The Flight of the Seattle Pilots

This article was written by Bill Mullins

This article was published in Time For Expansion Baseball (2018)

Seattle Pilots spring training program from 1970. The franchise began spring training as the Pilots but officially became the Milwaukee Brewers on April 1 (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

Despite a nucleus of enthusiastic fans, overall passion for baseball in Seattle in the late 1960s was lukewarm at best. Between 1919 and 1968, attendance for the minor-league Rainiers, and later the Seattle Angels, had been steady, even robust. The Pacific Coast League team led the circuit in ticket sales for several years after World War II, but by the 1960s, attendance was slumping.2 Several local entrepreneurs, such as Dewey Soriano and his brother Max, were eager to bring major-league baseball to Seattle.

Chief among these boosters was Joe Gandy, a local Ford dealer, who was indefatigable in his efforts to build a ballpark to attract a team. And, of course, the entire contingent of sportswriters at the two local daily newspapers, the Post-Intelligencer and the Times, beat the drum enthusiastically.

In an era when one might speak of “City Fathers,” there were civic leaders, usually not politicians, who set the course for the city behind the scenes. Ed Carlson, the president of Western International Hotels, was one of them. Carlson provided the impetus for the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962. Attorney James Ellis was another municipal visionary. He worked to prepare Seattle for growth, cleaning up the polluted Lake Washington to the east of the city, while successfully urging citizens to modernize infrastructure for future economic development. His multifaceted Forward Thrust election campaign to approve construction bonds included a domed stadium.

These men smiled upon the idea of big-league sports in their city, but, unlike the boosters, did little in the beginning to facilitate a team. It was not until Seattle battled to preserve major-league baseball for their city that the civic leaders took a real interest in the Pilots.

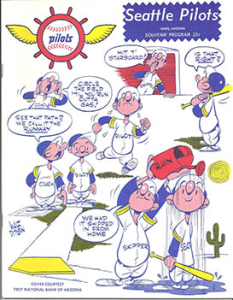

Opening Day at Sicks Stadium, April 11, 1969 (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

The third group of decision-makers in the city was the politicians; some were uninterested in sports while others incorporated campaign promises to build a stadium. Mayor James D’Orma “Dorm” Braman was of the former group. He and his successor, Floyd Miller, had little interest in advancing sports in the city and no desire to finance a playing venue. At the other end of the spectrum sat John Spellman, the King County executive (something like the mayor of Seattle’s home county) and County Commissioner turned Councilman John O’Brien. O’Brien had been a star basketball player at Seattle University and an infielder and pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates, while his twin brother, Eddie O’Brien, became the bullpen coach for the Pilots. With his pedigree, John O’Brien could also be included in the circle of boosters.

Today there is serious debate about who bears responsibility to build a ballpark in order to lure a new team or perpetuate an established club. Historians of sports business have argued that construction is surely a losing economic proposition for the local government. In the mid- to late twentieth century the economics might have been debated, but a city without a new venue would be a city without a franchise.3

The attempts undertaken by the City of Seattle and King County to build a major-league ballpark followed an exceptionally bumpy road. The first effort was clearly premature. As early as 1957, Dewey Soriano suggested that a stadium with a plastic dome could serve as a multisport and convention building in order to circumvent Seattle’s rainy climate. In 1960, stimulated by support from Washington Governor Albert Rosellini, the city and county hired Stanford Research Institute to conduct an economic study of the region and the feasibility of building a stadium. SRI concluded that a stadium could be built for $15 million; baseball would almost surely plant a franchise in the Northwest to furnish nearby playmates for the Giants and Dodgers.4 Stadium bonds were placed on the November 1960 ballot. A tepid campaign consisting of fliers and bumper stickers was launched and encouraged by the local media. A 60 percent supermajority was required. The campaign garnered less than 48 percent of the vote.5

After the surprise success of the Century 21 Exposition (Seattle World’s Fair), the boosters were ready to attempt another public stadium campaign. Joe Gandy had assumed the leadership of the Fair from Ed Carlson midway through the project and brought it to fruition. He later proclaimed, “The Fair was a dying dog. And a lot of people thought I’d be the one to bury it.”6 His next project oversaw the construction of a ballpark to lure a team. The vote, originally scheduled for 1964, was delayed until 1966. In the meantime, something stoked the boosters’ fire. Gabe Paul and William Daley, owners of the Cleveland Indians, examined Seattle as a possible target to move their team. Mayor Braman met with the two and effectively dissuaded them from coming to Seattle. When Paul asked Braman when Seattle would be ready for major-league baseball, the mayor responded, “Oh, in about five years.” The mayor’s assistant helpfully added, “Seattle is not panting with excitement, mind you, but is in favor of [a franchise].”7 To be fair, Braman’s lack of optimism was not misplaced. A ticket sale to lure the Indians fell well short; and Seattle did not boast a truly established team until the Mariners years later. The Indians remained in Cleveland.

Nonetheless, Gandy and his crew persevered. When the National Football League deliberated expansion in 1966, it dropped broad hints that Seattle would be considered with an appropriate stadium. The drive for stadium bonds gained momentum. This time, the venue in question would be a $38 million domed stadium. Gandy went into overdrive. An array of civic leaders enthusiastically endorsed the bond issue.8 The sportswriters spilled gallons of ink in support.9 Even Braman agreed to follow the will of the public.10 In a televised debate, when two of Gandy’s opponents questioned why the public had to finance the stadium for a private ownership, his response was unconvincing. Consequently, the wind seemed to blow out of the sails.11 The voters endorsed the bonds by 52.5 percent – but 60 percent was required.12 Once again the stadium and the possibility of an NFL franchise and a major-league baseball team went a-glimmering.

Charlie Finley accomplished what Joe Gandy, the other boosters, and the sportswriters failed to do: He won a baseball franchise for Seattle, and made possible a domed stadium in the city. Finley did not do this wittingly, but he turned out to be the essential catalyst for Seattle’s entrance into the major leagues. The owner of the Kansas City A’s was certainly aware of Seattle. Finley had visited the city in 1967 with an eye to moving his team to the Puget Sound region. He and Mayor Braman had more encouraging conversations than were held with the Cleveland ownership, but any agreement foundered on the terms of use for the city’s minor-league field, Sicks’ Stadium, and Finley’s freedom to move if the third time of approving stadium bonds was not the charm.

Finley’s dalliance with Seattle may have been a ploy to leverage the best deal he could from Oakland. In any case, Finley moved his team to the Bay Area in 1968, leaving Missouri Senator Stuart Symington furious. Symington, like any US senator spurned, attacked baseball’s Achilles heel, its antitrust exemption. Not only did he demand a replacement team but he demanded that it begin play in 1969 rather than 1971. Those were two years of preparation lost to Pilots ownership. The American League quickly complied, approving an expansion team for Kansas City. And the AL decided to beat the National League to the unoccupied Pacific Northwest by granting Seattle a team.13

The boosters who attended the American League meeting were not caught unprepared. They presented a film of the Great Northwest and then detailed the economic strength of the region. But to even the most optimistic Seattleites, winning a franchise at the October 1967 League meeting was a surprise, and the city had done little to earn it.

Seattle Pilots president Dewey Soriano and general manager Marvin Milkes (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

Ownership was not contested. Shortly before the meeting, American League President Joe Cronin contacted Dewey Soriano to form a partnership in case Finley’s demands toppled the dominoes toward Seattle.

Soriano was a baseball insider and a logical choice. Born in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, he grew up in Seattle constantly involved with local baseball. He had served as general manager of the Rainiers and had risen to the presidency of the Pacific Coast League when Cronin called. Soriano assured Cronin that he could form a local ownership syndicate.14 The promise did not hold. Though Dewey and brother Max, PCL counsel, were the local face of the team, they held only 33 percent of the franchise shares. The primary owner was William Daley, with 47 percent of the stock.15

The former Indians owner must have been impressed with Seattle’s potential when he visited in 1964. He proclaimed, that he “would enjoy the opportunity of getting in bed” with the Sorianos.16 The consortium became known as Pacific Northwest Sports, Incorporated. Daley verbally guaranteed the $8 million that the league required to capitalize the team, but only in the event of a cash shortage.17 In the meantime, the Bank of California issued a $4 million loan. In May 1969, two months into the season, concessionaire Sportservice provided an additional $2 million loan in return for a 20-year “follow the team” contract.18 That meant Sportservice was the team’s concessionaire no matter where it played.

As the American League approved the new owners, Jerold Hoffberger of the Orioles fretted, “We are actually convinced there is no other group in Seattle, they have been scared off for some reason.” Later he regretted not having examined the ownership more carefully.19 The leveraged arrangement and Daley’s $8 million promise loomed large in the ultimate fate of Seattle’s new baseball team.

Staffing a front office, assembling a team, assuring an adequate temporary place to play, and building a permanent domed stadium were pressing priorities for Dewey Soriano. The most important front-office hire was general manager Marvin Milkes. Milkes started in the Cardinals organization and won his credentials with the Los Angeles/California Angels. To say he was intense is an understatement. As he described himself, “I’m very candid. I get a little impatient sometimes and I don’t smile all the time when we lose. … This is not a buddy-buddy organization. I believe in results.”20 Sportswriter Hy Zimmerman observed, “[Milkes] has splendid mental furniture, but it may need re-arranging.”21 The intense will to win while overseeing an expansion team resulted in 53 different players on its 25-man roster.22

The front office consisted of a capable collection of professionals who were knowledgeable about the local market along with experienced baseball hands. Bill Sears, erstwhile public-relations director for the Rainiers, held the same role for the Pilots. Harry McCarthy came from the San Francisco Giants as ticket manager. Ray Swallow and Art Parrack, both from the A’s, headed scouting and the farm system, respectively. Harold Parrott, longtime Dodgers official, and most recently with the Angels, was hired at twice his Dodgers salary to oversee promotions and sales. He was gone by the first of June, a cost-cutting casualty, and an indication of apprehension over cash flow.

A press conference held in Berkeley, California to discuss efforts to keep the Pilots in Seattle, January 27, 1970. From left: John Spellman, Dan Evans, Eddie Carlson, Wes Uhlman, Slade Gorton, and Fred Danz (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

Bringing together a team also signaled some early financial concerns. The team purchased the contracts of outfielder Mike Hegan and pitcher Jim Bouton from the Yankees in June 1968, almost a year before the team’s debut. (Bouton, of course, became famous as the chronicler of the Pilots’ one and only season with his tell-all book Ball Four.) The expansion draft occurred in October 1968. Initially, the Pilots decided to build for the future, selecting promising players left unprotected from the draft. The day before the draft, Dewey Soriano had a change of heart. Season-ticket sales, which had been running for two or three months, were lagging. A member of the front office told the New York Times, “We felt we needed a product someone could understand right now.”23 So it would be veterans, not emerging major leaguers. Many had been stars, but now were aging, injured, or both. Don Mincher, drafted from the Angels, was beaned in 1968; Tommy Davis (White Sox) never fully recovered from a broken ankle in 1965; Rich Rollins (Twins) had sore knees; Steve Barber (Yankees), a sore arm. Tommy Harper from the Indians was probably the best draftee. As a Pilot, he led the American League with 73 stolen bases. Others were typical expansion picks: Ray Oyler (Detroit) hit under .200, Marty Pattin (Angels) had his moments, but finished 7-12, and catcher Jerry McNertney (White Sox) was steady but unspectacular. Milkes hired Joe Schultz, St. Louis third-base coach, to manage the team. The easygoing, affable Schultz was a good buffer between the players and the hard-driving Milkes. The former catcher was a baseball man, but ill at ease with reporters. “He was as rough as his gnarled fingers,” his press liaison remembered.24 Schultz was able to select one of his coaches, conditioning coach Ron Plaza. Pitching coach Sal Maglie and third-base coach Frankie Crosetti were probably chosen for name recognition.

The Pilots’ publicity crew devised several engaging ideas. There was a name-the-team contest. Few were surprised that Dewey Soriano, part-time harbor pilot, declared that Pilots was the winning name. The logo was both nautical and aeronautical, featuring a ship’s wheel around a baseball, with wings attached. A catchy song was written for the team: “Go, Go, You Pilots.” The uniforms sported a cap with a naval officer’s “scrambled eggs” on the bill. The radio deal was probably the Pilots’ greatest business accomplishment. The team signed a deal with Golden West Broadcasting for $850,000 a year. The network ranged from Alaska to North Dakota and south to Elko, Nevada. (This hinterland proved to be more supportive of baseball in the Northwest than the locals. Numerous families planned their vacations to Seattle when the Pilots were at home.) Jimmy Dudley, whose soft Southern drawl was reminiscent of Red Barber, came from Cleveland to anchor the broadcasts.25 A TV contract never materialized. Soriano reportedly asked for $20,000 per game, then lowered it to $10,000, but could not strike a deal.26

But the crucial negative decision involved ticket prices. Soriano believed that a new major-league market would pay for the privilege to watch the team; prices ranged from $6 box seats to $2.50 for backless bleacher seats. Only the San Francisco Giants sold tickets priced that high; and a number of clubs charged as little as 75 cents.27 The reaction was immediate. The Seattle Times sports editor exclaimed in print, “Great Soriano! Where are the cheap seats?”28

Season-ticket sales lagged from the beginning. At the end of the 1969 season, Pilots attendance stood fifth lowest among major-league clubs at 677,944, some 150,000 below break-even.29 Could layoffs at Boeing have restrained fan enthusiasm? It’s possible. The Boeing recession that crested in 1971 was just getting started in 1969. Unemployment in Seattle was steady at 3.6 percent in the Pilots’ only season, but some Boeing families might have decided that a brace of high-priced baseball tickets was not the wisest choice in the shadow of increasing layoffs at the city’s largest employer.30 But premium prices for expansion baseball were a more likely culprit.

The quality of play outpaced expectations for over half the season. Although they were 16 games under .500, the Pilots were in third place among six teams in the American League West by the end of July. Then age and ability began to show. Injuries and losses multiplied. At the end of the 1969 season the record was 64 wins and 98 losses. That landed them in last place in the division. Only Cleveland suffered more losses in the American League.

If there was a worse plague than a lagging box office for the Pilots, it was a ramshackle playing field. They were scheduled to play in an upgraded minor-league ballpark, Sicks’ Stadium, for four years, then move into a new domed stadium. The American League granted Seattle a franchise on the condition that voters approve the King County Multipurpose Domed Stadium. The ballot to ratify stadium construction bonds passed with 62 percent in a February 1968 election.31 The success of that vote was the good news.

Virtually all of the other stadium stories were bad news. Sicks’ was a model minor-league park when it opened in 1938, but work was required to bring the city-owned facility up to the undefined major-league standards. Negotiations to use the ballpark continued until the early fall of 1968. The city was determined for rental fees to pay for all remodeling costs. Braman was all but immune to any threats to withdraw the franchise. The final agreement settled for a five-year lease at $165,000 per year, though the Pilots fully expected to move to a new building in four. The city promised $1.75 million to refurbish Sicks’ and expand it to 28,000 seats.32

The timing of the September 1968 agreement left seven rainy months to remodel the stadium. Initial bids came in 65 percent over budget.33 Corners were cut and seating scaled down to 25,000. The ballpark never reached major-league quality, according to Charlie Berry (Joe Cronin’s man in the field), Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, and several American League owners who visited Sicks’.34 Fans filing into the gates on Opening Day, April 11, could hear hammers ringing as workmen continued to install seats. Post-Intelligencer sportswriter John Owen captured it best, commenting, “Not bad for a bunch of brash amateurs. Even if they did get caught with a few of their bleachers down.”35 An estimated 19,000 seats were completed by Opening Day and capacity probably never reached 25,000.

Problems with Sicks’ vexed the Pilots ownership throughout the season. The sound system failed, the bench seats warped, and a short circuit in an electrical vault almost burned down the ballpark. Worst of all, there was no water pressure in the ballpark after the seventh inning if attendance rose above the season’s average level of 8,370.36 Soriano complained to the press about these shortcomings, hardly an ideal strategy to advertise his product to a less than passionate fan base. Pacific Northwest Sports then withheld a promised surety bond, demanding repairs and upgrades. In March 1969, Floyd Miller replaced Braman as mayor and was no more enamored of baseball than his predecessor. By August 1969 Miller threatened to evict the Pilots. Daley and Cronin came to Seattle and smoothed things over.

The great hope amid this wrangling was the promise of the brand-new domed stadium. After the successful ballot initiative in February 1968, things bogged down. A squabble over the ballpark’s location erupted. The Stadium Commission’s consulting firm recommended a spot at the southern edge of Seattle. Meanwhile, civic leaders lobbied hard for Seattle Center, the site of the World’s Fair. Though closer to downtown, it was a more expensive location. When the commission bowed to the downtown pressure, a successful petition was circulated for an initiative vote. In January 1970 voters rejected the Seattle Center site. A new Stadium Commission would have to start all over. Pacific Northwest Sports understood the ramifications of the siting controversy: The ballpark might not be under construction by the December 1970 deadline imposed by the American League.

The situation in Seattle had become bleak. The region was not excited about the team. The current ballpark was inadequate. Relations with the city were strained at best. Moving to the new venue was becoming a steadily more distant prospect. Daley made his displeasure known. “We don’t seem to be getting support from the Seattle business people,” he groused at the end of August 1969, “If I continue to get the brush-off I’m going to lose interest too.”37 Hy Zimmerman, rebutted in a Seattle Times column entitled “Won’t You Go Home Bill Daley?”38 This may not have been the final straw. However, by early September, Pacific Northwest Sports had begun to negotiate with the Milwaukee Brewers, a civic group led by Allan H. “Bud” Selig, to move the Pilots to Wisconsin.39 Unlike Daley’s group, Selig’s partners were well-heeled. Firms such as Schlitz, Evinrude, Northwest Mutual Life, and Oscar Meyer were represented. Also, they had Milwaukee County Stadium, and it was in good shape.40 A deal was struck at the 1969 World Series in Baltimore to sell the Pilots to the Milwaukee consortium, and it quickly became an open secret in Seattle. Although that is what ultimately happened, the Pilots had not yet become the Brewers.

Persuaded by obvious comments about baseball’s antitrust exemption from Washington’s two U.S. senators, Warren Magnuson and Henry Jackson, Cronin gave Seattle about a month to devise a competing offer for the Pilots. Ed Carlson spearheaded the effort, mainly to preserve Seattle’s esteem. Fred Danz, a local theater owner, was the face of the undertaking. Carlson appealed to his fellow city fathers’ sense of civic pride and rounded up a bevy of Seattleites to pledge $100,000 or more. Daley would become a 25 percent owner and the Sorianos, at Cronin’s insistence, would be cashed out. The goal was to add $4.8 million to the $4 million Bank of California loan and the $2 million advanced by Sportservice to cover the purchase price and furnish operating capital of $1.7 million.41 On November 18, 1969 the Post-Intelligencer’s front page proclaimed, “It’s the SEATTLE Pilots.”42 But a month later, Danz announced, “I felt I should tell the public there is trouble in Paradise.” The Bank of California had informed the Sorianos in September that if the team was transferred, its loan would be due and payable.43 After a futile appeal to Seattle banks for loans to replace the Bank of California financing and an unsuccessful ticket drive, the Danz initiative was done.

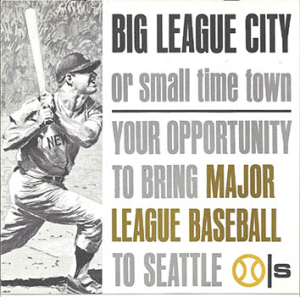

The front cover of a 1965 brochure by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce urging fans to support the Seattle Rainiers to demonstrate that Seattle is committed to support a major league team (Courtesy of David S. Eskenazi)

Now Ed Carlson openly took up the reins. The Pilots would become a publicly held nonprofit organization. Here was civic leadership at its purest. Hundreds of community leaders invested what they could afford to keep the team and keep egg off the public face of Seattle. Any profits that were not reinvested into the organization would go to city charities and amateur sports.44 When Carlson issued his proposal at the American League meeting that was supposed to approve the Danz ownership, the owners were dumbfounded. Cronin observed, “I think we are dealing with a different breed of cat.”45 Some owners saw it as a threat, fearing they would have to follow suit and distribute their profits to their communities. The American League owners gave Carlson permission to try to create a viable ownership team, but privately expected – hoped – he would fail. Behind closed doors the Orioles’ Frank Cashen commented, “By going along with them, all we are doing is giving them enough rope to hang themselves because they just can’t make it.”46

The next meeting was in 15 days, in early February 1970. More than 60 businesses, labor organizations, and individuals agreed to assist Carlson. He persuaded Bank of California and Sportservice to perpetuate their loans and for Daley to remain a partner. When Carlson and his allies met in Chicago on February 6, everything was in place (although it is questionable whether the prospective ownership team was sufficiently capitalized). The American League owners were nervous about the funding, but could not accept the nonprofit. They wondered who would be in charge of a public-ownership syndicate. After questioning Carlson, the owners tried to make a decision. Cronin announced to the press that “We took nine million votes.” (Actually, it was nine.) The Carlson plan fell one vote short.47 The owners then voted to keep the Pilots in Seattle, retain Pacific Northwest Sports Incorporated as owners, and lend them $650,000.48 The American League understood that moving the team would awaken the wrath of two powerful senators. Consequently, the league scrambled to find a buyer to save the team. Bowie Kuhn even sounded out Carlson to see if he would try again. The answer was a firm “No.”49 The league owners’ decision proved to be no more than a liferaft. The Seattle press was incredulous.

Wisely, the Sorianos stepped aside from active participation to leave Roy Hamey and Marvin Milkes to run the team. There was some shuffling. Dave Bristol and a new group of coaches replaced Joe Schultz. Milkes, as was his wont, traded several players, including Don Mincher, mainstay pitcher Diego Segui, and fan favorite Ray Oyler. There was some attempted civic fence-mending, but ticket sales were slipping.

The team was collapsing financially and the league, fearful of having baseball’s antitrust exemption questioned, had no remedies. The state of Washington let Cronin know it would file an $82.5 million lawsuit for breach of promise, financial damage, and fraud if the team moved, and had obtained a court restraining order against relocation.50 Pacific Northwest Sports Incorporated was not going to continue in Seattle and the only solution was to declare bankruptcy. Everyone knew that if the declaration was approved, the sale to the Milwaukee group would be the bankruptcy court’s remedy.

The deal to sell the team to the Milwaukee Brewers group became official on March 8, 1970. All that was lacking was American League approval. The last days of the Pilots were spent in court. In the morning, there were hearings in King County Superior Court over the restraining order. In the afternoon, the federal bankruptcy court heard arguments. Pacific Northwest Sports asserted that it had lost $2.3 million in 1969 and was unable to pay its debts. The accounting firm Peat Marwick later estimated losses at about $630,000. Most importantly, Pacific Northwest Sports could not repay its loans from Bank of California and Sportservice. Moreover, if player salaries were deferred by 10 days, the players would become free agents.51 Not mentioned was Daley’s crucial written promise of $5 million to $8 million in the event of insolvency.52 In addition, bankruptcy judge Sidney Volinn overlooked the clause that the American League by its own constitution was responsible for the club if it became insolvent.53

With the regular season just days away, the $10 million deal offered by the Milwaukee syndicate was too attractive a solution to ignore. Volinn declared Pacific Northwest Sports Incorporated bankrupt. The injunction against moving the team to Milwaukee had already been stayed. On April 2, 1970, the formal papers were signed.54 With “Brewers” newly stitched on their uniform tops, the team opened the season in Milwaukee County Stadium against the California Angels on April 7.

Volinn’s ruling protected Pacific Northwest Sports from any lawsuits. But since the American League was liable, the State of Washington sued the circuit. After six years of litigation, the league settled out of court in January 1976, granting Seattle a new franchise that would become the Mariners.

The Seattle Pilots story is one of more errors than hits. The American League was eager to stake out a new territory. The AL owners’ enthusiasm probably outpaced that of most Seattleites. Attendance was not the worst in the league, but it fell short of reasonable expectations. Charging the highest prices in the league did little to kindle enthusiasm among the fans. Ownership, including those who scrambled to save the team at the last minute, was undercapitalized. William Daley is the only figure who could have afforded to absorb even moderate losses and he reneged on his $8 million pledge to shore up the franchise. The ballpark situations – both Sicks’ and the squabbles over the new domed stadium – burdened an already struggling franchise. For the boosters it was a bittersweet experience. For the civic leaders the Pilots brought more embarrassment than pride. And for most of the politicians the whole situation was an annoying distraction. In short, Seattle was not ready in 1969 for a major-league team. Groundbreaking on the Kingdome did not take place until December 1972, nearly three years after the Pilots departed Seattle for greener pastures in Milwaukee.

BILL MULLINS is a 10-year SABR member. He received his Ph.D. in history from the University of Washington and is professor of history emeritus at Oklahoma Baptist University. This article is derived from his book Becoming Big League: Seattle, the Pilots, and Stadium Politics published by University of Washington Press in 2013.

Notes

1 Rockne quoted in Nick Russo, “An Exhilarating Big League Bust: The Seattle Pilots,” in Mark Armour, ed., Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2006), 121.

2 Carson van Lindt, The Seattle Pilots Story (New York: Marabou Publishing, 1993), 26.

3 See Rodney Fort, Sports Economics (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 2003), 300-301 and Michael Danielson, Home Team: Professional Sports and the American Metropolis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 225.

4 Seattle Times, September 13, 1960 and Eric Duckstad and Bruce Waybur, Feasibility of a Major League Sports Stadium for King County, Washington (Menlo Park: Stanford Research Institute, 1960), 59.

5 Folder 1, box 4, Series 261 Bond Files, Record Group 102 Commissioners, King County, Washington Archives.

6 Gandy quoted in Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 5, 1966.

7 Paul, Braman, and Devine quoted in Sam Angelhoff, “Are We Ready for the Big Leagues?” Seattle: the Pacific Northwest Magazine, January 1965, 10, 14-15.

8 See Seattle Post-Intelligencer, September 20, 1966; Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 31, 1966; Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 24, 1966; and Seattle Times, September 14, 1966.

9 For example, see Georg Meyers in the Seattle Times, May 11, 1966.

10 Braman quoted in Seattle Post-Intelligencer, September 7, 1966.

11 Folder 18, box 20 and folder 3, box 22, Gandy Collection, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

12 Folder 10, box 8, Series 261 Bond Files, Record Group 102 Commissioners Washington State Archives Puget Sound Branch, Bellevue, Washington.

13 Plaintiffs’ Brief Opposing New Motion from Washington v. American League, folder 9, box 5, Seattle Municipal Archives, City of Seattle Law Department Baseball Litigation Files.

14 Max Soriano, interview by Mike Fuller, January 1994, http://www.seattlepilots.com/msoriano_int.html and Tacoma News Tribune, October 31, 1967.

15 Max Soriano, interview by Mike Fuller, January 1994, http://www.seattlepilots.com/msoriano_int.html.

16 Daley quoted in deposition of Charles Finley, folder 5, box 3 Washington v. American League, Washington State Archives, Northwest Branch, Bellingham, Washington.

17 Folder 26, box D-1, Series 491 Director’s Files, Record Group 502 Stadium Administration, King County Washington Archives.

18 Affidavit of William Daley, folder 1, box 6, Seattle Municipal Archives, City of Seattle Law Department Baseball Litigation Files.

19 Hoffberger in transcript of American League meeting, December 1967 in deposition of Charles Finley, folder 5, box 3 Washington v. American League, Washington State Archives, Northwest Branch, Bellingham.

20 Milkes quoted in Milwaukee Journal, April 5, 1970.

21 Seattle Times, December 20, 1970.

22 Nick Russo, “An Exhilarating Big League Bust: The Seattle Pilots,” in Mark Armour, ed., Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest, 117.

23 New York Times, April 13, 1969.

24 Author’s interview with Rod Belcher, January 8, 2008.

25 http://seattlepilots.com; Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 11, 1969; and Pilots Scorebook, April 1969, Private Collection of David Eskenazi.

26 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 21, 1969.

27 Seattle Times, July 21, 1968.

28 Ibid.

29 Bill Mullins, Becoming Big League: Seattle, the Pilots, and Stadium Politics (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 152.

30 Robert Gladstone and Associates, “Basic Economic Indicators and Development Problems and Potentials for Seattle Model Cities Program: Final Report,” Vol 2 (Seattle: 1970), 43, 57.

31 Susanne Elaine Vandenbosch, “The 1968 Seattle Forward Thrust Election: An Analysis of Voting on an Ad Hoc Effort to Solve Metropolitan Problems without Metropolitan Government” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, 1974), 85, 92.

32 Seattle Times, September 4, 1968 and Concession Agreement [Stadium Lease], file 1, Pacific Northwest Sports, Inc., Debtor, Case File 6682, United States District Court for the Western District of Washington, Northern Division (Seattle), Records of the District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21, National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Alaska Region (Seattle).

33 Seattle Times, September 19, 1968.

34 Owners’ complaints: Seattle Times, March 26-27, 1969, Seattle Post-Intelligencer February 7, 1976,, and deposition of Robert Short, folder 10, box 3, Washington v. American League, Washington State Archives, Northwest Branch, Bellingham, Washington; Kuhn’s comment: Bowie Kuhn, Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York: Random House, 1987), 91; reference to Charlie Berry: deposition of Joe Cronin, folder 4, box 3, Washington v. American League, Washington State Archives, Northwest Branch, Bellingham, Washington.

35 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 11, 1969.

36 Henry Berg to Staff, June 27, 1969, folder 11, box 2, Henry Berg, handwritten report, August 3, 1969, folder 1, box 16, and Bouillon, Christofferson, and Schairer Report, August 8, 1969, folder 21, box 1, all from Seattle Municipal Archives, City of Seattle Law Department Baseball Litigation Files.

37 Quoted in Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 31, 1969.

38 Seattle Times, October 2, 1969.

39 Deposition of Allan Selig, folder 9, box 3 in Washington v. American League, Washington State Archives, Northwest Branch, Bellingham, Washington.

40 Milwaukee Journal, April 1, 1970.

41 Carlson to supporters, November 10, 1969, Notes of contributions, November 29, 1969, and deposition of Edward Carlson, folder 3, box 3, Washington v. American League, Washington State Archives, Northwest Branch, Bellingham, Washington; and “Pilot Purchase Activities,” folder 5, box 7, Seattle Municipal Archives, City of Seattle Law Department Baseball Litigation Files.

42 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 18, 1969.

43 Danz quoted in Seattle Times, December 17, 1969; “Pilot Purchase Activities,” folder 5, box 7 and “Pacific Northwest Sports, Inc. Loan,” folder 14, box 6, Seattle Municipal Archives, City of Seattle Law Department Baseball Litigation Files.

44 Seattle Times, January 27, 1970.

45 Seattle Times, January 28, 1970.

46 Cashen in meeting transcripts, Washington v. American League in folder 9, box 5, Seattle Municipal Archives, City of Seattle Law Department Baseball Litigation Files.

47 Cronin quoted in Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 11, 1970 and brief in support of renewed motion of baseball defendants, folder 10, box 5, Seattle Municipal Archives, City of Seattle Law Department Baseball Litigation Files.

48 Deposition of Joe Cronin, Pacific Northwest Sports, Inc., Debtor, case 6682, United States District Court for the Western District of Washington, Northern Division (Seattle), Records of the District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21, National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Alaska Region (Seattle).

49 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 14, 1970 and Bowie Kuhn, Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York: Random House, 1987), 92.

50 Seattle Times, March 16, 1970.

51 Seattle Times, March 24, 1970.

52 Folder 26, box D-1, Series 491 Director’s Files, Record Group 502 Stadium Administration, King County Washington Archives.

53 Carson van Lindt, The Seattle Pilots Story (New York: Marabou Publishing, 1993), 205.

54 There is an unverified story which Steve Hovley related at the

Seattle SABR Convention, June 30, 2006. The truck carrying the Pilots’ equipment was said to have awaited word in Provo, Utah whether to turn left or turn right. When the bankruptcy court’s decision became official, the truck veered towards Wisconsin.

|

SEATTLE PILOTS EXPANSION DRAFT |

|||

|

PICK |

PLAYER |

POSITION |

FORMER TEAM |

|

1 |

Don Mincher |

1b |

California Angels |

|

2 |

Tommy Harper |

of |

Cleveland Indians |

|

3 |

Ray Oyler |

ss |

Detroit Tigers |

|

4 |

Jerry McNertney |

c |

Chicago White Sox |

|

5 |

Buzz Stephen |

p |

Minnesota Twins |

|

6 |

Chico Salmon |

2b |

Cleveland Indians |

|

7 |

Diego Segui |

p |

Oakland A’s |

|

8 |

Tommy Davis |

of |

Chicago White Sox |

|

9 |

Marty Pattin |

p |

California Angels |

|

10 |

Gerry Schoen |

p |

Washington Senators |

|

11 |

Gary Bell |

p |

Boston Red Sox |

|

12 |

Jack Aker |

p |

Oakland A’s |

|

13 |

Rich Rollins |

3b |

Minnesota Twins |

|

14 |

Lou Piniella |

of |

Cleveland Indians |

|

15 |

Dick Bates |

p |

Washington Senators |

|

16 |

Larry Haney |

c |

Baltimore Orioles |

|

17 |

Dick Baney |

p |

Boston Red Sox |

|

18 |

Steve Hovley |

of |

California Angels |

|

19 |

Steve Barber |

p |

New York Yankees |

|

20 |

John Miklos |

p |

Washington Senators |

|

21 |

Wayne Comer |

of |

Detroit Tigers |

|

22 |

Darrell Brandon |

p |

Boston Red Sox |

|

23 |

Skip Lockwood |

p |

Oakland A’s |

|

24 |

Gary Timberlake |

p |

New York Yankees |

|

25 |

Bob Richmond |

p |

Washington Senators |

|

26 |

John Morris |

p |

Baltimore Orioles |

|

27 |

Mike Marshall |

p |

Detroit Tigers |

|

28 |

Jim Gosger |

of |

Oakland A’s |

|

29 |

Mike Ferrero |

2b |

New York Yankees |

|

30 |

Paul Click |

p |

California Angels |