The Forgotten Winning Streak of 1891

This article was written by Bob Tiemann

This article was published in 1989 Baseball Research Journal

Ranking with the 1951 Giants and the 1978 Yankees, the Boston Beaneaters won 18 straight to win a National League pennant in a stirring and controversial comeback.

Although their 18-game winning streak in 1891 is ignored by most record books, the Boston Beaneaters won the National League pennant with one of the most dramatic and controversial stretch drives in baseball history. On September 15, with just sixteen playing dates left in the season, Boston trailed Chicago in the standing by 6½ games. Then Boston won 18 games in a row to leap to the pennant by 3½ games. The victory, however, was accompanied by suspicion and accusations. Chicago complained that Boston had played four doubleheaders, which required special permission from the rest of the league. There was also evidence to suggest that the other Eastern clubs had purposely lost many of their games with Boston. That evidence looks convincing nearly a century later, but the 1891 pennant still belongs to Boston.

The Beaneaters got off to a slow start, playing below .500 ball as late as June 10. Then a nine-game winning streak vaulted them into the race. Their chief competition came from the veteran New York Giants squad and the upstart Chicago Colts, led by forty-year-old Adrian C. (Cap) Anson. The Giants exchanged the lead with the Colts six times in July, but the Beaneaters kept inching closer to the top. On the morning of August 15, only four percentage pints and one game separated the three leaders. Then Chicago ran off 11 consecutive victories to pull away.

By early September, Chicago seemed sure to win the National League pennant. On the fourth, Anson was feeling so frisky that he showed up at the game wearing a white wig and a false beard that flowed down over his ample chest. To the delight of the Chicago crowd, he wore the costume for the entire game and his Colts beat the Beaneaters 5-3. At that point, Chicago had a 70-41 record and a seven-game lead over second-place Boston, which was at 62-47.

The Beaneaters salvaged the final game in Chicago but were still far behind as they headed home for the last four weeks. With first baseman Tommy Tucker swinging a hot bat, the Beaneaters won three of four from Cleveland and three straight from Cincinnati during the next week.

On September 14, the Chicago Colts came to town for the final three games between the two contenders. After the Colts won the opener, 7-1, the Chicago Tribune crowed, “The good captain’s men are champions and no mistake.” After another victory in the second game, the Tribune claimed that even “the Boston cranks [fans] give it up.” Anson was jolly enough to give a billiards demonstration in South Boston that evening.

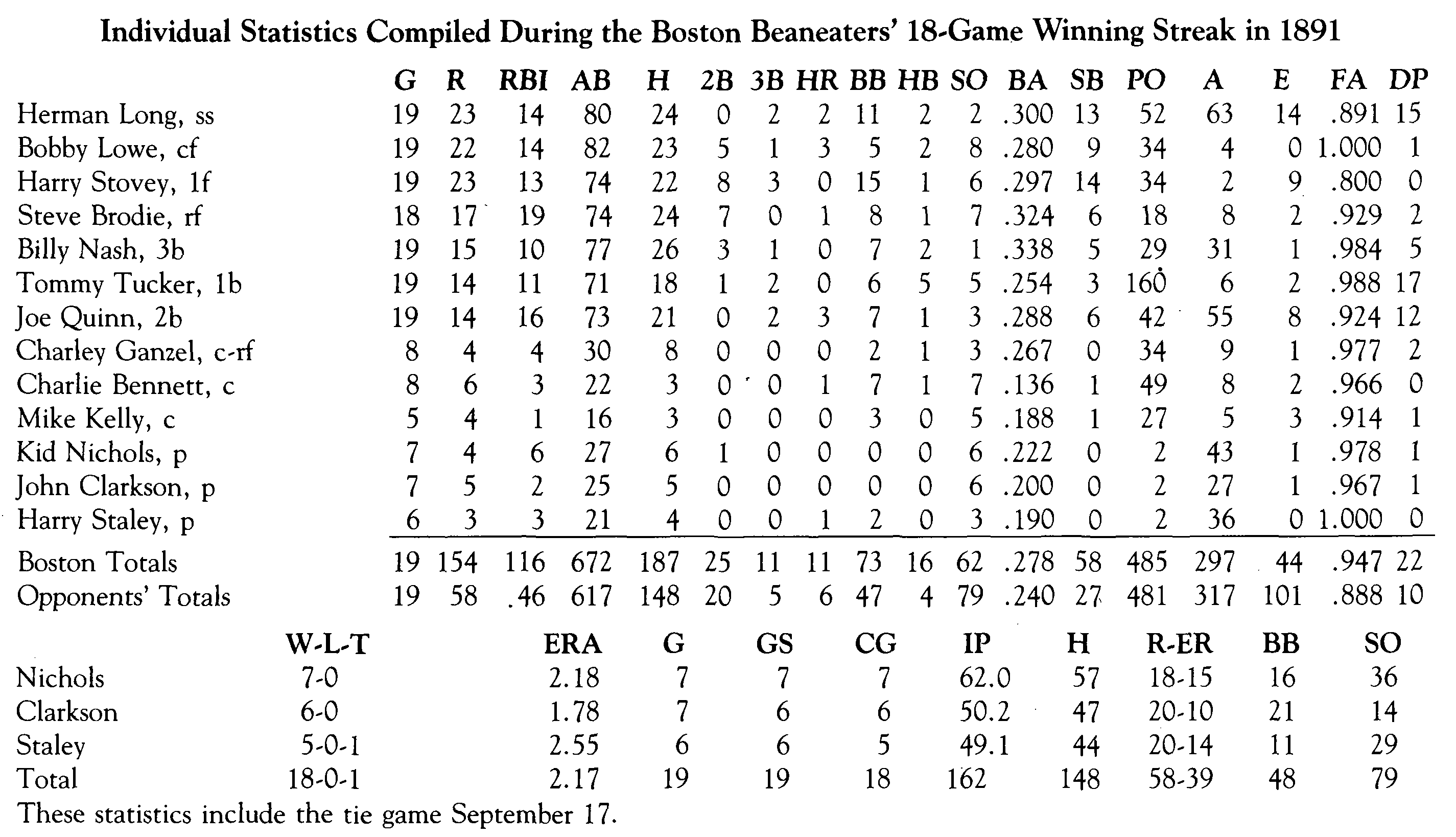

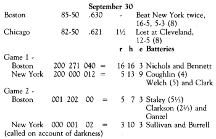

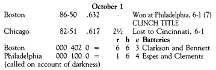

The morning newspapers on Wednesday, September 16, showed Chicago leading the league with a 76-44 record, while Boston was second at 69-50. In the Boston Globe, Tim Murnane, a player-turned-sportswriter, exorted Beaneater manager Frank Selee to “wake up your hired men and make them hustle for old Anson’s scalp.” But the prospects for the final game of the series were not encouraging. Boston was scheduled to pitch Charles ‘Kid’ Nichols whose lifetime record against Chicago was 0-9. His opponent, Hutchison, had already beaten Boston eight times in 1891. Yet it was in those inauspicious circumstances that the Beaneaters launched their long winning streak. A day-by-day account of the streak follows: (Note: At the time the home team had the choice of batting first or last.)

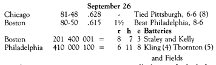

September 16

Chicago 76-45 .628 – Lost to Boston, 7-2

Boston 70-50 .583 5½ Beat Chicago, 7-2

r h e Batteries

Boston 000 211 111 = 7 10 1 Nichols and Bennett

Chicago 100 100 000 = 2 8 7 Hutchison and Shriver

According to the headline in the Globe, “Nichols was on his pitch” and was backed by fine fielding. Doubles by Harry Stovey and Bobby Lowe, a triple by Tommy Tucker, and a homer by Charlie Bennett led to runs.

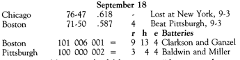

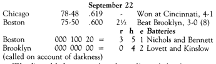

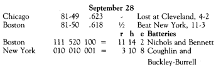

September 17

Chicago 76-46 .623 – Lost at New York, 3-1

Boston 70-50 .583 5 Tied Pittsburgh, 7-7(10)

r h e Batteries

Boston 200 100 004 0 = 7 11 2 Staley and Ganzel

Pittsburgh 103 000 210 0 = 7 11 5 Galvin and Miller

Boston was lucky to gain a tie in this game, scoring four runs in the ninth aided by three errors and a base on balls. Charley Ganzel got the key hit in the rally. Darkness halted the game an inning later. This was no way to start a winning streak, but at least Chicago lost and was held to six hits by Amos Rusie.

Mark Baldwin pitched like a man “drawing salary on suspicion,” much to the chagrin of his foghorn-voiced batterymate, George Miller. Fly balls hit to rightfielder Bud Lally were “as good as hits,” and Baldwin’s own throwing error allowed Boston to score the go-ahead run. John Clarkson “didn’t pitch a speedy ball during the game,” but his slow drops, curves, and changeups baffled the Burgers. John Ewing and the Giants beat Chicago.

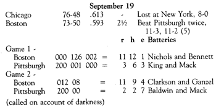

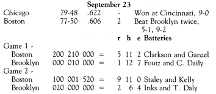

Pittsburgh scored early in each game, but Boston won both with ease. Herman Long hit a two-run home run in the first game, and little Joe Quinn hit a three-run homer over the right-field fence in the opener and a grand-slam over the left-field fence in the nightcap. (The fences down both lines at South End Park were notoriously close.) In New York, the Chicagos succumbed to Rusie again, losing on just three hits.

Sunday, September 20, was an off day, since the National League forbade Sunday ball.

Harry Staley “put on the steam” and handcuffed the Bridegrooms. Lefthander Bert Inks also pitched well until the eighth, when captain John M. Ward booted a double-play ball. Inks then failed to cover first base on a grounder to the right side, Ward let a throw go through him, and Staley capped the five-run rally with a home run. In Cincinnati, the Colts rallied to edge the Reds.

Ward’s wild throw to the plate allowed the first run to score, and Bennett’s two-run single clinched the victory. Brooklyn could do nothing with Nichols’ delivery. Chicago beat Cincinnati, behind Torn Vickery’s four-hitter.

Boston won a pair as “Brooklyn stumbled about like a drunken man on stilts.” Six Bridegrooms were caught napping on the bases in the first game, and shortstop Fred Ely made four errors. In the nightcap, Long of Boston scored from first base on a misplayed bunt and from second on an infield tap. Chicago won its third straight.

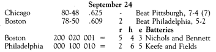

The Phillies presented a weak nine, with catcher Jack Clements and first baseman Willard Brown both hurt. Charles Esper, the only Phillie pitcher with a winning record against Boston for the season, was not even brought along on the trip. Still, Tim Keefe baffled the Beaneaters with his change of pace and would have shut them out with decent support. As it was, bad errors by Sam Thompson, Billy Hamilton, and Ed Mayer gave Boston its runs. Chicago rallied to beat Pittsburgh.

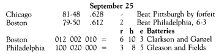

Fielding once again made the difference. An “old-gold muff” by Phillie first baseman Jerry Denny and two wretched throws by third baseman Mayer gave Boston five of its runs. Chicago won by forfeit when Pittsburgh refused to remove an ejected player. The Boston Reds, in the other league, mathematically clinched the American Association pennant with a victory in Baltimore.

The Bostons were once again “pulled out of a hole by their opponents’ errors.” Mayer was shifted to shortstop, where he contributed two errors. Catcher Jocko Fields, not to be outdone, made four, including two on throws to the plate. John Thornton pitched one-hit relief after rookie Bill Kling had been routed, but it was too late.

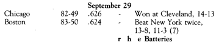

The Giants arrived in Boston accompanied by manager Jim Mutrie and club president John B. Day. Day quickly held a conference with Boston president Arthur H. Soden. The Giants had failed to bring their two best pitchers, Amos Rusie and John Ewing, and their slugging first baseman Roger Connor. Ewing was nursing a sprained ankle. Connor had been given a day off to attend to personal business in his home town of Waterbury, Connecticut. And Rusie, who had beaten Chicago twice in three days a week before and had pitched both games of a doubleheader on September 26, was allowed to go home a week early, Day and Mutrie agreeing that “he was entitled to a rest.” In the opening game of the series, according to Sporting Life, “the New Yorks beat all records for indifferent and rocky playing.” Even the Boston partisans were disgusted and roundly hissed the visitors’ work. Meanwhile, Cy Young snapped Chicago’s winning streak.

Boston had no trouble winning both games, since the Giants’ work was so dubious as to threaten baseball’s “present high standing among outdoor games.” Connor was again absent; this time the excuse was a train wreck. For Boston, Long and Lowe both scored three runs in each game. Stovey went four for five in the opener and hit a three-run triple in the nightcap.

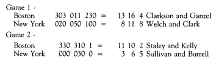

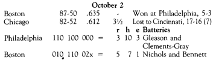

Boston took over the league lead with a double victory. Connor was finally in the New York lineup, but the Giants still “played without much heart.” In the second game they had four men thrown out at the plate and two cut down at third. The Beaneaters played spirited ball, led by four hits each by Quinn and Steve Brodie. Chicago lost to Young and Cleveland again, but filed a protest against the doubleheaders in Boston. Club president James A. Hart made no outright accusations of crookedness, but he did say, “Things look suspicious.”

Although the Beaneaters were finally facing a team fielding its strongest nine, they were still able to come out ahead. Shortstop Long was brilliant, turning five double plays in seven innings and contributing a timely single in the four-run fourth. Tucker poled a triple in the same frame but had to come out for a pinch runner. When it was announced that the usually boisterous Tucker was sick to his stomach, a wag in the bleachers yelled, “So were we when Tommy was coaching,” bringing a roar of laughter from the stands and benches alike. Chicago was whipped by Cincinnati, and Boston had clinched the pennant with two games still to play.

League president Nick Young addressed the Chicago protest by reviewing the rule about double games. Since only six teams needed to approve additional games, Chicago need not have been asked or informed before the event. Then Young admitted that the league president need not be informed either. Still, he assumed that Boston president Soden had “amply protected himself.”

The Beaneaters made it 18 in a row. In the top of the fifth, two Phillies were thrown out at the plate while in the bottom Long circled the bases on errors. A double by Nichols drove in the go-ahead run in the eighth.

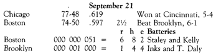

![]()

The streak ended when King Kelly allowed three passed balls and made four errors to hand the game to the Phillies. But there were still the protests and accusations to be dealt with. President Hart of Chicago said that the Eastern teams had deliberately lost to Boston to deprive Chicago of the pennant. The Colts had one of the lowest payrolls in the league, and the high-salaried Easterners did not want the humiliation of losing the pennant to Captain Anson’s youngsters. Furthermore, Anson had stood steadfastly against the late, lamented players’ Brotherhood, and the old Brotherhood boys resented this. Both the Boston and New York correspondents of The Sporting News agreed that the Giants, at least, had deliberately “laid down” against the Beaneaters. As for the protest about double games, Soden told Sporting Life on October 1 that he held telegrams of consent from six clubs. But the Boston Globe’s interviewer was convinced that Soden did not actually have such telegrams.

Investigations were ordered. The first was made by the New York club, concerning its own doubtful player absences in the Boston series. Not surprisingly, the club exonerated itself. When the league’s board of directors looked into the matter in November, the New York report was accepted. Apparently Soden also was able to produce sufficient authorization for the protested double games as well, so all charges were dismissed and the pennant officially awarded to Boston.

But the odium remained. The Boston fans held the Reds in generally higher esteem than they held the Beaneaters, especially since Soden and his partners absolutely refused to have their team meet the AA champs in a World Series. Nine years later Anson wrote in his autobiography that “a conspiracy was entered into whereby New York lost enough games to Boston to give the Beaneaters the pennant.” And even today, the tainted 18-game winning streak, tied for fifth longest in National League history, is generally left out of the record books.

(Click image to enlarge)