The Halifax and District League: Postwar Baseball in the Maritimes, 1946-1960

This article was written by Colin Howell

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

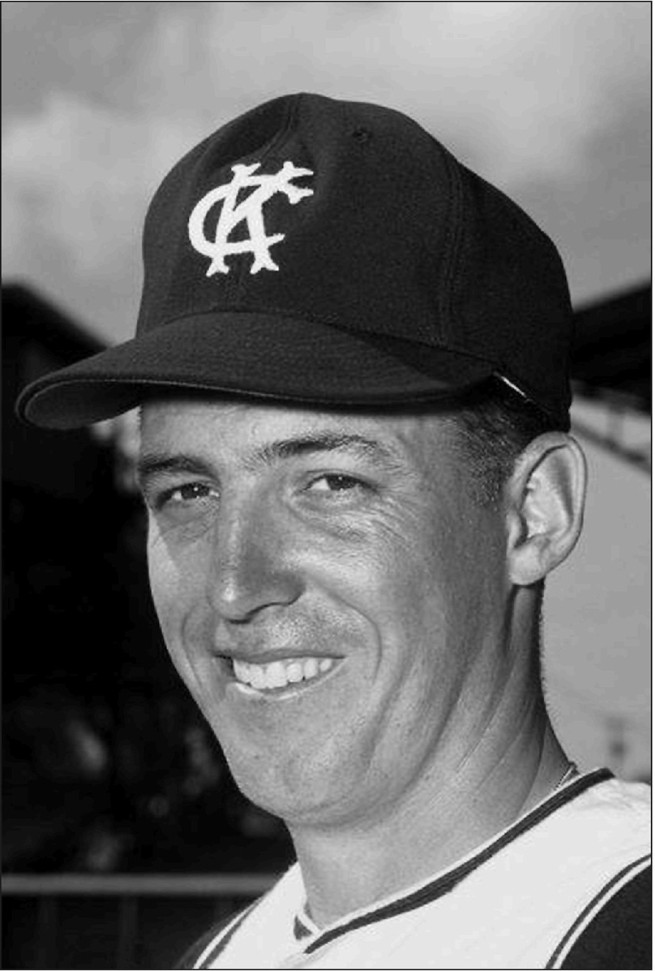

Prince Edward Island native and H&D League alumnus Vern Handrahan with the Kansas City Athletics in 1966. (Prince Edward Island Sports Hall of Fame)

The Halifax and District (H&D) Baseball League was a postwar offspring of the Second World War when Nova Scotia, and Halifax in particular, served as a major debarkation point for troops on overseas convoys assembled for the Battle of the Atlantic. During the war, many of Canada’s best ballplayers, some of whom, like Phil Marchildon and Joe Krakauskas, were major-league regulars, suited up with military clubs in the Halifax Defence League before departing for the “big game” overseas.

Swollen by the influx of soldiers and sailors looking for entertainment, crowds filled local parks around the region to watch the best local players compete against those from across the country. RCAF veteran Marchildon, who was later shot down and spent time in a German POW camp before returning to the majors after the war,1 was a member of an Air Force club that featured playing coach Art Upper, who had played in the Cape Breton Colliery League and with the International League Toronto Maple Leafs.

Their Air Force teammates included Windsor, Ontario, native Freddy Thomas, a multisport star and one of Canada’s best athletes in the first half of the century, and Manitoba native Les Edwards, who would contribute in many ways to baseball in Canada in the future.

Halifax Navy captured Provincial and Maritime honors in 1942 and 1943; HMCS Cornwallis captured the crown in 1944; and in 1945 the Springhill Fencebusters, one of the region’s finest town teams of the interwar years, defeated the best military clubs on their way to the Maritime title.

The H&D League opened play in 1946 as a four-team circuit made up of the Truro Bearcats, the Halifax Arrows,2 Halifax United Services, and Halifax Shipyards. In the league opener in Halifax, a crowd of 6,474 watched the United Servicemen edge the Shipyards 4-3, while Truro split a doubleheader against the Halifax Arrows.3

Although the Shipyards would continue as a powerhouse through the late 1940s, it was Truro’s Bearcats that were the class of the league (and of the region) in its inaugural season, led by young left-hander Philip “Skit” Ferguson from Reserve Mines, Cape Breton, and second baseman-outfielder Johnny Clark from Westville, Pictou County. Clark, Ferguson, and outfielder Buddy Condy led the parade of stars from the Maritimes in the early years, along with the Seaman brothers — Danny, Garneau, and Ike — who were fixtures with the Liverpool Larrupers for a number of seasons.

Danny Seaman had demonstrated his abilities during the war against Marchildon, collecting five hits in 12 at-bats and leading the big leaguer to comment that “Seaman hits the ball too hard and too often to be playing in Nova Scotia.”4 These players along with a number of other locals, veteran players from pro ball in the United States, and young college prospects from south of the border, joined together in a league that by the early 1950s was considered by many to be the most competitive unaffiliated summer league in Eastern North America.

There are three distinct periods in the history of the H&D League. The first of these was the period 1946-50, when the league completed a successful transition from military ball and maintained a healthy balance between local and imported players from the United States. At the time it was part of a network of similar semipro leagues operating elsewhere in the Maritimes, Maine, Quebec, and Vermont.

The second period spanned the years from 1951 through 1956, when the most competitive summer leagues in the east, including the Albemarle League in the Carolinas, the Blackstone Industrial League in the mill towns of Maryland, and the highly regarded Vermont-Northern League, all ceased operations, making the H&D League an especially attractive destination for American players from as far south as the Carolinas and as far west as the Great Lakes. (Although the Cape Cod League continued to operate at this time, it restricted itself to players from the Cape Cod region, and did not emerge as the leading summer collegiate league until the 1960s.)

The final period, 1957 through 1959, saw the H&D League shrink from a regular six-team operation with teams in Halifax, Dartmouth, Liverpool, Truro, Stellarton, and Kentville, to a four-team league made up largely of American college players considered prospects by major-league organizations.

Over its history the H&D League and others in the region graduated dozens of players to the majors, including Dick Gernert, Hal Smith, Charley Lau, Turk Farrell, Moe Drabowsky, Deacon Jones, Ron Perranoski, Al Spangler, Ty Cline, Dave Stenhouse, Rollie Sheldon, Maritime natives Billy Harris and Vern Handrahan, and many others.

THE EARLY YEARS: 1946-1950

With the transition from a wartime to peacetime economy, baseball in the Maritimes experienced a process of adjustment. As wartime athletes returned to their homes elsewhere in the country, or signed contracts within Organized Baseball, the H&D League and other similar circuits in the region such as the Central League, the Cape Breton Colliery League, various New Brunswick leagues, and the Maine New Brunswick League mixed local players and imported collegians and old pros from the United States.

Although there were a few American players on H&D League clubs when the H&D League began play in 1946, the import model took hold over the next couple of years as major-league organizations, especially the Red Sox, Dodgers, Giants, Yankees, and Boston Braves, began to send prospects still in school and veteran players and coaches to provide stability and leadership. Former New York Giant Crip Polli was given the coaching reins in Halifax.

A longtime minor leaguer in the Yankees system, Bob Decker, served as a Yankee scout and mentor with Dartmouth. Stuffy McInnis, a member of the Philadelphia Athletics’ famed “$100,000 Infield,” and then baseball coach at Harvard, looked after Red Sox interests with the Stellarton Albions in 1948 and 1949.5 And University of New Hampshire coaching legend Hank Swasey was at the helm in Kentville, presiding over Wildcats prospects like Art Ceccarelli, Dick Gernert, and 1949 Varsity Magazine college player of the year Jack Kaiser from St. John’s University. In 1950 virtually the entire St. John’s lineup was playing in the league alongside players from high-profile baseball programs in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania.

The Brooklyn Dodgers were especially active in those early years, sponsoring and supplying players for coach Oakie O’Connor in Edmunston, Ed Pesaresi’s Central League Amherst Ramblers, and the H&D League Wildcats. The Dodgers’ involvement in baseball in the Maritimes explains why the Brooklyn Junior Dodgers club included Halifax in its Brooklyn-Against-the-World Canadian swing in 1948.

Sponsored by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper to compete with the New York World’s Hearst Baseball Classic,6 the Junior Dodgers were led by future major leaguers Billy Loes, Don McMahon, and Joe Pignatano, and other prospects, many of whom ended up playing in the Maritimes. In addition to defeating all-star teams in Washington and Providence, the Baby Dodgers played three games north of the border. After defeating junior teams in Toronto and Montréal, they lost their only game in Halifax by a score of 3-1. Led on the mound by local boy John “Twit” Clarke, Halifax held the visitors to four hits.

Dodgers scouting director Mickey McConnell later told a Halifax columnist that he watched the defeat of the Dodgers with mixed feelings “since several of the players who put the lash on the Brooklyns were themselves members of the Brooklyn organization, and had been sent by him to the H&D League.”7 McConnell was particularly impressed with former 1947 Brooklyn star Herbie Rossman, who went 2-for-3 with a stolen base, and Saint John native Joe Breen, who along with a towering home run made two fine running catches in center field.

This was only one of a series of barnstorming tours that testified to the region’s growing reputation in American baseball circles. Beginning in 1948, the Birdie Tebbetts All-Stars became regular visitors to the region, bringing a cadre of major-league stars that included Jimmy Piersall, Phil Rizzuto, Johnny Pesky, Vern Stephens, Bobby Thomson, Al Rosen, Sal Maglie, and Mike Garcia, to name but a few. Tebbetts threw in the towel after the 1951 tour because of dwindling crowds, but a similar squad led by Spec Shea carried on in future years.

Other barnstorming clubs, among them the Georgia Chain Gang, the New England Hoboes, New York Equitable Life, the Boston Royal Giants, the Cambridge White Elephants, and the bewhiskered House of David also crisscrossed the region. For Haligonians, the three-game series between a combined squad from the Shipyards and Halifax Citadels against two-time US Amateur champion New York Equitable Life was particularly memorable. Local sportswriter Ace Foley’s memoir described “the greatest game ever played in my life. … It went into extra innings, the home team won … and it had everything including a triple play.”8

At the end of the decade, the import model was entrenched not only in the H&D League but everywhere in the region. Even small towns like MacAdam on the Maine-New Brunswick border — with 13 Americans on its 1949 roster — were looking south of the border for recruits.

There was still room for the better local players, however. In 1950, five of the top 10 qualifiers for the H&D League batting championship were home-brews, and outfielders Buddy Condy and Johnny Clark finished one-two in the batting race. Condy led the league with a .358 average in 260 at-bats, Clark followed at .350, and future major leaguer Zeke Bella finished fifth at .306.

Gradually, however, local players would increasingly be pushed aside as clubs turned over roster construction to American coaches and big-league scouts. “It was unfortunate,” Johnny Clark observed. “Gradually the average player in the league would be an import rather than local. We may not have been stars, but neither were many of those who came in and took our jobs.”9

In the decade to come, as the league expanded its geographical footprint southward and westward, only the best of the locals were able to crack H&D League lineups.

EXTENDING THE GEOGRAPHICAL FOOTPRINT: 1951-1956

From 1951 through 1956, the H&D League operated as a six-team circuit, with teams in Halifax, Dartmouth, Truro, Kentville, Liverpool, and Stellarton. At the same time, it extended its recruitment reach southward into the Carolinas and westward to the Great Lakes region.

The Carolinian connection began in earnest in 1951, when the Stellarton Albions assigned coaching and recruitment duties to Bill Brooks, a graduate of Wake Forest University and a four-year minor-league veteran catcher in the New York Giants organization. Brooks brought north the bulk of the Wake Forest Deacons lineup, including former All-American shortstop Art Hoch, father of PGA tour regular Scott Hoch, and 18-year-old infielder Gair Allie, Arnie Palmer’s college roommate and eventual starting shortstop of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1954.

Between them, Brooks and Hoch spent 13 summers in Nova Scotia, developing a pipeline of quality players from Southern colleges, especially Duke, UNC, North Carolina State, and Clemson. An NCAA finalist in the College World Series in 1949, Wake Forest represented the United States at the Pan-American Games in the spring of 1951, just a few weeks before heading north to play as the Albions during the summer.

In addition to its emerging Southern connection, the league continued to attract the top players from colleges in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania, and later with a number of schools in Michigan. In the four years beginning in 1952, three NCAA championship schools, Holy Cross (1952), the University of Michigan (1953), and Wake Forest (1955), sent their best players to the H&D League.

The same was true for tiny Elon College (1954), the smallest school ever to reach the College World Series finals. Fifteen of the players on the Holy Cross Crusader squad, for example, played in the league in the early ’50s. According to Crusader Don Prohovich, who played four years in the Maritimes, the H&D League was “the place to play for collegians in the 1950s,” and the league began to gain the reputation of being “NCAA North.”10

Prohovich played a number of years in the Chicago White Sox organization after that, topping out at the Triple-A level. It is not surprising that 15 first-team American College Coaches Association All-Americans, the equivalent of today’s first-round draft choices, ended up playing in the H&D League, as did a number of second-and third-team selections.11

In addition to the league’s Southern strategy, coach Ray Fisher of the 1953 NCAA Champion Michigan Wolverines began bringing players to the Maritimes in 1951 as the Vermont-Northern League teetered on the verge of collapse. Fisher coached for two years with the Black’s Harbour Brunswicks of the Southern New Brunswick League, bringing first team All-Americans Ken Tippery and Bruce Haynam along, then shifted to Truro of the H&D League in 1954.

The Maritime connection to collegiate baseball in Michigan, and with the highly regarded Detroit-Windsor Baseball Federation, had already begun a couple of years earlier, when a number of Windsor players with experience in the wartime Halifax Defence League returned to play with the Middleton Cardinals in the late ’40s. Windsorites Jimmy Dumeah, Gerry Davis, Bernie Parent, Paul Oleynik, Nick Nikita, William Symonds, and Chester Conn, and Michigan natives John and Jim Wingo, Al Ware, and Hal Smith arrived in 1949.

Another Windsor native, Maurice DeLoof, Midwestern regional scout for the Boston Red Sox and well known for signing future Red Sox Norm Zauchin, Ike Delock, and Dick “The Monster” Radatz, headed to Middleton in 1947 to join the pitching staff and keep tabs on H&D League prospects.

Although Stellarton won three successive championships in the early ’50s, led by Allie, Brooks, outfielder Joe Fulghum from Wake Forest, and first team All-American first baseman Billy Werber and catcher Leroy Sires from Duke, other teams in the league sported their own young prospects. Two of Werbers Duke teammates, Halifax’s Al Spangler, who went on to a 13-year major league career, and Dave Sime, Silver medalist in the 1960 Olympics 100-meter dash, spent two years in the region.

Elsewhere, Braves scout Jeff Jones was instrumental in assembling the Truro club every year, holding tryout camps in New England before the H&D League began its summer schedule. Often assisted by former Brooklyn Dodger Doc Gautreau, whose parents came from New Brunswick and Quebec, Jones signed dozens of players to Braves contracts, among them Prince Edward Island natives Vern Handrahan, who played parts of two seasons in the majors in the early 1960s, and Don MacLeod, another Charlottetown boy who played four years in the Braves organization, reaching as high as the Double-A Texas League.

In the mid-’50s an ill-conceived “bonus baby” regulation, requiring that signees with bonuses in excess of $4,000 be added to major-league 25-man rosters for two years, had an impact on the league. Because of the regulation, Tommy Gastall, who died tragically in a private plane crash in 1956, Tom Carroll, Art “Red” Swanson, Ralph Lumenti, and Moe Drabowsky all went to the majors directly from the H&D League, without a minor-league stop on the way.

Wild Bill Oster, who pitched for the Larrupers in 1953, and Angelo Dagres, who played two years in the New Brunswick-Maine league, also made the jump directly to the majors from the Maritimes. After winning the league batting title in 1955, Dagres was invited to a morning tryout with the Baltimore Orioles, who signed him immediately and inserted him in their starting lineup that same afternoon.12 This would simply not happen in today’s baseball environment.

PLAYING OUT THE STRING: 1957-1959

Despite its reputation for high-quality play, the league faced a number of challenges at the end of the 1950s. An economic slowdown, the coming of television, and the development of new patterns of leisure that accompanied widespread automobile ownership affected attendance across the Maritimes.

Already facing losses at the gate, Stellarton and Dartmouth began pushing for a restructuring of the league in 1955, calling unsuccessfully for salary caps and limits to the number of higher-salaried veteran pros that clubs could sign. All six teams operated through the 1956 season, but Halifax was close to folding that year before the Philadelphia Phillies came to their rescue with an affiliation agreement.13

Having lost their affiliate in Trois-Rivières when the Provincial League folded, and with manager Lew Krausse already signed to a guaranteed contract, the Phillies shifted their attention eastward. It was only a temporary fix, however. Halifax withdrew from the league in 1957, and Liverpool did as well.

The Phillies eventually worked out an affiliation with the Kentville Wildcats and eventually signed a number of players, including future big leaguers Norm Gigon and Lee Elia. Halifax returned to the league for the 1959 season with a team assembled by the Boston Red Sox and managed by career minor leaguer and eventual Washington Senators coach Joe Camacho.

In those final years the H&D League was a shadow of its former self. Although there were still a number of talented players on the field, the league had become a “prospects league” similar to short-season leagues within the Organized Baseball of the early twenty-first century.

Nova Scotia native Wilson Parsons, who played eight years in the Yankees organization, mostly at the Triple-A level, had the following remembrance of pitching for Dartmouth as a young flamethrower in 1951 and then again in 1959, when he relied on experience to get H&D Leaguers out:

“I think the talent in the H&D League in those early days was superior. You still had some individual stars in ’59, but I’m not sure that the depth was there like it was in ’51 or ’52. It just seemed so easy when I came back. I wasn’t trying to show anybody up. It was just what I had learned over the years…. I could hardly break a pane of glass, but there were so many different little things that I could do with the ball to set batters up.”14

Of the many young players in those waning years who would make their way to baseball’s higher echelons, the following players stood out. Ty Cline and Jack Kubiszyn ended up playing together with the Cleveland Indians in the early ’60s. Rollie Sheldon ended up pitching for the New York Yankees in the 1964 World Series. Clemson grad Hal Stowe also had a cup of coffee with New York.

Future Chicago Cubs Gordon Massa, Moe Morhardt, Don Eaddy, and Danny Murphy — .280 hitters in their stints in the Maritimes — were among a dozen or so players signed by former Cape Breton Colliery League star Lenny Merullo. Dale Willis, Jim Hannan, John Boozer, Jim Bailey, Bill Spanswick, Ed Connolly, and Ontario native Ken MacKenzie were among the many to end up in the big leagues.

Of all the prospects in the latter years of the H&D Leagues, none gained more attention than Danny Murphy. In the June 27, 1960, issue of Sports Illustrated, Roy Terrell gave a minute-by-minute review of the day the 17-year-old outfielder-pitcher Murphy was signed to a $100,000 bonus by Merullo.

Although he didn’t fulfill expectations as an outfielder, Murphy later turned into a solid major-league reliever with the Chicago White Sox.15 Another two-way player, Manly Johnson of the 1958 Kentville Wildcats, was a power-hitting outfielder and 20-game winner at Double A in the White Sox organization.

EPILOGUE

In a story in The Sporting News on June 30, 1962, one-time Yankee pitching ace Johnny Murphy, director of the Red Sox minor-league operations in the ’50s, spoke at length about the league’s demise. “When I was with Boston we were very much interested in the Nova Scotia league, a fast summer league that got most of the good high school and college boys,” said Murphy.

Conversations with various people in Nova Scotia suggested that the league needed about $10,000 per year in extra funding to continue operating. If spread out equally among all 16 major-league clubs, this would mean a minor outlay of about $600 per team, a pittance given how liberally bonus money was being spread around.

With this in mind, Murphy wrote “all fifteen other clubs telling them that this fine league could be kept going … [but] I got answers from only six clubs.”16 The result was the collapse of a 15-year experiment still remembered as a high point in the baseball history of the Maritimes.

DR. COLIN HOWELL (B.A., M.A. Dalhousie, PhD, Cincinnati) is professor emeritus in history, recently retired academic director of the Centre for the Study of Sport and Health at Saint Mary’s University, and a former co-editor of the Canadian Historical Review. He has published widely in the field of sport and health studies, and is the author of Northern Sandlots (1995), Blood, Sweat and Cheers: Sport and the Making of Modern Canada (2001), and a number of edited collections.

Notes

1 Phil Marchildon with Brian Kendall, Ace. Canada’s Pitching Sensation and Wartime Hero (Toronto: Viking, 1993), 111.

2 The Arrows would eventually move across the harbor to Dartmouth in 1949.

3 Burton Russell, Seven Decades of Nova Scotia Baseball. 1946-2016 (Kentville: Self-published, 2017), 7.

4 Quoted in Burton Russell, Nova Scotia Baseball Heroics (Kentville: Self-published, 1993), 38.

5 The Sporting News, December 1,1948 (page 17) reported on Mclnnis’s summer in Nova Scotia. “I don’t believe I ever had any better time in my life,” said Mclnnis. “Those coal mining people were crazy about the game and the players, most of whom were boys who worked in the mine all day. But tired and all and with little previous experience, they did well enough to battle Halifax for the championship.” Mclnnis returned to coach in 1949 as well.

6 Alan Cohen is the acknowledged expert on the Hearst Classic. See his “Baseball Stories” at https://alancohenbaseball.wordpress.com.

7 Halifax Chronicle Herald, August 4, 1948: 6.

8 Ace Foley, The First Fifty Years. The Life and Times of a Sportswriter (Windsor, Nova Scotia: Lancelot Press, 1970), 24-25.

9 Personal interview with Johnny Clark, Halifax, November 29, 1989.

10 Telephone interview with Don Prohovich, June 16, 1994.

11 American Baseball Coaches Association First Team All-Americans to play in the Maritimes: Bill Werber Jr. (Duke), 1952; Jim O’Neill (Holy Cross), 1952; Fred Flemming (Bowdoin), 1953; Bruce Haynam (Michigan), 1953; Charles Heerlein (St. John’s), 1954; Linwood Holt (Wake Forest), 1955; Don Prohovich (Holy Cross), 1956; Marsh McLean (Amherst), 1957; Ken Tippery (Michigan), 1957; Frank Saia (Harvard), 1958; Bob Wedin (Connecticut), 1958; Moe Morhardt (Connecticut), 1958; and Ty Cline (Clemson), 1960.

12 Author interview with Johnny Clark, Halifax, November 29, 1989.

13 Author telephone interview with Don Provohich, June 16, 1994.

14 Author interview with Wilson Parsons, Truro, Nova Scotia, September 1, 1995.

15 Roy Terrell, “The Signing of Danny Murphy,” Sports Illustrated, June 27, 1960: 32-37.

16 The Sporting News, June 30, 1962: 4.