. The different shades of maple (called “grades”) give many courts a distinct appearance. Of the 30 National Basketball Association courts, 29 are made from maple (the Boston Celtics court is oak).79

In the middle of the 1999 season, Barry Bonds of the San Francisco Giants began using a maple bat full-time. In 2001, he used a 34-inch, 32-ounce hard sugar maple model with a half-cupped barrel. Bonds’ bat was crafted for him by Canadian Sam Holman, who had the experience of over two decades in the carpentry business. In 2001 season, Bonds crushed single-season records for home runs (73) and slugging average (.863) using his custom-made Sam Bat. After Bonds’ power display, maple bats surged in popularity in the major leagues. Many players believed that maple added home runs to their totals (although an exit velocity study demonstrated otherwise).80 As of the 2017 season, approximately three-fourths of big leaguers strode to the plate carrying a maple bat.81 Ash was a distant second-most popular, followed by the up-and-coming yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis).lxxxii

Maple is denser, and thus heavier, than ash. But since most players want lighter lumber, maple bats tend to have thinner handles. As any player, at any level, knows, a thin-handled bat is more likely to break on an inside-pitch. Also, the grain pattern of maple is more difficult to see than ash, leading to inferior bats and difficult-to-detect hairline fractures creeping into the game. Consequently, broken, shattered, and snapped bats were becoming more common in the professional game in the first decade of the twenty-first century.83

In 2008, a wave of incidents involving flying shards of shattered bats swept baseball. On April 15, 2008, Pirates hitting coach Don Long had his left cheek slashed; on April 25, a fan broke her jaw in two places when the barrel of Todd Helton’s bat hit her in the face; and in June umpire Brian O’Nora’s forehead was cut when Kansas City catcher Miguel Olivo’s bat shattered.84

MLB funded a study that explored, among other topics, the likely reason for the high incidence of shattered bats. One of the study’s key findings centered on the anatomical differences between ash (easy to see grain slope) and maple (difficult to see grain slope). MLB adopted recommendations based on this finding, particularly regarding maple. One of the recommendations adopted by MLB was to rotate where the trademark on maple and similar species appeared by 90 degrees, so that hitters would make contact with the hardest wood. MLB also required manufacturers of non-ash bats to place a clear, quarter-sized spot on the traditional trademark side of the bat handle to help inspectors see the grain. These policy changes reduced maple bat “flying shard incidents” from about one per game in 2008 to to less than one every three games in 2016.85

Pests have wreaked havoc on North American trees in the maple-bat era. The emerald ash borer (EAB) and Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) are two invasive insects that have devastated woodlands that supply bat wood to MLB. Because EAB is often spread via the transport of firewood, Hillerich & Bradsby teamed with the Nature Conservancy on a campaign to limit the movement of wood called “Buy It Where You Burn It.”86 ALB feeds on numerous trees, including elm, birch, willow, poplar, and black locust. Unfortunately for baseball, one of its favorite trees to dine on is maple. The U.S. Department of Agriculture soberly reported that the Asian longhorned beetle could inflict worse damage than Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight, and gypsy moths.87 Fortunately, yellow birch has not had the ALB complete a life cycle on it.88

Final Thoughts

Baseball, and in particular the baseball bat, has changed over time. But in the twenty-first century, major-league bats continue to be made from a single piece of wood. As we near the beginning of that century’s third decade, some fans wonder if aluminum or other materials will replace wood as the choice for major-league bats.89 Will maple continue its dominance in the game? What is the future of ash? Are insects like the emerald ash borer, the Asian long-horned beetle, or other invasive pests a serious threat to the trees that produce MLB bats? Is there an alternative species for bat wood, perhaps yellow birch, that will require serious discussion in 20, 50, or 100 years?

However, what is known, and not debated or challenged, is that the sizes, shapes, and species of wood, bat rules, and player bat preferences change over time.

STEPHEN BRATKOVICH, a native of Pennsylvania, is a retired forester and wood products specialist with the US Forest Service and Dovetail Partners, Inc. He currently lives in St. Paul with his wife of 42 years. Steve is a member of the Halsey Hall Chapter of SABR. He is the author of “Bob Oldis: A Life in Baseball,” which chronicles the on-and-off-field tribulations of a major league catcher, coach, and scout. Steve’s next book will focus on MLB bats. Steve roots for the Twins and Pirates and can be contacted at sbratkovich@comcast.net.

Notes

1 Beth Hise, Swinging Away: How Cricket and Baseball Connect (London: Scala Books, 2010), 10, 48.

2 John Odell, ed., Baseball as America (Washington: National Geographic Society and Cooperstown, NY: National Baseball Hall of Fame, 2002), 260–61.

3 Bernie Mussill, “The Baseball Bat: From the First Crack to the Clank,” Oldtyme Baseball News, no. 2 (1998), 21–25.

4 Stuart Miller, Good Wood: The Story of the Baseball Bat (Chicago: ACTA Publications, 2011), 83.

5 Josh Leventhal, A History of Baseball in 100 Objects: A Tour Through the Bats, Balls, Uniforms, Awards, Documents, and Other Artifacts That Tell the Story of the National Pastime (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2015), 201.

6 Miller, Good Wood, 84.

7 Robert Adair, The Physics of Baseball, 3rd ed. (New York: Perennial, 2002), 114, 138.

8 Adair, 114.

9 Dan Gutman, Banana Bats & Ding-Dong Balls: A Century of Unique Baseball Inventions (New York: Macmillan, 1995), xviii.

10 Gutman, Banana Bats, 2-3; Miller, Good Wood, 107.

11 Steve Rushin, The 34-Ton Bat (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013), 60.

12 Baseball: A Film By Ken Burns, episode 1, “First Inning: Our Game,” directed by Ken Burns, written by Geoffrey C. Ward, Burns, PBS, 1994.

13 Gutman, Banana Bats, 7; Miller, Good Wood, 84.

14 Bob Hill, Crack of The Bat: The Louisville Slugger Story (Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing, 2002), 7; Gutman, Banana Bats, 7. Second growth is a forest that grows up after a disturbance and leads to trees being replaced. In the case of ash, the tree replacement is typically from seed of nearby trees.

15 John Thorn, “A Peek into the Pocket-book,” Our Game, April 19, 2016, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/a-peek-into-the-pocket-book-a9bd03dfe31d (accessed May 1, 2017).

16 David Magee and Philip Shirley, Sweet Spot: 125 Years of Baseball and The Louisville Slugger (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009), 8.

17 Leventhal, A History of Baseball in 100 Objects, 2015; Adair, The Physics of Baseball, 130.

18 Scott Drake, vice president of business operations for baseball bat manufacturer PFS Teco, author interview, April 5, 2017.

19 Unnamed source, author interview, February 28, 2017.

20 Leventhal, A History of Baseball in 100 Objects, 37, 73. The NABBP was replaced by the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NA) in 1871. In 1876, the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs was formed, and still exists today.

21 Leventhal, 37, 203.

22 Miller, Good Wood, 84.

23 Magee and Shirley, Sweet Spot, 22.

24 Gutman, Banana Bats, 10; Miller, Good Wood, 84.

25 Leventhal, A History of Baseball in 100 Objects, 203.

26 Tom Lepperd, ed. Official Baseball Rules: 2018 Edition (New York: Office of the Commissioner of Baseball, 2018), 5 (MLB rule 3.02 a).

27 Gutman, Banana Bats, 26.

28 Miller, Good Wood, 89.

29 Lepperd, ed. Baseball Rules: 2018, 5 (MLB rule 3.02 b).

30 Filip Bondy, The Pine Tar Game: The Kansas City Royals, the New York Yankees, and Baseball’s Most Absurd and Entertaining Controversy (New York: Scribner, 2015), 5.

31 Bondy, 4.

32 Bondy, 4-6, 144–45, 148, 162–63.

33 Leppard, Baseball Rules 2018, 5.

34 Hill, Crack of the Bat, 4–6.

35 Lawrence Ritter, The Story of Baseball, 3rd ed. (New York: Morrow Junior Books, 1999), 26–27.

36 Adair, The Physics of Baseball, 114.

37 Hill, Crack of the Bat, 6; Miller, Good Wood, 22–23.

38 Charles Leerhsen, Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 36.

39 Leerhsen, 96.

40 Hill, Crack of the Bat, 10; Miller, Good Wood, 84; Leerhsen, Ty Cobb, 201, 324, 361. In Sweet Spot, Magee and Shirley, note that the first bat order Cobb placed for his Louisville Slugger was 32 ounces, and that Cobb got most of his hits with a Louisville Slugger.

41 Miller, Good Wood, 84.

42 Miller, 21–22.

43 Miller, 21–22.

44 Ritter, The Story of Baseball, 26, 28; “Spitball,” Baseball Reference Bullpen, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Spitball; “Baseball (ball),” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baseball_(ball) (both sites accessed August 22, 2018).

45 Ritter, 86; Leventhal, A History of Baseball in 100 Objects, 197.

46 Hill, Crack of the Bat, 11; Miller, Good Wood 86.

47 Miller, 21.

48 Miller, 7.

49 Adair, The Physics of Baseball, 115.

50 Leerhsen, Ty Cobb, 307.

51 Adair, The Physics of Baseball, 105–106.

52 Ron Selter and Phil Lowry, author interviews, August 25, 2018; Curt Smith, Storied Stadiums: Baseballs History Through its Ballparks (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2001), 123. Thanks also to an anonymous reviewer of an earlier article draft.

53 Leerhsen, Ty Cobb, 308.

54 Leventhal, A History of Baseball in 100 Objects, 194; Leerhsen, Ty Cobb, 309.

55 Leerhsen, 308.

56 “Ted Williams,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/willite01.shtml (accessed August 19, 2018).

57 Magee and Shirley, Sweet Spot, 68; Ritter, The Story of Baseball, 117.

58 “Ted Williams,” Baseball Reference.

59 Ted Williams, My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1969), 54, 173; Hill, Crack of the Bat, 10.

60 Miller, Good Wood, 13; Hill, Crack of the Bat, 10.

61 Williams, 54.

62 Williams, 54–55, 109.

63 Williams, 55; Magee and Shirley, Sweet Spot, 71.

64 Gutman, Banana Bats, 33; Magee and Shirley, 71.

65 Magee and Shirley, 64, 68.

66 Magee and Shirley, 68; Miller, Good Wood, 13.

67 Paul Mittermeyer, “Eddie Collins,” SABR Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c480756d (accessed June 13, 2017).

68 Magee and Shirley, Sweet Spot, 29.

69 Magee and Shirley, 29.

70 Miller, Good Wood, 87.

71 Adair, The Physics of Baseball, 115 (Aaron’s bat); Hill, Crack of the Bat, 10 (Carew’s bat).

72 Miller, Good Wood, 23.

73 Miller, 55.

74 “Bryce Harper’s Bat”; “Mike Trout’s Bat”; “Kris Bryant’s Bat”; Bat Digest, https://www.batdigest.com/mlb-bats (accessed September 1, 2018); “Joe Mauer,” VintageBats.com, http://www.vintagebats.com/feature_page-JoeMauer.htm (accessed August 4, 2017).

75 Adair, The Physics of Baseball, 113.

76 Magee and Shirley, Sweet Spot, 128.

77 Miller, Good Wood, 53–54.

78 Miller, 91.

79 Tim Newcomb, “Facts about floors: Detailing the process behind NBA hardwood courts,” Sports Illustrated, December 2, 2015, https://www.si.com/nba/2015/12/02/nba-hardwood-floors-basketball-court-celtics-nets-magic-nuggets-hornets (accessed June 26, 2017).

80 Miller, Good Wood, 91-92; Stephen Canella, “Good Wood,” Sports Illustrated, March 25, 2002, https://www.si.com/vault/issue/703412/108/2 (accessed November 27, 2017).

81 Scott Drake, author interview; Everett Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 3rd ed., (New York: Free Press, 1983).

82 Scott Drake, author interview.

83 Miller, Good Wood, 91–93.

84 Lou Dzierzak, “Batter Up: Shattering Sticks Create Peril in MLB Ballparks,” Scientific American, July 14, 2008, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/baseball-bat-controversy (accessed August 26, 2018); Dave van Dyck, “Shattering maple bats raise concerns,” Chicago Tribune, May 25, 2008, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2008-05-25/sports/0805240422_1_maple-bats-major-league-baseball-darts/2 (accessed September 1, 2018).

85 Scott Drake, unnamed source, author interviews.

86 “Transported firewood can spread devastating invasive species,” the Nature Conservancy https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/urgentissues/land-conservation/forests/firewood-buy-it-where-you-burn-it.xml; “About,” DontMoveFirewood.org, https://www.dontmovefirewood.org/about (both accessed August 26, 2018).

87 U.S. Forest Service personnel, author interview, March 6, 2017.

88 “Asian Longhorned Beetle: Annotated Host List,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, January 2015, https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant_health/plant_pest_info/asian_lhb/downloads/hostlist.pdf (accessed August 26, 2018).

89 In 1989, Peter Gammons wrote in Sports Illustrated: “Like it or not, the crack of the bat is inevitably being replaced by a ping. By the turn of the century even the majors will probably have put down the lumber and picked up the metal.” Gammons, “End of an Era,” Sports Illustrated, July 24, 1989.