The Hall of Fame Looks at Baseball Scouts

This article was written by John Odell

This article was published in Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (2011)

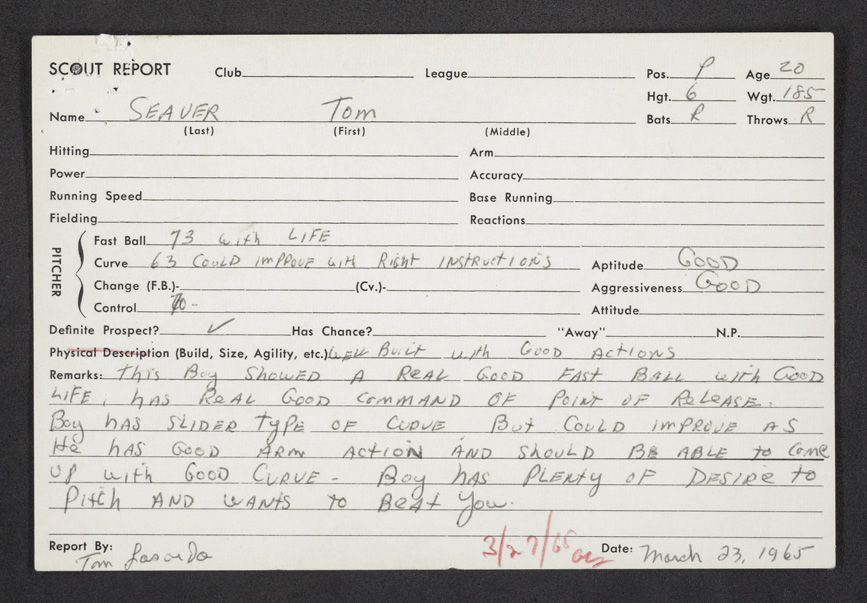

Tom Seaver scouting report, 1965. (Click to enlarge.)

Just as an iceberg reveals only a small part of its mass, the public face of baseball shows only a fraction of the work required to assemble clubs and stage games. The nonplayer personnel are, in many ways, the unsung heroes of the game.

For years, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum has gone beyond the essentials of bats, balls, and gloves to collect the tools used by those engaged in the other, unseen aspects of the game. Photographers, writers, grounds crew, and scouts are all a part of this hidden game, and their cameras, typewriters, and field equipment have been duly added to the Hall’s collections.

Among this group, the scouts’ contributions are unusual, as their work regularly takes place away from their own ballparks. Traveling throughout an assigned territory, scouts scour the sandlot, high school, or (increasingly) college fields to find a gem, preferably one undiscovered by their competitors. The title given them by The Sporting News, “ivory hunters,” suggests their travels through the wilds of the Americas to find their rare quarry—the elusive major-league prospect. Aside from interstates and air conditioning, the scout’s job has changed very little since the era of such legendary figures as Paul Krichell and Cy Slapnicka.

The scout’s tools are relatively simple: a stopwatch, notebook, and pen, a hat for the sun and, more recently, a radar gun. In addition to these items, the Hall of Fame has also collected examples of the most tangible things scouts create: their scouting reports.

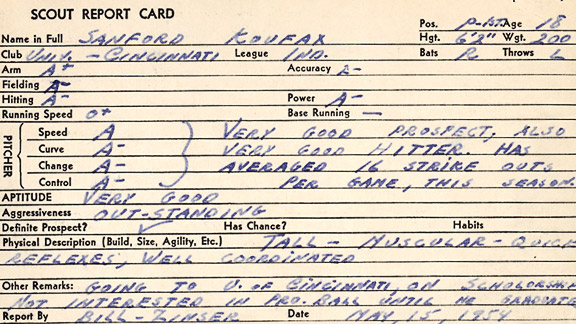

Our desire to build a much larger collection of scouting reports comes from several perspectives. First, as a research institution, the Hall is interested in all aspects of baseball, from the game on the field, to its cultural ties, to the game off the field. While we hold over two million documents in our archives, the amount relating to this important area of the game is seriously underrepresented. Over the years, a handful of reports have trickled in, mostly for Hall of Famers like Sandy Koufax, Tom Seaver, and Roberto Clemente. These reports excited us, and the more we considered them, the more we thought these documents might be exciting to our visitors. We began to develop a plan to collect and share as many reports as we could in an interactive database.

As we began a search for more reports, we started calling and interviewing many scouts, active and retired, throughout the country. In pursuing these reports, we discovered they were elusive for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, perhaps, free-agent scouting reports embody the very essence of ephemera. While multiple teams may research and pursue a prospect, only one can sign him. Once signed, the player is a professional ballplayer, and moves into the smaller, somewhat more structured scouting universe surrounding the minor leagues. At that point, the free-agent scout’s professional interest in the player diminishes markedly, and his old reports, now largely irrelevant, are often disposed of.

Another difficulty in obtaining the reports involves ownership. Regardless of who has a copy, the reports themselves belong to the scout’s employer, the big-league team. Without the team’s approval, a scout cannot transfer the documents to someone else. Most teams, moreover, are focused on the future. They do not have the time or inclination to perform a cost/benefit analysis to decide whether to allow their scouts to release information. So, largely by inertia, the default answer to a scout seeking permission to donate reports is often, no.

When asked to consider donating their reports, scouts voiced another concern. This was tied to the brutal honesty a report entails–how good is a player, and how much should he cost? No one has to tell scouts that they miss more often than they hit, and these reports graphically illustrate the uncertainty that lies at the heart of the profession. The reports document all of a scout’s failures in the unvarnished language the profession demands. The result is almost a prescription for an unflattering portrayal of both the player in question and the scout’s assessment.

The final hitch in the acquisition of reports stems from the core of a scout’s job. By necessity, the scout’s business is one that combines secrecy and personal responsibility. The names, locations, abilities, and projections of a scout’s prospects are closely guarded during the chase. Giving those data to an institution that is devoted to sharing information with the world is a difficult leap to make. While scouts see themselves as one of the least understood professions within the game, sharing such a personal part of their work does not always come naturally.

Sandy Koufax scouting report, 1954. (Click to enlarge.)

Fortunately, with the help of many scouts and baseball executives, we have been successful in starting the construction of that database. Over the past decade, we have acquired over 2,000 scouting reports on more than 1,000 players, compiled by about 200 scouts. These are largely within our primary focus of free-agent or amateur scouting, the segment of the profession that beats the bushes to bring new talent to the game. In addition, we have received a few reports for professional players, sometimes from the minors, but also created in preparation for the postseason.

These documents run the gamut in terms of the information they contain. Some are wonderfully detailed, outlining the scout’s impression of the baseball player. Most often, the reports contain only a single word that notes the scout’s interest: “Follow.”

One distinguishing characteristic of the reports is the scouts’ continuing use of the term “boy” to characterize all their prospects. Upon first reading, it seems pejorative in some way, since we now know the majority of these “boys” as men. After reflection, the word serves as a reminder that the players a scout seeks are, in fact, boys, 15, or 16, or 17 years old, and young enough to be many scouts’ grandsons.

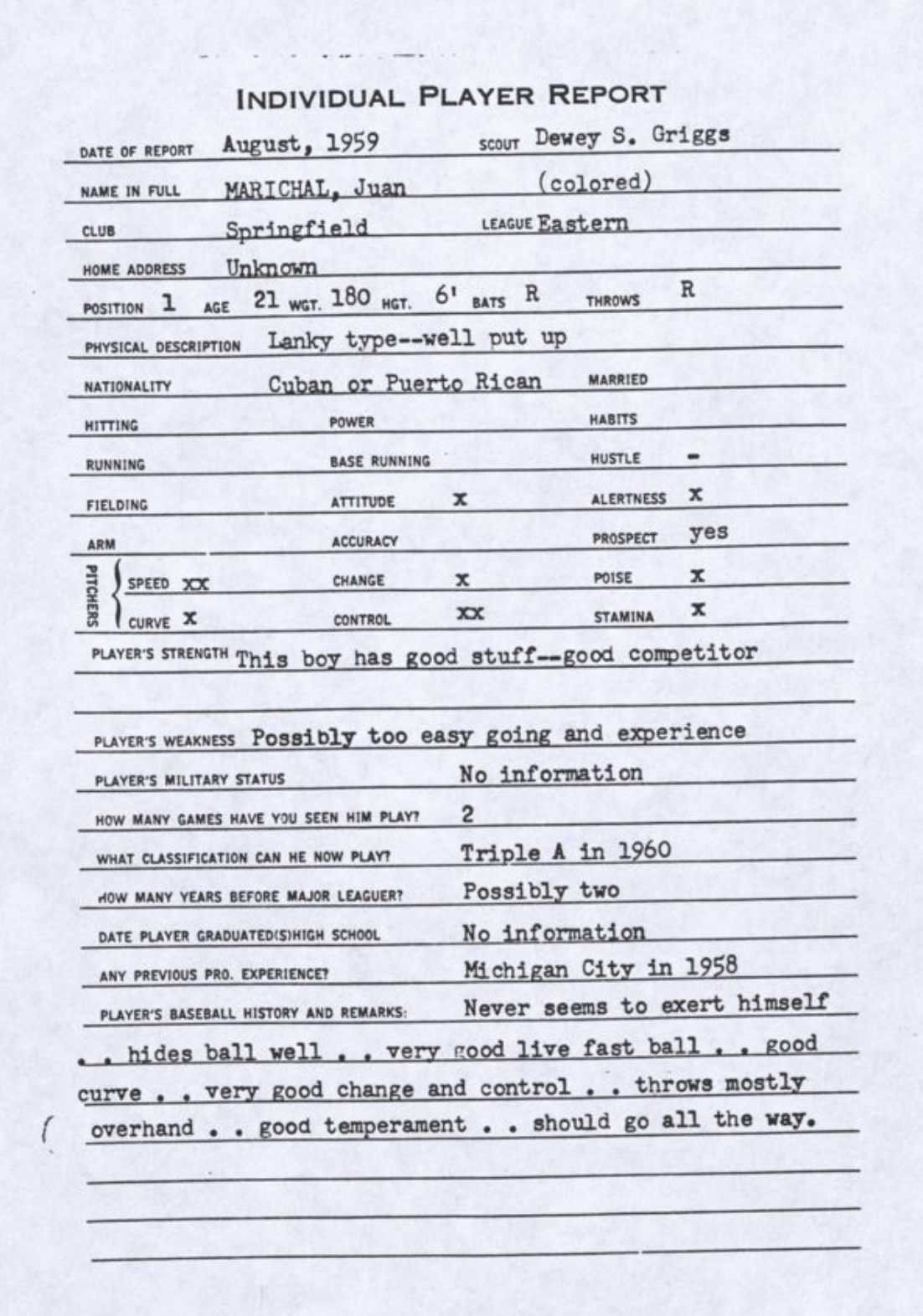

On older reports, the racial issues our nation has long wrestled with are reflected in the language used. If a white player was known simply as “boy,” his African-American counterpart was often jarringly referred to as a “Negro boy” or “colored boy.” At a time when job and loan applications outside of baseball demanded to know one’s race, teams felt they also needed to know a prospect’s race as much as they needed to know his speed to first.

Mostly, though, the thrill of these reports is seeing the dead-on assessment of a scout’s prospects. Scout Dewey Griggs summed up young Juan Marichal by noting the trait that drove opposing batters to exasperation, “Never seems to exert himself,” before concluding, “very good live fast ball…should go all the way.” After rating 18-year-old Roberto Clemente A or A+ in arm strength, fielding, hitting, accuracy, reactions, power, and base running, scout Al Campanis elaborated: “Has all the tools and likes to play…Will mature into big man.”

Finally, said scout Tommy Lasorda of Tom Seaver, a sophomore at the University of Southern California, “Boy has plenty of desire to pitch and wants to beat you.”

An exhibit on scouting is on the long-term agenda of the Hall, and when it opens, we look forward to bringing these and other reports to our visitors. In the meantime, they are available by advance reservation to researchers at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, here at the Hall of Fame.

JOHN ODELL, curator of history and research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, rejoices daily that he can merge his lifelong passion for baseball with his museum vocation. He resides in Cooperstown, New York, with his wife, Peg, and their three children. A Virginia native, Odell is an Orioles fan but loves seeing any baseball game, at any level, so long as it is live and in person.

Photo credits

All images courtesy of National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Juan Marichal scouting report, 1959. (Click to enlarge.)