The Colonel and Hug: The Odd Couple … Not Really

This article was written by Steve Steinberg - Lyle Spatz

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

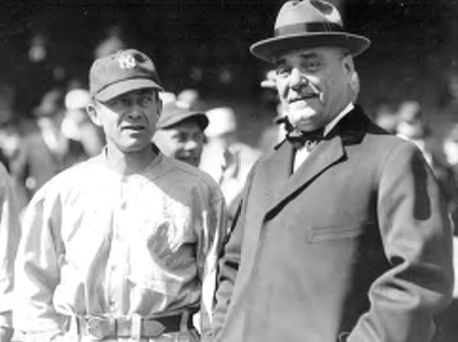

Although on the surface Miller Huggins and Jacob Ruppert seemed worlds apart, the two men had striking similarities. They were the architects of the New York Yankees’ dominance in the 1920s. (BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY)

Jacob Ruppert believed that hiring Miller Huggins as his manager after the 1917 season was the first and most important step in turning the Yankees from also-rans into champions. Under Ruppert’s ownership and Huggins’s leadership, the Yankees would dominate the decade of the 1920s, winning six pennants and three World Series.

At first glance, the two could not have been more different. Ruppert, an urbane New Yorker, was a man of great wealth, which he used freely to indulge himself. He had a mansion on Fifth Avenue, a country estate, and a 113-foot yacht. He raced and bred horses and dogs, and he collected rare books, art, and jade pieces. He also was a meticulous dresser. “He commonly carries a serious expression,” wrote Damon Runyon. “He wears clothes of the latest cut, is very particular about his apparel, but never deviates from snowy white linen shirts and collars.”1

Pitcher Waite Hoyt said of Ruppert, “His Rolls Royce always looked brand new when it was 10 years old. He was that way about everything.”2 Author Jack Moore wrote, “In many ways he belonged to the world of New York society that Edith Wharton described so beautifully and devastatingly in her novels. … He relished the title [Colonel] and conducted his affairs with the Yankees as though he were their general.”3

Huggins, a no-nonsense Midwesterner, had little interest in what others thought of him, and certainly not what they thought of his appearance. He had no extravagances. His greatest joy came from fishing, smoking his pipe, and golf, which he started playing late in life.

These differences came close to dooming the Ruppert-Huggins collaboration at the start, according to Sporting News publisher J. G. Taylor Spink’s description of their first meeting. “Coupled with his gnome-like appearance, the cap accentuated his midget stature, and made Huggins look like an unemployed jockey. And Colonel Ruppert, an immaculate dresser, instinctively shied away from a cap-wearing job applicant.”4

Ruppert, especially as a younger man, was a partygoer and a member of many social clubs. As a congressman, he was a regular at White House receptions, held by his fellow New Yorker Teddy Roosevelt. Home in New York, he would often dine in one of the city’s better restaurants, like Delmonico’s, and then spend the evening socializing at the Lambs Club, the New York Athletic Club, or one of the several German societies to which he belonged.

He was also a risk-taker, especially when it came to fast cars. In 1902, he and fellow congressman Oliver Belmont were arrested in Washington for driving almost 20 miles per hour, well above the posted speed limit.5 Ten years later, Ruppert was racing his motorcycle against a garage owner driving a car. When the car slammed into a tree, the driver was killed.6

Huggins’s typical evening was spent at home with his sister, Myrtle, with whom he lived. And the only time he may have been seen in a car that was going too fast, it would have been as a passenger. He would sometimes ride along with Babe Ruth, another fast and risky driver.

Yet, in the more important matter of building winning baseball teams, Ruppert and Huggins were surprisingly alike.

1. Both had been reared by strict fathers, who had attempted to dictate their careers. Ruppert’s father had been more successful at it, dismissing his son’s early dreams of being a baseball player and later, his plan to enter West Point. “My dad, who was a brewer, said, ‘This West Point stuff, this ball playing business, is all nonsense. You go into the brewery.’”7

Huggins was less the obedient son. “The head of our family,” recalled his sister Myrtle, “was a strict Methodist who abhorred frivolity and listed baseball as such, especially baseball played on Sunday.”8 Huggins became a ball player in spite of his father’s wishes, usually under an assumed name when he began playing as a semiprofessional. And on those evenings spent at home with Myrtle, he would sometimes have a glass of wine, something which his father would have frowned on.

2. By nature, both Ruppert and Huggins were intensely private men—aloof, blunt, and not interested in their personal popularity. “Despite the fact that he is one of the smartest men that ever trod on a ball field, and is a lawyer in the bargain,” wrote a New York Sun columnist about Huggins, “he does not seem to realize what assets popularity and publicity can be to a successful manager.”9

It was much the same with Ruppert: He was a “regal mystery” said one reporter. “There was about him a reserve that made such a [close] relationship difficult.”10 The Colonel “was not one to pal around with the boys,” Rud Rennie wrote in the New York Herald-Tribune. “For the most part, he was aloof and brusque.”11 Even his fellow owners found him distant.

3. Neither man was “colorful,” someone reporters could rely on to do or say something provocative. Huggins had no more personality, wrote one New York reporter, “than a stark old oak tree against a gray winter sky.”12 Ruppert also had a bland personality. A 1934 editorial in Baseball Magazine noted, “The genial Colonel has never cared overmuch for the spotlight. … He is, first and foremost, a businessman, and showmanship is not his forte.”13

4. Both were lonely men. Damon Runyon wrote, “Huggins always struck me as rather a pathetic figure in many ways early in his managerial career. He was inconspicuous in size and personality. He seemed to be a solitary chap, with few intimates. He wasn’t much of a mixer. … But the little man ‘had something,’ no doubt of that.”14

Ruppert, too, was lonely. “He was a simple man, and direct, but he had moments of loneliness,” explained George W. Sutton Jr., who handled public relations for him. “Sometimes when he was busy he would stop and ask me about my farm, and talk like that until something turned him back into the business machine.”15

5. Being bachelors only added to their loneliness, though they had different views on marriage. Huggins told Dan Daniel, “That’s my one big regret. Married life gives a man varied interests.”16

When he was younger, Ruppert said he did not want to marry because “it was too much fun being single.”17 He later said, “There are too many attractive girls in New York to ever allow a man to be lonesome.”18

As an older man, he became close to Helen Weyant, a woman who became the informal hostess at his upstate mansion. She was much younger than Ruppert, and there is no evidence of a romantic relationship between them, or between Ruppert and any woman. He was more like a kindly old uncle; so kindly, he left Weyant a third of his estate.

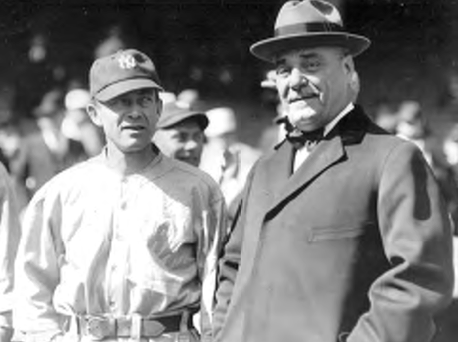

Ed Barrow, seen at right with Ruppert (left) and Huggins, Barrow was a Yankees front office fixture from 1921 to 1945.

6. While Ruppert was a fan the Yankees, he still treated them as a business. “If a machine in my business wears out I replace it,” he said. “I am always looking at improved machines; improved property. I study efficiency in business. Baseball is a sport; it is a hobby, but it is a business. I want the most out of baseball.”19

Yet a similar quotation from Huggins could easily be mistaken for something Ruppert said. Operating a ball club, he believed, was “the quality of being able to look ahead and size up the future by the signs of the present. … In a way this business instinct is nothing but a keen gambling sense. It is knowing when to throw a lot of new capital into the organization.”20

7. Having control of their “business” was key to both men. To the extent possible, they wanted to control their own destinies. Ruppert couldn’t coexist with his partner, Til Huston. Ed Barrow described them as “two self-willed personalities, who by background, manner, and outlook were worlds apart.”21 Likewise, Huggins couldn’t coexist with Branch Rickey. When Rickey became his boss in St. Louis, after the 1917 season, he knew all personnel decisions would be made by Rickey and left the Cardinals for the Yankees.

8. The Colonel and “Hug” were excellent judges of personnel, who looked for the same personality traits in potential hires, which were a man’s disposition and his belief in putting the team first. Ruppert’s key hires were brilliant. In addition to Huggins, he brought in Ed Barrow as his business manager, Joe McCarthy as a successor to Huggins, and George Weiss to develop and run the farm system.22

Few men Huggins traded away went on to star elsewhere. No less an authority than John McGraw had said back in 1915, “Miller Huggins is my ideal of a real leader. … He can take a player who has shown only a mediocre supply of ability on some team and transform him into a star with his club.”23

9. Dealing with Babe Ruth’s often childish and outrageous behavior caused trials and tribulations for both, particularly Huggins. Eventually, they each would have to confront the Babe, and each would come out on top.

Ruth had repeatedly ignored his manager and violated club rules for years. In 1925, with the Yankees and the Babe in deep slumps (they were 27 games out of first place, and he was batting .266), Huggins decided it was a good time for him to crack down. With Ruppert’s backing, he suspended Ruth for two weeks and fined him $5,000. The following season, Ruth and the Yankees made stunning comebacks. The Babe led the New Yorkers to the first of three consecutive pennants, leading the league in runs, runs batted in, and the first of six consecutive home run crowns.

The ultimate Ruppert-Ruth confrontation came ten years later, in 1935. Ruppert had repeatedly refused Ruth’s request to manage the club. With the 39-year-old Babe’s aging body and on-field performance breaking down, Ruppert declared it was time for the Yankees to move on. “The success of the Yankees is no longer intertwined with, and dependent upon, the success of Ruth,” he said.24

Despite the headaches he gave them, Ruppert and Huggins benefited greatly from having Ruth on their team. He not only led them to success on the field, his popularity had helped them take away a good portion of New York’s fans from John McGraw’s Giants.

“Up to a couple of years ago, the Yanks were just the ‘other New York team.’ But the immense personal popularity of Babe Ruth and the dynamite in the rest of that Yankee batting order have made the Yanks popular with the element that loves the spectacular,” wrote Sid Mercer.25

10. Both Ruppert and Huggins understood the demands of owning and managing a team in New York. The New York fans and press were no different than they are today. Keeping them happy was a constant battle, something both men understood. “The psychology of New York is entirely different. … You’ve got to make good!” Huggins said.26 “The whole trouble is that we [the Yankees and the Giants] are New York clubs,” he said. “If we were located in Kankakee things would be different. … ‘Beat New York’ is the slogan of the land, and when it can’t be done, the boys start slinging mud.”27

“This is one city where the public demands a winner, but you can’t palm off inferior goods on them,” Ruppert had said as early as 1918.28 “Yankee fans want a winning ball club,” he explained a decade later. “They won’t support a loser.”29

11. Both men had a fierce will to win. When Huggins was a young player on the Reds, Ned Hanlon, who had managed the legendary, win-at-all-costs Baltimore Orioles of the 1890s, said of his attitude (and that of one of his teammates), “The game is everything to them. Victories make them feel as though they owned the earth; defeat makes them angry.”30

As the manager of the Yankees, Huggins said, “It is our desire to have a pennant winner each year indefinitely. New York fans want championship ball, and the Yankees can be counted on to provide it.”31

Ruppert’s approach was no different. “I want to win the pennant five more years in a row if we can. We are going ahead to get any good ball player we can. Winning pennants is the business of the New York Yankees.”32 Ruppert said, “Huggins was never content. He always felt that no matter how strong the Yankees were, they could be just a little stronger.”33

Just before he died, Ruppert revealed the winning formula. “Money alone does not bring success. You must also have brains, organization, and enterprise. Then you’ve got something.”34

12. Because of their intense desire to win, the difficulties of staying on top haunted Ruppert and Huggins, as they agonized over the Yankees’ success. W. O. McGeehan said of Ruppert, “The Colonel has an infinite capacity for mental anguish and likes to do his worrying early.”35 Ruppert said in early 1928, “A slide, a broken leg, and the finest ball player may jump into baseball oblivion. That has happened before; it may happen again. We must have replacements.”36

The 1927 Yankees had swept the World Series in four games and were already being talked about as the greatest team ever. Yet sportswriter Walter Trumbull observed at the baseball meetings that winter, “The case of Miller Huggins is almost pathetic. He is trying desperately to build up the Yankees. That is a tough job, a little perhaps, like trying to add a bit of height to Mount Everest.”37

Despite cries from around the league to break up the Yankees, both men recognized the difficulties of staying on top. Ruppert’s response to the other owners was to build up their teams, not tear down his. He compared running the team to keeping his brewery on top, where if a part or a machine broke down, he replaced it.

Huggins’s response to the “Break up the Yankees” crowd was more philosophical. In 1928, after the Yankees had again swept the Series, Huggins sounded an alarm. “Time will take care of the Yankees, as it takes care of everything else. This team, powerful as it is, will crack and break, no matter what any of us does to keep it up. The history of all great teams and all great personal fortunes is the same. They dominate the scene for a while but they don’t last. Great teams fall apart and have to be put together again.”38

Babe Ruth, right, battled fiercely with Ruppert and Huggins over the years. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

13. Each had faced substantial obstacles along the way, Huggins on the field and Ruppert with his brewery and with challenges to his ownership of the Yankees. Huggins had to deal with repeated challenges to his authority, beginning in 1913, when he took over as manager of the Cardinals. A 1922 Sporting News editorial noted, “Perhaps never in the history of the game has a manager been so flouted, reviled, and ridiculed.”39

Prohibition robbed Ruppert of his primary source of income with the brewery. And he had to take on (and take down) the president of his league, Ban Johnson, and then his co-owner, Til Huston.

14. Baseball meant the world to the two lonely bachelors and brought meaning to their lives. Ruppert told Taylor Spink in 1937, “It seems to me I never have got around to doing the things I wanted to do most. For example, when I was a youngster, I wanted to be a ball player.” He also said, “I was never able to be a major league catcher. That was my boyhood ambition.”40

In 1918, three years after purchasing the Yankees, Ruppert wrote, “I have got a lot of excitement out of this magnate business and no doubt there is much more coming to me before I am through.”41 After acquiring Ruth, Ruppert told the press that it was his “life purpose” to give New York a championship team.42 And in 1923, “Here I am deeper than ever in baseball and more in love with the game than ever.”43

Damon Runyon wrote after the 1923 championship season, “The possession of great wealth is an old story to him. There was no novelty for him, no thrill, in the buying excesses of great wealth. It was the thing that money couldn’t buy that brought him his big, bright hour.”44

Huggins once said, “I fell in love. … The object of my love, though, was no lady. It was baseball.”45 He had little outside of baseball in his life. On off days during the season, he would often go to the Yankees’ offices downtown. “Baseball is my life. I’d be lost without it. Maybe, as you say, it will get me some day—but as long as I die in harness, I’ll be happy.”46 And of course it did get him, and he did die in harness.

Unlike Ruppert, Huggins did not want recognition. Christy Walsh said, “He played his part on the ball field without giving a thought to the grandstand or the critics. As for publicity, he loathed it almost as much as he belittled so-called personal popularity.”47 Even Walsh, Huggins’s agent, said: “You know him intimately, and you don’t know him at all.”48

Ruppert told sportswriter Sid Mercer: “Take it from me, Sid, money is only a burden after you have enough for a comfortable living. It becomes a responsibility. … Here I am trying to snatch a few days with my ball team and I’ll bet you I’ll have to cut my vacation short.”49

15. Sometimes, when the pressure of managing in New York became overwhelming, Huggins would reflect on his earliest days in baseball. “I probably had the most fun in my baseball career when I captained the Fleischmann Mountaineers. … That was a joy ride that year—1900—we won about 60 out of 66 games.”50 Bob Connery, a lifelong friend who scouted for Huggins in St. Louis, said said, “Those five years with the Cardinals were happier than any five years in New York, even when Huggins was winning pennants.”51

Ruppert also longed for some of the simpler pleasures of the game, denied him by his position. He lamented to Taylor Spink in 1937, “I could not buy the liberty and the freedom of the youngster who could barely spare 50 cents that got him into the bleachers. That’s money, and that’s responsibility for you.”52

16. These were men of impeccable integrity. During the Black Sox scandal, Ruppert promised that, “for my life and yours, baseball will be kept clean.”53 Damon Runyon once wrote, “I believe Colonel Ruppert would sacrifice his entire baseball investment rather than knowingly be a party to an unsportsmanlike action.”54

His reaction to the Yankees’ sweep of the 1927 World Series sweep is instructive. “I am happier in what I believe is a great thing for baseball,” he said. “It will cost us something like $200,000, but there can be no talk now of stringing a series out. We wanted to win in four straight games and we did, because we have a wonderful team.”55

Huggins established his reputation for decency at the outset of his professional career. When St. Paul Saints owner George Lennon sold Huggins to the Cincinnati Reds, he told reporters, “He is a finer man than he is a ballplayer.”56

Along with integrity, both had a sense of duty to take care of people. Ruppert’s aide, George Perry wrote, “He was a hard-boiled man to some, but they judged him entirely from externals. The charity he gave never will be known. He never sought publicity that way.”57

During the days of the Federal League war, when St. Louis had three Major League teams and the Cardinals’ finances were shaky, Huggins covered the team’s payroll out of his own pocket. The Sporting News wrote in an editorial, “He [Huggins] was all there was to the club, practically under petticoat management even to the extent of being its financial savior.”58

17. Moreover, Ruppert and Huggins were fiercely loyal to and trusting of one another. After the 1922 World Series, the Yankees’ second consecutive Series loss to the Giants, the press again was calling for Ruppert to replace Huggins. But the colonel remained steadfast; he re-signed Huggins and said, “Maybe these people who are firing him and hiring others know more about it than I do. … This talk is ridiculous. We are for Huggins, first, last and all the time.”59 A year later, Huggins rewarded him with the Yankees’ first world championship.

Then in the disastrous summer of 1925, with Yankees on their way to a seventh-place finish, Ruppert said, “It would be shabby treatment to remove him now or at any other time. … Huggins can remain in control of my team as long as he feels like it.”60

After the 1924 season, Huggins declared, “Ruppert is a wonderful man to work with. After seven years of close association I guess two men get to understand each other pretty well. If I really want a man, he will go the limit to get him. And he never tires of winners.”61

18. Additionally, both men were visionaries. Ruppert saw the potential of Sunday baseball, building Yankee Stadium, and building up the farm system, but he was by no means perfect: he lagged in the areas of integration, night baseball, and the radio broadcasts of games.

Huggins, who had been a quintessential deadball-type player, foresaw the coming of the longball era and urged Ruppert to acquire Ruth.

Though seemingly very different, together the shared legacy of Jacob Ruppert and Miller Huggins was the establishment of an enduring winning franchise, a dynasty that lived long after they were gone. “Getting him was the first and most important step we took toward making the Yankees champions,” Ruppert said. “Him” was not Babe Ruth, but rather Miller Huggins.62

Sportswriter Warren Brown wrote: “We never have run across anyone else who stressed winning as much as Col. Jake Ruppert.”63 “Winning was a mania with him,” wrote Sid Mercer after Ruppert’s death.64

“The combination of brains and money,” wrote F. C. Lane of the two New York clubs (also John McGraw’s Giants), “is a hard pair to beat. … The attempt to divorce wealth and intelligence from all advantage has never succeeded anywhere.”65

Rupert and Huggins would have one more thing in common: perhaps fittingly, both would be long overlooked for formal recognition, which in baseball means election to the Hall of Fame. Huggins did not reach Cooperstown until 1964 and Ruppert not until 2013.

STEVE STEINBERG and LYLE SPATZ are the co-authors of “The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees,” the stories of Jacob Ruppert and Miller Huggins and how, a century ago, they laid the foundation for the future Yankees’ greatness. Steve’s and Lyle’s previous collaboration, “1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York,” was awarded the 2011 Seymour Medal. Steve has also written “Baseball in St. Louis, 1900–1925” and many articles revolving around early twentieth-century baseball, including a dozen for SABR publications. He has been a regular presenter at SABR national conventions. Lyle has recently published “Willie Keeler: From the Playgrounds of Brooklyn to the Hall of Fame.” He has also written biographies of Bill Dahlen and Dixie Walker, among other books, and has edited books on the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers and the 1947 New York Yankees.

Notes

1. Damon Runyon, New York American, December 27, 1924.

2. Eugene Murdock, Baseball Players and their Times: Oral Histories of the Game (Westport, CT: Meckler Publishing, 1991), 41.

3. Jack B. Moore, Joe DiMaggio: A Bio-Bibliography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1986), 37.

4. Spink’s account appeared years later in “Looping the Loops,” Sporting News, October 21, 1943. Spink was not present at the meeting but probably received firsthand accounts from both Ruppert and Huggins.

5. “O. H. P. Belmont, Too Speedy, Arrested,” New York Herald, March 26, 1902.

6. “John Gernon Killed Racing Mr. Ruppert,” New York Herald, June 29, 1912.

7. J. G. Taylor Spink, “Three and One,” The Sporting News, August 19, 1937.

8. Myrtle Huggins, as told to John B. Kennedy, “Mighty Midget.” Collier’s, May 24, 1930, 18. Years later, James Huggins became reconciled to his son’s playing baseball and even bragged that the skill he showed was hereditary. Henry F. Pringle, “A Small Package,” New Yorker, October 8, 1927, 25.

9. Shortstop, “Huggins Fails to Snare Popularity,” New York Sun, June 15,1919.

10.Frank Graham, The New York Yankees (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 248.

11.Richard Tofel, A Legend in the Making: The New York Yankees in 1939 (Chicago: Ivan R, Dee, 2003), 8.

12.Hyatt Daab, “Timely News and Views in the World of Sport,” New York Evening Telegram, October 26, 1920.

13.Editorial, Baseball Magazine, March 1934, 434.

14.Damon Runyon, “Between You and Me,” New York American, September 27, 1929.

15.“New Owners of Yanks Recover Enough to Talk,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 22, 1939.

16.Dan Daniel, “Late Chief’s Policies to Govern New Yank Pilot,” New York Evening Telegram, September 27, 1929. Daniel revealed these comments only after Huggins’s death.

17.Fred Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1996), 228.

18.Betty Kirk, “Jacob Ruppert, ‘Born Bachelor,’ Sees Day Coming with Marriage Extinct,” New York Evening Telegram, June 13, 1928.

19.Frank F. O’Neill, “Loud Wails in Wake of Yank Deal,” New York Evening Journal, January 6, 1928.

20.Will Wedge, “Business Instinct in Baseball,” New York Sun, April 17, 1926.

21.Edward G. Barrow, with James M. Kahn, My Fifty Years in Baseball (New York: Cowan-McCann, 1951), 123.

22.Former Yankees pitcher Bob Shawkey was Huggins’s immediate successor, but Ruppert replaced him after one season.

23.“Hug May Capture Pennant, but not in 1915—Says McGraw,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 23, 1915.

24.Dan Daniel, “Ruppert Sees Boom Year and Pennant for Yanks,” New York Evening Telegram, undated article in Jacob Ruppert file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and Archives.

25.Sid Mercer, “Whole City Busy with ‘Dope,’” New York Evening Journal, October 3, 1921.

26.Miller Huggins, “Serial Story of his Baseball Career: Getting New York Angle Huggins’ Biggest Problem at Start of Managership,” Chapter 50, San Francisco Chronicle, March 11, 1924.

27.Joseph Gordon, “Yankee Pilot Waxes Furious at Accusation,” New York American, December 16, 1927.

28. Jacob Ruppert, “Building a Winning Club in New York: An Interview with Col. Jacob Ruppert,” Baseball Magazine, June 1918, 253.

29. Rud Rennie, “Stop Squawking!” Collier’s, March 4, 1939, 11.

30. Ned Hanlon, “Jake [Weimer] and Little Hug are Shining Examples,” Cincinnati Times-Star, April 30, 1906.

31. Miller Huggins, The Sporting News, August 4, 1927.

32. Frank F. O’Neill, “Loud Wails in Wake of Yank Deal,” New York Evening Journal, January 6, 1928.

33. Frederick G. Lieb, “Ruppert Praises Word of Huggins,” New York Evening Telegram, September 21, 1923.

34. Rud Rennie, “Stop Squawking!” 61.

35. W. O. McGeehan, “Down the Line,” New York Herald Tribune, March 11, 1925.

36. Frank F. O’Neill, “Loud Wails in Wake of Yank Deal,” New York Evening Journal, January 6, 1928.

37. Walter Trumbull, “The Listening Post,” New York Evening Post, December 13, 1927.

38. Joe Vila, “Setting the Pace,” New York Sun, December 26, 1928.

39. Editorial, The Sporting News, October 26, 1922.

40. J. G. Taylor Spink, “Three and One,” The Sporting News, August 19, 1937.

41. Jacob Ruppert, “Building a Winning Club in New York,” 254.

42. “Ruth Bought by New York Americans for $125,000, Highest Price in Baseball’s Annals,” The New York Times, January 6, 1920.

43. W. O. McGeehan, “Ruppert Lives to Learn Baseball Men Have Class,” The Sporting News, December 27, 1923.

44. Damon Runyon, “Deserved Tribute to Colonel Ruppert,” The 1924 Reach Official American League Guide, 243.

45. Miller Huggins, “How I Got that Way,” New York Evening Post, October 2, 1926.

46. Ford Frick, “Huggins Born 49 Years Ago, Starred with Cardinals,” New York Evening Journal, September 25, 1929.

47. Christy Walsh, South Bend [Indiana] News-Times, September 1929, exact date not known.

48. Warren Brown, “So They Tell Me,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, September 27, 1929.

49. Sid Mercer, “The Colonel,” New York Journal-American, January 17, 1939.

50. Miller Huggins, “Huggins Wins his Sixth Flag,” New York Sun, September 29, 1928. Future Major League stars on the Fleischmann Mountaineers team included Doc White and Red Dooin.

51. Fred Lieb, The St. Louis Cardinals (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 69.

52. J. G. Taylor Spink, “Three and One,” The Sporting News, August 19, 1937.

53. William L. Chenery, “Foul Ball!” The New York Times, October 3, 1920.

54. Damon Runyon, “Runyon Says,” New York American, December 27, 1924.

55. “Ruppert Happy, Though Smile Cost $200,000 in Receipts,” The New York Times, October 9, 1927.

56. Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, “Huggins Got $1,000 of Purchase Money,” March 8, 1904.

57. George Perry, “Three and One: Looking Them Over with J. G. Taylor Spink,” The Sporting News, March 2, 1939.

58. “The Change Huggins Makes,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1917.

59. John Kieran, “Huggins Will Manage Yanks Next Season, Says Club Owner,” New York Herald Tribune, October 10, 1922.

60. Joe Vila, “Ruth May Pay Heavy Penalty for Getting Back too Quickly,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1925.

61. Frederick G. Lieb, “Huggins Will Stay with Yanks Indefinitely; No Longer has Any Thought of Retiring,” New York Telegram and Evening Mail,” December 26, 1924.

62. Jacob Ruppert, “The Ten Million Dollar Toy.” Saturday Evening Post, March 28, 1931, 18.

63. Warren Brown, “All in a Week,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, January 15, 1939.

64. Sid Mercer, “The Colonel: Victory Always his Aim,” New York Journal-American, January 20, 1939.

65. F. C. Lane, “The Shadow of New York on the Baseball Diamond,” Baseball Magazine, August 1923, 398.