The Composition of Kings: The Monroe Monarchs and the Negro Southern League, 1932

This article was written by Thomas Aiello

This article was published in 2006 Baseball Research Journal

When Negro National League officials agreed to close operations for 1932 due to the hard realities of the Great Depression, the usually minor Negro Southern League and the newly created East-West Colored League became black baseball’s “major leagues.” Low attendance figures, disillusionment with the National League collapse, doubts about the ability of the leagues to complete a season, and the complications of player trade disputes led to a muddled portrait of black baseball in 1932. The collapse of the East-West in early July didn’t help. The cumulative result was an historiographical lapse in coverage of black baseball in 1932. But baseball happened in the black communities that year—baseball with important consequences for the development of the Negro Leagues—and one of the year’s most relevant teams was the Monroe Monarchs.

Monroe was in the northeast corner of Louisiana, the hub of a poor cotton-farming region in the Mississippi Delta approximately 70 miles from the river and 40 from the Arkansas border.1 Its 10,112 African Americans constituted 38.9% of the city’s 26,028 residents. Almost 43% of the black population was out of work, and almost 17% were unable to read. 19,041 of Ouachita Parish’s 54,337 were black. Of those, close to 10,000 were gainfully employed and slightly more than 3,000 were illiterate.2 In 1919, Monroe earned the moniker “lynch law center of Louisiana,” and from the turn of the century to the close of 1918, the region witnessed 30 lynchings.3 As Michael Lomax demonstrated in his study of 19th-century black baseball entrepreneurship, the Negro Leagues as a “unifying element” of a community is so common and self- evident a conclusion that it lacks any tangible edifying power.4 Monroe’s situation, however, served as a paradigmatic example of the need for this “unifying element.” And unlike many small town baseball teams, the Monarchs’ impact extended far beyond Monroe’s city limits.

Fred Stovall wanted his Monarchs to be part of a new league in 1932 rather than the 1931 Texas League, which his team won. A white Dallas native, Stovall came to Monroe in 1917, and by 1932 owned both the Stovall Drilling Company and the J. M. Supply Company, among other enterprises, allowing him to found his black baseball team in 1930 with drilling employees. He never incorporated the team, even after its success led him to hire veteran professionals. Even before the pros arrived, however, Stovall built his team—and the larger black community, many of whom he employed at his various businesses—Casino Park, which included not only a ball field but a swimming pool and dance pavilion. Historian Robert Peterson echoes contemporary reports that the erection of the stadium was largely the product of generosity. (Of course, Stovall was a businessman, and the entry fees of 25 and 50 cents demonstrated that profit was also a motive.)5

Through a series of negotiations, Stovall maneuvered his team into the newly formed Negro Southern League for 1932, with a far more prestigious roster of teams than Monroe had ever faced. The Atlanta Black Crackers, Birmingham Black Barons, Memphis Red Sox, Montgomery Grey Sox, Little Rock Greys, and Nashville Elite Giants were joined by newcomers the Indianapolis ABCs, Louisville Black Caps, and Chicago American Giants (under the new ownership of Robert A. Cole), along with the Monarchs.6

The Monarchs acquitted themselves well the first half of the season. They were 33–7 on the Fourth of July. Chicago’s 30–9 record kept them slightly behind the Monarchs. “All is not well in the Southern League,” the Chicago Defender reported. League President Reuben B. Jackson issued a ruling at the close of the first-half schedule that, due to its use of players claimed by other teams, two Memphis Red Sox games against Cole’s American Giants would be forfeited. Rather than nullifying the outcomes, however, Jackson ruled the games to be Chicago wins. The controversial decision gave Chicago the first-half pennant.7

The Louisiana Weekly acknowledged the league ruling on the games, but declared Monroe the victor anyway. The paper’s coverage noted the protests mailed to the league office by Monroe fans, arguing that the NSL attempted “to give the Chicago nine something they have not rightfully won. All the southern papers as well as some of the northern and eastern papers carry the standing just as it is with Monroe leading and naturally, the fans are not fooled.”8

Various reports of the first-half standings led to uncertainty. The Defender’s first half standings gave Chicago first place with a 34–7 record, while Monroe was 33–7.9 The Morning World reported that the Monarchs’ record trumped Chicago’s 28–9.10 As of mid-August, the remainder of the Southern League season seemed in doubt, with Monroe (according to the Defender) not playing any league games, and Chicago canceling a scheduled trip to Memphis. Montgomery, Atlanta, Little Rock, and Birmingham had already abandoned league play.11

In this confused state, Nashville took the second-half pennant. Although Chicago and Nashville began referring to the NSL championship as the only championship, the Pittsburgh Crawfords (who played games against the East-West and the Southern, not officially joining either in 1932) scheduled a series with the Monroe Monarchs billed in most black weeklies as the “World Series.”12 The season had been as beneficial for the Crawfords as it had for the Monarchs. Gus Greenlee, the team’s owner, took the opportunity created by the financial destitution of the leagues to lure the best players from its Pittsburgh rival, the Homestead Grays. The Crawfords moved from beneath the shadow of Cumberland Posey’s Grays to become a premier team in their own right. When playing at home, the Crawfords played in the newly opened Greenlee Park, which held 6,000 fans.13

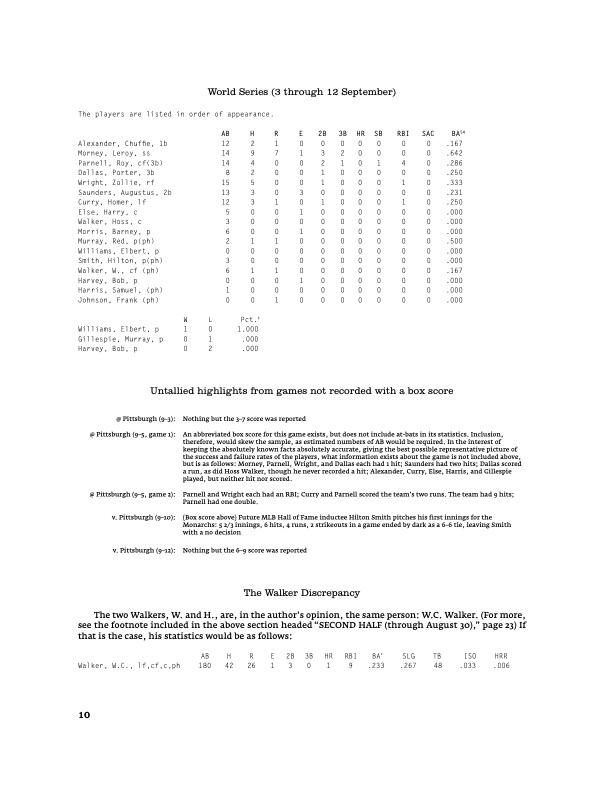

The Monarchs opened their World Series in front of a capacity crowd on September 3. “Returns of the games at Pittsburgh will be given at Tenth and Desiard Streets every day starting about 2 o’clock,” announced the Morning World. “This is the first time a Negro southern team has won the right to take part in the Negro World Series and the entire south is pulling for the Monarchs to win the series.” The first game in front of that crowd was unsuccessful for the Monarchs, while the second was a win.

The Monarchs broke a 1–1 tie in the 10th inning for what would be their only World Series victory. The following day was Labor Day, and the Pittsburgh fans celebrated “Louisiana Day” in honor of the visiting Monarchs as the team from Monroe lost a doubleheader. “The hustling, whole-hearted assault of the Monarchs, even though behind, made a hit with Greenlee field fans,” reported the Courier. “Rounds of applause greeted their determined efforts to stage a batting rally at two or three different points.” One of the Labor Day doubleheader losses served as an exhibition game, “with gate receipts going to charity,” so the Monarchs returned home down two games to one.14

For the first home game, Stovall made arrangements with area railroads, both the Missouri Pacific and Illinois Central, “for the purpose of bringing spectators from Little Rock, New Orleans, Alexandria, Shreveport and intervening points.” Though Chicago defeated Nashville four games to three to take the “Dixie World Series,” the Monarchs held a Negro Southern League pennant-raising ceremony prior to the opening inning of the first home game against Pittsburgh. The game that followed served as something of an anticlimax as the teams played to a 6–6 tie before darkness halted the contest. The following day, a September 11 Crawfords win made them one short of series victory. On September 12, the Monarchs lost once and for all.15

The Crawfords’ 1932 squad was managed by Oscar Charleston, who also played first base. Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, Satchel Paige, and Ted Radcliffe were also on the team. Those players are now in the pantheon of Negro Leagues immortals. The Crawfords, too, continued to be a successful franchise even after its stars moved to other teams. Monroe, however, quickly faded away. The team resumed play in a reformulated “minor” Dixie League the following season and dissolved by 1936. But many of its players—who contributed to such a successful season and brought a small Southern town, “the lynch law center of Louisiana,” to the precipice of a national championship (however makeshift it may have been)—went on to successful careers in larger markets.

Indeed, their talent was prolific. Homer “Blue Goose” Curry (a late-season addition from Memphis) played left field and pitched for the team, later enjoying a long and distinguished career with the Baltimore Elite Giants, Philadelphia Stars, and (again) Memphis Red Sox. Catcher Harry Else went on to play in the mid-1930s with the Kansas City Monarchs, making the East-West All-Star game in 1936. Monroe’s shortstop, Leroy Morney, had a well-traveled but substantial all-star career for a variety of Negro National League teams through 1944. Pitchers Barney Morris and Samuel Thompson enjoyed success after leaving Monroe, Morris with the New York Cubans and Thompson with the Philadelphia Stars and Chicago American Giants.

Right fielder Zollie Wright was another former Monarch to become an East-West All-Star, playing for Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia. Roy Parnell played center field and pitched for the Monarchs. He played on a variety of minor Southern teams before coming to Monroe. His most productive years came with the Philadelphia Stars in the 1940s, and his success earned him candidacy for a special 2006 Negro and Pre-Negro Leagues election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Though Parnell was ultimately not included in the final group of enshrined players, his candidacy validates his talent.

But the player who would become the most famous on the team did not join it until late August, when he came to Monroe from the Austin Black Senators. Hilton Smith’s impressive showing against the Monarchs convinced the team to purchase his rights for the remainder of the season, and he would stay in Monroe for two more years. Smith would become a powerful pitcher for the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1930s and 1940s, though his career was often overshadowed by fellow Kansas City pitcher (and former 1932 World Series foe) Satchel Paige. He is now a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.16

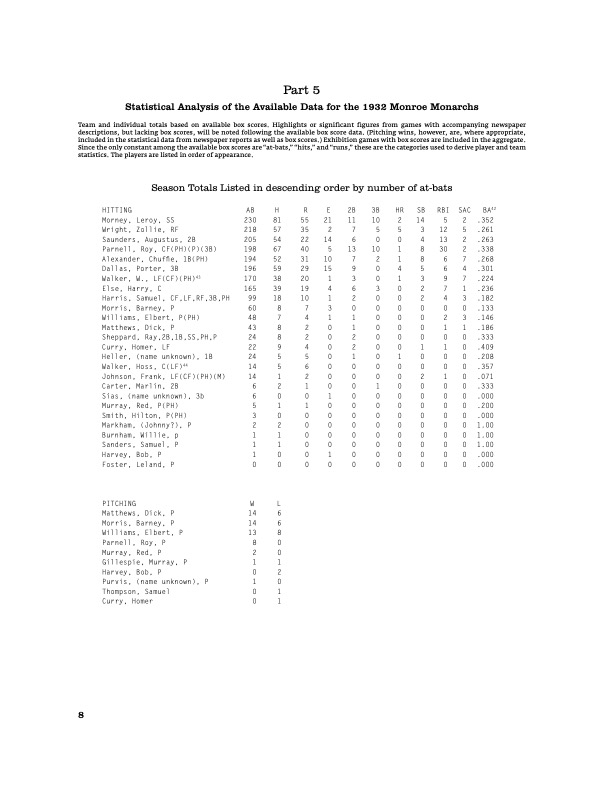

The statistics of these players and the rest of the 1932 Monarchs that follow are necessarily incomplete. The statistical inconsistencies of the Negro Leagues were only exacerbated in the Monarchs’ situation by (1) a newly created league struggling to stay afloat in the face of the Depression and (2) the realities of a small-town Southern team two years from its inception and four from its eventual demise. Monroe had a viable black press in 1932, though its Southern Broadcast did not begin until the middle of the year. Sherman Briscoe founded the Broadcast, which remained a solvent publication until 1939. Though Briscoe went on to serve as a press officer for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Executive Director of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, his paper’s longevity did not match his own. Only scattered editions of the Southern Broadcast from 1936 and 1937 now exist.17

Many of the surviving box scores of the Monarchs’ 1932 season come from the town’s white newspapers, the Monroe Morning World and the Monroe News Star, which, when compared with far larger mainstream newspapers in far larger markets, gave a significant amount of coverage to the local black team. Though many African-American papers throughout the nation published reports of the Monarchs’ games, fewer carried box scores. The Louisiana Weekly, Memphis World, Atlanta Daily World, Chicago Defender, and Pittsburgh Courier were among those who did.

What follows is an attempt to take some of the raw data from those papers and from other sources to create a statistical archive of the 1932 season—a measured documentation of a team whose prior appearances in scholarly work has been scarce and woefully unmeasured.

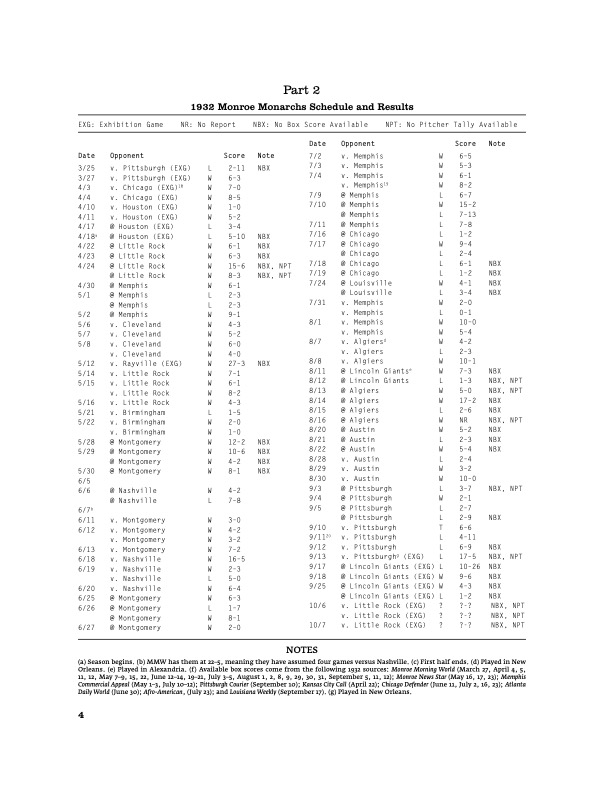

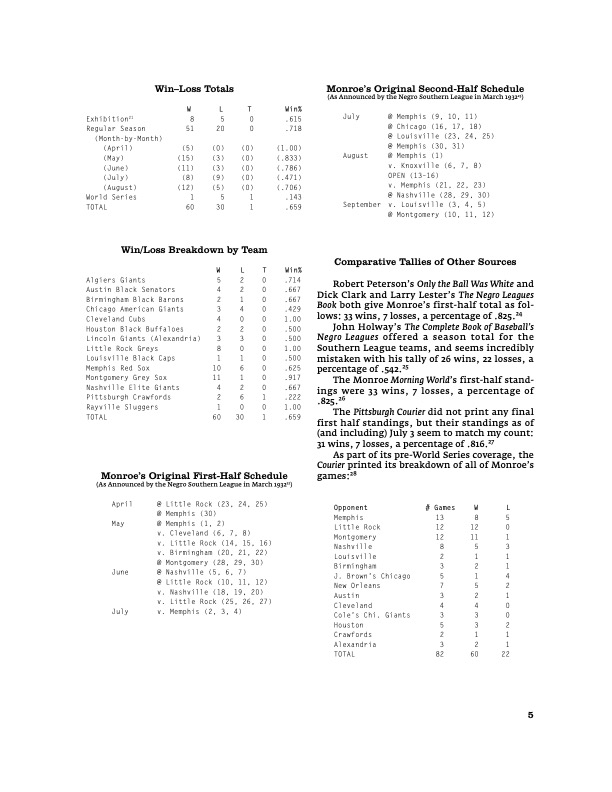

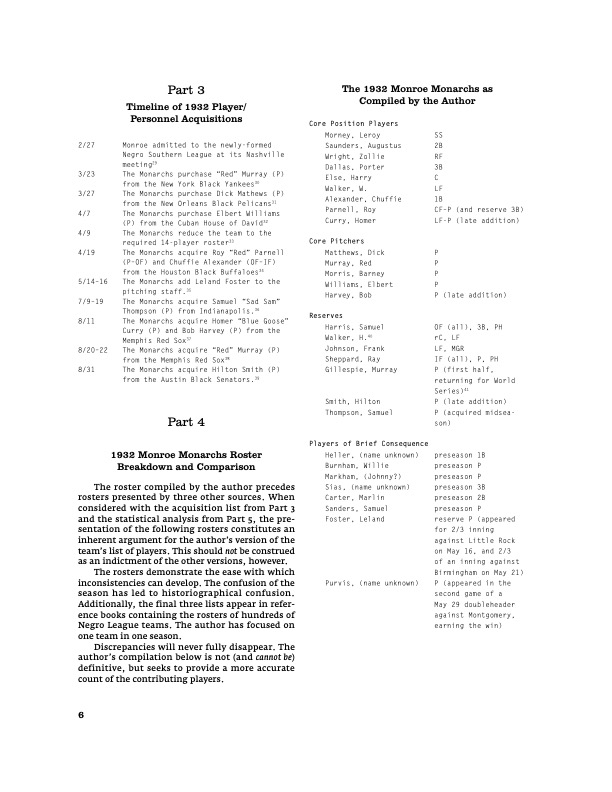

Part 2 of this study provides the Monarchs’ schedule and results, along with win and loss totals divided by month and by team played. It compares Monroe’s played schedule with the print- ed schedule as announced by the Negro Southern League. Finally, the section compares the author’s results to other statistical tallies from encyclopedic accounts that are incomplete and incorrect. Part 3 provides a timeline of player and personnel acquisitions prior to and during the season.

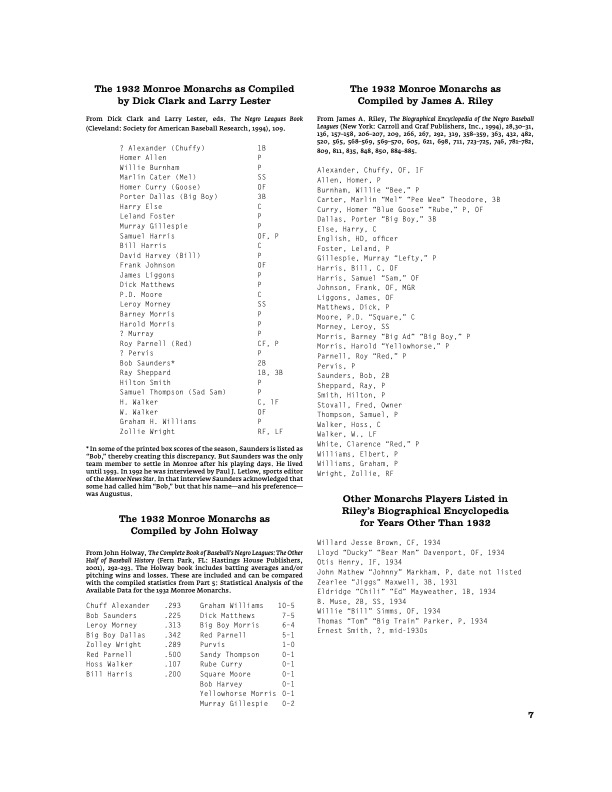

Part 4 catalogues the Monarchs’ 1932 roster and compares the complete roster to the accounts of other encyclopedic treatments that are incomplete and incorrect. The fifth and final part provides a statistical analysis of the available data for the Monarchs’ 1932 season. It includes an evaluation of the statistics of Monarchs’ opponents and leaders from other leagues to gauge the comparative success of the team.

Throughout most of the 1930s, the Monroe Monarchs remained on the periphery of Negro Leagues baseball. But the 1932 team proved a success. A questionable midseason decision by the president of the Negro Southern League kept the Monarchs from a pennant, but their participation in what most of the nation considered the black baseball championship for 1932 gave the team its proverbial 15 minutes of fame. What follows is an attempt to document those 15 minutes of fame, to return them to black baseball’s historical memory.

Click on images to enlarge:

THOMAS AIELLO is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Arkansas.

Notes

-

Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, vol. III, part I, Alabama–Missouri (US Government Printing Office, Washington: 1932), 979.

-

Fifteenth Census, vol. III, 965, 982, 990, 999, 1003.

-

New Orleans Item, May 6, 1919; New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 12, 1919; “The Monroe Lynching,” Southwestern Christian Advocate, June 12, 1919, 1–2; National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1918 (New York: Arno Press, 1969), 71–73, 104–105; and Papers of the NAACP, Part 7: The Anti-Lynching Campaign, 1912–1955, Series A, reel 12 of 30 (Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1982), 348–352, 354, 356, 373–380, 383, 393.

-

Michael E. Lomax, Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1860–1901: Operating by Any Means Necessary (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2003), xv–-xvi, xvii.

-

Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 122; DeMorris Smith, interview, September 2, 2004; “The Realty Investment Co. Ltd. to J.M. Supply Co. Inc.—Mortgage Deed, Sale of Land,” Record 79482, April 23, 1927, Conveyance Record, Ouachita Parish, Book 157, pp. 775–778, Ouachita Parish Clerk of Court; “J.M. Supply Co., Inc. to the Realty Investment Co., Ltd.—Mortgage Deed, Vendor’s Lien,” Record 79482, April 23, 1927, Mortgage Record, Ouachita Parish, Book 129, pp. 707–710, Ouachita Parish Clerk of Court; “J.M. Supply Co., Inc. to Fred Stovall—Cash Deed, Sale of Land,” Record 139386, May 21, 1930, Conveyance Record, Ouachita Parish, Book 20, pp. 435–456, Ouachita Parish Clerk of Court; Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of All 271 Major League and Negro League Ballparks Past and Present (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1992), 81; and Who’s Who in the Twin Cities (West Monroe: H.H. Brinsmade, 1931), 167.

-

Atlanta Daily World, 20, March 22, 1932; Pittsburgh Courier, March 19, 1932; and Birmingham Reporter, 12, March 26, 1932, April 2, 1932.

-

Chicago Defender, 4, 11, June 25, 1932.

-

Louisiana Weekly, July 9, 1932.

-

This is the formula generally repeated in historical accounts. Peterson’s Only the Ball Was White sets the standings as follows: Cole’s American Giants, 34–7, .829 winning percentage; Monroe Monarchs, 33–7, .825 winning percentage. The account of Dick Clark and Larry Lester is the same for the two front-running teams. John Holway’s The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues offered a season total for the Southern League teams, and wrongly noted “Nashville was awarded the first half, Chicago the second.”: Chicago American Giants, 52–31, .627 winning percentage; Monroe Monarchs, 26–22, .542 winning percentage. Chicago Defender, July 23, 1932; Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White; Dick Clark and Larry Lester, eds., The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994), 164; and John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, FL: Hastings House, 2001), 288, 292–293. See Part 2 for further details.

-

According to the Morning World, the first-half standings looked like this: Monroe, 33–7, .825 winning percentage; Chicago, 28–9, .756 winning percentage. The Pittsburgh Courier’s first-half standings as of July 3 tallied eight losses for Chicago: Monroe, 31–7, .816 winning percentage; Chicago, 31–8, .795 winning percentage. In contrast to Holway’s 26 wins and 22 losses for the season, the Courier tallied Monroe’s total as 60 wins and 22 losses. Monroe Morning World, July 6, 1932; and Pittsburgh Courier, July 9, 1932, September 3, 1932.

-

Monroe Morning World, July 28, 1932; Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1932; and Chicago Defender, July 9, 1932, August 13, 1932.

-

For more on coverage of the series by the African-American press in 1932, see Thomas Aiello, “Black Newspapers’ Presentation of Black Baseball, 1932: A Case of Cultural Forgetting,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 15 (Fall 2006).

-

Jim Bankes, The Pittsburgh Crawfords: The Lives and Times of Black Baseball’s Most Exciting Team (Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown Publishers, 1991), 23, 26–27; Chicago Defender, July 2, 1932; and Pittsburgh Courier, April 9, 1932, August 27, 1932.

-

Much of this brief treatment of the 1932 World Series comes from Thomas Aiello, “The Casino and Its Kings Are Gone: The Transient Relationship of Monroe, Louisiana with Major League Black Baseball, 1932,” North Louisiana History 37 (Winter 2006): 15–38. Though one of the Pittsburgh games was scheduled to be played in Cleveland, all took place at Greenlee Park. Pittsburgh Courier, September 10, 1932; Chicago Defender, August 27, 1932; Monroe Morning World, August 31, 1932, September 10, 1932.

-

Monroe Morning World, September 13, 1932.

-

Two years later, another Hall of Fame player would come from Shreveport to start his career with the Monroe Monarchs. Willard Brown played shortstop for the team before being purchased by J.L. Wilkinson to play for the Kansas City Monarchs. The same special 2006 Hall of Fame election that failed to elect Roy Parnell did elect Brown for induction. Much of this brief account comes from Riley’s Biographical Encyclopedia, 206–207, 209, 266–267, 568, 569–570, 605, 723–725, 781–782, 884–885. Additional information from “Hilton Smith Autobiographical Account,” Player File: Smith, Hilton, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY; Tri-State Defender, April 13, 1974; “Pre-Negro Leagues Candidate Profile: Roy A. ‘Red’ Parnell,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, www.baseballhalloffame.org/hofers_and_honorees/parnell_red.htm, accessed February 21, 2006; “Pre-Negro Leagues Candidate Profile: Willard Jessie ‘Home Run’ Brown,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, www. baseballhalloffame.org/hofers_and_honorees/brown_willard. htm, accessed February 21, 2006; and Steve Rock, “Former Monarchs Pitcher Hilton Smith Elected to Baseball Hall of Fame,” Kansas City Star, March 7, 2001.

-

Jessie Parkhurst Guzman, ed., 1952 Negro Year Book: A Review of Events Affecting Negro Life (New York: William H. Wise & Co., 1952), v; Who’s Who Among Black Americans, 1977–1978, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Northbrook, IL: Who’s Who Among Black Americans Publishing Company, 1978), 98; and Southern Broadcast, July 11, 1936, February 6, 1937.

-

The exhibitions were against the Rube Foster Memorial Giants—often confused, even in contemporary press reports— as the Chicago American Giants. A series of articles in the Kansas City Call in early April report on both teams and make their differences clear. Kansas City Call, 1, April 8, 1932.

-

The game total by this count is 42, with 35 wins and six losses (minus the exhibitions). This differs from any other account, contemporary or historical, of the season’s first half. I stand by this count. The selective presentation by newspapers and the overall confused state of Negro League Baseball in 1932 both argue for the necessity of a new count. The contemporary and historical controversy over the first half standings, if nothing else, discredits any consistency in former counts. See below for a catalog of other tallies and for the Monarchs’ original schedule as announced by the Negro Southern League in March 1932.

-

Available box scores come from the following sources: Monroe Morning World, March 27, 1932, April 4, 5, 11, 12, 1932, May 7, 8, 9, 15, 22, 1932, June 12, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21, 1932, July 3, 4, 5, 1932, August 1, 2, 8, 9, 29, 30, 31, 1932, September 5, 11, 12, 1932; Monroe News Star, May 16, 17, 23, 1932; Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 1, 2, 3, 1932, July 10, 11, 12, 1932; Pittsburgh Courier, September 10, 1932; Kansas City Call, April 22, 1932; Chicago Defender, June 11, 1932, July 2, 16, 23, 1932; Atlanta Daily World, June 30, 1932, Afro-American, July 23, 1932; and Louisiana Weekly, September 17, 1932.

-

The four final games with the Lincoln Giants of Alexandria, Louisiana are considered exhibition games, as they take place after the close of the World Series.

-

Pittsburgh Courier, 19 March 1932; and Atlanta Daily World, March 22, 1932.

-

Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1932; and Chicago Defender, July 9, 1932.

-

Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 269; and Dick Clark and Larry Lester, eds., The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994), 164.

-

John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, FL: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 288, 292–293.

-

Monroe Morning World, July 6, 1932.

-

Pittsburgh Courier, July 9, 1932, September 3, 1932.

-

Pittsburgh Courier, September 3, 1932.

-

Louisiana Weekly, March 5, 1932; and Shreveport Sun, March 19, 1932.

-

Murray never played for the Monarchs in the first half of the season. He somehow made his way to Memphis, before returning to the Monarchs in late August. See below. Monroe News Star, March 24, 1932.

-

Chicago Defender, April 2, 1932.

-

Monroe Morning World, April 8, 1932.

-

Monroe Morning World, April 9, 1932.

-

Monroe Morning World, April 21, 1932.

-

Louisiana Weekly, May 21, 1932.

-

Thompson was the losing pitcher on Tuesday, 19 July loss to Chicago, described by the Chicago Defender as the “former Indianapolis twirler.” Chicago Defender, July 23, 1932.

-

Announced in the Monroe Morning World, August 26, 1932. But the players appeared in games versus the Lincoln Giants beginning on August 11.

-

His first appearance came at Austin, August 22, 1932. Monroe Morning World, August 23, 26, 1932.

-

Monroe Morning World, September 10, 1932.

-

See “The Walker Discrepancy” in Part 5.

-

Gillespie was suspended by the Southern League for the second half of the season. See Pittsburgh Courier, September 7, 1932 for his return.

-

Batting average is the only statistic in this section not physically provided by the actual box scores. Further derivative statistics follow under the heading “Derivative Statistics.”

-

On June 12, the Monarchs played a doubleheader with the Montgomery Grey Sox, and the box score for the first game lists the left fielder as Maher—a name never mentioned before or after. The number of incorrect spellings and misinterpretations of names leads the observer to conclude that the handwritten box score submission that included Walker appeared to be Maher to the Monroe Morning World’s typesetter. Walker (Maher) was 1 for 4 with 0 runs.

-

There here exists a discrepancy that must be acknowledged. James Riley’s The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues lists two Walkers as players for the 1932 Monarchs. Neither are very well known. W. Walker is listed as a left fielder. H. Walker is listed as a catcher. In a game against the Chicago American Giants, the box score of which appears in the Chicago Defender, 23 July 1932, Walker is listed as playing lf and c in the Saturday box score. The dearth of information available about these players (even accurate first names) leaves open the very real possibility that this is these two players are the same, particularly with the prevalence of box score typographical errors. Box scores generally list “Walker” and a position, so absolute accuracy is impossible. For the sake of the best possible sample, however, I have separated the catching Walker from the left fielding Walker. One newspaper account, however, describes W. Walker as W.C. Walker, “former Campbell College star.” This information doesn’t discount the possibility that H. and W. Walker were different players, but it seems to suggest that there was one known Walker on the team, making the possibility that W.C. Walker was the only member of the 1932 Monarchs more than plausible. Atlanta Daily World, 15 September 1932; and James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 809, 811. Following the combined season totals below, the statistics of both possible Walkers are combined to demonstrate the totals of one player, W.C., (in the event that the Walkers were indeed one player) under the heading “The Walker Discrepancy,” page 10.

-

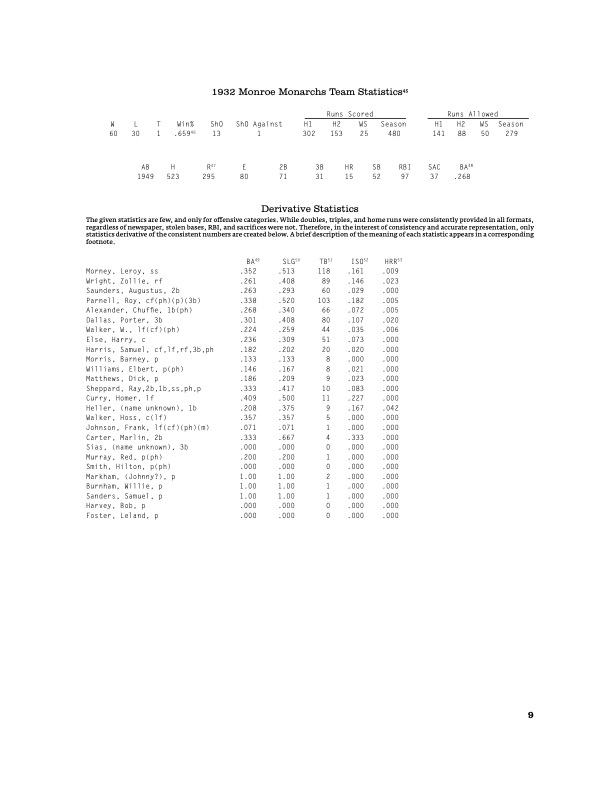

All totals derived from the available data. Wins, losses, and scores are totals from Part 2: 1932 Monroe Monarchs Schedule and Results. Statistical performance numbers are totals from the “Season Totals” section of Part 5: Statistical Analysis of the Available Data for the 1932 Monroe Monarchs, page 8. As in the First and Second Half statistical breakdowns, exhibition games with available scores (with the exception of those taking place after the close of the World Series) are included in the total runs scored and allowed.

-

Winning percentage is the only pitching statistic not physically provided by the actual box scores. The lack of consistent details about specific pitching performance categories makes derivative pitching statistics virtually impossible to provide. The percentage is calculated by dividing the number of wins by the number of decisions.

-

The run totals for this section of the team statistics are derived from available box scores, and thus from fewer games than are the run totals based solely on the reported wins and losses. Addition of runs not included in the box scores cannot be included in this section, as they would skew the representative sample the box score statistical analysis is supposed to provide.

-

Batting average is the only statistic in this section not physically provided by the actual box scores. Further derivative statistics follow under the heading “Derivative Statistics.”

-

Batting average is simply the batter’s number of hits divided by his number of at bats (AB above).

-

Slugging percentage follows this formula: [singles + (2 x doubles) + (3 x triples) + (4 x home runs)] / at bats.

-

The total bases statistic follows this formula: singles + (2 x doubles) + (3 x triples) + (4 x home runs).

-

The isolated power statistic follows this formula: total bases – hits / at bats. The original formula calculated the “total bases” by awarding a 0 for singles, 1 for doubles, 2 for triples, and 3 for home runs. Here, total bases is calculated as described in note 3 above.

-

Home run ratio is calculated by dividing the number of a batter’s home runs by his number of at bats.

-

Batting average is the only statistic in this section not physically provided by the actual box scores. Further derivative statistics follow under the heading “Derivative Statistics,” pages 26-27.

-

Note, as mentioned above, that hits, runs, errors, and at bats are the most consistently noted statistics. In this section, for example, though Chicago has scored 15 runs, they have no listed rbi’s. The box scores for games with Chicago did not include rbi as a statistic, and so is not there. While the first four numbers are clearly the most complete, the numbers to the left of the rbi column are reasonably accurate. The same derivatives generated above are generated below the hard numbers section. The given numbers are for the games noted in Part 2, “1932 Monroe Monarchs Schedule and Results,” as having an available box score. The total number of games used to derive each team’s statistics against the Monarchs follows the team name in parentheses.

-

The Pittsburgh statistics presented here include the three World Series games with available box scores and the early exhibition game. Pittsburgh’s individual and team World Series statistics are included below.

-

The statistics here correspond to the three box scores used to compile the Monarchs World Series statistics. See above.

-

This Jud Wilson, one in a litany of future Hall of Fame inductees from the 1932 Crawfords, is the same Jud Wilson who led the 1932 East-West League in batting average for 1932. Wilson moved to the Crawfords after the East-West collapse. See below.

-

The East-West League, the other major Negro Baseball League in 1932, folded early in June. The final statistical release by the league was published in the Baltimore Afro American, 11 June 1932. The statistics and derivative numbers for individual and team East-West sections come from that source.

-

Minimum of fifty at bats, for batting average and the rest of the East-West League statistical leaders.

-

Smith was 4 and 0 in six games, with thirty innings pitched.

-

The Cuban Stars’ home run ratio just edges Baltimore’s .017.

-

This statistic comes from the Baltimore Afro American, 25 June 1932. Soon after this standings release, the league folded.

-

The Cotton States League was a white minor league of teams from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi. It included, among other teams, the Monroe Twins, who played across town from the Monarchs in Desiard Park. The league, however, did not outlast the NSL. It folded early in July. The final statistical release by the league was published in the Monroe Morning World, 10 July 1932. The statistics and derivative numbers for individual and team Cotton States sections come from that source, as do the Monroe Twins statistics that follow.

-

Minimum of fifty innings pitched imposed by the author.

-

The Pine Bluff rookie came from Dallas, and though the local paper used first names in its reports on the Pine Bluff Judges, Danforth was always called C.B., often with the nickname “Tarzan” added. Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, 22, 24, 26 April 1932, 1, 15, 27 May 1932.