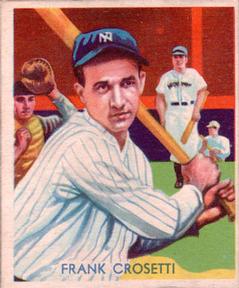

Frankie Crosetti

In 37 seasons as an infielder and third-base coach for the Yankees, Frank Crosetti was on the field for 23 fall classics, of which New York won 17. After a while “The Crow” had collected so many rings that the Yankees started giving him engraved shotguns instead. Sandwiched between Tony Lazzeri and Joe DiMaggio as one of a troika of Bay Area Italians who came to the Bronx from the Pacific Coast League in the 1920s and ’30s, Crosetti may not have been the most talented player in pinstripes – he is one of only two starting position players in his rookie season not in the Hall of Fame – but he was often the glue that held everyone together.1

In 37 seasons as an infielder and third-base coach for the Yankees, Frank Crosetti was on the field for 23 fall classics, of which New York won 17. After a while “The Crow” had collected so many rings that the Yankees started giving him engraved shotguns instead. Sandwiched between Tony Lazzeri and Joe DiMaggio as one of a troika of Bay Area Italians who came to the Bronx from the Pacific Coast League in the 1920s and ’30s, Crosetti may not have been the most talented player in pinstripes – he is one of only two starting position players in his rookie season not in the Hall of Fame – but he was often the glue that held everyone together.1

Crosetti was a consummate professional, a sure-handed fielder, and as one writer put it, “one of the most annoying .245 batters that baseball ever had.”2 Perhaps the Yankees’ success in his years with the team was no coincidence. “Crosetti is the sparkplug of the Yankees,” Rogers Hornsby once said. “Without him they wouldn’t have a chance. He is a great player and he is about the only one on the club who does any hollering.”3

Crow’s reputation as the Yankees’ “holler guy” gave secondary meaning to a moniker that superficially seemed like a shortened version of his last name. Players grew accustomed to hearing his high-pitched voice cawing from all corners of the field.

It may have come about incidentally. During a frustratingly sluggish stretch in 1932, manager Joe McCarthy told the rookie Crosetti that Lou Gehrig looked too lackadaisical at first base. “When you get the ball in infield practice,” McCarthy said, “fire it back hard at Gehrig. Holler at him. See if you can’t wake him up.”4

Obligingly, Crosetti obeyed. (“Although Gehrig was giving me dirty looks,” he recalled. “I remember him saying, ‘If I get ahold of you, I will break you in half!’ – which he easily could have done!”) Years later, McCarthy related that Gehrig was never the problem at all – it was Crosetti who had needed the extra motivation. Apparently it worked – his animated style on the field stuck.5

Off the field Crosetti had “the same approximate loquacity as the Sphinx,” as New York Times columnist Arthur Daley once described him,6 a trait he shared with the other two members of the Italian trio.

At least two oft-told stories illustrate this. In February 1936, Lazzeri and Crosetti took the rookie DiMaggio cross-country from San Francisco to St. Petersburg for spring training. The car was eerily silent for most of the three days of the trip. Crosetti and Lazzeri had taken turns behind the wheel, and toward the end of their trek, Lazzeri suggested, “Let the kid drive.” Only then did DiMaggio reveal he didn’t know how.7

Another story involved a St. Louis sportswriter who observed Lazzeri, Crosetti, and DiMaggio sitting together one day in the lobby of the Chase Hotel. Ninety minutes went by without a word until DiMaggio cleared his throat.

“What did you say?” asked Crosetti.

“Shut up,” said Lazzeri. “He didn’t say nothing.”8

The younger son of Domenico Crosetti, who emigrated from near Genoa, Italy, around the turn of the 20th century, and Rachele Monteverde Crosetti, a California native whose parents were from the same region, Frank Peter Joseph Crosetti was born in San Francisco on October 4, 1910.

Because he suffered from poor health as a toddler, the family relocated to the more rural Los Gatos, and Domenico Crosetti – who would hold a number of unskilled odd jobs, including orchardist, gardener, and scavenger – started a vegetable farm. Frank’s first baseball experiences were playing one-a-cat (a sort of hybrid of baseball and cricket) on that 12-acre plot. For a bat and ball, he and his brother, John, who was three years older, used a whittled-down board and the big end of a dried corncob.9 No member of his family had ever seen a baseball game.10

Rachele Crosetti did not object to her son playing ball, but – even into Frank’s professional days – she feared he would get hurt.11 The family matriarch ran a stern but loving household, which included early curfews and church every Sunday. But she was always waiting for the Crosetti boys after school with a sandwich and eggnog.12

“My mother was on the strict side,” Frank Crosetti wrote in 1997. “My brother and I probably resented it. But as we grew older we were thankful that she was. She was right, it kept us out of trouble, as it does not take much to go on the other side of the tracks.”13

It didn’t keep him in school, however. An unimpressive student, Crosetti, whose family moved to Santa Clara, then to the North Beach area of San Francisco, once skipped classes at Lowell High School for two weeks to watch the local Pacific Coast League team, the San Francisco Seals, play ball.14 At 16, he dropped out.

After playing semipro ball for the Butte Mining League in Montana, Crosetti played winter ball in San Francisco at the Seals’ Recreation Park, where Sam Fugazi, an unofficial Seals scout, invited him for a tryout with the professional club. The Seals appreciated Crosetti’s talent but deemed him too small to be a regular, so team executive secretary George Putnam had bottles of milk delivered to his house every morning, and Crosetti put on ten pounds.15 He wasted little time in grabbing his first headlines, hitting a grand slam off Joe Dawson of the Pittsburgh Pirates in a March 21, 1928, exhibition game against the reigning National League champions.

Crosetti batted a modest .248 in 96 games in 1928, mainly playing third base. The following year he was groomed to be a shortstop to replace Hal Rhyne, who had gone to the majors. Playing nearly the entire 180-plus-game schedule, Crosetti improved to .314 in 1929, and to .334 in 1930. In the latter season he hit 27 home runs, stole 18 bases, and led the league with 171 runs scored.

The slick-fielding leadoff hitter attracted the attention of major-league scouts, including Bill Essick of the New York Yankees. Convinced that he’d just seen the greatest shortstop in the game,16 Essick persuaded Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert to open his wallet. On August 23, 1930, Crosetti became the property of the Yankees for what eventually amounted to a handful of marginal players – Julie Wera, Bill Henderson, and Sam Gibson – and $75,000 in cash.17

Still barely 20 years old, Crosetti remained with the Seals in 1931 for more seasoning at $1,000 a month, one of the league’s highest salaries that season. He batted cleanup for the only time in his career and hit .343.

Crosetti was a “scared kid out of San Francisco”18 who could barely put a sentence together when he met his idol and soon-to-be teammate Babe Ruth on a barnstorming tour that offseason,19 but he headed to spring training in St. Petersburg in 1932 as the Yankees’ leading shortstop candidate.20 Manager Joe McCarthy drilled him hard – including subjecting him to a rigorous fielding drill in which coach Sunset Jimmy Burke would hit rapid-fire grounders just out of his reach21 – but Crosetti impressed the skipper as “one of the fastest infielders around [with] a fine, sure pair of hands.”22 Lou Gehrig liked him (“because I kept quiet and didn’t pop off”23), and double-play partner Lazzeri took him under his wing (“I looked up to him like a big brother”24).

Ultimately, McCarthy went with the veteran Lyn Lary at short and started Crosetti at third. Crosetti went 0-for-5 on Opening Day, April 12, against Philadelphia (his first big-league hit, a triple, came in the Yankees’ next game) and was benched after batting just .228 in his first 29 games. He won the shortstop job later that summer when Lary stopped hitting, but the inflated expectations stemming from his purchase price and playing in the New York City fishbowl probably dogged Crosetti a bit in those early years.

Crosetti generally balked at interviews, though when he did talk – particularly as he got older –he wasn’t shy about expressing opinions. As the last surviving member of the 1932 team, which decisively swept the Chicago Cubs in the World Series that year, he insisted that Babe Ruth had not “called his shot” in Game Three.

The Yankees may have considered trading Crosetti when Billy Werber outplayed him during 1933 spring training. Penciled in the lineup for the benefit of an interested Boston scout for a series of exhibitions as the team headed north, Crosetti turned on the spectacular, and the Yankees jacked up the price. The Red Sox took Werber for $40,000 less.25

And yet Crosetti endured relatively unimpressive seasons in 1933 and ’34, and was often in danger of losing his job to another infielder. Before the 1935 season he worked out with University of California-Berkeley track coach Brutus Hamilton to become bigger, faster, and stronger,26 and was assured by McCarthy he was the only shortstop candidate in the running.27

And he thrived – though his batting statistics were comparable to his previous season averages, he committed just 16 errors, after hovering around 40 in each of the prior two years, albeit in many fewer games.

Then on August 4, 1935, he blew out his left knee untying his shoes. Crosetti had strained it three weeks before in a collision with the White Sox’ Luke Appling, but when he pulled his leg up to get undressed in his Pullman berth that night, some cartilage tore loose and he doubled over in pain. The prognosis: season-ending knee surgery.

Team president Ed Barrow offered Crosetti an invitation to spring training the next year on a provisional $1 contract. But Crosetti not only disposed of any doubt surrounding the status of his knee – securing an $11,000 raise at the start of the season – but he put together the best offensive season of his career, batting .288 with 15 home runs, 78 RBIs, and 18 stolen bases. He was selected to the American League All-Star team.

The surgery had actually helped his batting stance. “I am turned around more,” Crosetti said. “And you will notice that I do not swing so hard. I do not fan so often. My timing is better.”28

Actually, he did strike out quite a bit – 83 times in 1936, second-most in the league, and he led the AL in strikeouts with 105 and 97 in 1937 and ’38, respectively – but he also proved why traditional statistical categories may not tell the whole story. Crosetti took tremendous pride, for instance, in consistently leading the league in hit-by-pitched-balls, which Yankees coach Art Fletcher taught him how to execute without getting seriously injured.

And even though no one kept track of on-base percentage in those days, in hindsight, his knack for getting himself aboard explains how a career .245 hitter remained successful in the leadoff spot for the Yankees’ four-straight World Series championship run from 1936 through 1939. Lifetime, Crosetti’s OBP was .341 – typically some 90 to 100 points higher than his season averages. His record of 757 plate appearances in 1938 was not eclipsed until 1962, after eight games were added to the major-league schedule.

Crosetti also mastered the hidden-ball trick, which he picked up while with the Seals from teammate-turned-umpire Babe Pinelli. The shape of the old glove, with the large hole above the wrist strap, allowed Crosetti to pretend to flip the ball to the pitcher, then quickly slip his left hand through the hole and pull the ball inside. The pitcher would fiddle with the rosin bag without returning to the rubber as Crosetti would politely ask the baserunner if he could clean the dirt from the base, tagging the startled man out as soon as he stepped off.29

Crosetti’s shining moment (and greatest thrill) as a player was the 1938 World Series, the Yankees’ second sweep of the Cubs. His defensive play, which included nailing a runner at the plate from the foul line in short left field, as well as coming “from nowhere” to turn a “certain single” up the middle into an out,30 saved three runs in the Yanks’ 3-1 victory in the opener. Crosetti’s home run off Dizzy Dean in Game Two with two outs in the eighth proved the deciding blast in the 6-3 victory. Ol’ Diz no longer had the same zip on his fastball, but he’d handcuffed the fearsome Yankees lineup on four hits – with the Cubs ahead, 3-2 – before Crosetti worked a ten-pitch at-bat into a two-run blast into the left-field seats.31 Add a two-run double and a two-run triple in Game Four, and Crosetti tallied six RBIs for the Series.

He’d been no slouch in the regular season, either, leading the league in stolen bases (27), hitting 35 doubles (ninth in the league), and setting a record for shortstops by turning 120 double plays.32 Much of his defensive success in 1938 could be attributed to the arrival of Joe Gordon at second base to replace a graying Lazzeri.

At that time Crosetti had been seeing Norma Devincenzi, whose family owned the apartment building in San Francisco where his brother, John, was a tenant. Crosetti asked her to come to Chicago for the World Series. When he subsequently had to have minor surgery in New York, she followed. He suggested that they get married, and on October 22, 1938, they quietly eloped at the Church of the Transfiguration in downtown Manhattan. Their union lasted until his death, 63 years later, along the way producing a daughter, Ellen, on October 4, 1941 (his 31st birthday), and a son, John, on October 5, 1943.33

Brimming with confidence from his marriage, his third straight championship, and another respectable year statistically, Crosetti staged a much-publicized holdout in the early days of spring training 1939, refusing to sign for less than $15,000. By mid-March, he’d caved for $14,000. In the rush to catch up in his conditioning, a process further delayed when he was hit in the leg by a thrown ball, Crosetti developed a sore arm and got off to a slow start. Eventually, he came around – and despite batting only .233, he scored 109 runs (the fourth straight season in triple digits) and was selected to the AL All-Star team (but didn’t play). He also caught the final out of the World Series, another sweep, this time of the Reds – though he went just 1-for-16 – as the Yankees took home their fourth consecutive championship.34 He received a nice raise, signing for $18,000 by mid-February.

Then, abruptly, the honeymoon ended. Despite Yankees president Ed Barrow’s new mandate that all players stay in shape during the offseason, Crosetti, determined to condition himself “slowly” so he wouldn’t develop another sore arm, passed up that advice.35 Yet again by mid-March, the sore arm returned. He couldn’t hit anything and bobbled balls on plays he would normally make. After the Yankees lost seven straight in May, McCarthy benched him for a week in favor of Bill Knickerbocker (who couldn’t hit or field much better). In August Crosetti was dropped to eighth in the batting order. The Yankees finished third and Crosetti hit .194.

Frank Graham of the New York Sun tried to excuse Crosetti’s offyear – Gordon had also been off all season, and Red Rolfe had been ill, so Crosetti “was trying to cover too much territory on legs that had been pounding the big-league trail for nine seasons.”36 But the talk now shifted to some kid named Phil Rizzuto who’d been tearing up the Yanks’ Kansas City farm club. Only timing – the looming possibility that young, unmarried players like Rizzuto might be sent off to war – probably saved Crosetti from being dealt to another club that offseason.37

Determined to keep his job, Crosetti had worked furiously to stay in shape, running up the steep hills of San Francisco. He experimented batting left-handed in spring training, hoping it would raise his average.38 And yet, while many of Crosetti’s loyal teammates initially gave the usurper Rizzuto the cold shoulder, Crosetti actively helped the diminutive youngster. He taught Rizzuto how to position himself on each pitch, and how to bluff a bunt. He let him in on the secrets of being hit by a pitch and how to pull off the hidden-ball trick. “He made me look good – and here I am trying to take his job away,” Rizzuto recalled years later.39

Rizzuto won the starting spot, but when he wasn’t hitting by May, the Crow was waiting in the wings to reclaim the position. Then, on June 16, Crosetti was spiked in the throwing hand by Cleveland’s Hal Trosky and had to miss some time, and Rizzuto took over again, for good. Crosetti found playing time later in the season at third base when Red Rolfe was hospitalized with chronic ulcerative colitis – but all told, his role was limited to 50 games. On the bench all five games of the Yankees’ World Series victory over the Dodgers, Crosetti did what he did best off the field – he played the holler guy again.

The now reportedly “aging” Crosetti (he was only 31, but maybe his thinning hairline had something to do with it) broke camp as a utility infielder in 1942. He worked some with young Jerry Priddy, Rizzuto’s minor-league partner up the middle who was being groomed for third base to replace the ailing Rolfe, but Priddy’s bat stayed cold, and Crosetti became the starting third baseman. He did a formidable enough job that some Yankees were indignant that he didn’t make the AL All-Star team. McCarthy, the AL manager, admitted that had he the choice, he would have chosen Crosetti over Cleveland third baseman Ken Keltner, but the Yankees already had nine representatives, and “we have no right to squawk over the omission of a tenth.”40

Rolfe displaced Crosetti when he returned later that summer. Crosetti did get into the third game of the World Series, which the Yankees lost to the Cardinals. Playing third base, he shoved umpire Bill Summers over what he considered a bad call. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis fined Crosetti a reported $250 and suspended him for the first 30 days of the 1943 season.

In February 1943 Crosetti’s father, Domenico, was struck by a car and killed. Barrow gave Crosetti permission to report to camp late, on April 10, to spend more time with his family. He didn’t report until the beginning of May, however, due to a dispute over whether the Yankees should pay him for the first month of the season.41 Barrow capitulated42 – with the war sapping teams of talent, Crosetti would be needed to help fill the void left when Rizzuto joined the Navy. A bout with the flu days before his suspension ended left Crosetti weak and out of shape, however, and rookies Snuffy Stirnweiss and Billy Johnson had the left side of the infield covered. Crosetti’s return on May 21 went by almost unnoticed.

Still, Barrow and McCarthy recognized Crosetti’s value on the bench, almost as a secret weapon. Despite continued interest from other teams over the years, Barrow refused to sell him. “I don’t care how much they offer,” Barrow said. “Nobody can buy Crosetti. He stays with the Yankees as long as I have anything to do with running them.”43 The feeling was mutual – for Crosetti, it was “the Yankees – or nothing.”44

When Stirnweiss stopped hitting, Crosetti was back at short – and the Yankees turned a slim league lead into double digits for another pennant and a successful World Series rematch with the Cardinals. Crosetti reached base in each of the five games (5-for-18 with two walks), started the winning rally in the sixth inning of Game One with a leadoff single to center, and made game-saving defensive plays in Games Four and Five.

Working in a shipyard in Stockton, California, in the offseason gave Crosetti an occupational draft deferment as a defense worker, but tied him to his job. All he could do was wait patiently, playing semipro ball once or twice a week. When the draft board eased restrictions on men over 30 in July 1944, Crosetti jumped on a train to rejoin the Yankees, who hoped his presence would lead them to another pennant.45 It didn’t, but it gave Crosetti leverage when negotiating his 1945 contract. Again a late holdout, Crosetti signed for $15,000 two weeks before Opening Day. He didn’t have the greatest season, but he was better than the alternative – Joe Buzas, who had iron hands.46

At 35, Crosetti was slowing down; the war was over, and Rizzuto and the rest of the major-league talent had returned. Crosetti batted.288 in 28 games off the bench in 1946. But his limited role was somewhat convenient, as the Yankees started traveling out west by airplane, and he was afraid to fly. (“It took me too long to accumulate what I have, and I am in no hurry to go where I can’t spen[d] it,” he said.47) He was granted permission to follow the team around by train.

Crosetti signed as a player-coach alongside new manager Bucky Harris for 1947 and got into three games, going hitless in his only at-bat. He went on the inactive list late that summer when the Yankees called up Jack Phillips and Allie Clark. He was making calls to the bullpen on Harris’s behalf when the Yankees beat the Dodgers in the World Series.

At his request, Crosetti reported to spring training in 1948 as a player, not as a coach, though even that spring he was helping teammates, such as perfecting pitcher Joe Page’s slider so that, as Page put it, it didn’t “tear my arm apart.”48 He played in 17 games, in the last of which, on October 3 in Boston, he appeared as a defensive replacement at second base.

After that season – and for the next two decades – Crosetti coached full time. He waved home more than 16,000 men from the third-base coaching box and helped a slew of infielders realize their big-league talent. He also taught pitcher Ryne Duren – a hard-throwing, bespectacled righty whose control was purportedly as bad as his vision – to intimidate batters by firing his first warm-up pitch high over his catcher’s head.

He was crafty in other ways, too. According to Rizzuto, “He could steal signs, and knew from the way the pitcher was holding the ball what he might be throwing, a curve or a fastball, and he’d be able to relay it to the batter.”49

Crosetti lived in a somewhat old-fashioned manner – rising with the sun at 6 A.M., the first one in the clubhouse and the last one out, retiring no later than 9:30 or 10 P.M. (unless there was a night game). Baseball was all that mattered.

Whitey Ford recalled that after one long night of debauchery during spring training he returned to the hotel in Palm Beach with Mickey Mantle and Hank Bauer at 6:30 on a Sunday morning – in time to run into Crosetti on his way to church. When Crosetti asked where they’d been, they sheepishly said they’d just come from Mass. “He looked at us and laughed and went to church,” Ford said. “Cro was a great guy. We didn’t have to worry about him squealing.”50

Yet when it came to behaving in a professional context, many saw Crosetti as being too tightly wound. He wouldn’t hesitate to call out players for making mistakes if he thought they were not giving their all. When Phil Linz’s infamous harmonica playing amid a losing streak started a fracas on the team bus in 1964, Crosetti had little sense of humor about it, calling it the worst thing he’d ever witnessed in all his years with the club.51

And he hardly hid his disdain for the media or anything involving spectacle – pitcher Jim Bouton, who skewered him in his baseball exposé Ball Four, wrote that Crosetti’s “twin fortes” were “saving baseballs … to the point of jumping into the stands after them, and chasing photographers off the field.”52 Wrote Dan Daniel of Crosetti’s reaction to seeing a pregame dog show on the field at Yankee Stadium: “His comments cannot be printed.”53

Even after the Yankees would win the World Series, Crosetti wouldn’t stick around to celebrate, preferring instead to jump into a car the next day and begin the drive back to Stockton to be with his family. In the offseason, he enjoyed fishing and hunting, biding his time until he could head to Florida for spring training.

When the Yankees needed a guide for young players first joining the team, they had Crosetti pen the 12-page pamphlet. It covered such topics as staying in peak physical condition, eating and sleeping well, hustling, keeping one’s temper, and obligations as a teammate and as a public figure – which included choosing one’s friends wisely and avoiding the temptations of drinking, carousing, gambling, and loose women. “It takes a man to say no, and it takes a man to realize 100% of his baseball is potential,” he wrote, leaving one to wonder a bit about the wording.

In 1966 Crosetti published a youth instructional book titled Frank Crosetti’s Secrets of Baserunning and Infield Play. It wasn’t high literature, but, unlike many other books written by professional athletes, the words were all his, and not those of a ghostwriter or “co-author.”54

Some called Crosetti the “perfect coach,” because he never had any ambition whatsoever to manage.55 He repeatedly spurned rumors that he was taking over for Casey Stengel (“I would not be manager of the Yankees if the job were offered to me.”56), and also turned down offers to manage other major- and minor-league clubs.57

“You have to worry about 25 guys and make speeches and give out interviews and that doesn’t appeal to me,” Crosetti said. “Besides, who manages forever? You have a bad year, or don’t win when the management thinks you should, and you’re gone. Then how do you know you can get another job?

“I’ve been perfectly happy right where I am … at third base. You don’t get a fat salary but you don’t have problems either.”58

As when he was a player, though, he refused to accept being short-changed. Crosetti was the ringleader in a 1962 suit filed on behalf of a couple of hundred contemporaries against the owners’ pension committee. The Major League Baseball Players’ Association, propelled by lucrative television and marketing deals, had met secretly the previous fall to raise the per-month pension rate to $250; players already retired more than ten years, however, like Crosetti, were frozen at $175. The players lost the suit and eventually settled for $750,000. Decades later, Crosetti was also one of a handful of old-time ballplayers who unsuccessfully brought what they hoped would be a class action against Major League Baseball for using their names and images in promotional materials.59

Not that Crosetti was ever in dire straits financially. His World Series checks alone totaled a reported $142,989.30 – a stunning amount in an era when season salaries were still in the low five figures. He had also made a small fortune off shrewd real-estate investments – something he began doing while with the Seals when a banker friend advised him to acquire all the local real estate he could find in Depression-era San Francisco.60

By 1968, though, the Yankees’ World Series bounty had dried up, and Crosetti longed to spend more time with his mother, children, and grandchildren on the West Coast. On October 4, his 58th birthday, he submitted a six-page handwritten letter of resignation.

“I was probably around too long anyway and people were getting tired of looking at me,” he wrote. “They say a change once in a while is good for everyone – gives you a new lease on life.”

He concluded: “This is not a good-bye – as I hate good-byes. Only a ‘I’ll see you later.’ Come spring, the Cro will be back – only in another uniform. The old saying of years gone by probably will hold true of me also, ‘Once a Yankee, always a Yankee!’”61

Specifics were unspoken in the letter, but Crosetti had all but signed to coach the expansion Seattle Pilots in 1969, thousands of miles closer to his home in Stockton, California. He grew fond of the Emerald City – despite there not being “enough traffic going around third base to suit me” for the victory-challenged Pilots62 – and had planned on eventually transitioning into a scouting role with the organization. But Seattle finished dead last, and general manager Marvin Milkes, after supposedly promising Crosetti that he’d be there for more than one season, didn’t renew his contract.63 Crosetti felt betrayed, but before Christmas he’d been recruited by the Minnesota Twins.

Crosetti was in the coach’s box along third as the Twins won the AL West division (and lost to Baltimore in the League Championship Series) in 1970. And he was there to shake hands with Harmon Killebrew for the slugger’s 500th home run in 1971. Crosetti rarely shook hands after a player hit a round-tripper – Mickey Mantle’s walk-off home run in the 1964 World Series and Roger Maris’ 60th and 61st homers in 1961 being three other notable exceptions.

But after two seasons, he’d truly had enough. He retired and coached high-school ball – leading St. Mary’s in Stockton to a 16-game undefeated season in 1972.

Although he never attended a Yankees Old Timers Day after he retired, Crosetti avidly followed the team from his home in Stockton and was a frequent visitor when the Yankees played Oakland each year, even appearing in the broadcast booth on occasion. Until a broken hip from a fall incapacitated him in January 2002, he went fishing regularly, and he rarely shied away from an opportunity to talk baseball or reminisce about his years in Pinstripes with those who would listen.

“He was Yankee all the way around,” his wife, Norma, said after he died at age 91 on February 11, 2002. “He had no other team.”64

The “old saying” had indeed held true.

This biography appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin. An abbreviated version was first published in “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz.

Sources

Special thanks to the Baseball Hall of Fame for providing me a copy of Crosetti’s player file, to Lawrence Baldassaro for sharing his research, and to Crosetti’s grandson Michael McCoy for tracking down relatives to answer questions about his grandparents’ history. All statistics, unless otherwise noted, are from baseball-reference.com.

Telephone interview by Ellen Biggs, Frank Crosetti’s daughter, with Thomas Bourke on November 20, 2011.

Notes

1 The Yankees lineup in the 1932 World Series featured Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, Earle Combs, Joe Sewell, and Bill Dickey (not to mention Red Ruffing, Lefty Gomez, and Herb Pennock on the mound). Ben Chapman was the other position player not enshrined in Cooperstown.

2 Arthur Daley, “End of the Trail,” Sports of the Times, New York Times, January 20, 1947.

3 Daniel M. Daniel, “A Shoestring, A Slip and an Injured Right Knee Made Crosetti Yanks’ Musketeer Number Three,” New York World-Telegram, May 21, 1936.

4 Frank Crosetti as told to Al Hirshberg, “I Coach the Hot Corner,” Saturday Evening Post, August 8, 1959.

5 Ibid.

6 Arthur Daley, “End of the Trail.”

7 “Crosetti still has great range,” Sweet Spot, December 1996/January 1997, Crosetti HOF file

8 Richard Goldstein, “Frank Crosetti, 91, a Fixture In Yankee Pinstripes, Is Dead,” New York Times, February 13, 2002.

9 Gary Klein, “Frank Crosetti, 91; Yankee Player, Third-Base Coach,” Los Angeles Times, February 13, 2002.

10 “Crosetti Eagerly Looks Forward To Joining Yankees This Spring,” Associated Press report in New York World-Telegram, January 11, 1932.

11 Profile, New York Mirror, April 10, 1937.

12 Handwritten letter to “Richard,” dated January 25, 1997. [Screenshot from eBay, but verified by Michael McCoy, Crosetti’s grandson, to be his handwriting.]

13 Ibid.

14 Gary Klein, “Frank Crosetti, 91.”

15 Ed R. Hughes, “Frisco to Fatten Up Gaunt Young Pitcher,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1929.

16 Daniel, “Lou Gehrig, on Hitting Spree, Sets Flag Pace for Yankees,” New York World-Telegram, June 18, 1935.

17 To put the amount spent on Crosetti in perspective – not that one can compare player purchases – Lefty Gomez had been acquired by the Yankees in 1929 (two months before the stock market crashed) for a mere $45,000.

18 Joseph M. Sheehan, “A Proper Yankee,” Sports of the Times, New York Times, August 12, 1957.

19 “Crosetti Eagerly Looks Forward To Joining Yankees This Spring,” Associated Press report in New York World-Telegram, January 11, 1932.

20 Tom Meany, “Crosetti Leading Candidate For Yankee Shortstop Berth,” New York World-Telegram, March 9, 1932.

21 Tom Meany, “Crosetti and Saltzgaver Pass Critical Yankee Test,” New York World-Telegram, March 3, 1932.

22 Meany, “Crosetti Leading Candidate For Yankee Shortstop Berth.”

23 Stan Isaacs, “The 37 Seasons of Frank Crosetti,” Out of Left Field, Newsday, April 9, 1968.

24 Paul Votano, Tony Lazzeri: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005), 172.

25 Daniel M. Daniel, “A Shoestring, A Slip and an Injured Right Knee Made Crosetti Yanks’ Musketeer Number Three,” New York World-Telegram, May 21, 1936.

26 Daniel, “Lou to Stay At No. 4 in New Lineup,” New York World-Telegram, March 12, 1935.

27 Daniel, “Yank Midway Combination May Rank Best in League,” New York World-Telegram, April 6, 1935.

28 Daniel, “A Shoestring, A Slip and an Injured Right Knee.”

29 Leo Trachtenberg, “Mr. Yankee, Frank Crosetti,” Yankees Magazine, October 16, 1986.

30 “Crosetti New Hero of Yankees,” United Press report in New York World-Telegram, October 6, 1938.

31 The oft-repeated story goes that as Crow was rounding the bases, Dean shouted, “Betcha ya couldn’t a done that when I was good!” to which Crosetti responded, “You’re damn right I couldn’t.” See Arthur Daley, “The Durable Crow,” Sports of the Times, New York Times, November 7, 1960. According to Crosetti, however, the exchange never took place. “At least I didn’t hear him,” he recalled years later. “I was running with my head down. But it was true – I never could have gotten a loud foul off him when he had his fast ball.” Dick Gordon, “Crosetti Vividly Remembers Glory Years of the Yankees.” Baseball Digest, September 1970.

32 He also led AL shortstops in chances (905) and putouts (352); then again, he tied with Senators third baseman Buddy Lewis for the league lead in errors (47).

33 Several newspapers reported that the owner and operator of the PCL Oakland Oaks at the time, Victor “Cookie” Devincenzi, was Mrs. Crosetti’s brother. However, when Crosetti’s grandson, Michael McCoy, addressed the matter with his grandmother (in her late 90s in the fall of 2011), she said that none of her brothers ever worked in baseball.

34 Crosetti was also the first player to score on the infamous “Lombardi’s snooze” play, in which Charlie Keller collided with Reds catcher Ernie Lombardi at home and knocked the ball from his hands. Crosetti, waiting on the other side of the plate, had motioned for Keller to slide. Dick Gordon, “Crosetti Vividly Remembers Glory Years of the Yankees,” Baseball Digest, September 1970.

35 Daniel, “Crosetti Sees Good Season,” New York World-Telegram, March 2, 1940.

36 Frank Graham, Setting the Pace, New York Sun, January 16, 1941.

37 Dan Daniel, Daniel’s Dope, New York World-Telegram, November 27, 1940.

38 Apparently, Crosetti had originally batted lefty in semipro, until his brother informed him of a demand for right-handed hitters. “Crosetti Switches at Bat,” New York World-Telegram, March 13, 1941.

39 Leo Trachtenberg, “Mr. Yankee.”

40 Daniel, “Yanks Favor Crosetti for All-Star Berth,” New York World-Telegram, June 26, 1942.

41 Crosetti had found a loophole – the baseball rulebook allowed a team to suspend a player for insubordination without pay, but the Yankees hadn’t suspended him; the commissioner did.

42 Rud Rennie, “McCarthy’s Susp[ects?] To Report to Club,” New York Herald-Tribune, April 20, 1943. Clipping from Crosetti’s HOF File with part of the headline cut off

43 Joe Williams, “Barrow Rates An Assist for Keeping Crosetti,” New York World-Telegram, October 14, 1943.

44 Daniel, “Johnson Earns Yank Spurs,” New York World-Telegram, June 22, 1943.

45 Crosetti’s presence was so crucial that a group of Canadians wrote to Commissioner Landis protesting the “possible psychic effect” Crosetti would have on opponents; Crosetti was the “property of the United States Government,” and the Yankees had “no business whatsoever obtaining unfair help.” Letter from W.L. Brown to Commissioner Landis, September 4, 1944, Crosetti HOF player file.

46 Buzas started the first 12 games of the 1945 season at short, made six errors, and never used his glove in a major-league game again.

47 Dan Daniel, “Yankees, Dodgers, Giants Leaders In Air Argosies,” New York World-Telegram, February 15, 1947.

48 Daniel, “Cards Still Haven’t Seen Page’s Top Series Form,” New York World-Telegram¸March 17, 1948.

49 Leo Trachtenberg, “Mr. Yankee.”

50 “Crosetti still has great range,” Sweet Spot, December 1996/January 1997, Crosetti HOF file.

51 According to David Halberstam in his book October 1964 (New York: Random House, 1995), 283, Crosetti was not happy that Linz subsequently received an endorsement deal from a harmonica company – and from then on, when Crosetti would hit fungoes to fielders before the game, he would avoid hitting them to Linz. And Linz had little love for Crosetti, feeling that the coach held a double standard – riding hard the players who weren’t stars, but allowing the Mickey Mantles and Whitey Fords to do as they pleased.

52 Jim Bouton, Ball Four (New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1971), 22.

53 Daniel, “Frisco Product Proven Maestro,” New York World-Telegram & Sun, March 9, 1957.

54 Til Ferdenzi, “Crosetti Can Write Like Pro, And His New Book Proves It,” New York Journal-American, July 2, 1966.

55 Harry Grayson, “Crosetti Most Typical Yankee,” NEA wire report in New York World-Telegram & Sun, October 3, 1957.

56 Dan Daniel, “Three Managers on Shaky Side,” New York World-Telegram & Sun, October 12, 1951.

57 Daniel, “Yankees Not Interested in Rudy York,” New York World-Telegram, February 4, 1948 (turning down an offer to manage the Seattle PCL club); “No Orioles for Frank,” New York World-Telegram & Sun, September 10, 1954 (turning down an offer to manage the Baltimore Orioles); John Carmichael, “Crosetti Happy To Remain Coach,” Pittsburgh Press, April 1, 1967 (turning down an offer to manage Newark when it was a Yankees farm club). Crosetti did, however, take over as manager temporarily every so often, such as when Ralph Houk was suspended for seven games in 1961 after a tiff with an umpire. “Leaves from a Fan’s Scrapbook,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1961.

58 John Carmichael, “Crosetti Happy To Remain Coach,” Pittsburgh Press, April 1, 1967.

59 The suit, Gionfriddo v. Major League Baseball (2001), was filed in a California court by Al Gionfriddo, Pete Coscarart, Dolph Camilli, and Crosetti – four high-profile ballplayers active before 1947, when a clause was inserted into all players’ contracts to allow their image to be used commercially. They lost because the court concluded that “the public interest favoring the free dissemination of information regarding baseball’s history far outweighs any proprietary interests at stake.”

60 Daniel, “Frisco Product Proven Maestro,” New York World-Telegram & Sun, March 9, 1957. The friend was Amadeo Giannini, who founded what is now Bank of America.

61 Jim Ogle, “Crosetti Ends 37 Years in Yankee Uniform,” Newark Star-Ledger, April 19, 1968. Ogle was one of a handful of writers who suggested that the Yankees retire Crosetti’s No. 2, which he had worn since 1945. “Ahh, that’s a lot of bull,” Crosetti told Newsday’s Stan Isaacs. “… I don’t think any number should be retired. Maybe Ruth’s – that’s all because he was special – but the other numbers should be passed on to young players.” Stan Isaacs, “The 37 Seasons of Frank Crosetti,” Out of Left Field…, Newsday, April 9, 1968. Fitting that the number would eventually land with another great Yankees shortstop, Derek Jeter.

62 Joseph Durso, “Crosetti Returns to Stadium Soil,” New York Times, June 14, 1969.

63 It was probably just as well, since the team would move to Milwaukee a few months later.

Full Name

Frank Peter Joseph Crosetti

Born

October 4, 1910 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

February 11, 2002 at Stockton, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.