The Delaware River Shipbuilding League, 1918

This article was written by Jim Leeke

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

Baseball leagues flourished in American shipyards during World War I as legions of workers built warships and troop transports to safeguard the Atlantic sea lanes and carry men and materiel to Europe. Among the best of these circuits was the Delaware River Shipbuilding League of 1918. Centered in Philadelphia, it represented eight shipyards operating along the river in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania:

- Chester Ship – Chester, Pennsylvania

- Harlan & Hollingsworth – Wilmington, Delaware

- Hog Island – Philadelphia

- Merchant Ship – Bristol, Pennsylvania

- New York Ship – Camden, New Jersey

- Pusey & Jones – Wilmington (replaced League Island Navy Yard after two games)

- Sun Ship – Chester, Pennsylvania

- Traylor Ship – Cornwells, Pennsylvania

“The Delaware River Shipbuilding League is due for a successful season in its first year on the baseball diamond judging by the results of Saturday’s games,” the Philadelphia Public Ledger commented after opening day.1

The newspaper also pointed out what it considered “a defect in one of the rules of the organization which is entirely too stringent.” A worker had to be on the job for 40 days before he was eligible to suit up for his shipyard team. The Public Ledger thought 10 days would have been wiser.

“For the opening any player should have been eligible up until Saturday,” it declared, “and in order to avoid disputes all men who were in uniform on Saturday should be declared eligible, especially so because of the shortness of the season.”2 The stricter requirement remained in place, and would bedevil the league the rest of the season.

Only two of the four opening games drew sizeable crowds. The Traylor-Hog Island turnout was especially disappointing. Traylor had a “class infield, but… should hunt up an entire new outfield,” the Public Ledger opined. A shipyard official brushed aside any such worries. “We are in this for the sport alone,” he said, “and if some other fellow gets Ty Cobb and (Grover Cleveland) Alexander, let him trot them out and, win or lose, we will be shouting just the same.”3

The Traylor man was perhaps clairvoyant. On May 13, the same day that his comments appeared, a Selective Service board in South Carolina notified Joe Jackson, of the champion Chicago White Sox, that it had reclassified his draft status. “Shoeless Joe” was suddenly set to join the next group to be called for military service, a situation that Jackson initially seemed to accept.

“Well, the old boy will be out there slugging the Dutchman pretty soon,” Jackson said in Philadelphia, where the White Sox had just played the Athletics. “And if I ever draw a bead on one of them birds, it’ll be all off with him.”4

The next morning, however, at the urging of his wife, Jackson instead reported for work as a painter at the Harlan yard in Wilmington, a subsidiary of mighty Bethlehem Steel. Shipyard workers, like those in other vital war industries, were usually exempt from military service. Although the outfielder was illiterate, the shipyard not only accepted Jackson, it immediately promoted him to painting inspector.

“If Jackson should stay at the shipyard as an employe [sic] he would be eligible to play in the Bethlehem Steel Baseball League as a member of the Wilmington team,” a wire service reported. “This organization has teams at Bethlehem, Lebanon and Steelton, Pa., Fall River, Mass., Wilmington, Del., and Sparrows Point, Md.”5

The Delaware River and Steel leagues both played their games on Saturdays, and Harlan had a team in each. Jackson suited up for Harlan’s Steel League nine, and appeared in his first game on June 1. Fans of the company’s Delaware River team would have to wait until the end of the season to see him.

Any big-league player who sought a shipyard job in 1918 heard abuse from many fans and sportswriters. A former St. Louis player serving in the Navy saw the phenomenon first hand in a shipyard game featuring several ex-Giants. “Nothing was too mean to call them,” he wrote, “and if they got a dollar for every time some one called them ‘slackers’ or ‘trench-dodgers’ they must have gotten round-shouldered carrying their money home.”6

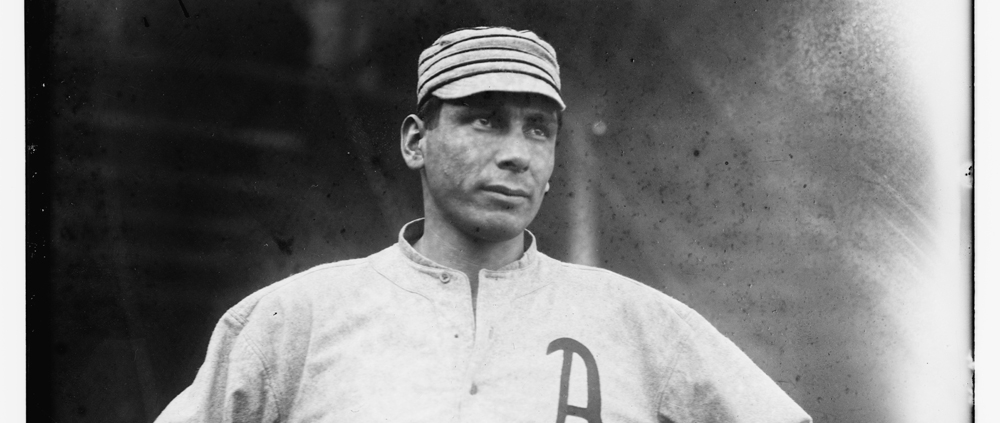

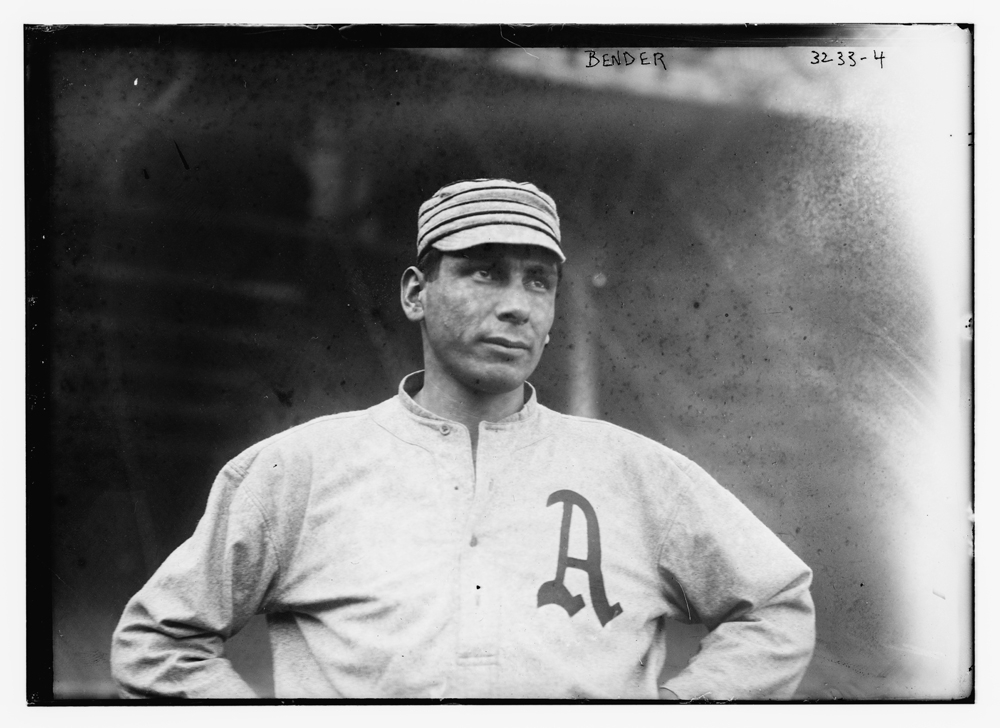

Charles “Chief” Bender’s major league career was essentially over when he pitched for the Hog Island team. The Hog Island yard employed 35,000 workers at the time. (Library of Congress)

Jackson, especially, became a lightning rod for condemnation, but many people defended him. Former Chicago teammate Alfred “Fritz” von Kolnitz, a major in the wartime Army, insisted that Shoeless Joe had every right to hold a shipyard job. “During the draft period, I will venture, there were thousands of men walking the streets in civilian clothes with exemption papers in their pockets with far less claims than Joe,” he later wrote to a sportswriter.7

The Delaware River League had about two dozen recent or retired big leaguers on its rosters, most of them journeyman players. Among the better-known players was former Athletics star Charles “Chief” Bender, whose time in the majors was over (although he would pitch one final inning for the White Sox in 1925). With Joe Jackson watching from the stands as a spectator, Bender made his league debut the second weekend of play, appearing on the road in relief for Hog Island. The enormous Hog Island yard employed 35,000 workers on the site of what is now the Philadelphia airport.

“‘Chief’ Bender has at last broken into the box score of the Delaware River Shipbuilders’ League,” the Public Ledger reported. “He accepted the mound for the final three innings of the Harlan-Hog Island encounter at Wilmington, which the former captured by 6–4.”8 Although later claimed on waivers by the Yankees, Bender didn’t report to New York and would remain in the shipbuilding league until hurt in a car crash in August.

Despite having Bender and other experienced players, the Delaware River Shipbuilding League was still an industrial circuit. The hot club early in the season was Chester Ship, which played in nearby Upland on a field called White Hip. Chester fielded perhaps the river league’s most colorful and diverse team, with one player who had once been under contract to the Browns, another to the Athletics, a pair of ex-minor leaguers from the New York State and North Carolina leagues, and a former player from Colby College. Its roster also included three Chinese ballplayers from Hawaii, who “put up a brand of base ball that Chester fans like to see.”9

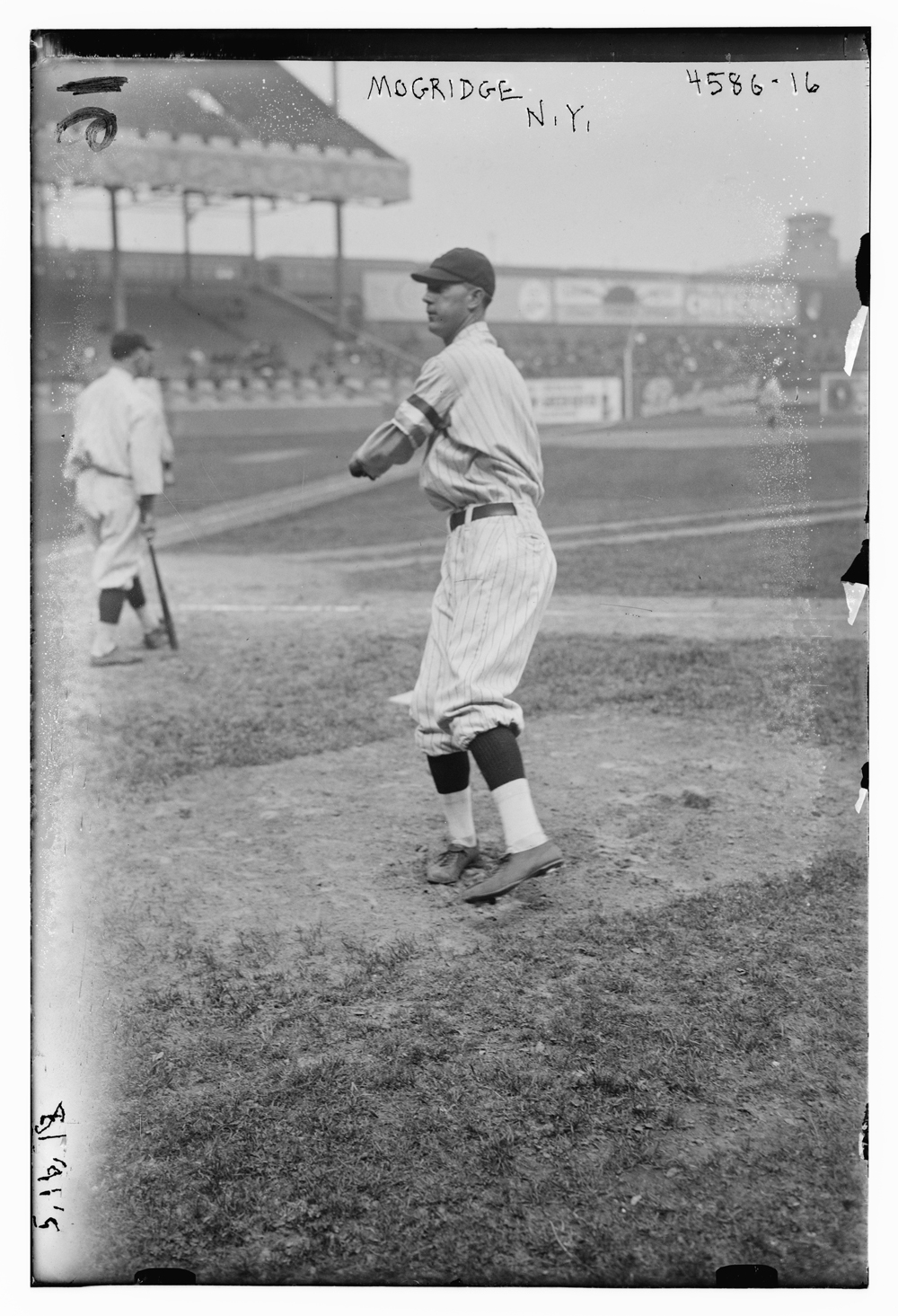

Widespread national criticism of shipbuilding leagues grew as the season progressed. New York Yankees manager Miller Huggins let loose a tirade in mid-May, after pitcher George Mogridge jumped the team for a shipyard job.

“A half dozen players on my club have been approached by men who presumably are conducting the welfare work for the Bethlehem Steel Company,” Huggins charged, “and I have authoritative knowledge that players on virtually all the big league clubs who thus far have played on the Atlantic seaboard, have received offers similar to those made to my men.” The outraged manager added that one Yankee “was offered more money for going to one of the Atlantic Coast shipbuilding yards to play baseball and learn a skilled trade than his American League baseball contract called for.”10

The government looked into this and similar allegations, including one made by a US senator. Officials yanked at least two ballplayers from the so-called “paint and putty” leagues and sent them to an Army training camp on Long Island. Otherwise, little appeared amiss in the shipyard leagues. A vice president of the US Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation, Howard Coonley, later announced that the number of ballplayers “camouflaging” as shipyard workers was actually negligible.

“The stories that all ball player workmen at $500 a month have to do is punch a clock in the morning is false, says Coonley,” The Sporting News reported. “He says ‘with very few exceptions’ everyone [sic] of them does a full day’s work. Furthermore, he praises the efforts that have been made to make baseball the main recreation for the ship yard workers and says an even more expansive sport program is being planned, to include soccer, football, trap shooting, and other activities.”11

Significantly, directors of the New York shipyards voted to limit teams in their league to two ex-major leaguers apiece. “In the Philadelphia district there seems no limitation to the number of former major leaguers on a ball team, as there apparently are enough to go around,” The Sporting News tartly added.12

By the middle of June, as controversy still bubbled, Chester Ship led the Delaware River league with a 6–0 record. New York Ship was a game back with one loss. Although eligible to play, Shoeless Joe hadn’t yet taken the field for Harlan’s river club. “Manager [Fred] Gallagher, of Harlan-Bethlehem, of the Ship League, will find it necessary to requisition the services of Joe Jackson if the Wilmington aggregation is to stay in the running at all,” the Public Ledger commented. “They dropped to fourth place by losing to Hog Island, 4–3. It was the first game for Hog Island on its new grounds at Brill Park.”13

The following Saturday featured an important Chester-Harlan matchup. The Public Ledger expected “the largest crowd that ever witnessed a game in Wilmington,” and added that it was “almost a certainty that Joe Jackson and other big leaguers will appear.”

“I don’t care who they play. We are going to win,” Chester Manager Frank Miller confidently promised. Fred Gallagher, skipper of the Harlan nine, said that his club “must win (this) game or quit the league.”14

Chester took the highly anticipated contest, 3–0, in front of 5,000 fans, besting the former White Sox battery of Claude “Lefty” Williams and Byrd “Teddy” Lynn. Williams had won 17 games for Chicago in 1917 and six more early in 1918, and had unwisely speculated on what he would do to poor Chester, “but bragging doesn’t win games, and Williams soon found it out.”15 The league leaders plated all three runs in the third inning before chasing Williams in the sixth. Jackson, Williams’s former Chicago teammate, didn’t appear—and regardless of Gallagher’s bold statement, Harlan stayed in the league.

Chester finally lost a game on July 6, bowing 7–5 to New York Ship at Camden. The Chester Times acknowledged the loss, but devoted more space to describing Chief Bender leading Hog Island to a 6–3 win over Merchant Ship the same day. “Bender Does the Trick,” the headline read. “Chief Bender, doing the twirling for the Islanders, showed all of his old-time cunning, and had the Bristol boys at his mercy all during the game.”16

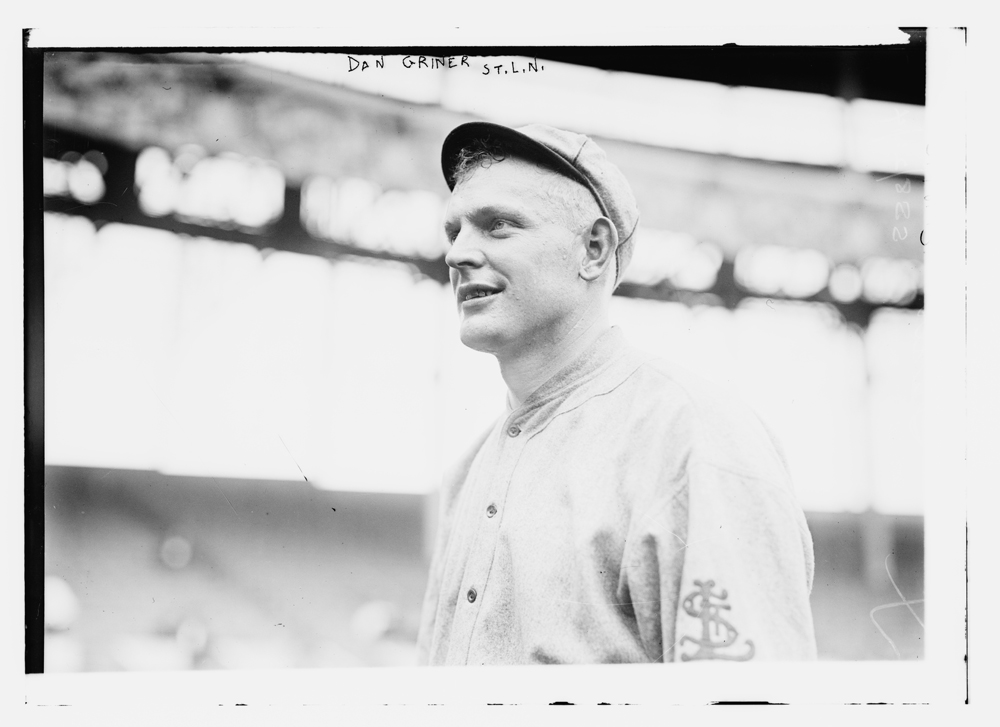

Dan Griner had been a pitcher for the Cardinals and the Dodgers, but gave up two home runs to Shoeless Joe Jackson in the final game of the 1918 shipbuilding league playoffs. (Library of Congress)

Hog Island now trailed Chester by only half a game. “When Hog Island started the season it looked like anything but a ball team that played the opening contest against Traylor at Franklin Field, but hard work has molded together one of the best clubs hereabouts,” the Public Ledger declared. “Great interest is centered in next Saturday’s game between Hog Island and Chester.”17

More than 2,000 fans watched the thriller the following week at Upland. Ebullient headlines in the Chester Times told the tale: “Chester Wins Thrilling Game From Hog Island/Shipmakers Stage Wonderful Rallies, Tieing [sic] the Score in the Eleventh and Chasing the Winning Run Over in the Next Period—Long, Miller’s Southern League [sic] Heaver, Pitches Great Ball.”18

Chester’s record now stood at 9–1. “Chester Ship virtually won the pennant of the Delaware River Ship League by defeating Hog Island, 4 to 3,” the Public Ledger opined.19

Despite the wonderful game, the real excitement that week had centered on Red Sox pitcher George Herman Ruth. On the fourth of July, headlines on sports pages across the country declared that Ruth had jumped the Boston club to pitch for Chester. Boston management threatened injunctions, but teammates didn’t believe the news and said they expected to see the Babe back any day. His Red Sox pals were right. Ruth had stormed home to Baltimore after an argument with Manager Ed Barrow, but returned once tempers cooled.

Chester Manager Frank Miller later conceded that he had received a wire from Ruth, but said the pitcher had asked only to play for his team on the holiday, and hadn’t inquired about a job in the shipyard.

“Ruth doesn’t even know I am managing the Chester team,” Miller insisted. “He probably thinks I am still running the Upland club, which was abandoned because of the war. The Chester Shipbuilding Company is not financing the ball club. It was simply organized by the employees and has to be self-supporting.”20

Draft calls and enlistments continued depleting big-league rosters as the summer wore on. A government “work or fight” order covering male workers nationwide added to the woes. Shipyard teams naturally attracted many worried ballplayers. Hog Island Manager Johnny Castle, who’d had a cup of coffee with the Phillies in 1910, stoutly defended his team’s ex-big leaguers.

“If any new men wish to enter this work they can start at about $35 a week and they will earn every cent they get,” Castle said. “If they show any unusual ability they will receive more. Not one cent extra will be paid to ball players. Hans Lobert and Chief Bender are on the job from morning until night and play ball on their off days. That’s how things are run at Hog Island. I don’t know anything about the other yards.”21

Shipyard workers and Philadelphia-area fans alike seemed to accept such arguments. The Delaware River league drew good crowds as the summer waned.

“Shipyard baseball is a very exciting branch of our great national outdoor sport,” wrote Robert W. Maxwell, the Public Ledger sports editor. “It is beginning to cut a wide swath in the sporting world, and if the big leagues take the count these independent teams will step in and furnish the fans some real fun and amusement. It is a different kind of baseball, but the spectators are handed more thrills.”

Maxwell described the rural Upland field, where 3,500 fans could watch Chester play Harlan, as “one of the most picturesque spots we have ever seen…On that field you can see more exciting baseball in one afternoon than you can witness in a modern park in a month.”22

George Mogridge defected in mid-May from the New York Yankees to the shipbuilding league, prompting a tirade from manager Miller Huggins against the aggressive recruiting. According to Huggins, one of his players “was offered more money… than his American League baseball contract called for.” (Library of Congress)

This was a hardscrabble shipyard league in wartime, however, and hardly a dreamy idyll. Several teams played their home games not in pastoral perfection, but within the confines of their own clanging shipyards. An exhibition game between Chester and Sun Ship at the latter’s new athletic field on a raw, rainy Memorial Day provided a perfect example.

“On all four sides of the field are tents pitched for the shelter of a company of soldiers who are training and on guard duty at the plant,” the Chester Times reported. “The sight was an attraction in itself and the boys went through their drills while the game was in progress. Another singular incident was the launching of a minesweeper by the Sun Company. The boat glided into the Delaware while the game was ending and no one knew anything of the launching.”23 (Later in the season, fans also saw the launching of a cargo ship during a game at the Harlan yard in Wilmington.)

Chester had the pennant nearly sewn up in late July. “Frank Miller and his crowd of Chester clouters have captured the championship of the Delaware River Ship League. They visited Bristol on Saturday and had a slugfest at the expense of Merchants,” the Public Ledger reported—somewhat prematurely, as it turned out.24

Questions about player eligibility still beset the league. A week after the Public Ledger item appeared, Chester, Merchant, and Sun all were forced to forfeit a game apiece, with two more games still under protest. “The managers accepted the rulings gracefully, claiming they did so in ignorance, believing the men protested had fulfilled all the league qualifications,” the Chester Times explained.25 The uncertainty persisted far into August. “DELAWARE RIVER SHIP TITLE STILL UP IN AIR ON PLAYERS’ ELIGIBILITY,” the Public Ledger headlined.

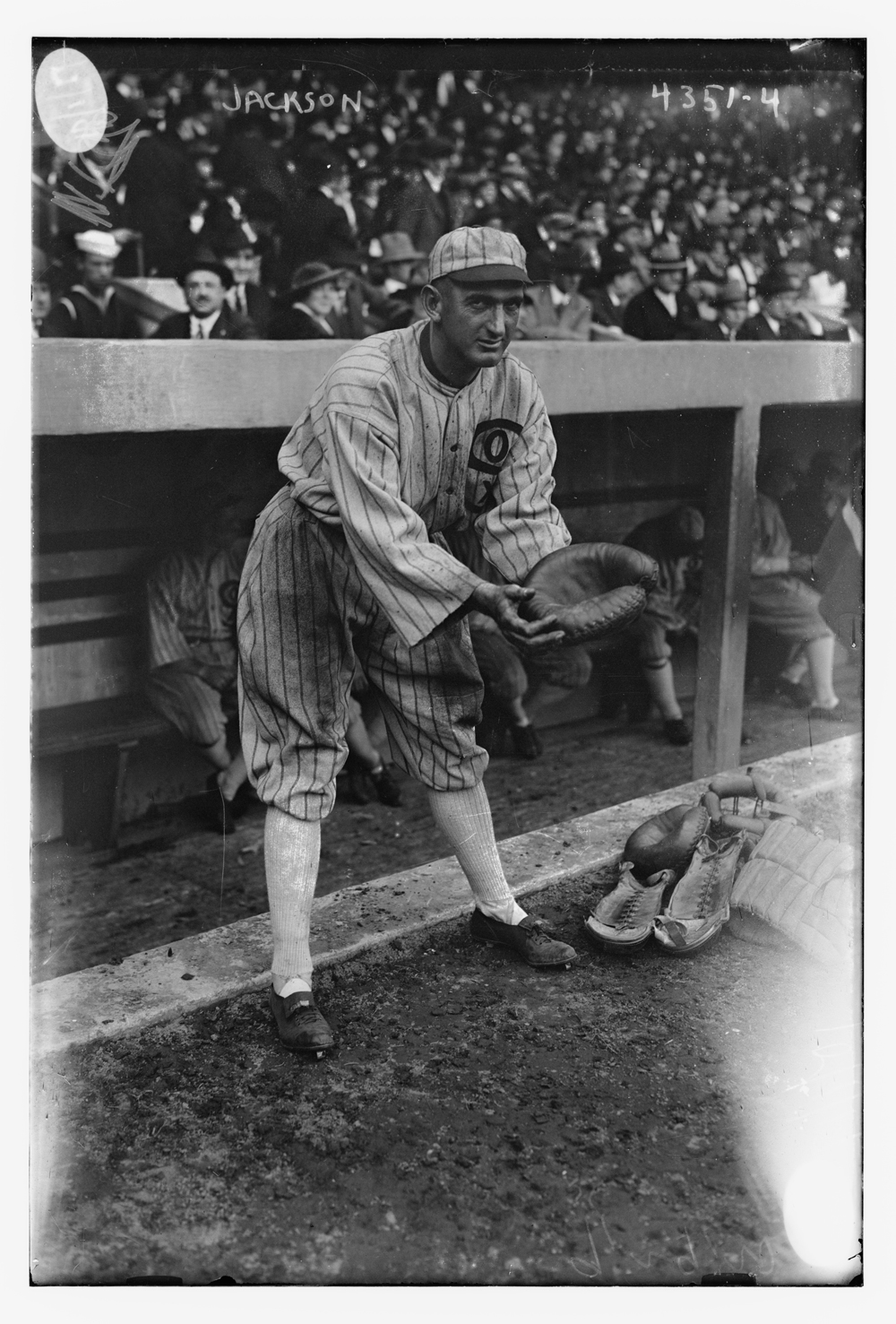

Joe Jackson went to work as a painter at a subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel and suited up for his first game Harlan’s Steel League on June 1. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

“The pennant in the Delaware River Shipyard Baseball League will not be awarded until the eligibility status of a number of players under question has been further investigated,” said Edgar S. McKaig, league secretary and a member of the Emergency Fleet Corporation.26 The season ended with Chester, Harlan, and Hog Island all even.

“TRIPLE TIE IN SHIPYARD LEAGUE WILL BE BROKEN BY END OF THE WEEK,” the Public Ledger announced.27

The tie wasn’t broken on the diamond, but rather in corporate meeting rooms. An eligibility committee issued a ruling on August 22, taking victories away from both Chester and Hog Island. As a result, the Chester club plummeted from atop the standings with a record of 12–2 to fourth place at 8–6. Harlan was suddenly tied with New York Ship, both with revised 11–3 records.

“CHESTER LOSES TO ‘OFFICIALS,’” blared the Chester Times. “There is no denying but Chester has the best team,” the paper groused. “It is unfortunate that a league of this kind should have fielded such an incompetent set of officials who might do well in deciding a game of ceckers, [sic] but are way off in baseball.”28

The league arranged a one-game Harlan-New York playoff, set for noon Wednesday, August 28. The Strawbridge & Clothier Athletic Field at 63rd and Walnut Streets in Philadelphia provided the neutral site.

Harlan’s other baseball team meanwhile had finished third in the Steel League following a 19-game schedule. Joe Jackson, who had led the Bethlehem league with a .393 batting average, now at last joined Harlan’s Delaware River lineup. Former Washington Nationals Patsy Gharrity and George Dumont also made the switch with him.

“Just what the eligibility rules of the Shipyard League are we do not know,” wrote Philadelphia Inquirer sportswriter Edgar Wolfe (under the pseudonym Jim Nasium), “but Chester must have committed murder if they were found guilty enough to have their games thrown out, while the acts of Harlan in reinforcing its team with players from another league solely for the decisive championship contest can be considered innocent.”29

Harlan easily won the playoff game, 5–0. Jackson played center field, went one for three at the plate, walked once, and scored a run. “With Joe Jackson the Wilmington Bunch Grabs Play-off,” the Chester Times headlined.30 Still resenting the technical ruling that had cost Chester the pennant, the newspaper said little else about Shoeless Joe’s very belated league debut.

The playoff victory next sent Harlan into a best-of-five series for the championship of Atlantic Coast shipyards. The new opponent was Standard Shipbuilding of Staten Island, which had won the New York Shipyard League pennant. Jackson again was in the Wilmington lineup for the opener September 7 at the Phillies’ ballpark, the Baker Bowl. Standard led the game 2–1 entering the ninth inning.

“The Harlans looked like a beaten team until Jackson, who is suffering with an injured right foot, took Dumont’s place at bat in the ninth,” the New York Sun reported.31 Shoeless Joe “lammed out a hard drive down the first base line for a single,” the Inquirer added. “Jackson could have easily made a two-bagger out of the hit if it had not been for his injured foot, as it was all he could do to reach first.”32 The single started a rally that brought Harlan a 3–2 victory.

The series shifted north to the Polo Grounds the following day. In a steady drizzle, and with Jackson out of the line-up, the old Chicago battery of Williams and Lynn held Standard scoreless before 4,000 fans. Two first-inning runs held up for Harlan’s 2–0 victory.

The Wilmington team went for the sweep back in Philadelphia on September 14. Jackson returned to the Harlan lineup before 4,500 fans, doubled, and homered twice off former Cardinal and Dodger pitcher Dan Griner. “Shoeless Joe was a whole show in himself,” the Public Ledger marveled.33

“When Jackson hit his second home run, which virtually clinched the game and series for Harlan, the Wilmington fans went money mad and showered him with greenbacks,” the New York Sun added. “For more than five minutes he was kept busy walking to the boxes and pulling in bills. After he had his fist full he walked over to a box directly behind home plate and handed them to his wife.”34

“Joe was not a bit backward about accepting the financial reward and he made a tour of the boxes collecting everything handed out,” reported the Phila-delphia Inquirer, which put the total windfall at $60.35

The 4–0, two-hit victory by Williams gave Harlan & Hollingsworth the Atlantic Coast Shipyard championship. With it came the Coxe Trophy, a 30-inch-high silver loving cup donated by William G. Coxe of the Emergency Fleet Corporation. This final, stirring game was also the brightest moment in the league’s brief history.

The First World War ended with the armistice on November 11. Many shipyards downsized or closed by the following spring. The Delaware River Shipbuilding League briefly fielded six amateur teams before folding in 1919. Shoeless Joe Jackson and Lefty Williams both returned to Charles Comiskey’s big-league club in Chicago, where their names would be forever tarred by the Black Sox Scandal.

JIM LEEKE is the creative director of Taillight Communications. He contributes to the SABR Baseball Biography Project and has written or edited several books on American and military history. His latest book is “Ballplayers in the Great War.” He is also the author/editor of several books on Civil War and naval history.

Notes

1. “Poor Rules May Hamper Shipbuilders’ Baseball,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, May 13, 1918.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. “Joe Jackson Must Resign in Two Weeks,” Washington Times, May 13, 1918.

5. “Joe Jackson to Be Shipbuilder; Quits White Sox,” Indianapolis Star, May 14, 1918.

6. “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1918.

7. “Major Kolnitz Former Player Defends Jackson,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, February 6, 1919.

8. “Little League Furnish Lots of Excitement in Week-end Baseball Games,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, May 20, 1918.

9. “Pusey & Jones Here Saturday,” Chester Times, June 12, 1918.

10. Lewis Lee Arms, “Huggins Sounds Warning of ‘Ship Building’ Menace to Game,” New York Tribune, May 15, 1918.

11. “Shipyard Players Do Not Camouflage,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1918.

12. Ibid.

1.3 “Little League Leaders Suffer Severe Setbacks; Southampton Swamped,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, June 17, 1918.

14. “Ship League Game Will Feature Schedule in Minor League Circuit,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, June 22, 1918.

15. “Lansdowne Looms Strong as Winner of the First Half Main Line Pennant … Chester Chases ‘Lefty’ Williams,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, June 24, 1918.

16. “Sun Ship Trims Chester Outfit … Bender Does the Trick,” Chester Times, July 8, 1918.

17. “Hog Island Ball Nine Only Half Game From Lead in the Ship League,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, July 8, 1918.

18. “Chester Wins Thrilling Game From Hog Island,” Chester Times, July 15, 1918.

19. “Thirteenth Scheduled Contest on July 13 a Hoodoo for Lupton… Chester Looks Like a Winner in Ship League,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, July 15, 1918.

20. “Ruth Is Peeved But Babe Will Pitch for Red Sox,” Auburn (New York) Citizen, July 10, 1918.

21. Robert W. Maxwell, “Reprieve by President Until October 15 Only Can Save Major Leagues … Few Soft Jobs Left—Men Must Work Like the Others,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, July 20, 1918.

22. Robert W. Maxwell, “Thrills of Old Days of Baseball Revived in Shipyard Circles,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, July 15, 1918.

23. “Sun Wallops Chester Ship,” Chester Times, May 31, 1918

24. “‘Little League’ Ball May Soon Prove the Center Attraction,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, July 22, 1918.

25. “Chester Loses Protest Game,” Chester Times, July 25, 1918.

26. “Delaware River Ship Title Still Up in Air on Players’ Eligibility,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, August 12, 1918.

27. Robert W. Maxwell, “Triple Tie in Shipyard League Will Be Broken by End of the Week,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, August 16, 1918.

28. “Chester Loses to ‘Officials,’” Chester Times, August 23, 1918.

29. “Harlan Team Is Ship Yard Champ,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 29, 1918.

30. “Harlan Trims New York Ship,” Chester Times, August 29, 1918.

31. “Standard Shipyard Nine Is Defeated,” New York Sun, September 8, 1918.

32. “Harlan Triumphs Over Standard,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8, 1918.

33. “Harlan Wins Coxe Trophy,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, September 16, 1918.

34. “Jackson’s Homers Defeat Standards,” New York Sun, September 15, 1918.

35. “Joe Jackson Bats Harlan to Title,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 15, 1918.