The Diamond Stage: Herb Hunter’s 1922 Tour of Japan

This article was written by Adam Berenbak

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

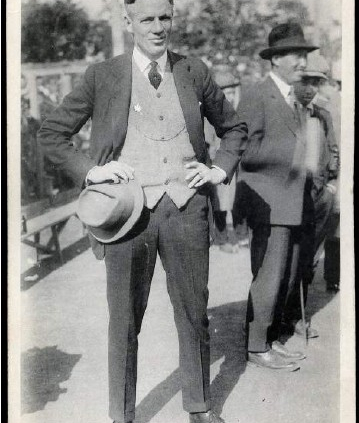

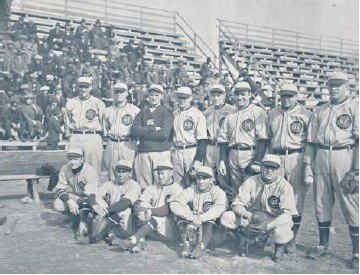

The 1922 All-American team (Rob Fitts Collection)

THE PLOT

The Polo Grounds. New York’s National League champs were on the verge of beating the mighty Yankees for the second year in a row. The 1922 World Series was once again a series in one park, as each game for the past two years had found a home at Coogan’s Bluff. As the triumph neared, Herbert Hunter, a former Giant attending the game, received a cablegram inviting him and the stars of the Series on a tour of Japan. Eager to capitalize on this moment, he recruited several Yanks and Giants, including the dashing George Kelly, to make the trip across the Pacific. Little did they know that they had just been swept up in an international plot to corrupt baseball, a plot not too distant from the Black Sox conspiracy that had nearly ruined faith in the great game.

Luckily for the history of the sport, this was not the truth of the 1922 tour of Japan, nor a plot in any sense other than fictional. The United Pictures Company had assembled a team of actors, both American and Japanese, as well as a loose script about an international conspiracy plot, to travel with the group of major-league all-stars, assembled by Hunter, during their trip overseas.1 Known officially as the All-American Baseball Team but often called the Herb Hunter All-Stars, they sailed across the Pacific after the 1922 season to face college and club teams that represented the height of Japanese talent. In addition to the professional actors, the American and Japanese ballplayers portrayed themselves in the film, participating in the unique experience of acting on two stages at once—in front of the crowds that gathered in Japanese ballparks as well as future crowds in theaters. It might be said that somewhere between fact and fiction lies the truth, and while the tour did not produce the kind of melodrama filmgoers would be eager to view, the games generated their own drama and myths, straddling that line between fact and fiction in the legacy of international baseball.

VANCOUVER

The Canadian Pacific Railway train number 1 arrived in British Columbia on October 17, 1922, carrying with it the team of major leaguers set to sail for Japan and begin a tour of baseball diplomacy. On the 19th the Vancouver weather held and the touring pros, led by Herb Hunter, opened their trip with a 16-1 walloping of Ernie Paepke’s local squad, providing a thrill to a crowd that had little access to major-league ball as well as a proper warm-up prior to the long boat ride to Japan.2 During the game, George Kelly, Irish Meusel, Joe Bush, and Fred Hofmann all saw playing time. Because all four had participated in the recent World Series, this technically broke the rules against Series stars barnstorming together.3 However, due to the pickup nature of the game, neither the press nor the players, and especially not the fans, seemed to care. The team boarded the Empress of Canada for Honolulu immediately after the game.4

Once aboard and on their way, the team received a telegram from Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, hired as commissioner two years prior to clean up the game wrecked by what has become known as the Black Sox Scandal. Reports had reached Landis that the barnstorming rules he guarded with such ferocity had been broken. Just the year before, he had chastised, suspended, and fined Babe Ruth for similar barnstorming infractions. He was furious, especially after only reluctantly giving Hunter permission for the tour.5 The tourists communicated with home via Bob Brown, sponsor of the Vancouver game, to whom they messaged a wireless reply to Judge Landis’s barnstorming complaint. Brown in turn sent an explanation over the wire assuring Landis that there was no intentional rule-breaking and that the entire experience fostered nothing but goodwill and economic possibilities in the Northwest.6 What went unmentioned in the press was that the game was not on the printed schedule, and it was probably the unscheduled barnstorming that added to Landis’s ire. Landis made no reply but was reported sleepless over the incident.7 His objections to barnstorming, along with his reported racial prejudice, combined with the events of the 1922 tour to shape the relationship between US and Japanese baseball for the next decade.8

Tour organizer Herbert Harrison Hunter had been a professional ballplayer since 1914, and signed with John McGraw’s Giants in 1915. Though he had been touted as a sure-bet prospect, Hunter was never able to fulfill those promises in New York or anywhere else in the big leagues. He had first made his way to Japan as part of the 1920 Gene Doyle tour that featured primarily Pacific Coast League players.9 An eccentric among eccentrics, and more of an entertainer on baseball’s stage, Hunter was always a dandy (to McGraw’s consternation and confusion), and enjoyed sticking out, wearing “a fresh chrysanthemum every day” and touring the nightlife of Tokyo as a celebrity.10 During the 1920 tour, Hunter began coaching the Waseda University nine.11 He seemed to enjoy the way the students looked up to him; he treated them to elaborate dinners and allowed them to worship him.12

He found work back in the States in 1921, playing the majority of the year in the South Atlantic League before an end-of-season call-up to the St. Louis Cardinals. In the fall Branch Rickey released him in support of his endeavors in Japan.13 Though Hunter, bom in Boston on Christmas Day 1895, had played in only 39 games over four seasons with the Giants, Red Sox, Cardinals, and Cubs, his major-league experience, however brief, was highly valued in Japan. In the winter of 1921 and into early 1922, Hunter returned to Japan to coach both Waseda and Keio Universities and developed a friendship with the “father of Japanese baseball,” Isoo Abe.14

With Abe’s help, a sponsorship by Mariya Sporting Goods, and the backing of the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper company, Hunter sought to arrange for a group of major leaguers, including Babe Ruth, to tour Japan after the end of the 1922 season.15

Having witnessed the unrealized potential of the 1920 Doyle tour, as well as the value in the promise of Ruth, he knew the revenue was there. And it wouldn’t hurt to align himself with Ruth, the most popular player in the world, to achieve his financial and celebrity ambitions. After spending the whole winter in Japan, he sailed back in February of 1922 with a mission to build a roster, armed with a guarantee of $50,000, though it would be only to cover expenses.16 Hunter envisioned this as the first of what would be annual tours, with him at the center, his mission to promote himself as much as to establish regular international competition with a real “world series.”17

Although Hunter had also worked with Keio as well as other teams that would eventually form the Big Six University system, it was his relationship with the Waseda team that played the biggest role in getting the first real major-league tour of Japan under way. Waseda was eager to become the dominant team in Japan as well as the foremost ambassador of the Japanese game. Between the beginning of 1920 and the All-Stars’ visit in the fall of 1922, the team had faced US competition seven times on both sides of the Pacific.18 Instrumental in their drive were Abe, who had founded the Waseda team and had led the first-ever transcontinental tour when his team traveled the US West Coast in 1905, and Chujun Tobita, a man on a mission. Tobita had played with the Waseda nine back in 1910 when the University of Chicago had beaten them soundly, and the loss inspired the second baseman. Now the manager of Waseda, he drove the team with his famous “death training,” developed to hone the skills and spirit of the young players. Success, in part, meant beating Chicago, and “[i]f the players do not try so hard as to vomit blood in practice, then they cannot hope to win games.”19

With Waseda’s support, the backing of the Mainichi Shimbun, a tentative agreement from both American League President Ban Johnson and Landis that goodwill tours would benefit the game (as long as its participants conducted themselves as diplomats and nobody got injured), and even the support of President Warren Harding, who noted the tour’s “real diplomatic value,” Hunter assembled an all-star squad for the 1922 tour.20

But first a roster would need to be constructed. Rogers Hornsby, Harry Heilmann, and Frank Frisch topped Hunter’s list, but all of his backers in Japan were especially pining for home-run hitters Babe Ruth and George “High Pockets” Kelly. Near the height of his fame, Ruth was a draw everywhere he went, and Japanese fans reportedly clamored for a chance to see him in person—something that didn’t happen for another 12 years. Ruth proved to be unattainable, and most of the others declined for various reasons—even an invitation to Art Nehf that was initially accepted fell through when John McGraw requested that he stay stateside.21

In the end, Hunter secured the 1921 National League home run king George Kelly and put together a team featuring members of the 1922 World Series competitors. Included with Kelly were fellow Giants Casey Stengel and Irish Meusel, along with Waite Hoyt, Fred Hofmann, and Joe Bush from the Yankees. Also on the team were future Hall of Famer Herb Pennock, Amos Strunk, Brooklyn outfielder Bert Griffith, Luke Sewell, Riggs Stevenson, and Bibb Falk. Rounding out the group was John “Doc” Lavan, Hunter’s ex-teammate on the Cardinals.22 The agreement with Landis included a clause that the players would receive no 1923 contract until they reported to spring training in good health after returning from the tour.23 New York Sun sportswriter Frank O’Neill joined as an organizer as well as reporter, along with George Moriarty, who was along as much to be the eyes and ears of Landis as umpire.24 It may have been Moriarty who had reported the barnstorming infraction, but nonetheless his role seemed to be keeping an eye on the proclivities of some of those players prone to take a drink outside the confines of Prohibition.25 Some of the organizers’ and players’ wives accompanied the team, a request made in light of the 1920 tour’s unruly behavior.26

After arriving in Yokohama on the last day of October, the Americans checked into the Tokyo Imperial Hotel. The hotel was one of the few structures to survive the great earthquake that struck Japan in September of the following year. That disaster, known as the Great Kanto Earthquake, devastated Tokyo and led to fires and tsunamis that killed more than 100,000 people.

Japan’s fortunes had fluctuated since the end of the Meiji period, a decade prior to Hunter’s tour. The silk market, and the stock market along with it, had crashed in 1920, and the country’s place on the world stage was precarious.27 Tension between the United States and Japan was high as arguments were about to begin in front of the US Supreme Court regarding barring immigrants of Asian descent from becoming naturalized American citizens.28 The importance of the diplomatic aspect of baseball tours grew as these tensions grew, and the 1922 tour proved how successful the tours could be. This diplomatic endeavor was showcased on the baseball diamond at the Shibaura Grounds in Tokyo’s Minato ward.

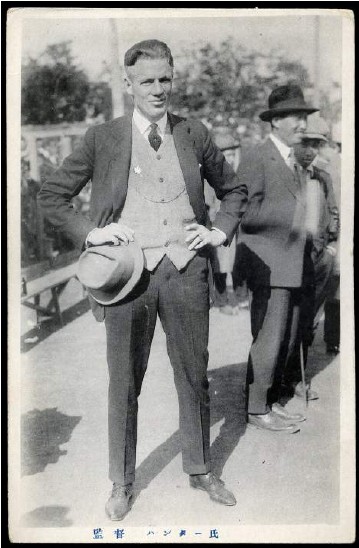

Herb Hunter on the tour of Japan (Rob Fitts Collection)

THE GAMES

Competition finally got underway on November 4 in a game between Hunter’s All-Americans and Keio University at the Shibaura Grounds. Built by Kiyoshi Oshikawa, a former Waseda player and the founder of the Nihon Athletic Association, the diamond at Shibaura was the players’ home for the weeks they were in Tokyo. The team practiced there daily from 10 until noon and used the field for most of their games.29 Keio’s captain, Kazuo Takasu (who later became the first manager of the Nankai Hawks) had befriended Hunter during the previous year when Hunter was coaching the Japanese teams.30 Keio featured shortstop Shinji Kirihara, a future team captain and Hall of Famer credited for reviving the Keio-Waseda rivalry before perishing in World War II, and Kyoichi Nitta, who shared both pitching and catching duties but faced the Americans as the ace of their squad.31

Umpired by George Moriarty as well as local umpire Daisuke Miyake, the game set the tone for many of the games on the tour, with the Americans shutting out Keio, 6-0. Herb Pennock took the mound for the United States and immediately gave up a leadoff double to Kirihara before settling down to allow five hits over nine innings. For Keio, Nitta gave up two triples and a wild pitch in addition to a monster home run by Bibb Falk that rolled all the way to the clubhouse on the other side of the grounds.32 Despite getting hit hard, the visiting tourists praised Nitta and his spitball, saying he “pitched good ball.”

The following day at 2 P.M., the All-Americans faced Waseda University with their ace Goro Taniguchi on the mound. Taniguchi, another future Hall of Famer, was favorably compared to White Sox pitcher Dickie Kerr by the visiting Americans, due not only to his speed but also his assortment of breaking pitches, including his “change of pace which baffled” the American hitters.33 He scattered eight hits while his teammates scored the only run that was tallied against Hunter’s team during the first six games of the tour. Shortstop Tadashi “Teddy” Kubota, whom Herb Hunter had described as the best shortstop he had ever seen, drove in the sole run in the third with a smoking liner off Bullet Joe Bush. That, however, was not enough to make up for the four runs eked out by the Americans, all on singles.34

Midweek practice games against Meiji along with instructional sessions with some of the Keio and Waseda squads filled up the tourists’ time. They spent time in the lobby of the Imperial Hotel fielding questions from the university ballplayers on pitching methods and philosophy.35 It’s possible that an underclassman on the Meiji squad named Shunichi Amachi may have been there too, paying attention to the forkball grip of Joe Bush so he might teach it later to Shigeru Sugishita, who became known as the God of the Forkball in Japan.36

During the first week of the tour, Doc Lavan was not in the lineup. His absence was variously explained as being so sick that he would have to leave the tour, reeling from a weeklong case of sea sickness, or ailing from “old injuries.”37 Whatever the cause, the man they called Doc because of his medical degree from the University of Michigan, finally appeared in the Saturday game against Waseda. Also making his tour debut against Waseda was Casey Stengel, who had ridden the bench the previous weekend, possibly due to the strained muscle that had kept him sidelined during most of the World Series.38 What wasn’t reported was whether Japan’s lack of prohibition laws affected any of the players, though there were vague rumors of bad behavior.39 Herb Hunter, there primarily to organize and manage, ended up playing in nearly all of the games.

Prior to the November 11 game, Stengel, Bush, and Bert Griffith couldn’t resist making their own stage. The three performed “their noted comedy act before the grandstand” to a crowd roughly half the size of the previous weekend’s turnout, due primarily to a cold snap in Tokyo. Their clowning may have been the only fun the frozen fans had, as Pennock proceeded to mow down the Waseda nine, striking out 10 and allowing only two singles over the full nine innings. Waseda starter Aiichi Takeuchi, a first-year student fresh from an appearance in the 1921 Koshien high-school tournament, was driven from the mound in the fourth, though his replacement, Goro Taniguchi, did not fare much better. In all, they gave up 19 hits and 13 runs to the US team, including home runs by Riggs Stephenson, George Kelly, and a fully recuperated Doc Lavan.40

The next day, according to The Sporting News and other US-based media, Waite Hoyt no-hit the Keio team.41 Yet initial reports of the game in Japan show that after giving up nothing but a sixth-inning walk, Hoyt allowed a scratch hit by second-string third baseman Shoichi Takagi in the eighth. Although the American papers saw it as an error, Takagi hit a ball over Hoyt’s head in front of second base, and though Hunter dived for it he couldn’t hold on. Takagi was awarded first base, as well as a hit in the box score published in the Japan Advertiser. He then stole second but was caught off the bag for a double play. Hoyt pitched a one-two-three ninth, and the 20 hits and 12 runs his teammates had compiled off Kyoichi Nitta, including another homer from Falk (who hit for the cycle), led to a comfortable American victory.

SHIBAURA TO TOSHO-GU AND BACK

Nestled in the mountains north of Tokyo is the small city of Nikko, which, in addition to scenic views and multiple onsen (hot spring spas) is the gateway to Nikko National Park and Tosho-gu Shrine. The park was well known as a destination for visiting Westerners, and the traveling ballplayers spent the next few days visiting the shrines and hot springs along with hiking before returning to the comforts of the Imperial Hotel and the thrill of the diamond stage.42

On November 15 at the Yokohama Municipal Park, the Americans faced off for a second time against Meiji. Up front in the stands was Theodore Roosevelt’s son, Kermit, in Japan on a tour of his own, yelling “bully!” as he cheered on Tairiku Watanabe, the team’s ace.43 The All-Americans won handily, 11-0, before adjourning to the home of Ryozo Hiranuma. A Keio graduate who after World War II presided over the Japanese Olympic Committee, Hiranuma hosted a dinner and party that featured, according to the local press, “Occidental dancing.” Golf as well as more social occasions followed, as they were invited to a reception at the Viscount Shibusawa’s home the next day before finally having a day to rest up for the last slate of games in Tokyo.44 Rumors of “at least one of the boys as a boor” surfaced as well.45

Back on the Shibaura diamond on Saturday, November 18, Joe Bush shut out the Tomon Club 12-0 with heavy run support from George Kelly’s home run and Irish Meusel’s triple. The Tomon Club, made up of Waseda alumni, was fortified with several current Waseda players, including Goro Taniguchi and Teddy Kubota. Tomon could only string together three hits with no runs, but one of them was walloped by Katsuo Tanaka, whom both the visiting players and press insisted on calling “Babe Ruth” Tanaka. The title was not hyperbole, as he became one of the heaviest-hitting college players of all time and ended up in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. Taniguchi looked less sharp than in his previous start, giving up 20 hits against two strikeouts, but was spared an extra run when Tanaka threw out Amos Strunk at home.46

There were rumors in the press that the Mita Club was recruiting a ringer for its coming game against the Americans. Hideo Mori, the well-known catcher for the Diamond Club who during the previous year had teamed with Mita Club ace Michimaro Ono to form “the strongest battery in the country,” was scheduled to work behind the plate for Sunday’s game.47 It was the first hint that the final contest at Shibaura would prove the most dramatic moment of the tour. Ono, who had been the ace of the Keio team only a few years before, was to be on the mound for Mita, which fielded a mix of current and former Keio players. One of those former players was Zensuke Shimada (who had played under the name Nenosuke Fukuda against the 1908 Reach All-Americans and the University of Wisconsin in 1909), regularly a catcher but playing third base due to Mori’s place behind the plate.

Hoyt opened the game by striking out the first two batters but then Shimada snuck a home run just over the left-field wall, the first four-bagger hit against US pitching during the tour. It was the beginning of a poor day for the Yankee ace. Without his best stuff, Hoyt did not get much help from his fielders, who allowed Mita to score six runs in an error-filled third. But the real star was Ono, whose breaking pitches broke in all the right places, improving inning to inning with expert pitch calling by Mori. Bibb Falk, who seemed to hit everything he had seen since arriving in Tokyo, was the only American to solve the great Ono—garnering three of the six American hits. In the end, Mita outhit and outscored the US team in the 9-3 win. It was the first time a Japanese team had ever topped a visiting professional team.48

Yet the media had a different take on the game. The Yomiuri Shimbun reported that Hoyt and his teammates had intended to offer a diplomatic bone to the Mita Club in the opening innings before ultimately securing a win, but that the cold weather and bad luck allowed the game to slip away from them. The Kokumin Shimbun was blunter, claiming the Hunter All-Stars had purposely lost to ensure a larger attendance in future games, and that such a tactic amounted to “an insult to the Mita club.”49

These stories made their way into the American press, which were then interpreted through a racist predisposition that considered people of Asian descent naturally inferior to Western men. As a result, the loss was then framed as intentional on the part of Hunter and company.50 Yet George Moriarty seemed convinced the loss was the result of Hoyt’s “bad arm which resulted from excess work in teaching pitching tricks to the college hurlers when the weather was none too inviting,” and Ono’s stellar pitching.51 The original report in the Japan Times concluded Hunter’s squad was simply unprepared against a superior battery that was playing its best on that day.52 In other words, the kind of possibility one finds in any baseball game. However it was interpreted, the victory shaped the perception of international play on both sides of the Pacific for the rest of the decade.

That day at Shibaura proved to be high drama on the silver screen as well as the diamond. The baseball film that had begun production back in New York found its own drama that was vastly different from Ono’s great performance. In the script, George Kelly did not appear in the final game—he had been kidnapped by nefarious henchmen who had offered him a bribe to throw the games against the Japanese contingent. He was said to have “free[d] himself just in time to rush to the diamond near the end of the crucial game and win the series for the American team by a timely pinch hit.”53 It was the narrative the Americans had hoped for. There is no evidence that the movie was ever released, but the drama on the actual diamond against Mita ensured that the Hunter tour would last longer in memory than any drama in a lost film.

WESTERN JAPAN

After the Mita game, the Americans left Tokyo out of Yokohama port on November 20, sent off by a gift-toting crowd of admirers wishing them a safe trip to Kobe.54 It took several days for the party to sail around Wakayama into Osaka Bay, find a berth at Kobe port and travel inland 30 kilometers to Takarazuka, home of the renowned Takarazuka Revue. After another day of rest and relaxation, the All-Americans played their first game outside of Tokyo on November 23. They once again met the Keio nine, facing Kyoichi Nitta and his spitter for the third time. He had a tough time with the major-league hitters, giving up 14 hits, including four homers, two by Amos Strunk. Nitta wasn’t helped by his defense, which committed seven errors. Herb Pennock shut down the Keio hitters and came away with a 14-0 victory.55

The next day at Takarazuka, Michimaro Ono faced off against Hoyt in a rematch of the much-discussed Mita loss at Shibaura a week before. This time Ono, pitching for the Daimai Club (the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun’s company team), did not have quite the same stuff, and gave up 20 hits to go along with 10 errors committed behind him. However, Hoyt was similarly owned by the opposition, giving up 13 hits and 5 runs.56 The team traveled back across Osaka Bay for a game at the Naruo Grounds on the 27th, scoring 12 runs on three straight homers in the third and a run in each inning thereafter.57 The Star Club could put only one on the board, on an RBI double by Waseda alumni Shizuo Takamatsu, in a game that did not last even an hour. Perhaps the teams were eager to get back across the bay for a 120-guest banquet held at the Oriental Hotel in Kobe.58 The large crowd gave a standing ovation to Hunter after he was introduced by host and toastmaster D.H. Blake, an expatriate businessman and a supporter of college baseball.59

Hunter’s tourists next made the 75-kilometer journey, following the path of the Yodo River from Osaka to Japan’s old capital, Kyoto. There they played two games against assembled teams at the Okazaki Park in the shadow of the Heian Shrine. In the first game, the Americans rapped out 16 hits and were aided by eight errors by the All-Kyoto nine in a 12-3 victory.60 On the first day of December the All- Americans hammered the Kyoto all-stars again, 18-0, as no Japanese runner reached third base.61

The next day the Americans were back in the Osaka Bay area for two more games at Naruo. The first game saw the Hunter All-Stars take on the best players in Western Japan, the All-Kwansai team. Herb Pennock once again pitched well in a 12-3 victory.62 In addition to facing their nemesis Ono again, one of the pitchers the Americans faced that day was young Shinjii Hamazaki. The 5-foot-l Hamazaki may have been one of the shortest players in the history of the game, but he was also one of the most durable. After pitching for Keio University, Kobe, and the Diamond Club, he played for the All-Japan squad in both the 1931 and 1934 US tours before taking a break from baseball until after World War II. Starting in 1947, the 45-year- old served as player-manager of the Hankyu Braves and won his final game on the mound in 1950 at age 48. He continued as manager of the Braves through 1953 and later led the Takahashi and Tombo Unions and Kokutetsu Swallows before being enshrined in the Hall of Fame in 1978.63 He is also well known for appearing on a famous cover of Yakyukai magazine alongside O’Neal Pullen of the Philadelphia Royal Giants during their 1927 tour of Japan.64 Assisting him behind the plate was Hideo Mori, the star catcher who had helped Mita upset the All-Americans on November 19.

The next day, Sunday, December 3, a combination of Diamond Club and Mita Club players formed an All-Japan team to face Joe Bush and the US contingent. It was the final time Hunter’s team faced Ono, and he again lacked the magic that he had during his early victory. The tourists took it, 10-0.65

Before setting sail for Korea and China, Hunter’s team played a few more games in Kobe. On the Monday afternoon after facing Ono, they soundly beat the Kobe Commercials, 17-5, at the Kobe Recreation Ground. The next day, December 5, Joe Bush slammed four homers in a 20-3 victory over the Kwansei Gakuin University nine.66 Though most reports of the tour cite this as the final game, the Americans managed one more victory as they traveled westward, a 16-5 win over the Nakajima Mining team in Iizuka before sailing for Korea.

Hunter then led his crew to the Chosen Hotel in Seoul, where the team played the All-Korean team at the South Manchuria Railway grounds at Yongsan.67 A brief stop in Shanghai left time for two quick games, a 19-3 victory over the Shanghai Club and a 16-1 win over the Hongkong Club, before the Empress of Asia sailed for the Philippines. As the ship left port, the players waved to the large crowd that had assembled to see them off. When they arrived in Manila the team faced off against clubs made up of expatriates and US military personnel at Fort Mills as well as against a tough team of Filipino employees of the Manila Street Railway, which resulted in a close game.68 The steamer President Jefferson carried them to Japan for the New Year before cruising back across the Pacific in early 1923.69

HONOLULU AND HOME

Nuuanu Memorial Park lies just outside the downtown Honolulu limits. On January 23, 1923, Hunter and the touring ballplayers, along with local dignitaries and members of the Cartwright family, visited the park to lay a wreath in a ceremony honoring Alexander Joy Cartwright, at that time known as the father of baseball. The ceremony was the last diplomatic mission for the tourists.70 Their stay in Hawaii included several games against local teams, including a doubleheader at Moiliili Park in which the All- Americans beat the Japanese Hawaiian Asahi 17-5 and the All-Chinese 16-0, and later the Braves, 12-0.71 The final game of the tour was at Moiliili against Gusty Lozier’s Wanderers on January 24, a 6-1 victory for Hunter and his team.72 Local fans were thrilled to watch Hunter’s All-Americans after feeling cheated by the visiting 1920 Doyle All-Stars, which had misrepresented the magnitude of its star power.73 This time, the real stars had arrived. The next day, they boarded the T.K.K. Korea Maru for San Francisco, where they had hoped to squeeze in one more contest against a team of San Francisco police officers. However, despite an exchange with Hunter in which he praised the tourists, Judge Landis turned down the request for the game, setting the stage for more rejection to follow.74

The Mita loss, as well as the flaunting of his barnstorming rules in Vancouver, seem to have influenced Landis’s decision to disallow further international barnstorming, preventing Hunter from continuing his mission. The Mita loss in particular fueled Landis’s well-documented prejudices. “For Landis, the loss represented a desecration of the supremacy—and perhaps the integrity, if it was indeed a thrown game—of white American manhood for which the game of baseball stood,” concludes historian Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu.75

These views, combined with the Great Kanto Earthquake of September 1, 1923, which devastated the country’s infrastructure, took countless lives, and interrupted domestic sports, played a large role in limiting international competition at the major-league level. Over the next decade there were tours by college, Japanese American, and African American teams, as well as a women’s ball club, but no American or National Leagueteams went to Japan.

After the 1923 season, Hunter proposed a barnstorming tour of Canada, which featured Harry Heilmann, Rogers Hornsby, and other stars not involved in the 1923 World Series, which seemed to appease Landis. But the tour never came to fruition.76 He also continued his travels to Japan as a coach and organizer. But his dream of annual tours of major-league competition were thwarted by Landis, and aside from a visit he arranged with Ty Cobb in 1928, it was not until 1931 that he would succeed in organizing another sanctioned major-league tour.77 By then Herb Hunter had begun to fade into the background, a victim of his own eccentricities, which allowed Lefty O’Doul to take over as the primary baseball ambassador to Japan by finally delivering Babe Ruth in 1934. Hunter continued to straddle the worlds of entertainment and baseball just as he straddled the worlds on each side of the Pacific, organizing other international sporting endeavors and even attempting to organize a football tour to Japan, but by the end of World War II, he was no longer in the diplomacy business.78 So, like a lost film, Hunter’s 1922 tour, as well as his grand plan to be the center of the diamond stage and true baseball ambassador, would persist only in memory as an influence to future ambassadors of the game. But he cemented his place in the core group of “baseball ambassadors,” along with Lefty O’Doul, Isoo Abe, and Cappy Harada—men who brought the United States and Japan closer together through the mutual love of baseball.

ADAM BERENBAK is an archivist with the National Archives Center for Legislative Archives in Washington, DC. He has been a member of SABR for over a decade and his research focuses on the history of baseball in Japan. He has published articles on Japanese baseball in the SABR Baseball Research Journal and on the blog Our Game, curated an exhibition with the Japanese Embassy’s Cultural Center in DC, and contributed to a number of articles and books. He has also published several essays on other baseball topics in the Baseball Research Journal, Prologue, and Zisk, and he curated an exhibition on tobacco cards in conjunction with the Museum of Durham History and the Durham Bulls Athletic Park. Besides this book, his work was featured in a SABR book on Jackie Robinson.

NOTES

1 “All-American Baseball Stars Enact Roles of Movie Actors,” Japan Advertiser, November 19, 1922: 14.

2 “Ernie Paepke to Lead Local Nine,” Vancouver Sun, October 18, 1922: 8; “Vancouver Ball Fans See Majors in Action,” Vancouver Province, October 19, 1922: 21.

3 “Landis After All-Stars for Violating Rules Here,” Vancouver Province, November 1, 1922: 28.

4 “Line-Ups for This Morning’s Ball Game,” Vancouver Sun, October 19, 1922: 8.

5 “Landis After All-Stars for Violating Rules Here”; Dan Daniel, “Touring Leaguers Must Remain Fit,” New York Herald, October 21, 1922: 12.

6 “Landis After All-Stars for Violating Rules Here.”

7 “Getting Away from Old Lines,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1922: 4.

8 Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu, Transpacific Field of Dreams: How Baseball Linked the United States and Japan in Peace and War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 122-23.

9 Herb Hunter profile, SABR BioProject. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/herb-hunter/.

10 “Cards’ Utility Player a Spectacular Figure in World of Baseball,” St. Louis Star and Times, February 8, 1922: 15; Ed R. Hughes, “Baseball Invasion of the Orient Breaks Up in Big Blow-Off at Kobe, Japan,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 28, 1921: 7; W.N. Stone, “Baseball Thrills Fans in the Orient, Writes Hunter, Former Traveler Gardener,” Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), January 28, 1921: 15.

11 Hughes: 13.

12 “Miller Here for Preseason Visit,” Arkansas Gazette, February 20, 1921: 13.

13 >”‘Japanese Ball Players Already Approach U.S. Professionals,’ Former Cardinal Says,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 17, 1922: 14.

14 “‘Japanese Ball Players Already Approach U.S. Professionals,’ Former Cardinal Says.”

15 “Arm in Arm for Baseball,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1922: 1.

16 Ed Frayne, “Kenworthy Makes Bitter Attack on M’Credie,” Los Angeles Record, March 16, 1922: 11.

17 “Japan Rapidly Adopting America’s National Game,” Washington Post, May 11, 1922: 17.

18 Kazuo Sayama and Bill Staples, Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers inJapan (Fresno, California: Nisei Baseball Research Project Press, 2019), 177.

19 Robert K. Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth: Baseball, Espionage, & Assassination during the 1934 Tour of Japan (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 169.

20 “Japanese Want to See the Babe,” Lebanon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, April 6, 1922: 9; “Conducting a Proper Tour,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1922:4; “Harding Says Tour of Ball Clubs Will Be of Diplomatic Value,” Shreveport Times, October 6, 1922: 8.

21 James McLain, “Japs Pick Cardinals to Win World Series,” St. Louis Star and Times, April 22, 1922: 11; “Japanese Admire Ruth and Kelly,” Los Angeles Record, March 16, 1922: 11.

22 “American Star Ball Players Ready for Fray,” Japan Times & Mail, November 1, 1922: 8.

23 “Major Leaguers on Tour in Orient Will Not Get Contracts,” Port Huron (Michigan) Times Herald, October 21, 1922: 13.

24 “Tourists Leave Chicago,” New York, October 16 1922: 22; Guthrie-Shimizu, 123.

25 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting , October 19, 1922: 8.

26 “Conducting a Proper Tour;” “Baseball Tourists Start Trip Today,” New York Times, October 14, 1922: 16.

27 Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

28 United States Congress, House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, Japanese Immigration, Hearings Before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, House of Representatives, Sixty-Sixth Congress, Second Session (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1921).

29 Yusuke Suzumura, The Formation of First Professional Baseball Team in Japan, Academia, https://www.academia.edu/29232638, last accessed December 1, 2021.

30 “In Real Peace Conference: Arm in Arm for Baseball,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1922: 1.”

31 Dennis Snelling, Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 184.

32 “Americans Defeat Keio Team, 6 to 0, in First Game Here,” Japan Advertiser, November 5, 1922: 8.

33 Frank F. O’Neill, “Japan Teams Prove Class on Ballfield,” Japan Times & Mail, November 6, 1922: 1.

34 “Waseda Makes Run but Loses, 4 to 1,” Japan Advertiser, November 7, 1922: 10.

35 “American Nine Well Pleased at Reception,” Japan Times & Mail, November 17, 1922: 1.

36 Tyler Kepner, K: A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches (New York: Anchor Books, 2019), 142.

37 “Most Anything in Sports,” Baltimore Evening Sun, November 16 1922: 38; “Americans Sweep Japs Off Their Feet,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1922: 1; “Waseda and Keio Games to Be Last,” Japan Advertiser, November 10, 1922: 10.

38 “Waseda and Keio Games to Be Last.”

39 Frank F. O’Neill, “American Nine Well Pleased at Reception,” Japan Times & Mail, November 17, 1922: 1.

40 “Big Leaguers Slug Way to a 13-0 Win,” Japan Advertiser, November 12, 1922: 8.

41 “Americans Sweep Japs Off Their Feet.”

42 “Yokohama to See U.S. Stars Today,” Japan Advertiser, November 15, 1922: 10.

43 Watanabe went on to a brief stint managing in the inaugural season of the Central League in 1950.

44 Frank F. O’Neill, “Meiji Players Lose Contest to Americans,” Japan Times & Mail, November 16, 1922: 1.

45 O’Neill, “American Nine Well Pleased at Reception.”

46 “Americans Defeat Tomon Team, 12-0,” Japan Advertiser, November 19, 1922: 8.

47 “Americans Defeat Tomon Team, 12-0.”

48 “Americans Beaten in Comedy Display,” Japan Advertiser November 21, 1922: 10.

49 “Tokyo Press Realizes Something Was Wrong,” Japan Advertiser, November 21, 1922: 10.

50 “Better Call ‘Em Home, Judge,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1922: 4.

51 >George Moriarty, “Moriarty Praises Players Conduct on Tour of East,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1923: 3.

52 “Americans Beaten in Comedy Display.”

53 “All-American Baseball Stars Enact Roles of Movie Actors.”

54 “Players Get Send-Off,” Japan Advertiser, December 20, 1922: 10.

55 “Americans Defeat Keio Nine, 14-0,” Japan Advertiser, November 24, 1922: 10.

56 “Osaka Team Loses to Americans 25-5,” Japan Advertiser, November 26, 1922: 8.

57 “All-American Team Defeats Stars Nine,” Japan Times & Mail, November 28, 1922: 8.

58 “Kobe Americans Fete Big League Players,” Japan Advertiser, November 28, 1928: 10.

59 “International Commercial Events,” The Trans-pacific: A Weekly Review of Far Eastern Political, Social, and Economic Developments, Volume 7, September 1922: 77.

60 “Tourists Run Away as Usual,” Chattanooga Daily Times, December 2, 1922: 12.

61 “America Nine Wins,” Japan Times & Mail, December 2, 1922: 1.

62 “Two Victories End Big Leaguers’ Visit,” Japan Advertiser, December 5, 1922: 10.

63 https://baseball-museum.0r.jp/hall-0f-famers/h0f-058/.

64 Sayama and Staples, 1.

65 “Two Victories End Big Leaguers’ Visit.”

66 “Americans Win Last Game by 20-3 Count,” Japan Advertiser, December 7, 1922: 10.

67 “Americans in Seoul,” Japan Times & Mail, December 8, 1922: 1.

68 “Touring Ball Team Wins Another Game,” Victoria (British Columbia) Daily Times, December 23, 1922: 10; “Defeats Fillipino Team,” Grand Island (Nebraska) Daily Independent, December 22, 1922: 3.

69 “Barnstormers Start Homeward Journey,” Richmond Times Dispatch, December 26, 1922: 9; “Ball Players Returning,” Japan Times & Mail, December 28, 1922: 1.

70 “Big Leaguers to be Guests Today of Ad Clubbers,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 24, 1923: 3.

71 “Hunter’s Team Wins,” .Japan Times & Mail, January 24, 1923: 8; “Major Leaguers to Play Braves at 3:30 Today,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, January 23, 1923: 10; Doc Adams, “Coueism Shows at Local Ball Arena as Games Improve,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 24, 1923: 4.

72 Doc Adams, “Leaguers Defeated Wanderers 6 to 1; Best Game of Four,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 25, 1923: 4.

73 Mike Jay, “Hunter Bunch to Do Much to Wipe Away Bad Taste Left by That Last Team,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, January 19, 1923: 8.

74 “Herb Hunter Sends Reply to Landis,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, January 22, 1923: 7; “Landis Puts Ban on Game Sunday,” San Francisco Examiner, February 3, 1923: 29.

75 Guthrie-Shimizu, 123.

76 “Heilmann to Play with Herb Hunter,” Detroit Free Press, September 3, 1923: 10.

77 Fitts, 16.