‘The Bikers Against the Boy Scouts’: 1972 World Series and the Emergence of Facial Hair in Baseball

This article was written by Maxwell Kates

This article was published in 1972-74 Oakland Athletics essays

The date was October 14, 1972.

The date was October 14, 1972.

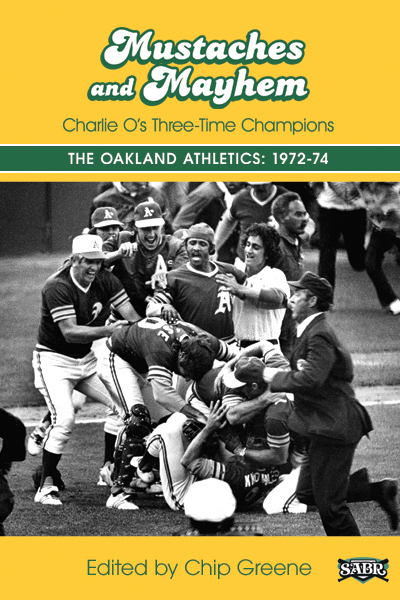

Families across North America gathered around their wood-paneled television sets to watch Game One of the World Series that Saturday afternoon. Many fans in the televised audience had not seen the Oakland A’s or the Cincinnati Reds in a regular-season contest. There stood the Reds along the first-base line wearing businesslike white outfits with minimalist red graphic design, black shoes, short hair, and shaven faces. Meanwhile, the A’s were dressed in green caps, yellow jerseys, white shoes, long hair, and every combination of facial hair imaginable.

“That was a focal point of the media,” analyzed Sal Bando, third baseman and captain of the A’s. “You had more of a radical personality in Charlie Finley, and we had the long hair and the mustaches. And then you take this very conservative, very inflexible Sparky Anderson and the Cincinnati Reds and their short hair and their high socks and their nice pants. It was a contrast between two different styles.”1 Bando imagined that “you probably had the youth of the day rooting for the A’s … [and] the older population rooting for the Reds.”2 True enough, households watching the game probably had more in common with the cartoon Boyles of “Wait Till Your Father Gets Home” than the idyllic families portrayed in television serials from the recent past.

To anyone attending Opening Day at any ballpark during the 1960s, the game appeared untouched by the social changes occurring elsewhere. The attire and attitudes of the players represented a throwback to the Eisenhower era, precisely what the Lords of the Realm wanted. Baseball teams were governed by a cabal of wealthy, conservative older white men. In their estimation, the players were paid to throw strikes and hit curveballs, not to write philosophy or criticize the establishment. Paul Daugherty of the Cincinnati Post illustrated the owners’ fears of being infiltrated by “those stubbly, pinko subversives who thought the Vietnam War worked best as a concept.”

Upon his appointment as general manager of the Cincinnati Reds in 1967, Bob Howsam became the first baseball executive to prohibit his players from growing facial hair.3 Besides banning mustaches, beards, and long hair, players were instructed to wear only black shoes, pants legs at the knee, jackets and ties at all times in public, and to refrain from drinking alcohol on airplanes.4 Many of the managers shared Howsam’s paternalistic stance on player grooming, including George “Sparky” Anderson. Hired by Cincinnati in 1970, Anderson demanded that hirsute players report to the unofficial team barber, relief pitcher Pedro Borbón.5 Many of Borbón’s teammates challenged the rules. As a long-haired rookie in 1971, pitcher Ross Grimsley was ordered to get four haircuts before being allowed to work out with the team.6 Pete Rose expressed his dissatisfaction with the rule by attending the 1972 winter meetings wearing a Vandyke beard.7 Rose asked Anderson, “Do you think Jesus Christ could hit a curveball?” When Anderson replied to the affirmative, Rose rebutted, “Not for the Cincinnati Reds he couldn’t – not with that beard.” 8

By 1970, other teams had copied the Reds’ dress code, including, paradoxically, the Oakland A’s. During the 1971 American League Championship Series, it was obvious that the Oakland right fielder was growing a mustache.9 Reginald Martinez Jackson was everything a baseball player was not supposed to be in 1971: university educated, outspoken, and articulate. Of mixed African American and Puerto Rican heritage, Reggie claimed that the New York Mets deliberately overlooked him in the 1966 amateur draft because he dated a “white” girl.10 He referred to himself in the third person and he stopped to watch his home runs before jogging gingerly around the bases. Now he was flouting the team rules with his mustache.

Reggie Jackson was hardly the first baseball player to grow a mustache. In the 19th century, they were commonplace. However, by 1913, when catcher Wally Schang wore a mustache as a member of the Philadelphia Athletics, it was considered an oddity by standards of that time.11 After Schang, attempts to grow mustaches and beards in the majors were scarce. The Washington Nationals signed former House of David pitcher Allen Benson to a contract in 1934, and he retained his beard.12 In 1936 outfielder Frenchy Bordagaray arrived at the Brooklyn Dodgers’ training camp sporting a goatee. Manager Casey Stengel was not impressed, insinuating that “if anyone is going to be a clown on this club, it’s going to be me.”13

In the postwar era, an anecdote shared by Tommy Davis was emblematic of the attitude toward facial hair among his peers. In 1966 he arrived in New York from the Dodgers wearing a Fu Manchu mustache. Davis was greeted by Mets teammates Jack Fisher and Ed Kranepool with a razor and shaving cream. Though Davis later grew a mustache, in 1966 he conceded, “Whoever heard of a ballplayer with a mustache?”14

Toward the end of the 1960s, Davis’s question was no longer rhetorical. Late in the 1968 season, the year before he was traded to the expansion Montreal Expos, Astros outfielder Rusty Staub grew a mustache. The manager in Houston was Harry Walker, an ardent traditionalist who “hated hippies and long hair.”15 According to John Wilson of the Houston Chronicle, “If Rusty had not grown that mustache, that … trade would [never] have been made.”16 In 1969 Dick Allen of the Philadelphia Phillies wore a mustache and an Afro during the regular season.17 He too was traded, to the St. Louis Cardinals. Jim Bouton grew a mustache one offseason but shaved, predicting, “What’s standing between me and my mustache is about twenty wins.”18

Despite their mod image, the 1971 Oakland A’s were otherwise no less conservative than any other team. Their owner, Charles O. Finley, proclaimed that “sweat plus sacrifice equals success.” His manager, Dick Williams, earned his reputation as a rigid disciplinarian with the Boston Red Sox. An insurance magnate based in Chicago, Finley imposed a dress code not only on his players, but also on the front-office staff. In 1972 Reggie arrived at spring training with a beard, much to the chagrin of his manager. Mike Hegan remembered:

“Charlie [Finley] didn’t like it … so he told Dick to tell Reggie to shave it off and Reggie told Dick what to do. This got to be a real sticking point.”19 As Williams remembered the situation, the other A’s players were becoming upset that Reggie was ignoring team protocol. Catfish Hunter, of all people, decided to take matters into his own hands aboard an early-season flight:

“Catfish walked to … where Charlie [Finley] was sitting,” recalled Williams in his autobiography. “‘Charlie,’ he announced, ‘Reggie Jackson has facial hair … and we don’t think it’s fair.’ ‘Oh really?’ he answered.”20 Using reverse psychology, he refused to reprimand Reggie and instead offered $300 to any player who grew a mustache by June 18.21 Father’s Day in Oakland was to become Mustache Day. 22

Anyone associated with the Oakland A’s was familiar with Charlie Finley’s penury. When the players were offered $300 merely for growing a mustache, most jumped at the occasion. Rollie Fingers grew a handlebar mustache that became his trademark – when his gross biweekly earnings were $1,200, how could he refuse a $300 bonus? As Fingers once told Phil Pepe, “For $300, I’d grow one on my rear end.”23 He even managed to negotiate for Finley to include $100 for mustache wax in his contract.24

Not all of the A’s were enthusiastic about the promotion, including Sal Bando:

“There were three guys that didn’t want to do it, Larry Brown, Mike Hegan, and myself. Finley called us in and convinced us … he wanted us to do it.”25 Hegan was the last holdout. “I finally grew a mustache, did it for about six weeks … and then shaved it off,” explaining that “my wife didn’t like it.”26 After a bitter contract negotiation with Finley, Vida Blue refused to engage. As Williams remembered, “The players were so confused by Charlie’s edict that most of them [also] decided to grow their hair long.”27 By Father’s Day, all the A’s except Vida wore a mustache. Mike Epstein grew muttonchops and a Fu Manchu mustache. Dave Duncan grew a beard. Even the coaching staff participated.

“I took the lineup card to the umpire and he said it didn’t look very good,” reported third-base coach Irv Noren. “It took a month or two to grow but $300 was $300 in 1972.” Along with the rest of the A’s, Noren returned from the game to find a check in his locker, though he admitted that “I shaved as soon as the check cleared.”

At a time when per-game attendance barely exceeded 11,000, the Oakland A’s sold 26,000 tickets to Mustache Day.28 In addition, fans wearing mustaches were admitted free. Several of the A’s besides Noren shaved immediately after the game, only to grow their mustaches back during the pennant drive. As Sal Bando explained, “We had success as a team so everybody stayed with it.”29

The Reds were favored to win the 1972 World Series. It was a close series that went the full seven games. Game Seven was tied, 1-1, after five innings. Gene Tenace, who had homered for Oakland twice in Game One, broke the deadlock with an RBI double off Pedro Borbón. Then Sal Bando drove in an insurance run with another double. With the score now 3-2, Rollie Fingers was called in from the bullpen for the ninth inning. When he enticed Pete Rose to fly out to left field for the third out, the Bikers had beaten the Boy Scouts.30 The A’s had established themselves as the pre-eminent team in the American League West, winning a division title each year from 1971 to 1975. Their prominence on the field, however, did not signify an instant eradication of dress codes elsewhere. Other teams retained their opposition, especially the Cincinnati Reds.

Despite playing barely .500, the Montreal Expos found themselves in an unexpected pennant race in 1973. General manager Jim Fanning acquired veteran outfielder Felipe Alou from the New York Yankees. As John McHale reminisced in 1993, “Now you have to understand that we did not allow mustaches on the team at that time. When Felipe arrived, he had this beautiful mustache. We didn’t know what to do and in this case, we decided to allow him to keep his mustache. By the time we were ready to tell him, he had already shaved in the clubhouse.”31

Ironically, the Expos were less charitable when younger players Steve Rogers, Tim Foli, and Dale Murray arrived at spring training with mustaches. Bob Dunn of the Montreal Star witnessed McHale’s reaction and compared it to “Louis Pasteur discovering a stream of bacteria loose in the lab.”32 Foli shaved grudgingly, arguing that he “wouldn’t want to take it to court but I probably could have.”33

Foli was referring to a controversy from 1973 involving Cincinnati outfielder Bobby Tolan. As the Reds fought the Los Angeles Dodgers for their division title, Tolan stopped shaving. Sparky Anderson ordered him to “shave or take off that uniform.”34 Tolan refused and was suspended for the rest of the season without pay.35 Then he filed a grievance through Marvin Miller and the Players Association. At the hearing, the union lawyer asked Anderson if he objected to Tolan’s Afro and his beard. The manager replied, “No, but he’s not wearing the uniform.”36 Tolan won the hearing and the Reds lost the pennant to the New York Mets. By December, both Tolan and Grimsley were traded to other teams.

The Oakland A’s won their third consecutive World Series in 1974, over the Los Angeles Dodgers. Owned by one Walter (O’Malley) and managed by another (Alston), the Dodgers allowed mustaches but not long hair or beards. So did the Yankees. From the time he purchased the Yankees in 1973, George Steinbrenner was paranoid about the image beards and long hair would convey to the public. At his first spring training with the Yankees, Lou Piniella remembered Steinbrenner barked at Bobby Murcer and Gene Michael to “put those caps on [and] look like Yankees – and you, Michael, get a haircut!”37 Bronx Bombers felt free to grow their hair long during Steinbrenner’s subsequent exile from baseball. When Steinbrenner returned in 1976, he was incensed about player photographs he saw in the team yearbook. Marty Appel was the director of public relations at the time:

“Look at this!” Steinbrenner screamed at Appel as he pointed at the players, “Hair’s too long! Hair’s too long! Hair’s too long! Hair’s too long! I can count twenty players with their hair too long in the photos you chose. Now I’m not saying that I’m putting you out on the street over this, but I am saying you better get it fixed.”38 Rather than affront Yankee tradition, Appel recalled the entire press run. The yearbooks were not reissued until June, thereby forfeiting two months of sales. Oscar Gamble joined the Yankees in 1976 wearing a legendary afro. Mindful of the Bobby Tolan grievance, team president Gabe Paul worried about how to approach Gamble to trim his afro. To Paul’s surprise, Gamble had no objection. Finding a barbershop open in Fort Lauderdale on a Sunday morning, on the other hand, was a far more difficult task.39 Reggie Jackson, Thurman Munson, Goose Gossage, Dave Winfield, and Don Mattingly were among the Yankees who attempted to test Steinbrenner’s patience by allowing their hair or beards to grow.

Many teams soon followed Oakland’s lead in reversing their dress codes. The Angels dropped theirs in 1974 when they hired Dick Williams. According to batboy Paul Hirsch, they could not impose one set of rules for the players and another for the manager.40 Steve Rogers and his teammates could grow beards however they wanted by 1977 as Williams left Orange County for greener pastures in Montreal. What if Dick Williams had managed Cincinnati instead? The Reds continued to be the most stubborn team on the issue of grooming standards. Meanwhile, as Sparky Anderson’s coaches received promotions to manage other teams, they took the Reds’ dress code with them.

In 1976 third-base coach Alex Grammas left Cincinnati to manage the Milwaukee Brewers. His new club featured several players with Fu Manchu mustaches, including Jim Colborn,

Darrell Porter, George Scott, Robin Yount, Gorman Thomas, Kurt Bevacqua, and Pete Broberg.41 All were required to shave under Grammas. A year later, Vern Rapp left the Reds to manage the St. Louis Cardinals. Asserting that he “didn’t come here to be liked,” Rapp drove a wedge against Al Hrabosky and Ted Simmons, when he prohibited mustaches and long hair.42 “The Mad Hungarian” was famous for his pitching antics and credited his intimidating presence to his Fu Manchu mustache. The long-haired Simmons was the player representative and with his support, Hrabosky threatened to file his own grievance. Hrabosky relented and shaved his mustache before posting a ghastly ERA of 4.38.43 Grammas was released in 1977 and Rapp barely lasted through April 1978.

Meanwhile, after nine years in Cincinnati, Sparky Anderson re-emerged in June 1979 to manage in Detroit. Already familiar with his feelings on facial hair; many Tigers shaved without being asked, including Reds alumnus Champ Summers.44 If Anderson banned mustaches on the Tigers, someone failed to notify Jason Thompson or Aurelio Rodriguez.45 Both players did not shave and were playing for different teams in 1980.

By the end of the 1970s, many of the attitudes viewed as radical or subversive a decade earlier were accepted as mainstream. To paraphrase Herb Tarlek from WKRP in Cincinnati, the battle between the dungarees and the suits had largely been won. Nobody bothered to alert the Reds that the white flags had been drawn. Only on February 2, 1999, when the Reds traded for outfielder Greg Vaughn to Cincinnati, was their facial hair ban repealed.

The 1972 World Series marked a turning point in the evolution of grooming standards in baseball. Facing the conservatively dressed Cincinnati Reds, the underdog Oakland A’s won a tightly fought seven-game Series wearing long hair, mustaches, and green and yellow polyester. As is the case with any form of social evolution, attitudes in baseball toward self-expression among the players did not change overnight. Opposition among managers and executives remained, particularly on the Reds, whose policy against facial hair remained intact until the final year of the 20th century. Did “the Mustache Gang” define the Oakland A’s players and if so, did they envision themselves as vanguards of change? Not if you asked Sal Bando, they did not. When interviewed on the subject, Captain Sal admitted that “we might have worn our hair longer and had mustaches but probably in today’s political climate most of us were conservative anyhow.”46 Perhaps the greatest legacy of the 1972 World Series was what transpired on the diamond 12 Octobers later. The San Diego Padres faced the Detroit Tigers in 1984, a World Series rematch between Dick Williams and Sparky Anderson. Many of the Padres players wore long hair and mustaches, as did several of the Tigers. And nobody noticed.

MAXWELL KATES, as a young collector, received a baseball card of Andy McGaffigan and remarked, “I think that’s the first time I’ve ever seen a Reds player with a moustache.” Thus began the genesis of “The Bikers Beat the Boy Scouts,” both as an article and as a lecture at SABR 44 in Houston. A chartered accountant who lives and works in midtown Toronto, he has attended games at 20 current ballparks, including Oakland — where he held the dubious distinction of running into Ray Fosse.

Acknowledgments

Jim Charlton, Dan Epstein, Paul Hirsch, Sean Lahman, Bruce Markusen, Scott Schliefer, Fred Taylor.

Sources

Appel, Marty, Now Pitching for the Yankees: Spinning the News for Mickey, Billy, and George (Toronto: Sport Media Publishing, 2001).

Bouton, Jim, Ball Four: The Final Pitch (North Egremont, Massachusetts: Bulldog Publishing Inc., 2000).

Epstein, Dan, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging ’70s. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010).

Gallagher, Danny, and Bill Young, Remembering the Montreal Expos (Toronto: Scoop Press, 2005).

Green, G. Michael, and Roger D. Launius. Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball’s Super Showman (New York: Walker Publishing Company Inc., 2010).

Hill, Art, I Don’t Care If I Never Come Back: A Baseball Fan and His Game (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980).

Jackson, Reggie, and Kevin Baker, Becoming Mr. October (New York: Random House LLC, 2013).

Kashatus, William, September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration. (State College, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2004).

Kates, Maxwell, “Alex Grammas,” in Mark Pattison and David Raglin, eds., Detroit Tigers 1984: What a Start! What a Finish! (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2012).

Markusen, Bruce, A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s (Haworth, New Jersey: St. Johann Press, 2002).

Miller, Marvin, A Whole Different Ball Game: The Sport and Business of Baseball (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1991).

Piniella, Lou, and Maury Allen, Sweet Lou (New York: Putnam Publishing Group, 1986).

Posnanski, Joe, The Machine: A Hot Team, a Legendary Season, and a Heart-Stopping World Series – the 1975 Cincinnati Reds (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2009).

Reston, James, Collision at Home Plate: The Lives of Pete Rose and Bart Giamatti (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1991).

Robertson, John, Rusty Staub of the Expos (Scarborough, Ontario: Prentice-Hall of Canada Ltd., 1971).

Williams, Dick, and Bill Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life of Hardball (Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990).

Daugherty, Paul, “Reds Keeping Stiff Upper Lip,” Toledo Blade, March 10, 1992: 15.

Goldstein, Richard, “Frenchy Bordagaray is Dead; The Colorful Dodger was 90,” New York Times, May 23, 2000).

Grayson, Harry, “Wally Schang, One of Catching Greats, In Six Fall Series,” Evening Independent, September 18, 1943, 10.

Kay, Joe, “Reds Lift Ban on Facial Hair,” Bryan (Ohio) Times, February 16, 1999, 13.

Pepe, Phil, “Fingers, Reds Losers in Mustache Dispute,” Ottawa Citizen, March 26, 1986, B2.

Tarantino, Anthony, “Hair Affairs,” San Diego Union-Tribune, April 24, 2006.

“Maury Means Pirate Flag, Says Ex-Teammate Tommy Davis,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 20, 1966, 11.

“Allen Benson,” Washington Senators Press Photo, 1950.

Notes

1 Bruce Markusen, A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s, 171-172.

2 Markusen, 172.

3 Daugherty, 15.

4 Joe Posnanski, The Machine: A Hot Team, a Legendary Season, and a Heart-Stopping World Series – the 1975 Cincinnati Reds, 60.

5 Posnanski, 60.

6 Dan Epstein, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging ’70s, 174.

7James Reston, Collision at Home Plate: The Lives of Pete Rose and Bart Giamatti, photo insert.

8 Posnanski, 115-116.

9 Markusen, 85.

10 Reggie Jackson and Kevin Baker, Becoming Mr. October, 9. The “white girl” referred to, Jennie Campos Jackson, was actually a light-skinned Mexican American of Mestizo ancestry).

11 Harry Grayson, “Wally Schang, One of Catching Greats, In Six Fall Series,” The Evening Independent, September 18, 1943, 10.

12 “Allen Benson,” Washington Senators Press Photo, 1950.

13 Richard Goldstein, “Frenchy Bordagaray is Dead; The Colorful Dodger was 90,” New York Times, May 23, 2000.

14 “Maury Means Pirate Flag, Says Ex-Teammate Tommy Davis,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 20, 1966, 11.

15 John Robertson, Rusty Staub of the Expos, 18.

16 Robertson, 18.

17 William Kashatus, September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration, cover.

18 Jim Bouton, Ball Four: The Final Pitch, 20.

19 Markusen, 85.

20 Dick Williams and Bill Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life of Hardball, 136-137.

21 Williams, 137.

22 Williams, 137.

23 Phil Pepe, “Fingers, Reds Losers in Moustache Dispute,” Ottawa Citizen, March 26, 1986, B2.

24 Markusen, 102.

25 Markusen, 101.

26 Markusen, 101.

27 Williams, 137.

28 Epstein, 173.

29 Markusen, 101.

30 Markusen, 171.

31 John McHale’s speech at the Montreal Expos’ 25th-anniversary gala dinner, January 14, 1993.

32 Danny Gallagher and Bill Young, Remembering the Montreal Expos, 42.

33 Gallagher, 43.

34 Daugherty, 15.

35 Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ball Game: The Sport and Business of Baseball , 241.

36 Daugherty, 15.

37 Lou Piniella and Maury Allen, Sweet Lou, back cover.

38 Marty Appel, Now Pitching for the Yankees: Spinning the News for Mickey, Billy, and George, 235-236.

39 Appel, 181-182.

40 Correspondence with Paul Hirsch, January 18, 2014.

41 Maxwell Kates, “Alex Grammas,” in Mark Pattison and David Raglin, eds., Detroit Tigers 1984: What a Start! What a Finish!, 201.

42 Epstein, 176.

43 Epstein, 176.

44 Art Hill, I Don’t Care If I Never Come Back: A Baseball Fan and His Game, 190.

45 Hill, 191.

46 Markusen, 172.