The Elysian Fields of Brooklyn: The Parade Ground

This article was written by Andrew Paul Mele

This article was published in Fall 2012 Baseball Research Journal

The dictionary defines the word “Elysian” as “something blissful; delightful,”1 and for ballplayers, such a place has existed for 140 years in the city of New York. Brooklyn is one of the five boroughs of New York City and if considered as a separate entity would rank fourth in the country in sending players to the major leagues, behind Chicago, Philadelphia, and the other four non-Brooklyn boroughs combined.2 There is a 40-acre tract of amateur playing fields lying in the Flatbush section—just a fungo hit away from where Ebbets Field once stood—that has been a nexus for the baseball-hungry borough to showcase its youth.

Established in 1869 and named for its original purpose, the Parade Ground has quite possibly produced more professional and major league ballplayers than any such piece of real estate in the nation. It is difficult to ascertain with any degree of certainty which players in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century may have played their early baseball there, but future stars like “Wee Willie” Keeler—who was born in 1872 on Pulaski Street and died 50 years later in a house just a few blocks away—undoubtedly got some playing time at the fabled “Park.” Likely so did Joe Judge, whose 20-year major league career resulted in a .298 batting average, and pitcher Jimmy Ring.

The earliest player that we can be sure played at the Ground was a graduate of Erasmus Hall High School named Waite Hoyt. Hoyt grew up in the Borough Park section of Brooklyn and played his early games at the Parade Ground before embarking upon a major league career in 1918. He tried out in 1913 for his favorite ballclub, but the Dodgers turned him down. Signed by John McGraw of the Giants at age 15, Hoyt spent three seasons in the minor leagues. He did pitch one perfect inning for the Giants in 1918, in which he struck out two, only to find himself in the uniform of the Boston Red Sox the next season. In 1921 he joined his former Red Sox teammate, George Herman Ruth, in New York with the Yankees and his star began to shine. Hoyt won 19 games as the Yanks won the American League pennant.

In the World Series he pitched three complete games, winning two and losing Game Eight on an unearned run, 1–0. In fact, in 27 innings he gave up two runs total, both unearned. He would pitch in six more World Series, winning six games and losing four. He was a Yankee into the 1930 season before being traded to the Detroit Tigers. In 1927, backed by “Murderers’ Row,” Hoyt led the American league in wins with 22 and winning percentage at .759. He lost just seven games that year. After leaving New York, he went from Detroit to the Philadelphia Athletics, then to Brooklyn and back to the Giants. He was with the Pittsburgh Pirates for five seasons before Brooklyn acquired him in 1937. Hoyt was released by the Dodgers after throwing just 161⁄3 innings. He was 0–3, his ERA had ballooned to 4.96, and on that note his big league career came to an end.3 Waite Hoyt won 237 major league games over 21 seasons and in 1969 was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame, one of five original Brooklynites enshrined at Cooperstown.

Waite Hoyt, however, was far more than numbers. A friend and teammate to both Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, he stood with his former teammates at Yankee Stadium on the day that the Iron Horse proclaimed himself to be “the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” He was present when the Babe, dying of throat cancer, said his last goodbyes. Known for his vast store of baseball stories, Hoyt spoke for two hours on the air without notes in a moving tribute to Ruth two days after Ruth had passed away. He authored an oft-quoted book, Babe Ruth As I Knew Him, which Ruth biographer Robert Creamer called “by far the most revealing and rewarding work on Ruth.”4

Upon being released as a player in 1938, Hoyt still had to earn a living. At age 39 he could still pitch, so he signed with a semi-pro outfit called the Brooklyn Bushwicks. He was paid $150 per game.5 The Bushwicks played at a home field in Woodhaven, Queens called Dexter Park, and this was no bush baseball. Major leaguers who had played at the Parade Ground and who picked up some extra money with the Bushwicks included Gene Hermanski, Phil Rizzuto, Bots Nekola, and the Cuccinello brothers.6 Tony and Al Cuccinello were from Long Island City and, along with Nekola, played for the Sanitation Department in the Parade Ground Industrial league. Francis Joseph Nekola was from the Bronx and notched 20 innings of major league pitching before he became a scout for the Boston Red Sox. One of many who spent a good deal of time at the Parade Ground, he signed Chuck Schilling and Ted Schreiber from there, both of whom would go on to the majors. Nekola’s crowning achievement, however, was inking Hall-of-Famer Carl Yastrzemski of Long Island.7

The World War II years took a heavy toll on the country and professional baseball. More than 5,000 players served in the armed forces, but the game went on and several Parade Ground players hit the big time in that era. One of these was Tommy Holmes. Raised in the Bay Ridge section at 57 street off Fort Hamilton Parkway, Tommy played with a neighborhood team called the Overtons, who used a park near his home called Overton Field in addition to the Parade Ground.

In 1945 while playing for the Boston Braves, Tommy Holmes hit in 37 consecutive games, a post-1900 National League record at the time. That season, Holmes led the National League with 224 hits and 28 home runs. He finished second in RBIs with 117 and his .352 batting average made him the runner-up to batting champ Phil Cavaretta of the Cubs. In 11 major league seasons, Holmes hit a collective .302.

On August 20, 1945, Tommy Brown, also of Bay Ridge—who played with the Ty Cobbs at the Parade Ground—became the youngest player to homer in the majors.8 He was only 17 when he belted one against Pittsburgh.

Sid Gordon was a Jewish kid from the Brownsville section who was tailor-made for Ebbets Field and the Dodgers. Always on the lookout for ballplayers to cater to the large Jewish population in Brooklyn, the Dodgers missed this one when the Giants got to him first. Gordon went to Samuel J. Tilden High School and then attended Long Island University. He was signed by Giants scout George Mack in 1938 off the sandlots and made his major league debut on September 11, 1941. Gordon had a 13-year major league career hitting .283 with 202 home runs. Sid was a two-time All-Star while playing for three different teams.

Marius Russo played first base in high school and at Long Island University before taking over the pitcher’s mound.9 He played three seasons with the Newark Bears and five with the Yankees before entering the military in 1944. Russo won Game Three of the 1941 World Series. Larry Napp from Avenue U had a distinguished 24-year career as an American League umpire. The era also produced Saul Rogovin, Bill Lohrman, and Cal Abrams. Andy Olsen and C.B. Bucknor began as players before going on to careers as major league umpires. Brooklyn native Larry Yaffa—who played with Napp and Chuck Connors, future major leaguer and TV star—recalled in his 90th year, “everybody played at the Parade Grounds back then.”10

Following the end of the minor league seasons in September, during the forties and early fifties many professional players appeared in sandlot games. A sampling was the 1–0 duel between Larry DiVita and Jerry Casale on Parade Ground diamond No. 13 which Casale cinched with a home run.11 Casale would go on to play five seasons in the majors.

Milt Laurie was manager of a team called the Parkviews in the early fifties. They played their games at Dyker Park in Bensonhurst and at the Parade Ground. It was Laurie who moved a hard-throwing, left-handed first baseman to the pitcher’s mound. As Sandy Koufax put it, “My sandlot manager, Milt Laurie, was the first to recognize my ability.”12 Koufax threw extremely hard on the sandlots, but struggled with his control, just as he would in his first several years in the majors. John Chino, a Brooklyn sand-lotter remembers facing Koufax at the Park. “What velocity, nobody could catch him, he was so fast,” Chino said. “Holy mackerel,” he recalled thinking at the time, “where did this guy come from?”13

Koufax began as a boy with the Tomahawks, his first team in the Ice Cream League. The league president was a man named Milton Secol who liked to call himself “Pop” Secol. Laurie’s sons, Larry and Wally, who also played for the Parkviews, brought Sandy to that ballclub.

Koufax was, of course, scouted by the many advance men who flooded the sandlot mecca on a regular basis. The Pittsburgh Pirates had a watchful eye on the prospect, but the Dodgers’ Al Campanis was the one who got Koufax’s name on a contract. To dissuade teams from handing out big bonuses, a rule at the time prohibited any player who received more than a $4,000 bonus from being farmed out. Keeping an untried kid on the major league roster for two seasons would take up a valuable spot and deprive the player of minor league seasoning, making most clubs leery of doing it. Koufax signed for $14,000 in December 1954 and joined Brooklyn for the 1955 season.

It was a difficult time for the youngster, who was used sparingly and was usually wild. He did, however, pitch a shutout in his seventh appearance (second start), blanking the Cincinnati Reds, 7–0. In those two mandatory years, Koufax went 4–6 in 100 innings, striking out 60. In retrospect, later historians blame manager Walter Alston for not using the young pitcher more regularly and some believe Koufax would have developed faster and sooner with regular use.14

Alston’s clubs were in pennant races in both 1955 and 1956. The ace of his staff was Don Newcombe, who won 20 and 27 games respectively, backed by Carl Erskine as well as Johnny Podres before Podres went into the Navy in ’56. By 1957 the scenario had been altered. The Dodgers’ last year in Brooklyn would result in a third-place finish and a pitching staff that could have used a boost, but still Koufax was not part of the regular rotation. He threw just 1041⁄3 innings with a 5–4 record. He walked 51 and struck out 122. There were flashes of brilliance. On June 4 he struck out 12 Cubs and had at that point 59 strikeouts in 492⁄3 innings, but it would be 45 days before he got another start. The combination of resentment by veteran players, lack of minor league training, irregularity of work, and pressure he felt from the anti-semitic faction contributed to discouragement felt by the young pitcher, and for a time he considered giving it all up.

Unlike in the major leagues, neither segregation nor anti-semitism was evident at the Parade Ground. Tommy Davis, an African-American from the Bedford Stuyvesant section, when told to be aware of the problem as he entered pro ball, was puzzled by the advice. “Never,” the two time National League batting champion said, “had I ever encountered anything of the kind at the Parade Ground.”15

Davis called Fred Wilpon, later owner of the New York Mets, “one of the best lefthanders at the Parade Ground.”16 Wilpon, like friend Koufax, was a Jewish pitcher from Lafayette High School, and echoed Davis’s words when recalling the experience of playing there. “It was a very special place,” he said. “There was never an incident that I experienced or heard of regarding race or anti-semitism.”17

The scenario continued for Koufax with the then-LA Dodgers until a fateful spring training day in 1961. In a game against the Twins at Orlando, Koufax was scheduled to pitch seven innings. On the trip he sat with catcher Norm Sherry whose advice was to “get the ball over the plate.” In the game he persisted, telling Koufax to “take something off the ball and let them hit it.”18 Inexplicably, Koufax threw even harder when trying to ease up. In seven innings he struck out eight, walked five, and didn’t give up a hit. The ultimate result of the new approach was pinpoint control. Koufax liked to work the outside corner of the plate and he began to hug the black. In 1961, he went 18–13 in 2552⁄3 innings. He struck out 269. He walked just 96. The next year an injury held him to 14–7.

The mold would be completely broken as Koufax put together four incredible seasons. He won 97 games, losing 27. He had seasons of 25, 26, and 27 victories. Three times he struck out more than 300, topping out with 382 in 1965. He averaged just 65 walks a season and pitched 1,192 innings. Koufax pitched four no-hit games in four consecutive seasons; the last in 1965 was a perfect game. He pitched in four World Series and compiled a 4–3 record.

October 2, 1963, the opening day of the World Series, the opposing pitchers were Sandy Koufax and the Yankees’ Whitey Ford. The two had several things in common. Both were fine left-handers, both excelled in World Series play, both were destined for Cooperstown, and both had toed the Elysian mounds of the Parade Ground. (Ford had thrown three perfect innings as a member of the Fort Monmouth Army team while stationed there during the Korean war.)19 Koufax won the opener while striking out fifteen and breaking the record set by teammate Carl Erskine ten years before. He also won Game Four as the Dodgers swept the Yankees in four straight.

After winning 27 games in ’66, the 31-year old shocked the baseball world by announcing his retirement, forced out because of an arm injury. In 12 seasons he won 165 games, 111 in the last five years. In 2,3241⁄3 innings, the kid from Brooklyn struck out 2,396 batters. Perhaps the most succinct description of Koufax’s prowess came from Pirates slugger and Hall-of-Famer Willie Stargell, who said that trying to hit Koufax was like trying “to drink coffee with a fork.”20

In 1972 Koufax became the youngest man ever elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In retirement, Koufax was somewhat elusive. He remained out of the limelight and preferred privacy. But, as broadcaster Vin Scully pointed out, the Brooklyn born-and-bred super-pitcher would forever be associated with the letter K: for Koufax and for strikeouts.

The period from 1947 through 1957 would be known as the “Golden Age of Baseball” in New York City. There were three major league teams and a plethora of terrific sandlot ball throughout the borough, with the Parade Ground being the flagship facility for baseball. These years were probably the most prolific in the prodigious history of this amateur facility. In the first half of the sixties alone, there were a number of men who made the major leagues. Rico Petrocelli would set an American League record for home runs by a shortstop with 40 while with the Boston Red Sox. Joe Pepitone took his bat, glove, and hair dryer to the majors. In spite of his faults—and his own laments that he failed to reach his potential because of them— Pepitone notched 12 seasons in the majors and 219 home runs. On the Parade Ground, he was notable for his skill with the bat, but Frank Chiarello recalls Pepitone had defensive skills, as well. Chiarello had played for Wellsville, New York, the PONY league and recalled a day that Pepi, playing right field, pulled down a Chiarello drive with a running catch in right-center field. A couple of innings later, Chiarello drilled one inside the first-base line and Pepitone, now playing first, made a diving stop. “He took two doubles away from me,” Chiarello lamented, “playing two different positions.”21

In addition to Koufax, the Dodgers had Tommy Davis and Al Ferrara and Joe Pignatano, a roommate of Sandy’s for a time. The Aspromonte brothers, Ken and Bob, were playing in the National League, as were Frank and Joe Torre. Ted Schreiber was with the Mets, Tony Balsamo with the Cubs, and Don McMahon was in the midst of an 18-year major league pitching career. Jerry Casale played a few years with the Red Sox, then moved on to the Angels and Tigers. Second baseman Chuck Schilling put in five years of big league time 1961–65 with Boston. Larry Bearnarth pitched in relief for the New York Mets, 1963–66.

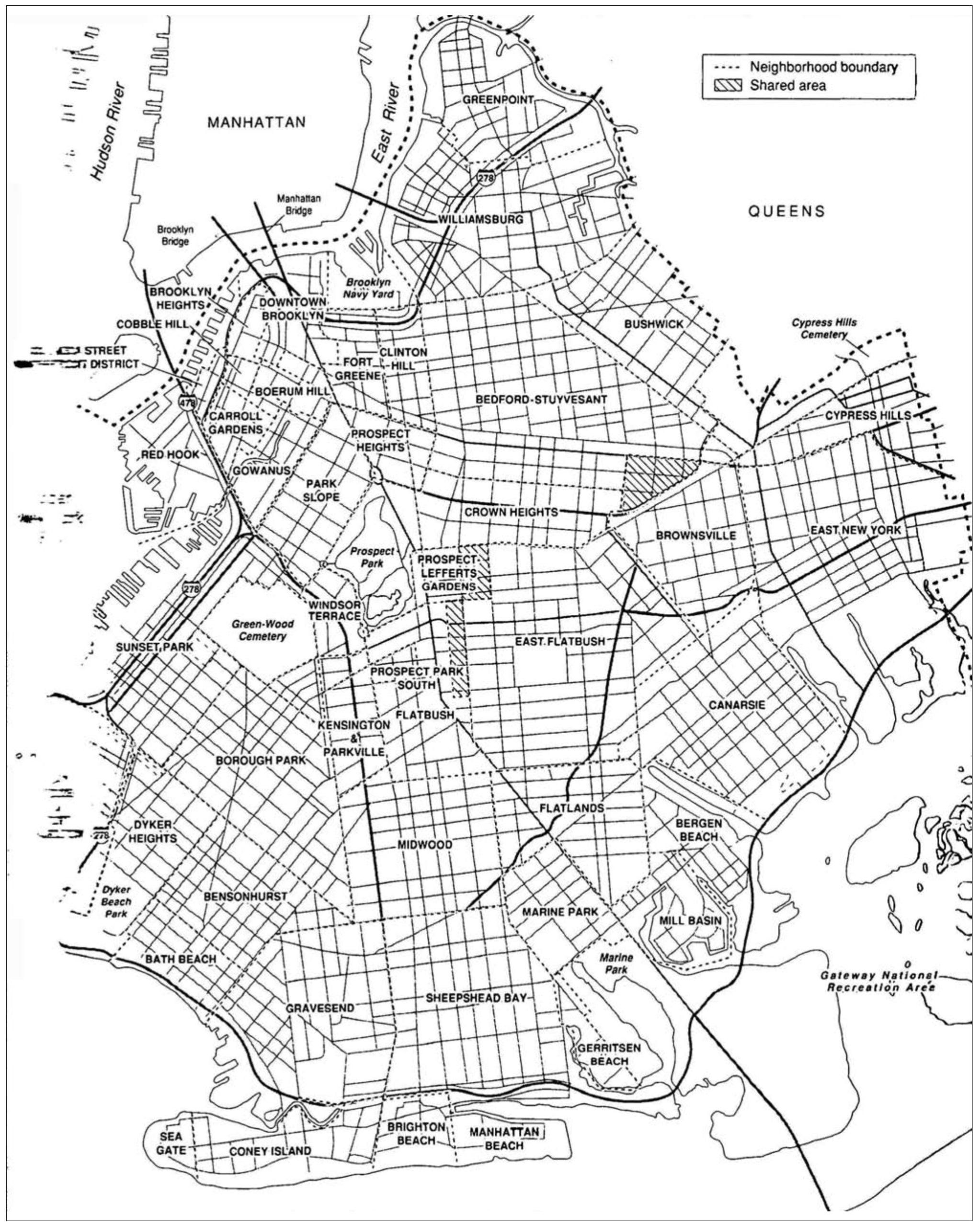

The borough’s quilt of neighborhoods, as mapped in the book The Neighborhoods of Brooklyn by Kenneth T. Jackson and John Manbeck. (Used by permission of Yale University Press)

Parade Grounders were constantly in touch with each other at the major league level. When Koufax defeated Bob Gibson in a 1–0 sizzler in 1961, it was Tommy Davis who homered for the win. According to Jane Leavy, “they celebrated by dancing around the clubhouse crowing: ‘Us Brooklyn boys got to stick together.’”22 Joe Pepitone and Rico Petrocelli once playfully squared off while their respective ballclubs engaged in an on-the-field melee.23

On any given Saturday or Sunday the crowds at the Parade Ground were significant. Of the 13 diamonds, two were enclosed with cyclone fencing. Diamonds 1 and 13 often had as many as 1,000 to 1,500 spectators. They filled the wooden bleachers and lined up along the fencing. They leaned over the four-foot-high center-field fence, 363 feet away from home plate on diamond No. 1, a spot where 15-year-old Terry Crowley was once witnessed to have hit two over in one day.24

At about the time that Koufax was beginning his major league career, another potential Hall of Fame career was being nurtured in Brooklyn. At 14 years old, Joe Torre was already impressing Parade Ground regulars. Vincent “Cookie” Lorenzo, the director of the Parade Ground League, began to herald the chubby youngster with enthusiasm. Joe played third base and first base and pitched for the Brooklyn Cadets. Manager Jim McElroy already had a Torre moment with big brother Frank. In 1949 Frank Torre was the batting champ of the Federation Baseball tournament at Johnstown, Pennsylvania. When Joe took the same honors several years later, they became the only brother combination to boast this accomplishment.25

Young Joe, however, seemed to turn off the scouts because of his weight. They doubted his ability to go all the way, though partisans like Lorenzo and McElroy maintain that Joe’s bat would have done the job and the excess baggage that he carried would melt away with maturity. It was brother Frank who insisted to McElroy that Joe go behind the plate where he thought he would have the best chance.26 One of Joe’s earliest games as a catcher came against a strong Parade Ground club called the Senecas. Prior to the game McElroy approached Ken Avalone, the Senecas catcher and manager, and asked that he run his fastest man when and if the situation called for it.27

Avalone explained what happened. “I sent McCallister on a steal attempt from first. The pitch hit the dirt in front of Torre and kicked off his chest protector and fell in front of him. He grabbed it and caught Earl by a mile.”28 There seemed to be very little to stand in Joe’s way then. The Torre saga was near to being repeated. Frank had signed with scout Honey Russell of the Braves in 1950 and made his major league debut in 1956. The elder Torre, a first baseman, played seven years in the big time and hit .273. A highlight came in the 1957 World Series when Frank hit two home runs. Frank had an enormous influence on his younger brother’s development as a player. He was a stickler for passing on the knowledge and experience he had acquired to his kid brother. The major league tie was strong as Joe spent time in big league club houses and relished the times that Frank brought friends and teammates home for dinner. One teammate was another Brooklyn boy who played at Erasmus Hall and the Parade Grounds, Don McMahon.

The same scout, Honey Russell, who had signed Frank, got Joe’s name on a contract in the fall of 1959 with a bonus of $22,000 included. In 1960, the Braves sent him off to Eau Claire, Wisconsin in the Class C Northern League for Joe’s first taste of the pros. He savored the experience with a .344 batting average, 16 home runs, and a September call-up to the Braves. On September 25 Torre got his first taste of big league pitching when he pinch hit against Pirates left-hander Harvey Haddix. Joe hit a fastball away, up the middle for a single. Assigned to triple-A Louisville the next season, Torre was hitting at a .342 clip after 27 games when an injury to Braves catcher Del Crandall prompted a promotion to the big club. His first time out he caught Warren Spahn. Later that season he was behind the plate when baseball’s winningest left-hander, Spahn, hurled his 300th career victory.

Torre ended the year with a .278 average and ten home runs and finished second to the Cubs Billy Williams for Rookie of the Year honors. In December 1963 Crandall was traded to the San Francisco Giants and Joe had the job all to himself in 1964. That year Torre hit .321, banged out 20 homers, and drove in 109 runs. He led all National League catchers with a .995 fielding percentage. He played in the second of five consecutive All-Star games, there would be eight all told, and the next season he hit 27 four-baggers.

The next year the Braves relocated to Atlanta, opening the season at Atlanta Stadium, a haven for home-run hitters due to the high elevation and thin air. Joe hit 36, drove in 101, and batted .315. Traded to the Cardinals, Torre continued his effective hitting, confirming the belief of his sandlot manager, Jim McElroy, who once opined that Joe’s hitting would carry him to the top regardless of what position he played.29 In 1971, Torre won the National League batting crown with a .363 average and league-leading numbers in hits (230) and RBIs (137). Torre also took home MVP honors for the year. Joe Torre’s 18-year career finished with a composite .297 batting average, 252 home runs, and 1,185 RBIs.

After finishing his playing career, Torre had stints that for the most part were unsuccessful as manager of the Mets, Braves, and Cardinals, with five years in the broadcasting booth sandwiched in between. Joe then signed to manage the New York Yankees for the 1996 season and therein the legend began. During Torre’s first five seasons, the Yankees won four World championships, and during his tenure they racked up 10 American League East titles, six pennants, and twice Joe was named Manager of the Year. Currently fifth on the all-time managerial win list with 2,326 victories, Joe took over the reins of the LA Dodgers for three seasons before accepting the position he currently holds as Executive Vice President for Baseball Operations for Major League Baseball.

Torre’s entire career may harken back to a day in 1959 at the Parade Ground. Early on a summer evening just days before he would sign his first pro contract, the chubby 19-year-old could be seen amid the uniformed Park players clad in white shorts and white T-shirt jogging over the expanse of the 40-acre facility. A long and sometimes arduous trek from Brooklyn’s Parade Ground for Joe Torre has indeed proven a fulfilling experience.

In 1905 a huge edifice was erected at the Parade Ground. Known thereafter as “the Clubhouse,” it contained locker rooms, showers, storage, and offices for the Parks Department, and a card room often exhuding cigar smoke and noisy chatter. Great stone columns rose at the entrance like a Roman colossus and the clacking of metal spikes on the cement steps was as much a sound of the Ground as the crack of the bat. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the park had as many as 21 baseball diamonds overlapping each other to the extent that more than one game seemed to be going on at the same field.30 Wisely, it was reduced to 15 and then to 13 where it remained until the last renovation in 2004. Always reflecting the demographics of the community, the Parade Ground currently contains a mere five fields for baseball or softball. Now there are tennis courts and much space for the encroaching game of soccer.

The clubhouse was razed in the mid-sixties. Old, with cracked cement, warped wooden floors, and rusted shower pipes, it was replaced by a single-story building lacking the character of its predecessor. In the last decades of the twentieth century, the entire area was in much disrepair. Rocks and broken glass marred the fields. To past denizens it seemed as though the local talent would have deteriorated along with the entire complex, but that wasn’t the case. Along came Shawon Dunston, 18 years a big leaguer, John Candelaria, whose family lived in an apartment on Caton Avenue just opposite the Park grounds, close enough for his mom to call him to dinner. Candelaria won 177 games in the majors including a no-hit gem against the Dodgers in 1976. Lee Mazzilli, a Lincoln High School graduate, was a hometown favorite when he played for the Mets, as did pitcher Pete Falcone.

Frank A. Tepedino was a former minor leaguer who played 11 seasons in the Cardinals chain, mostly in the Class D Coastal Plain League and Georgia State League, who finished his minor league career as a player-manager. After returning to New York, he took over the running of an American Legion team called Cummings Post. He saw it as a vehicle for his three sons and several nephews, and they all played for him over the years. His brother’s boy, also named Frank, went from the Legion to pro ball and to the major leagues where he spent eight seasons.

Tepedino, the manager, worked for the NYC Housing Authority and, while always looking to enhance his ballclub, came upon a 14-year-old at the Tilden Projects in whom he saw some very good possibilities. The youth, Willie Randolph, was immediately invited to join the Cummings Post team. Frank’s son Rick played alongside Willie in the infield and recalls him as a “wonderful guy who, even at fourteen, was all business on the field.”31

Randolph was born in Holly Hill, South Carolina, and his family moved to Brooklyn where Willie attended Samuel J. Tilden High School. A star athlete in school and a top sandlot player, Randolph was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates in the seventh round of the 1972 draft. It was after coming off diamond No. 7 on Parkside Avenue that Randolph agreed to a contract. “I signed at field 7,” he said. “The Pirates scout was nickel-and-diming me…and I signed for $5,000. Little did he know I would have signed for nothing.”32

Randolph spent four seasons in the minors beginning in the rookie-level Gulf Coast League and winding up in triple-A Charleston in the International League. In 91 games there in 1975, he hit .339 before being called up to Pittsburgh. Before the next year he was traded to the Yankees and that began a string of 13 seasons in pinstripes. Randolph was a six time All-Star selection, played with two world championship teams in his career, and co-captained the Yankees from 1986–88. Following his stint with the Yankees, Randolph went to Los Angeles, Oakland, and Milwaukee before closing out his 18-year career at age 38 with 90 games for the New York Mets. He hit .276 lifetime, with a .373 OBP, 2,210 hits, and over 1,200 walks.

After retiring from playing, Randolph coached 11 seasons for the Yankees until he was named Mets manager in 2005. He completed that season with an 83–79 record, the first time since 2001 the Mets finished over .500. In 2006, they won the NL East title while tying for the best record in baseball (with the Yanks) at 97–65. The Mets, however, didn’t get to the World Series, losing the seventh game of the NLCS to the St. Louis Cardinals. Randolph was second in the balloting for the Manager of the Year honors. On January 27, 2007, he signed a three-year, $5.65 million contract extension.

But the baseball gods said, “enough.” In 2007 Willie’s Mets stumbled at the finish line in one of the worse collapses in history. With a seven-game lead and only 17 games left to play, the Mets went 5–12 and lost the division to the Phillies. After a slow start in 2008, Randolph was fired on June 17. Perhaps Randolph did not get a fair shake, especially in view of the fact that several key players had lingered on the disabled list for long periods. There were no gripes from Randolph.

In 1981, while Randolph was helping the Yankees to another pennant and being named to the American League All-Star team, Dan Liotta, a local umpire, was calling balls and strikes at the Parade Ground. It was in this year that Danny worked the plate in the last sandlot game that John Franco pitched before signing with the Dodgers. As Liotta remembers it, “Johnny threw an 8–0 shutout.”33 Shortly thereafter, on June 8, he was selected in the fifth round of the amateur draft and signed by Los Angeles. A local scout had this to say about the youthful pitcher while he was at St. John’s University: “Great control, nothing above the knees. Good pitching selection. Far ahead of his peers in setting up hitters and changing speeds. Fastball moves away from right-handed hitters.”34

Franco was scouted by Steve Lembo, whose major league career was limited to 11 at-bats, but who was a Parade Ground star before being a pro, and Gil Bassetti. Bassetti was a pitching star at the grounds before signing with the Giants. He reached the triple-A level before turning to scouting. Both worked for the Dodgers and both evaluated and were involved with the signing of John Franco. Franco played at the fabled Lafayette High School, and then attended St. John’s University where he pitched two no-hitters in his freshman year.

Conditions at the Parade Ground worsened during the years leading up to the 2004 renovation. Franco remembered playing there as a youth with mixed emotions. “I have a lot of fond memories of the place,” he said, “but to be honest, the conditions weren’t that great.”35

In two minor league seasons, Franco pitched for San Antonio, Albuquerque, and Vero Beach before being traded to the Cincinnati Reds in May 1983. Transitioned from a starting role to the bullpen while in the minors, Franco never started a game in the major leagues. Called up to the Reds in ’84 he pitched in relief until traded to the Mets in 1990. He spent 14 seasons in a Mets uniform.

Franco missed the entire 2002 season after undergoing Tommy John surgery, but he recovered and returned in May 2003. Franco was not a hard thrower. His outpitch was a circle change. It had a screwball effect, spinning away from a right-handed hitter and running in on lefties. He signed a one-year deal with the Houston Astros for 2005 making him, at the age of 44, the oldest active pitcher in the major leagues. Released in July, Franco retired from baseball. Franco was inducted into the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame.

At his peak, Franco reigned as an elite closer. He was a four-time All-Star, the NL Rolaids Relief Man of the Year on two occasions, and in 2001 was the recipient of the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award. He played in the postseason in 1999 and the World Series in 2000. His postseason record is 2–0, with one save, and 1.88 ERA in 15 appearances. John served as the team captain of the Mets from 2001–04. The 5-foot-10 left-hander finished his career with 424 saves, fourth all time and the most by a lefty. If number of saves becomes an important stat to Hall of Fame voters, then John Franco, along with Joe Torre, may well eventually add to the Parade Ground roster of Hall of Famers in Cooperstown.

The Parade Ground was a field not only of unfulfilled dreams, but of realized ones as well. At least 50 World Series rings are worn by players whose early careers were to some degree nurtured there. Can any other amateur venue in the nation rival that?

But why Brooklyn? Why the Parade Ground? Population plays a role: Brooklyn currently has 2.6 million inhabitants. The Ground is a large facility, having 13 diamonds during the bulk of its history, with as many as 60 or more games being played on Saturdays and Sundays in its heyday. This schedule and the quality of the competition attracted players from all over the borough, concentrating the best the borough has to offer. Managers and coaches with the knowledge of the game and the wherewithal to instruct a willing bunch of dreamers were attracted to the fertile ground, as well.

The Parade Ground, Brooklyn’s Elysian Fields, has been a place where dreams come true. But that sense of pride, of maturation, of discovery, and of memory is not confined to the greatest of the gems of the Parade Ground who made it to the major leagues. It is embodied with as much sanctity in the ones who simply were not good enough. Alton R. Waldon, later a congressman and a judge, recalled with reverence, “I once hit a home run at the Parade Grounds; I touched heaven with that wallop.”36

ANDREW PAUL MELE was born and raised in Brooklyn and retired from working at the Brooklyn Public Library in 2003. He played baseball at the Parade Ground from the late forties to the mid-sixties and is the author of “The Boys of Brooklyn: The Parade Ground, Brooklyn’s Field of Dreams.” He is currently active as a baseball player with a group of septugenarians called the Old Boys of Summer, as seen in The New York Times.

Notes

1. Webster’s College Dictionary (New York: Random House, 2001).

2. Pete Palmer and Gary Gillette, eds., ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Sterling Publishing, 2005).

3. Curt Smith, Voices Of Summer (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005).

4. Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes To Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1974).

5. Thomas Barthel, Baseball’s Peerless Semipros (Harworth, NJ: St. Johann Press, 2009).

6. Ibid.

7. Ted Schrieber, personal interview, November 2011.

8. Richard Goldstein, Superstars and Screwballs (New York: Plume, 1992).

9. Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax, A Lefty’s Legacy (New York: HarperPerennial, 2003).

10. Ronald A. Mayer, The 1937 Newark Bears (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994).

11. Larry Yaffa, telephone interview, March 2008.

12. Larry DiVita, personal interview, October 2007.

13. Leavy , op. cit.

14. John Chino, telephone interview, October 2007.

15. Leavy , op. cit.

16. Tommy Davis, telephone interview, January 2008.

17. Ibid.

18. Fred Wilpon, telephone interview, January 2008.

19. Leavy , op. cit.

20. Fred Weber, personal interview, October 2007.

21. Leavy , op. cit.

22. Frank Chiarello, personal interview, May 2012.

23. Leavy , op. cit.

24. Rico Petrocelli and Chaz Scoggins, Tales from the Impossible Dream Red Sox (Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing LLC., 2007).

25. Larry Anderson, personal interview, March 2008.

26. Jim McElroy, personal interview, October 2007.

27. Joe Torre with Tom Verducci, Chasing the Dream (New York: Bantam Books, 1997).

28. Jim McElroy, personal interview, October 2007.

29. Ken Avalone, personal interview, October, 2007.

30. Jim McElroy, personal interview, October 2007.

31. Vincent Lorenzo, personal interview, September 2007.

32. Ricky Tepedino, personal interview, March 2012.

33. Andrew Paul Mele, The Boys of Brooklyn (Bloomington, IN: Author House, 2008).

34. Dan Liotta, personal interview, September 2007.

35. Fred Weber, personal interview, October 2007.

36. Mele, op. cit.