The Best Last-Place Team Ever? 1966 Yankees Didn’t Know How to Finish Last

This article was written by David Surdam

This article was published in 2002 Baseball Research Journal

The 1967 Sporting News Baseball Guide reported “Many observers felt [the 1966 Yankees] to be the best tenth-place team in major league annals.” If they couldn’t capture yet another pennant, at least they could be the best at finishing last.

The 1966 Yankees boasted two Hall of Fame players in Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford, as well as two other former Most Valuable Players in Elston Howard and Roger Maris. There was one former Rookie of the Year recipients on the team: Tom Tresh. Clearly there

was plenty of talent.

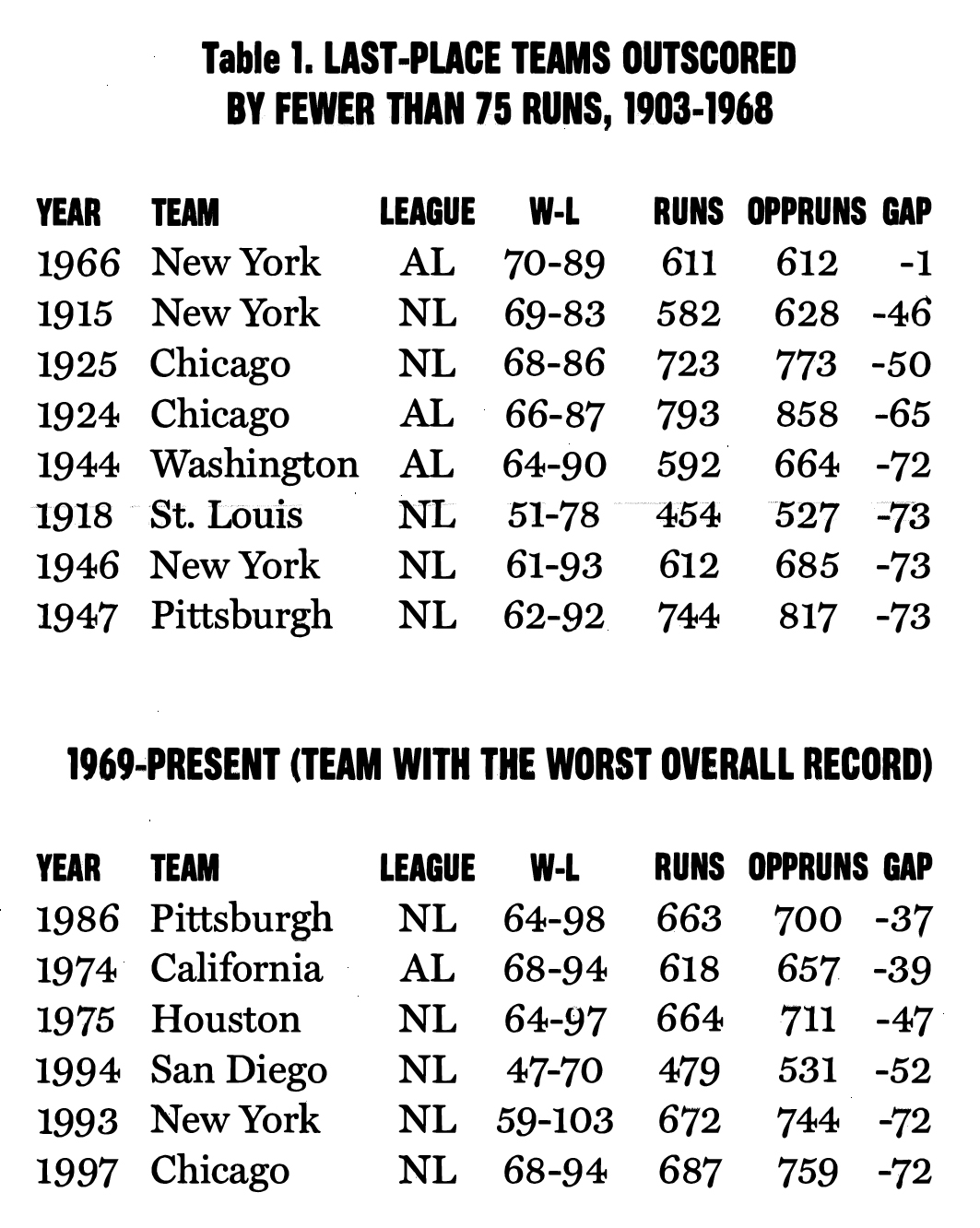

What sets the team apart, though, is its near miss. No, not a near miss in the pennant race; the team finished 26.5 games out of first place, which wasn’t terribly far back for a last-place team. No, the team nearly missed outscoring its opponents over the season. The Yankees scored 611 runs while allowing 612. Normally a team with such a close disparity would be expected to finish near .500. But the Yankees finished 70-89. In the pre-divisional era (1903-68), the Yankees’ achievement is impressive. No other last-place team came within 46 runs of outscoring their opponents during the season (see Table 1). Only eight teams came within 75 runs of doing so. On average, last-place teams tended to be outscored by 210 runs in the American League and 195 runs in the National League before divisional play. Surprisingly, during the first expansion period (1961-68 in the American League and 1962-68 in the National League), last-place teams were outscored by only 147 runs per season in the American League and by 212 runs in the National League. Du1ing the divisional era, six more teams with the worst won-loss records came within 75 runs of outscoring their opponents.

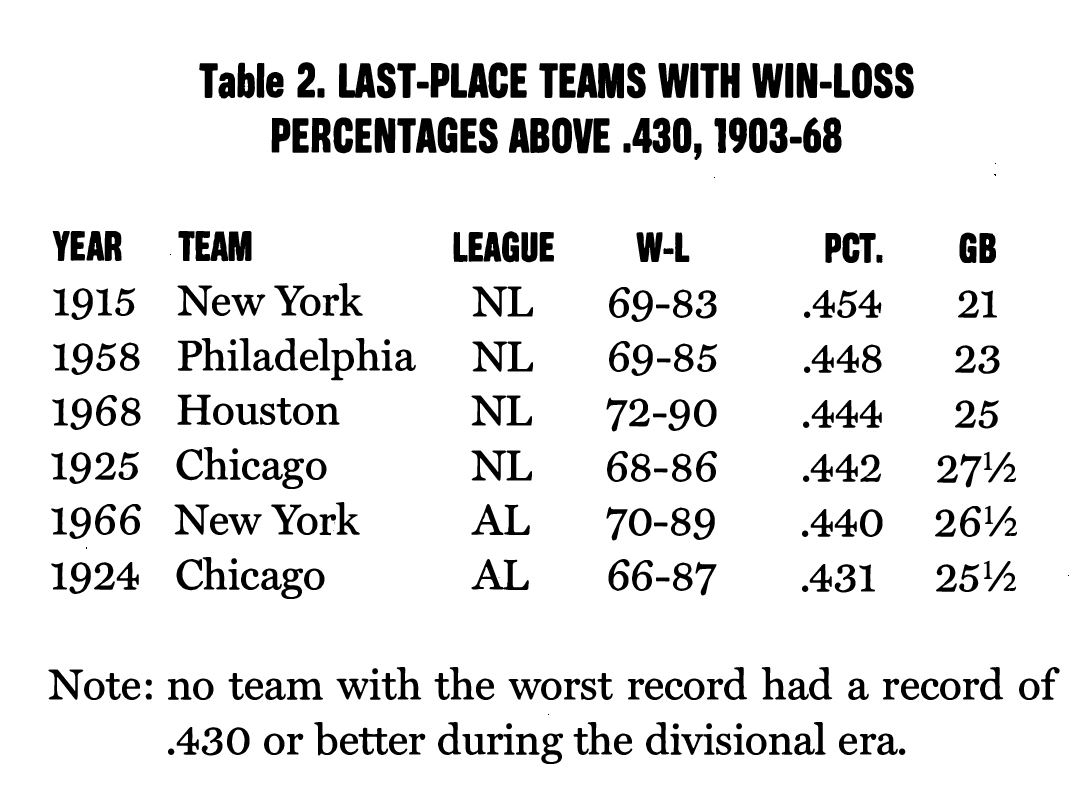

The 1966 Yankees’ win-loss mark was the fifth-best percentage (.440) compiled by a last-place team in the pre-divisional era (see Table 2). Clearly, the Yankees were superior cellar dwellers. The 1915 New York Giants :finished with a 69-83 record (.454), which is the highest mark ever for a last-place team. The Giants were two seasons removed from a pennant-winning season. Only four other last-place teams compiled a .431 or better record. During the divisional era, the team with the worst won-loss record always had worse than a .430 mark.

The Yankees’ team ERA that season was slightly lower than the league average (3.42 versus 3.44), but the Bronx Bombers produced fewer than the average number of runs. The team’s fielding record was slightly worse than the league average (.977 versus ,978), and the team completed slightly fewer double plays than average. Indeed, the team was consistently slightly below average. The team’s 15-38 win-loss record in games decided by one run was telling.

How did the team flounder so badly in 1966? Going into the season, general manager Ralph Houk exuded confidence in a February 5, 1966, The Sporting News article. Houk claimed that the defending American League champion Minnesota Twins had a clear-cut edge at only one position: shortstop. The Twins boasted MVP Zoilo Versalles at shortstop, while the Yankees had acquired Ruben Amaro from the Phillies to replace the retired Tony Kubek. Clete Boyer, Horace Clarke, Bobby Murcer, and Dick Schofield would all get tryouts at shortstop during the season. Otherwise, Houk felt the Yankees had as strong a pitching staff and superiority at five of the eight fielding positions (with the remaining two positions being standoffs).

Unfortunately, the four biggest stars on the team continued their deterioration that started in 1965. Mantle (.288, 23 home runs) and Maris (.233, 13 home runs) each had fewer than 400 at-bats. Elston Howard, MVP in 1963, hit .253 with only six home runs. Whitey Ford was on the injured list for most of the season and had his first losing record (2-5) despite a 2.47 ERA. Mel Stottlemyre went from being a 20-game winner to a 20-game loser. Former twenty-game winner Jim Bouton continued his ineffectiveness with a 3-8 record, although his 2.70 ERA suggests that his teammates were more responsible. Reliever Pedro Ramos lost his effectiveness.

The Yankees’ descent from the five consecutive pennants between 1960 and 1964 wasn’t a one-year odyssey: by 1965 the New York Yankees dynasty was in disarray. The team had its first sub-.500 record since 1925. The team finished sixth, its worst finish since 1925. Of course, the team’s pennant in 1964 was not awe-inspiring. The Yankees won a tough three-team pennant race by a single game.

In retrospect, the warning signs were apparent in 1964. Stars Mickey Mantle, Elston Howard, and Whitey Ford were over 30; Mantle was an old 32 during 1964. In the few years before the 1964 season, the team had introduced new blood in Tom Tresh, Joe Pepitone, Al Downing, Jim Bouton, and Mel Stottlemyre; Stottlemyre won nine of twelve decisions to help the Yankees clinch the pennant. The late-season acquisition of Pedro Ramos steadied the bullpen. Unfortunately, standouts Roger Maris, Ralph Terry, and Tony Kubek were slipping badly.

The team fired Yogi Berra after the World Series loss, and Johnny Keane, manager of the champion St. Louis Cardinals, took over. Unfortunately for Keane, Mickey Mantle got injured in 1965 and would never be a great player again. Whitey Ford pitched 244 innings, but his ERA was half a run above his lifetime average. Roger Maris suffered through injuries and hit only eight home runs. Elston Howard, too, was injured. Tony Kubek continued his slump and would soon retire. Mel Stottlemyre won 20 games, but Jim Bouton won only four games. No effective reinforcements were on the way. Mike Hegan and Jake Gibbs would have lengthy mediocre careers. The injuries contributed to the Yankees’ 77-85 record, a drop of 22 wins.

The Yankees did not trade for an established star between 1965 and 1966. There were a few good players available, including Frank Robinson, but Baltimore acquired Robinson for Milt Pappas. All Robinson did was win the Most Valuable Player Award in 1966. Ted Abernathy and Ferguson Jenkins were traded during the 1966 season. Abernathy led the National League in saves in 1965 and 1967, although he slumped badly in 1966. Jenkins was just beginning and would not become a prolific winner for another season. Former National League Most Valuable Player Bill White was also available after the 1965 season. The Yankees acquired Ruben Amaro and Bob Friend, and later purchased Lu Clinton, Al Closter, and Dick Schofield. Friend was near the end of his fine career, and Schofield shared shortstop duties with the mediocre Amaro. The team promoted Horace Clarke, Fritz Peterson, Roy White, and Bobby Murcer. Peterson led the team in wins with 12, and Clarke hit .266 as one of Kubek’s replacements.

Although Bobby Murcer would become a solid outfielder, Horace Clarke was a mediocre player throughout his career. The Yankees would later introduce Rookies of the Year Stan Bahnsen and Thurman Munson, but the farm system was not as prolific as during the 1950s. Indeed, observers attributed the minor league talent dearth to George Weiss’s refusal to pay bonuses during the 1950s, and to the death of key scouts, including Paul Krichell. Although the Yankees introduced several solid players during the 1960s, there would be a long drought after Mickey Mantle. Indeed, one could argue that the franchise has failed to introduce a superstar of the Gehrig, DiMaggio, and Mantle caliber in the intervening 50 years since Mantle’s debut.

The 1966 Yankees’ last-place finish was hotly disputed. The expansion Senators finished 25 1/2 games back of the pennant-winning Minnesota Twins, while the Boston Red Sox finished 26 games back. Thus, there was a dogfight for last place. The Red Sox completed the “Impossible Dream” in 1967 by winning the pennant, while the Senators continued to wallow in the second division with the Yankees.

Still, the 1966 Yankees make a strong case for being the best last-place team in history. Their win-loss mark and run differential were stellar for cellar dwellers.

DAVID SURDAM is adjunct associate professor of economics at the Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago. He is finishing his book: The Postwar New York Yankees and America: An Economic, Social, and Baseball History.

SOURCES

Thorn, Palmer, & Gershman. 2001. Total Baseball. 7th Edition.