The Best-Pitched Game in Baseball History: Warren Spahn and Juan Marichal

This article was written by Jim Kaplan

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 27, 2007)

Like raging dinosaurs in some prehistoric swamp, the Milwaukee Braves’ Warren Spahn and the San Francisco Giants’ Juan Marichal slugged it out for four hours, 10 minutes, and 16 innings, all through the night of July 2 and into the early minutes of July 3, 1963. Spahn, 42, personified an aging Tyrannosaurus rex defending his grip on the animal kingdom with wits, tenacity, and memory. Marichal, 25, embodied an emerging Mapusaurus roseae: young, strong, fast, and confident. By the time their epic standoff ended with a single run at 12:31 a.m, they had completed a battle of the ages for any species. It was arguably the greatest pitching duel in baseball history.

Never have two Hall of Famers pitched as well over such an extended game in which each faced a lineup of fellow Cooperstownians and other fine players. In addition to Spahn and Marichal, Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Orlando Cepeda of the Giants and Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews of the Braves were bound for induction. Other substantial hitters included Braves left fielder Lee Maye, who had sizzled all June, and Giants third baseman Harvey Kuenn, catcher Ed Bailey, and right fielder Felipe Alou. For that matter, Spahn, who would lead all National League pitchers with 35 career homers, and Marichal, who batted over .500 with men on base one season, wielded mean bats themselves.

So how did Spahn and Marichal repel these fearsome hitters past midnight? The stars and their stars had to be properly aligned. Entering the season, the strike zone had been expanded from “knees to armpits” all the way to “knees to top of shoulder level.” The Giants and Braves were playing night ball at San Francisco’s typically breezy, chilly Candlestick Park, a pitcher’s paradise because balls don’t carry as far in cold weather as they do when it’s humid.

July 2 was cool, with the usual west-to-east wind rippling across from left-center to right-center that presented a major obstacle for right-handed batters and helped left handers but sometimes sent shots by lefties into foul territory. So it was a pitcher’s night at a pitcher’s park. And the game began with Spahn and Marichal, two of the hottest pitchers in baseball. Spahn won four times in April and was 11-3 with five straight victories by July 2. He had just shut out the Dodgers and hadn’t allowed a walk in 18½ innings. Moreover, he was facing precisely the same eight position players he had no-hit in April 1961. Marichal, who had won 13 games as a rookie and 18 in his second year, was already 12-3, with eight straight wins. He had no-hit Houston, 1-0, just 17 days earlier, getting 23 infield outs and throwing only 89 pitches despite two walks.

Warming Up on a Cold Night

Marichal took his warm-up pitches from the bullpen mound rather than on the sideline, because it was closer in height to the one on the diamond. In competition, he toed the inside of the rubber closest to first base to improve the angle for pitching away from left-handed hitters and to give his slider more room to break away from right handers. “When we had a meeting before the game, it was only Mays, Bailey, and myself,” Marichal says. “Willie would direct the left fielder and right fielder where to play. Having Willie behind me made my position easier.” He had no idea at the time how prophetic those words would be on July 2, 1963.

Spahn’s warm-ups, this day as every day, seemed perfunctory.” He used to drive me crazy,” says Spahn’s son Greg, a real estate executive. Greg was born on the eve of the 1948 World Series and hit .524 as a high school senior but had to give up baseball when shoulder problems sidelined him at the University of Oklahoma. “He’d throw five pitches on the sideline, then talk to someone, throw another five and then talk.” But there was method to Spahn’s pre-start madness.The joking kept him loose: “The more pressure I feel, the more I kid around.” The pitches had purpose. “He’d throw five fastballs, five screwballs, five curves, five changeups,” Greg continues, “and see what was working If he had trouble, it was usually in the first or second inning. Then he’d figure out what to do.”

Spahn and Marichal weren’t overpowering but shared excellent control, a fine repertoire of pitches, and a high leg kick that obscured a batter’s sightlines. As catcher Del Crandall explained, Spahn showed the batter three things: the sole of his right shoe, the back of his glove, and finally the ball. Spahn leaned forward in an almost courtly bow to the hitters, then rocked back, his right leg raised above his head in what The Sporting News’s Dave Kindred called a five minutes to six position, followed by an overhand delivery that was as smooth and regular as a dipping oil-field pumping jack back home in Oklahoma. Since every pitch was thrown with the same motion, the batter had no idea what to expect.

And there was something else. Because of an old separated shoulder from high school football, Spahn couldn’t raise his right hand higher than his shoulder. As he moved toward the plate, his glove rose slowly, then descended quickly through the hitter’s line of vision. “People kept telling me that the motion of the glove really bothered hitters,” Spahn told Kindred.”So I kept doing it. Whatever bothered hitters, I was for.”

No one was sure what they’d seen from Marichal. Richie Allen thought he threw five pitches, Joe Torre said seven, Billy Williams 12, and Lou Brock 16.”People were intrigued by his motion, but he was as much ball as motion,” Bailey says.”Juan was not a pattern-type pitcher. He was unorthodox.” What amazed fellow Giant pitcher Bobby Bolin was his control: “With that kick I don’ think anyone else could keep his body pretty straight and get the ball over.”

In the Beginning

Marichal and Spahn sailed through the first three innings, Marichal yielding one hit, Spahn one, Marichal getting the most mileage out of his fastball, Spahn learning quickly that his screwball was getting right-handed hitters while his curve curbed lefties. More than anything, acquiring the screwball after he was supposedly washed up 10 years earlier had crossed up righties and extended Spahn’s career.

Orlando Cepeda ‘s stolen base in the second inning must have infuriated Spahn.He had one of the best pick-off moves in baseball, one so sure and sudden that he picked off Jackie Robinson twice in one game. Even Lou Brock was cautious about running on him. Cepeda, who stole eight bases that season and 142 in his career, probably ran on catcher Crandall rather than pitcher Spahn.

Sailing Through the Sixth

Hank Aaron led off the fourth by flying out deep to left field, the wind holding up his drive. Marichal got Eddie Mathews on strikes, but Norm Larker walked and Mack Jones singled him to second, bringing up Crandall. Frequently Spahn’s personal catcher, Crandall knew Spahn so well he was rarely shaken off. Crandall would bat only .201 in 1963. But there would be no easy outs, no pit stops that July night. With two out and two on, Crandall hit a sinking liner to center. Willie Mays elected to one-hop it rather than dive, and he nailed Larker at the plate in “one amazing motion,” according to the Chronicle’s Stevens, and on a” 100 percent perfect peg,” according to his colleague Bill Leister.

Menke replaced the sore-legged Mathews in the fourth and got two hits and a stolen base before the game played out. No easy outs, no pit stops.Through six scoreless innings, Marichal had a four-hitter and Spahn a two-hitter.

Cruising Through Nine

Marichal was throwing plenty of fastballs now. The Braves blew a chance to go ahead in the seventh when Crandall singled and was thrown out at second after shortstop Roy McMillan swung and missed on a hit-and-run. If he’d stayed put, Crandall might have scored when Spahn himself doubled off the fence in right field. Marichal got out of the inning and breathed easily. “Did you see [Spahn] hit that ball?” Marichal asked after the game. “It was going out of the park, and then that wind caught it. What a break that was!”

Marichal was being a good sport, because the wind probably helped Spahn’s drive. In the eighth, Ernie Bowman replaced Jim Davenport (who had earlier re placed Jose Pagan) at shortstop; after Aaron walked, Bowman made a great stop in the hole to throw out Menke. Aaron moved to second on the play but was left there when Larker flied to Willie McCovey. With the game still scoreless in the ninth, it was Spahn’s turn to breathe a sigh of relief. When McCovey launched one of his patented moon shots, the ball flew somewhere over the right-field foul pole. It was called foul by first base umpire Chris Pelekoudas, fair by the Giants, the fans, and most of the swells on press row. “The ball was foul when it left the bleachers, but fair when it passed over the fair pole,” Marichal says.

The Giants protested bitterly but futilely and went down 1-2-3.

Extra Innings

So on to extra innings with these worthies. It was not unusual at the time for pitchers to work overtime, and downright commonplace for Spahn and Marichal. Between 1947 and 1961, Spahn started 531 games (including the World Series). Fifty-two of those games went into extra innings; Spahn completed 23 of them and pitched into the 10th inning without getting a decision three other times. He also had pitched in what might be called extra-extra innings, losing a 15-inning game in 1952 and a 16-inning game in 1951. For his part, Marichal had lost a 17-inning game while pitching for Springfield, MA, in 1959.

There was not just stamina at work but incentive. Both men had been denied moments of greatness they must have coveted. Granted, Marichal had his no-hitter. Still, he bruised the index finger of his pitching hand and lost a fingernail while bunting in the 1962 World Series and had to leave a game he was winning in the fourth inning, never to reappear in a fall classic. Spahn had plenty of thrills, but not the one schoolboys dream of. Sure, he and Johnny Sain had been immortalized by the “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” poetry during the 1948 pennant drive. Yes, in the World Series Spahn lost his only start, in game two, and won game five with 5 ½ innings of one-hit, seven-strikeout relief. Granted, he was Pitcher of the Year in 1957 and won a 10-inning game while los ing another, 3-1, in the Series, but he fell sick with the flu and watched from his hotel room when Lew Burdette took Spahnie’s scheduled start on two days’ rest and beat the Yankees in game seven. Spahn was 2-1 in the 1958 Series, losing only in extra innings, but the Yankees won in seven games.

Even the extraordinary no-hitters Spahn pitched at ages 39 and 40, throwing tantalizing sliders and screwballs the batters couldn’t wait to hit but missed or grounded to short, hadn’t moved him inordinately. “No-hitters aren’t that much fun,” he told Jim Thielman, who writes cool of the evening.com. “Every pitch you make can blow it, and you go out there in the ninth inning and look around and all the infielders are scared because they’re going to screw it up.”

After nine innings, Spahn had allowed five hits and Marichal six. While Greg Spahn and 15,920 other fans sat shivering in the stands, the pitchers heated up. Spahn walked his duck walk slowly to the mound, “head down, taking his good old time,” in the words of another Braves pitcher, Bob Sadowski. Marichal had always run to the mound and raced through his warm-ups to combat the Candlestick cold, and this night was no exception. “You were supposed to take seven warm-up pitches, but I’d run to the mound and sometimes take eight, nine, or 10,” Marichal said on the phone from Santo Domingo. “Then I’d run from the mound to rest longer.”

The Braves appreciated Marichal’s hurry-up style, which was never intended to show up his plodding opponent. When the Giants were batting, Marichal sat with a warm-up jacket, a towel over his pitching hand to keep his fingers loose, chewing Bazooka gum. “I chewed it so hard, people thought I’d get tired, but it helped me concentrate,” he says. He retired nine straight batters in innings 10-12. Spahn yielded a single bunt hit. Neither pitcher wanted to be taken out. Every inning after the ninth, Marichal said he told manager Alvin Dark, “Alvin, do you see that man pitching on the other side? He’s 42 and I’m 25 and you can’t take me out until that man is not pitching.”

Memory is a cruel mistress. Looking back over the years from his South Carolina retirement, Dark remembers a different conversation. “Larry Jansen, who won 23 games for the Giants in 1951 and then hurt his arm, was our pitching coach, so we were very conscious about pitchers working too long and injuring themselves. We had just started keeping pitch counts. ‘I don’t want this kid to get hurt,’ I was thinking. I kept going to the mound the last three or four innings asking Juan, ‘Are you all right?’ And he always said he was.”

Dark admits that Marichal passed any conceivable pitch count, but he wasn’t worried. “If a guy gets wild or starts getting his pitches up, you know his arm might be tired, but that wasn’t the case with Juan.” Dark never asked a reliever to warm up.

Milwaukee manager Bobby Bragan insists he never even went to the mound. “I was a member of the Phillies [1940-42], and I can remember hearing that Connie Mack of the Philadelphia A’s would take three pitchers to Detroit for a weekend series,” says Bragan, who still runs a youth foundation in his 90th year. Not only could Spahn and Marichal pitch any length of a complete game, Spahn’s old manager insists, they could throw a fastball, curve, or change up on any count. Just watching Spahn and marveling, Bragan can still see his absolute concentration: “When he was pitching, he would walk by his brother.”

Denouement

People have always wondered what it was like on the bench as the game moved from memorable to historical. Did players turn to teammates and say, “I’m going to tell my grandchildren about this one?” In truth, they were just trying to get through the night,” says Frank Bolling, who played all 16 innings at second for the Braves, going 2-for-7 at the plate and handling seven chances without an error. “When you’re in a game like that, you don’t think of anything until it’s over. You just want someone to score.”

As the game progressed, Spahn was drinking very little water, because it gave him a stomachache. But what Spahn did touch was unusual, to say the least. When he and Burdette were teammates, the guy pitching would come off the field and find his friend waiting in the run way behind the dugout holding a lit cigarette for him. “There was no rule against smoking when people can’t see you,” Burdette says. On July 2, 1963, Burdette was a Cardinal, so Spahn probably lit up an unfiltered Camel on his own. He smoked while chewing Beechnut gum Spahn kept adding sticks during a game, leaving him with a large chunk in his mouth that gave the erroneous impression he was chewing tobacco.

In the Giants’ 13th, Bowman singled, then wandered too far off first. Spahn threw behind him, and Bowman was retired in the ensuing rundown: pitcher to first to shortstop. But the old man appeared to be weakening. In the 14th, Kuenn doubled to lead off, and Spahn intentionally passed the dangerous Mays, ending his consecutive walkless streak at 31½ innings. McCovey fouled to the catcher and Alou flied to center, but Cepeda loaded the bases when Menke made an error. Bases loaded, two outs: the game’s most dramatic moment. Bailey lined to Mack Jones in center. Whew! With a second chance, Spahn retired the side in order in the 15th.

Meanwhile, Marichal was cruising. He gave up a harmless single in the 13th, a walk in the 14th, nothing in the 15th. The 16th inning started around 12:20. Under the curfew in effect, no inning could start after 12:50.

Hardly anyone had left the park. The wind had died down. Marichal got through the top half surrendering only a two-out single to Menke.

Marichal had thought each of the last three innings would be his last. “After I pitched the 16th inning, I walked off slow, waiting for some of the players coming in from the outfield” he told the Oakland Tribune. “I was waiting for Willie Mays. I said, ‘Willie, this is going to be the last inning for me. He said, “Don’t worry Chico I’m going to win this game for you.”

In the bottom of the 16th, Spahn threw one screwball after another to the right-handed Kuenn, getting him at last on a fly to center. The pitch that extended his career was extending the game.

As Mays stood in the on-deck circle, Marichal called to him “Hit one now.” His teammates chuckled, Mays stepped in. He had been limited to two outfield flies, two infield grounders, a strikeout, and an intentional walk. Swelling now, Spahn threw another scroogie to Mays. And suddenly it was all over.

The screwball hung, Mays swung. “You never knew for sure in Candlestick Park when the ball was hit anywhere between left-center and right-center because the wind could not hold it up, but this one was hit hard and down the line about 30 feet in the air.” Dark says. In Sports Illustrated, Ron Fimrite described “a high arc to left field, where, after hanging in the night sky for what seemed like an eternity, it landed beyond the fence.”

Giants 1, Braves 0, an eight-hitter for Marichal, with four walks and 10 strikeouts, a nine-hitter for Spahn, with one intentional walk and two strikeouts. Marichal allowed just two singles in the last eight innings, while retiring 21 of 24 batters. Spahn threw 201 pitches, Marichal 227. Pro-rated over Spahn’s 15½ innings and Marichal’s 16 full, Spahn had been throwing on a 147-pitch nine-inning rate to Marichal’s 152.

While Mays rounded the bases and disappeared quickly into the night, the crowd stood and cheered both pitchers and, for that matter, themselves for sticking it out. Each spectator was given the “Croix de Candlestick,” a round orange badge for anyone surviving an extra-inning night game at The Stick. “We were riveted,” says Fimrite. “It was the best game I ever saw.”

“It was the greatest game I’ve ever seen by two pitchers Dark said. And maybe the last of its kind. Since 1960 only Gaylord Perry, on September 1, 1967, pitched 16 innings, and he was taken out for the last five innings of a 21-inning game, the sissy. “If they had that today, they’d fire the manager and general manager-everyone but the players!” Marichal says.

Spahn patiently remained on the field for a broadcast interview. His teammates were silently waiting for him in the clubhouse. When he arrived, everyone stood, applauded, and lined up to shake his hand. “If you didn’t have tears in your eyes, you weren’t nothing,” Sadowski says.

Then the writers converged. “It didn’t break at all,” Spahn said of the last pitch, which left him slumping off the mound. “What made me mad is that I had just gotten through throwing some real good ones to Kuenn.”

It may be that the weather had helped keep Spahn in the game — as Sadowski observes, better to have pitched in 55 degrees than 85. Spahn said he was a little tired. “Look, I made 10 or 12 mistakes in the game,” he added. “I was inside on a lot of right-handed hitters, when I usually pitch them outside, and I got away with it. That gives me a certain amount of satisfaction.

“I had a good curve tonight, too, and I’m pretty proud of that. It gave me a weapon against the lefthanders.”

That wasn’t all. An admiring Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell, who attended the game as director of player development for the Giants, said, “Here is a guy 42 years old who still has a fastball,” he marveled. “He just kept busting them in on the hands of our guys and kept getting them out.” Hubbell added, “He ought to will his body to medical science.”

Of Marichal, who retired 16 straight late in the game, Dark said, “He didn’t throw many breaking pitches, thus tiring his arm, but just kept slipping across the fastball with a loose and fluid motion. He got stronger.”

“Oh, my back,” Marichal said. “But tonight was beautiful.”

After answering reporters’ questions, Spahn spent several hours in the clubhouse drinking beer, with his son and several teammates in attendance, everyone telling him what a splendid job he did in a gallant defeat. After his no-hitter, Marichal had gone to a Spanish language movie house and watched a lousy western. Following the 16-inning win, he held himself upright long enough to let hot water pound his arm in the shower—not everyone used ice in those days—then went home and collapsed into bed.” But I didn’t feel so bad pitching in San Francisco, because of the weather. You don’t lose so much salt. It wasn’t like the night in Philadelphia when I lost 8½ pounds, or the afternoon game in Atlanta when I lost nine.”

The San Francisco Chronicle carried a front-page headline JUAN BEATS SPAHN. “There were lesser page one stories that day—something about a nuclear test ban and the FBI smashing a Soviet spy ring,” Fimrite reported in SI. “But for one day at least, an epic pitching duel dominated the news. It was, I told the guys in the office, a rare exercise of sound editorial judgment.” Despite the banner headline, the game was little more—at least at the time—than a one-day story. “There wasn’t the hype then that there is today,” says Crandall, who like some other players in the game can’t remember a single detail. They were not to be blamed. Exhausted from the long game, thinking of the next one, they had no luxury to sit back and look into history.

Pitching In, Pitched Out

The next day Spahn took Marichal aside in the visitors clubhouse. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall when the winningest pitcher of the ’50s (202) passed on his ineffable wisdom to the winningest pitcher of the ’60s (191). “He said to be careful in your next start,” Marichal says. “He said, ‘I know you pitch every fourth day, but try to take an extra day.’ I only got one. It was almost mandatory to pitch every four days.”

Marichal was thrilled to have beaten “one of the best” and honored to be approached by him. “I learned a lot from that man. When I wasn’t pitching, I would watch him, how he approached batters, how he went in and out, up and down. You learn everyday watching a pitcher similar to you.” Marichal not only learned to pitch like Spahn but think like him: “Sometimes you’ll start with one or two pitches and then switch to another in the later innings.” “[Marichal] worked so easily and smoothly, he should be able to take his next turn or, at most, require one extra day of rest,” Dark said.

Indeed, Marichal got that one extra day of rest, pitched on July 7, and gave up five hits and two runs over seven innings in a 5-0 loss to the Cardinals. He hadn’t lost much stuff, and he hadn’t lost much spirit either, because he was fined $50 for buzzing Bob Gibson. “A few weeks later, I pitched 14 innings in New York,” Marichal says. “I struck out Tommie Agee four times. Then he hit a ball that I think is still going.” [Ed. note: Marichal’s memory is highly faulty. This game actually took place six years later, on August 19, 1969.]

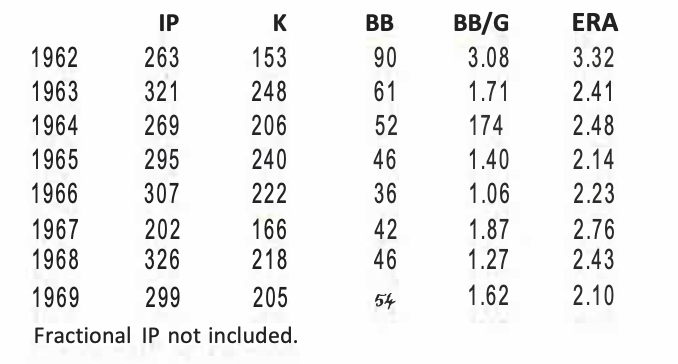

His confidence boosted, his knowledge of hitters and pitching expanded, Marichal pitched 10 of his 18 complete games and got 12 of his 25 wins after July 2. Marichal finished at 25-8, with a 2.41 ERA, his first under 3.00. Equally telling, he broke into the top 10 control artists, finishing seventh with 61 walks in 321 innings, or 1.71per game. And he didn’t let up for the rest of the decade:

In a career lasting from 1960 to 1975, Marichal was one of eight right-handers since 1900 to win at least 100 more than he lost. Extending his career with, yes, a screwball he used effectively against left-handed hitters, he went 243-142, with a sterling .631 winning percent age and equally an eye-catching 2.89 ERA. In eight All-Star games he had an 0.50 ERA. He won 25 games twice and 26 once. He was 37-18 against the arch-rival Dodgers, 24-1 at Candlestick Park. Though he won more than anyone in the 1960s, someone else was always chosen for the Cy Young Award. Marichal never got a single vote during the 1960s, when only one first-place vote was allowed per ballot.

Spahn’s post-7/2/63 life was more complicated. He said that his career went downhill after the game. Well, yes and no. Five days later—yes, he got an extra day off, too—he strained a tendon in his arm throwing a slider to John Bateman but finished the game and beat Houston, 5-0, on five singles. Then he missed the next 18 days before returning on July 25 and losing to Burdette and the Cardinals, 3-1.

Nonetheless, Spahn won six times in 23 days, won 10 of his last 12 decisions, threw three shutouts in September, finished at a jaw-dropping 23-7, and become the oldest pitcher to win 20. His career-low walk total of 49 in 259½ innings decreased for the fourth year in a row, and his 17th consecutive 200-inning season was a modern record. A bargain-basement beauty, Spahn finally pushed his career salary over $1 million. As of this writing, only one player in the last quarter century — Seattle’s Jamie (The Ancient Mariner) Moyer in 2003 — has had a 20-win season past the age of 40.

That said, Spahn declined quickly after 1963. While suffering through a 6-13, 5.69 ERA season in 1964, he said his timing was off and he was pitching defensively. Catcher Bailey believes Spahn’s knees — he would endure seven operations on them, his cartilage torn and ground from high kicks and hard landings — finally got to him. But Spahn wasn’t through playing. After the season he was sold to the Mets, who wanted to use him as both pitcher and pitching coach. Oh, did his presence produce quotes for the writers. “With Berra and him, we are conducting a university this spring,” said Casey Stengel, who had managed Spahn with the Braves and would now oversee him as a Met. And good old Yogi Berra, recruited to warm up Spahn, said, “I don’t know if we’re the oldest battery, but we’re certainly the ugliest.”

Spahn spent the ’65 season with the Mets and Giants — “I pitched for Casey Stengel before and after he was a genius,” he said after departing — before being released with a combined record of 7-16. His final season concluded a 363-245 career and dropped his winning percentage below .600 (.597) while raising his ERA above 3.00 (3.09).

After the 1965 season, no one bid on his services. “I didn’t retire from baseball,” Spahn said. “Baseball retired me.” When Spahn pitched three games for the Mexico City Tigers in 1966 and three games for the Tulsa Oilers in 1967, people got the mistaken impression that he was staging a comeback. Actually, he was demonstrating technique to a Mexican team he was coaching, then trying to improve attendance for an American team he was managing.

Spahn would hold court at the Hall of Fame, thrilling contemporaries like Hank Aaron, Stan Musial, and Willie Mays as well as younger immortals like Johnny Bench and Fergie Jenkins, all the while sucking on a long necked beer. In August 2003, the Braves unveiled a nine-foot bronze statue of Spahn kicking high outside Turner Stadium in Atlanta. Ailing with a broken leg, four broken ribs, a punctured lung, internal bleeding, and fluid buildup in his lungs, Spahn, 82, was wheeled in to see the work. “I took great pride in mooning people,” he said. “That’s the reason I developed that leg kick.”

It was one of the last and best memories of Spahn: kicking and joking. After outliving his wife LoRene by 25 years, Spahn died on November 24, 2003.

Of his father, who came of age during the Depression, Greg Spahn says, “He didn’t buy lavish shoes or clothes. My dad threw away nothing — he was even a string saver. He kept all plumbing fixtures; you never know when you can use one. He kept all 363 balls from his wins, each with the opponent and score on it. I got a friend to crawl through a space in his house, and he found 31 bats.”

One piece of memorabilia remains poignantly missing from the Spahn estate: the last screwball to Willie Mays 31 minutes into July 3, 1963. “That pitch probably bothered him more than any other he ever threw,” Greg says. “For years he said that if he had one pitch he’d like to take back, that was it.”

JIM KAPLAN is former editor of the Baseball Research Journal and author of “Lefty Grove: American Original” (SABR, 2000). He wishes to thank the following SABR members for assistance on this story: Peter C. Bjarkman, Jim Charlton, Bill Deane, Dennis Degenhardt, Roland Hemond, John Holway, Rod Nelson, Crash and Sheila Parr, Jay Roberts, John Zajc, Phil Sienko, Dave Smith, Bob Sproule, Saul Wisnia, and Rich Westcott.