The Final Flight of Tom Gastall

This article was written by Cort Vitty

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

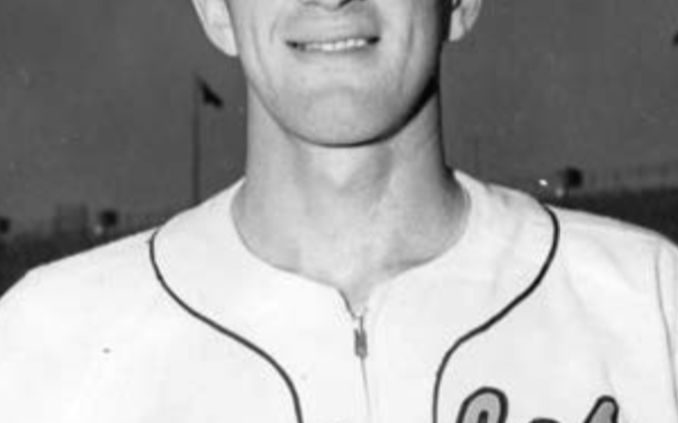

The 1955 crop of baseball “bonus babies” included Massachusetts native Tom Gastall, born on June 13, 1932, in Fall River, to Thomas and Concetta Gastall. (A “bonus baby” rule was first implemented by the major leagues in 1947, intended to restrict the inflated offers made by wealthy club owners seeking to monopolize the best young talent.1 Stipulated in the rule implemented in 1953 was the requirement that prospects signing a contract exceeding $4,000 remain on the major-league roster, rather than honing their skills at the minor-league level, for two years.) Young Tom developed into an exceptional all-around athlete while attending Durfee High School in Fall River, class of 1951.

The 1955 crop of baseball “bonus babies” included Massachusetts native Tom Gastall, born on June 13, 1932, in Fall River, to Thomas and Concetta Gastall. (A “bonus baby” rule was first implemented by the major leagues in 1947, intended to restrict the inflated offers made by wealthy club owners seeking to monopolize the best young talent.1 Stipulated in the rule implemented in 1953 was the requirement that prospects signing a contract exceeding $4,000 remain on the major-league roster, rather than honing their skills at the minor-league level, for two years.) Young Tom developed into an exceptional all-around athlete while attending Durfee High School in Fall River, class of 1951.

Tom next attended Boston University, where the 6-foot-2, 187-pounder was a multisport star, including starting at quarterback on the football team. In a grim coincidence, Gastall took over signal-calling duties following the graduation of Harry Agganis, who, like Gastall, was a prized baseball prospect who would meet an early end.2

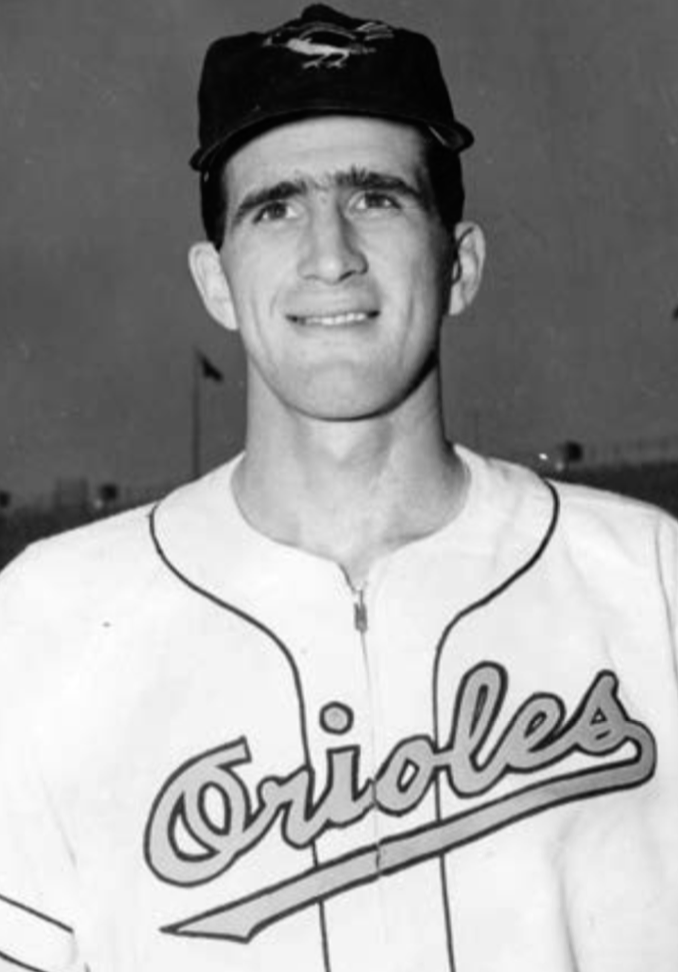

Despite the potential of a promising gridiron career, Gastall chose to sign a baseball contract following graduation. At the time, he was considered “the finest catching prospect since Mickey Cochrane in the greater Boston Area.”3 The Baltimore Orioles ownership group exhibited a firm commitment toward improving the performance of the club by signing Gastall to a $40,000 contract.

The right-handed hitter reported to Orioles spring training in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1955. Gastall immediately struck teammates as a nice, kind-hearted guy. This view apparently stemmed from an incident early in spring training. Gastall found a stray dog wandering around the team’s training facility—or the pooch located Tom. Gastall and the pup became inseparable; his new canine companion followed him everywhere. The tuckered-out pup routinely napped in the pocket of Tom’s catcher’s mitt.4

During the 1955 season, Gastall saw action in 20 major-league games. He essentially served as the team’s fourth-string catcher, slotted behind Hal Smith, All-Star veteran Gus Triandos and the competent Les Moss. Facing big-league pitching, Gastall recorded three singles and a double in 27 at-bats, compiling a batting mark of .148/.233/.185.

Gastall used $2,000 of his bonus money to become the proud owner of a second-hand Ercoupe small aircraft. He housed the plane at Harbor Field, a small airport just east of Baltimore City. Soon after Gastall made the purchase, a fellow pilot recognized the plane as an aircraft previously involved in an accident.5

In the 1955–56 offseason, Gastall devoted a good deal of his time to taking practice flights; his student license qualified him to fly solo only in a small aircraft. Gastall diligently worked toward logging sufficient flying hours to become a full-fledged pilot.

On September 19, 1956, the Orioles returned home from a road trip and manager Paul Richards announced that there would be a workout the next day, an open date on the schedule. The day dawned bright and sunny, but gusty winds began swirling around the field at noontime. The rapidly changing weather conditions prompted Richards to cancel the afternoon practice.

Suddenly presented with an unexpected free afternoon, Gastall considered taking a flight and logging some flying hours. Gastall had feared that Richards might try to stop him from flying, but numerous teammates knew of his hobby. Upon hearing Gastall’s plan for the afternoon, teammate Willy Miranda minced no words: “The wind will blow that bucket of bolts all over the place.”6 Gastall shrugged and issued his standard reply to such comments, saying that flying was safer than driving.7 Gastall’s mentor and friend, first-string catcher Triandos, also attempted to dissuade him from flying.

Gastall arrived at Harbor Field at around 4:50 pm to prepare for takeoff. About 90 minutes into the flight, he issued a distress message via radio: “I’m going down into the water.”8 It was his only transmission.

A rescue force of 21 planes and nine boats was quickly deployed. Despite this intensive effort, no remains were recovered.

The next night, as teammates prepared for Baltimore’s game against the Washington Nationals, the clubhouse went silent following an announcement about Gastall’s crash. The Orioles gathered around his locker, devoting a moment of silent prayer in acknowledgement of his apparent passing. Uniform number 10 was still hanging next to his catcher’s gear.

During the search, a set of seat cushions washed ashore near Riviera Beach, and Tom’s wife, Rosemary, was contacted at the couple’s home. She arrived on the scene to examine the debris and sadly verified the gear as belonging to Tom.9

Finally, on the morning of September 25, a body washed ashore onto Riviera Beach. A personalized Boston University ring bearing the inscription “TEG 1955” confirmed it as Tom Gastall’s body. Upon hearing the news, road roommate Billy Gardner said, “It’s the saddest story there is, a good guy dying like that with his whole life ahead of him.”10

Tom Gastall saw action in 52 games over two major-league seasons, with 15 hits in 83 at-bats; he registered six bases-on-balls while striking out 13 times. His lifetime batting average was .181, with an on-base average of .242 and a slugging average of .217. He was only 24 when he died. There’s no telling what the future may have brought.

Funeral services were held on September 29, 1956, at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in Fall River. Survivors included Rosemary and their 15-month-old son.

In his Baltimore Sun column, sports editor Bob Maisel wrote: “The home runs and no-hit games eventually fade, but the sight of other players casting sidelong glances at a locker they knew would never be used again is something that can’t be forgotten.”11

A SABR member since 1999, CORT VITTY grew up in New Jersey and has been a fan of the New York Yankees since 1959, subsequently making numerous trips Yankee Stadium. Articles authored by Vitty are posted on the SABR website and included in numerous SABR publications. Vitty and his wife Mary Anne reside in Maryland, with Sparkle, their affable goldendoodle.

Notes

1 Paul Dickson, The Baseball Dictionary, Third Edition (New York: Norton & Company, 2011), 125.

2 Agganis was a first baseman who turned down a big contract from the Cleveland Browns to sign with the Boston Red Sox, for whom he played in 1954 and ’55. He died of a pulmonary embolism at the age of 26 on June 27, 1955. Mark Brown and Mark Armour, “Harry Agganis,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/69d56ecd.

3 “Tom Gastall, Orioles Player; Missing After Flight Over Harbor,” Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1956.

4 Bob Maisel, “Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, January 15, 1961.

5 Maisel.

6 Maisel.

7 Maisel.

8 Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1956.

9 “Tom Gastall’s Body Found at Riviera Beach,” Baltimore Sun, September 26, 1956.

10 Bob Maisel, “Gloom Fills Bird Players,” Baltimore Sun, September 23, 1956.

11 Maisel.