The Hammer Hits the Road: A New Look at Henry Aaron’s Home Run Record

This article was written by Eric Marshall White

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

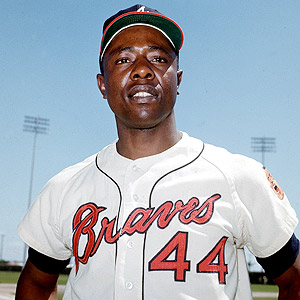

“Although he never hit more than 47 home runs in a season…” was a common refrain in the eulogies that marked Henry Aaron’s passing on January 22, 2021.

Intended as a nod to Aaron’s workmanlike virtue, the suggestion that his peak fell short of the more spectacular feats of other sluggers set up the inevitable pivot to the main point, that his 23-year climb to the top of the all-time home run list highlighted two even greater virtues: superlative consistency and longevity.1 Developed over several decades, the popular image of “Quiet Henry” wielding his relentless hammer underpins our understanding of Aaron’s legacy within baseball history and American folklore.2

The underlying facts are not in question: Aaron’s career did exemplify longevity; his performance was remarkably consistent; his best seasonal home run total (47 in 1971) did not threaten any records; and of course he did later eclipse Babe Ruth’s career record for home runs. Nevertheless, the common wisdom regarding Aaron is misleading. It is framed so that the titanic breadth of his career-long achievement must provide necessary compensation for the supposedly low ceiling under which he performed. Thus, Aaron’s career is remembered as a somewhat quiet, deceptively plodding marathon that lacked the flashy brilliance of more supercharged careers.3

In fact, the notion that Aaron did not have what it takes to hit 50 or more home runs in a season understates his true greatness, because it bows unnecessarily to the inflated feats of less-worthy competitors against whom his peak ability has been compared unfavorably. A fresh examination of overlooked but essential evidence, considered in proper context, reveals that the common wisdom falls prey to statistical illusions and analytical pitfalls that have distorted our perceptions of Aaron’s unique strengths and have misdirected our assessments of his career.

“ONLY 47” HOME RUNS

Following decades of rampant home run proliferation, it became possible for the compiler of Aaron’s obituary in The New York Times to remark that the Hall-of-Famer’s “highest total was only 47, in 1971.”4 It should go without saying that 47 is historically an impressive number of home runs for a single season: People do not complain that Lou Gehrig hit “only” 47 home runs in his legendary 1927 campaign.

The fact that Aaron never surpassed 47 home runs should not be particularly remarkable or disquieting: other famous sluggers who failed to exceed the same threshold include Reggie Jackson (47), Ernie Banks (47), Eddie Mathews (47), Joe DiMaggio (46), Willie McCovey (45), Johnny Bench (45), Carl Yastrzemski (44), Ted Williams (43), Duke Snider (43), Mel Ott (42), Rogers Hornsby (42), and Stan Musial (39).

During Aaron’s lengthy career, from 1954 to 1976, only eight players managed to exceed 47 home runs in one year, although they did it on thirteen occasions.5 However, eight of those performances tacked on a mere homer or two, and even though Roger Maris once managed to exceed Aaron’s top mark by 14 home runs, that did not put him significantly closer to Ruth’s career mark.

There are multiple problems with the suggestion that Aaron’s failure to exceed 47 home runs in a season made him a long shot to challenge Ruth’s home run record. First, a single-season high-water mark does not define a player’s greatness. If it did, then Maris would already be in the Hall of Fame while Aaron, with his peak of “only” 47 home runs, might still be just another popular underdog candidate.

A single season is an extremely limited sample. One can remove any one of seventeen different Aaron seasons and he still would have 715 or more home runs. Strong decades matter more than epic seasons. Most career records for counting statistics, even Babe Ruth’s, have required about twenty years of high-rate accumulation. There is nothing especially insightful about the idea that Aaron needed longevity to break an all-time record when that is a given for anyone. Aaron’s excellent rate put him over the top. His totals for two or three seasons were excellent; his totals for four, five, and six or more seasons were prodigious.

Before Aaron’s retirement, only Ruth, Foxx, Killebrew, Gehrig, and Mays had hit more home runs in any ten-year run, and only Ruth exceeded Aaron’s since-broken National League record of 573 home runs in fifteen seasons. Clearly, the traditional unit of the single season is not the best indicator of Aaron’s ability to hit quantities of home runs quickly, and the common wisdom has made too much of the perception that Aaron’s ability to compile home runs in a given year was relatively modest.

A second point to consider is that 1971 was not really Aaron’s most impressive home run season. That year, he hit 16 home runs on the road to go with 31 in Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium, where the ball carried well because the field was 1,050 feet above sea level. It was an amazing accomplishment for a 37-year-old in 495 at bats—compare Ernie Banks, who won an MVP award in 1958 with 30 home runs at Wrigley Field and 17 on the road over 617 at bats—but Aaron had several better years. In three campaigns during which he connected for 44 or 45 round-trippers (1957, 1962, and 1963), his home numbers were held down by difficult hitting conditions, including chilly weather, in Milwaukee’s County Stadium. But he blasted 26, 27, and 25 road home runs in those seasons (with 83 road RBIs in 1957!), leading the league each year.

Aaron also had a pair of 44-homer seasons during his tenure in Atlanta in which he twice hit 23 on the road, finishing second to Donn Clendenon’s amazing total of 25 in 1966 and pacing the league for the fourth time in 1969. Moreover, he connected for 20 home runs in his road games during the 1958 pennant-winning season, hit 19 in both 1959 and 1960, and collected 15 or more in six other seasons. These were Ruthian feats in any context and in any era.

One might even argue that Aaron’s seasonal home run rate was a more important component of his assault on Ruth’s record than his longevity was.6 Plenty of players have played for twenty or more seasons, but only three (Aaron, Ruth, and Barry Bonds) have averaged 35 home runs over two decades. Mays played 22 seasons but came up well short of this pace. Aaron played 23 seasons, but he needed only twenty seasons plus three games to break Ruth’s record. His home run pace, seen in proper context, was by no means a modest one. It was historic.

A TALE OF TWO CITIES

As Bill James pointed out in his Historical Baseball Abstract (1986), some of the tranquil consistency in Aaron’s home run ledger is a statistical illusion caused by park effects: “At his peak, Aaron would have hit 50 home runs, and probably more than once, had he been playing in an average home run park.” Aaron considered Milwaukee’s County Stadium a “fair” (meaning symmetrical) ballpark where he could “see the ball well,” but it played large, meaning it tended to contain long drives that were home runs elsewhere, resulting in 185 home runs from Aaron’s bat in Milwaukee versus 213 on the road during his first twelve seasons (1954–65).7

Whereas Aaron was held to four 40-homer campaigns in Milwaukee between ages 20 and 31, Atlanta’s “Launching Pad” boosted his gradually waning power production during his later years (1966–74), giving life to one or more of the four 40-homer campaigns that he enjoyed between ages 32 and 40. Naturally, a ballpark cannot cause baseballs to exit all by themselves—Aaron still had to hit hundreds of balls high and far and fair in Atlanta—but in the hope of taking full advantage of the thin air he began to lay off outside pitches more and adjusted his swing for greater pull and loft, doing so far more effectively than any of his rivals did.

Henry Aaron found the home-run-hitting conditions in Atlanta more favorable than in Milwaukee. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

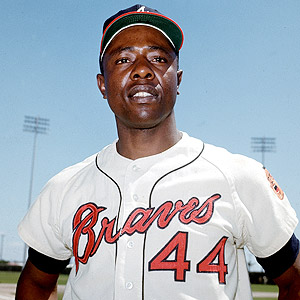

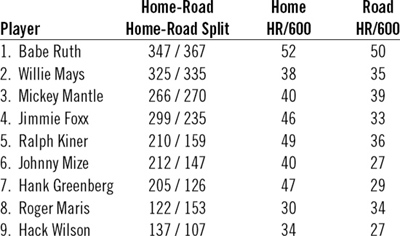

Park-neutral performance is more indicative of home run-hitting ability than simply asking whether a player was able to hit more than 47 in a season.8 Therefore, it is significant that at the time of his retirement, Aaron had compiled six seasons with at least 20 home runs on the road, the second-most in baseball history (tied with Mays and Killebrew). Ruth, as usual, was in a league of his own with 13 such seasons; Schmidt later reached seven. Listed below are all the players active before or during Aaron’s career (that is, by 1976) who accumulated at least 100 home runs in road games during their five best seasons in that category; for purposes of ranking, ties are broken by career road home run totals (Table 1).

Table 1. Hitters (1900–76) with 100+ Road Home Runs in Their Five Best Seasons

(Click image to enlarge)

In this contest of park-neutral skill, Aaron is not just a steady also-ran, to be found near the bottom of this fast company, nor is he in the middle of the pack. The guy who never hit more than 47 home runs in a season is up there at the top of the list, behind only Ruth. Indeed, he leads all competitors from baseball’s post-integration, pre-steroid era. Who knew?

Even when the five-year durability criterion is eased back to a player’s top four seasons, which favors not the tortoise but the hare, this presents no problem for Aaron, who holds onto third place (101 road home runs), just one behind the surprisingly lethal Mathews (102), and just two home runs per year short of The Babe’s best efforts (109). Conversely, as we increase the number of sample seasons to six and beyond, Aaron pulls away from the pack and eventually surpasses even Ruth, ending with 370 lifetime road home runs.

While Aaron’s lofty ranking may be surprising, it is a testament to his top-tier proficiency on the road that he was able to climb to the very precipice of the all-time record in his twentieth season. For two decades he had been greater than recognized, and his numbers, seen in proper context, were better than all but Ruth’s.

AARON IN COMPARISON TO THE 50-HOMER CLUB

At the time of Aaron’s retirement in 1976, only eight players besides Babe Ruth had ever hit 50 home runs in a single season. According to those who perceived Aaron’s peak of 47 home runs to be a relatively modest total, it was these eight men—or men very much like them—who should have been the likeliest candidates to break Ruth’s lifetime record for home runs. Two of them, Mays and Mantle, reached the big leagues at young ages, twice hit 50+home runs, and lasted long enough to become legitimate threats to Ruth’s record before falling off the pace. (Their road performances will be discussed in greater detail below.)

Henry Aaron entering 1973 having surpassed Willie Mays in career home runs. Synchronized by age, Hank had always been ahead of Willie’s road home run pace. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

However, the six remaining members of the club were never realistic record challengers. Whereas Ruth, Mays, and Mantle (like Aaron) performed within the normal expectations for home-park leniency, the rest of the 50-home run club, with one notable exception, was essentially the product of drastic home-park advantages. Here are their home-road splits and their rates of home and road home runs per 600 at bats (Table 2).

Table 2. The 50-Homer Club through 1976: Home/Road Splits

Jimmie Foxx played in twenty campaigns but did most of his damage (503 home runs) in the thirteen seasons from 1929 to 1941. He took tremendous advantage of Shibe Park and Fenway Park, compiling home-road splits of 31/27 in 1932, 31/17 in 1933, and 35/15 in 1938. His 235 road home runs are a more accurate measure of his muscles than the 299 that he hit in friendly ballparks.

Even with his enormous home-field advantage, Foxx was no match for Aaron, who outpaced him with 533 home runs across fourteen seasons and pulled away with nine more productive campaigns. Although The Beast’s 58 home runs in 1932 dwarfed Aaron’s 47 in 1971, his road totals are far less impressive, and the nine-homer difference in their pinnacle seasons ultimately had little impact on the final tally, which Aaron won by a margin of 221 home runs.

Ralph Kiner took enormous advantage of Kiner’s Korner at Forbes Field, with peak years of 51 home runs in 1947 and 54 in 1949, featuring home-road splits of 28/23 and 29/25. Overall, he collected 369 home runs in a career that lasted ten seasons. But this pales in comparison to Aaron, who never topped 47 home runs in a season, but who could choose from eight different ten-season spans in which he hit 370 or more home runs, topped off with a total of 386 round-trippers from 1962 to 1971. Thus, we may ask, why should Kiner-esque totals of 54 or 51 home runs be considered such a big deal when Aaron was so quick to make up the difference, and more?

Johnny Mize, Hank Greenberg, and Hack Wilson entered the 50-homer club with performances that were boosted significantly by accommodating home parks: Mize clobbered 51 home runs in 1947, with 29 at the short-cornered Polo Grounds and a personal-best 22 on the road; Greenberg chased Ruth with 58 home runs in 1938, smashing a record 39 at cozy Briggs Stadium in Detroit and a career-high 19 on the road; and Hack Wilson hit 56 home runs in 1930, with 33 leaving the friendly confines of Wrigley Field and 23 on the road, by far his top total.9

Their career-best road totals would have represented good seasons for Aaron, but nothing out of the ordinary. The fact that Aaron repeatedly outperformed Foxx, Kiner, Mize, Greenberg, and Wilson on the road reveals that he was truly a greater power threat than these 50-homer legends ever were, and it destroys the common wisdom that Aaron needed unusual longevity and a late boost from a friendly home park to compensate for a lack of transcendent brilliance.

As a side note, the great exception among the early 50-homer club members was the lone non-Hall of Famer, Roger Maris, another home run record-setter who became a victim of taunts and under-appreciation. Unlike the other eight, he alone managed to hit more home runs on the road than at home in his biggest season, 1961 (30/31). He also did it in his second-best season, 1960 (13/26), the summer before expansion, as well as by a wide margin across his injury-shortened career (122/153). The two-time Most Valuable Player was never a candidate to set any lifetime marks, but he was by no means a one-year wonder, just as he was not simply a home-park phenom. Unbeknownst to many except those reading this article, Maris still holds the all-time record for most home runs hit during consecutive pennant-winning seasons: 182.

KING OF THE ROAD

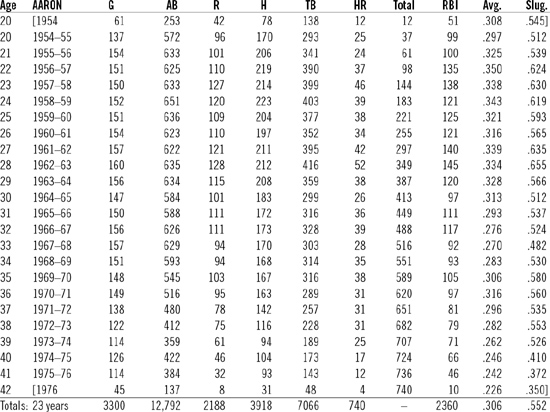

Aaron retired as the all-time leader in home runs hit on the road. Recognizing the importance of park-neutral performance, Bill James combined Aaron’s road home run totals from consecutive seasons into two halves of a single road “season,” creating a relentless career-long road trip in which the slugger produced an outstanding rookie campaign with 25 home runs, highs of 52, 46, and 42 home runs during the Milwaukee years, and highs of 39, 38, and 35 during the Atlanta years, even while never being able to enjoy the advantages of home cooking, lengthy stays, or friendly fans.

Although James’s method is artificial (requiring repetition of the first and last single seasons) it illustrates the main point: canceling out the disparate influences of Aaron’s home parks, the road totals indicate a more natural career arc, with a true peak at age 28 in 1962 and with no notable spike at age 37 in 1971. The chart below recreates the James experiment and fills out some of Aaron’s amazingly productive road statistics (Table 3).

Table 3. Consecutive-Season Road Numbers Combined into Single-Season Approximations

(Click image to enlarge)

In this light, it may be more meaningful to remember Aaron for the 52 home runs that he hit on the road at age 28 than for the 47 he actually hit while playing his home games in Atlanta at age 37. The only better consecutive-season home run performances on the road were by Ruth (1927–28) and Maris (1960–61), with 57 each; Ruth again (1926–27) with 56; Mathews (1953–54) with 54; and Jim Gentile (1961–62) with 53.11 Matching Aaron’s high of 52 were Ruth (1920–21) and Mike Schmidt (1979-80). Next came Mays with his twin peaks of 50, Ruth (1928–29) with 50; Gehrig (1930–31) with 49, Ruth yet again (1921–22 and 1929–30) with two instances of 48, and Joe DiMaggio (1936–37) with 48 in his rookie and sophomore road trips.

Meanwhile, some very big names, including six players who hit 50 home runs in normal seasons, are missing from this company. While George Foster hit 47 road home runs in 1976–77, edging Aaron’s second-best effort (46) from 1957–58, Kiner topped out at 45 in 1949–50; Foxx at 44 in 1932–33; Mize at 37 in 1947–48; Wilson at 37 in 1929–30; and Greenberg at 36 in 1938-39.

Road totals indicate that Hammerin’ Hank Aaron, with his peak totals of 52 in 1962–63 and 46 in 1957–58, was genuinely more productive on a seasonal scale than these legends were.

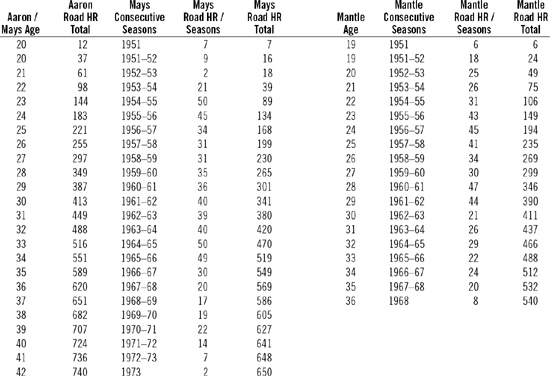

For career-long comparisons, the same consecutive-season road home run chart can be compiled for Mays, Mantle, and others. Remarkably, both Aaron and Mays averaged one home run every 17 at bats on the road, so here Aaron’s longevity took the prize.12 Mays also had a slower start, caused by time away during the the Korean War. If Aaron, not Mays, had lost most of two prime years to military service, then Mays might have been the second man to reach 700 home runs.13 Once back, Mays quickly reached a peak of 50 road home runs in 1954–55, fell back to the low 30s for a spell, then surged to 50 again in 1964–65.

Aaron, meanwhile, reached a loftier pinnacle (52), won 17 of their head-to-head races, enjoyed more 30+ home run seasons, and did not fade as quickly. Memories of Aaron sneaking up on Mays in pursuit of various offensive milestones in the early 1970s helped lock in the notion that Aaron’s success came from a strong late push. Make note, however, that when their road home run performances are synchronized by age, Mays was never ahead of Aaron’s pace (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparing Aaron, Mays, and Mantle: Consecutive-Season Home Runs, by Age

(Click image to enlarge)

Switch-hitting Mickey Mantle was park-proof, wielding enough power to propel the ball out of any arena in any direction. Yankee Stadium’s “Death Valley” in left-center may have cost him a home run or two per year, but most of his at bats took aim at right field, where there was a short porch. Away from Yankee Stadium, Mantle hit 185 home runs batting lefty and only 85 righty, but with rates of one home run per 15 at bats each way.14

Compared to Aaron, Mantle had seven fewer combined road seasons with 30+ home runs, peaked with “only” 47 home runs (1960–61), had his last great season at age 29, and finished with a road total of 540 home runs—200 behind a road warrior who never set foot in Atlanta. Whereas Mantle started ahead of Aaron’s pace by making his debut at 19, Aaron’s closure of the gap was relentless. He pulled ahead of Mantle during their epic age-28 seasons (52 vs. 47) and passed him for good at age 30 (Mays finally passed Mantle when they were both 34).

Other famous sluggers, including Gehrig, Foxx, Banks, Killebrew, McCovey, Jackson, and Schmidt, were never able to match Aaron’s pace, early or late. Mel Ott started fast as a teenager but was not the same level of threat on the road. Both Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams went ahead at early ages, but already by 1940 Joe was falling behind the pace Aaron would set (further proof of Aaron’s amazing start).15 Ted lost his lead when he gave up his 1943 season to military service.16 Even if Joe and Ted had remained in the lineup during the war years, matching Aaron’s combined road home run totals at the same ages would have been a very tall order. Either way, they eventually would have fallen short of both Ruth and Aaron.

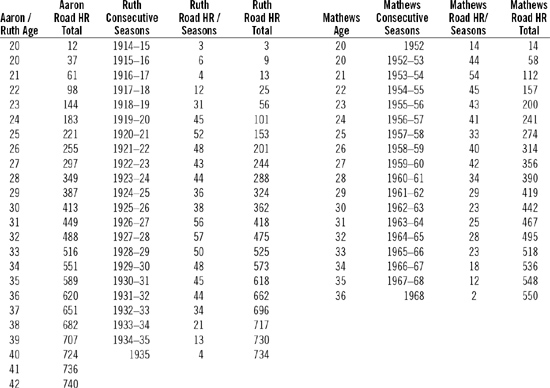

Aaron’s greatest challengers are actually Ruth and Mathews. Ruth began his career as a pitcher before converting to being a full-time power hitter, and thus in our game of age-synchronized longball, Aaron will have already hit more than 500 home runs before Ruth catches him at age 33. The Babe will pull as many as 45 road home runs ahead, but then fall half-a-dozen short after his retirement.

Mathews took the opposite approach, getting off to the fastest start of the century and holding off Aaron’s assault until their age-31 seasons. Aaron’s good friend and Milwaukee teammate paced his league in road home runs (in actual seasons) four times, with a high of 30 in 1953, but tailed off during the pitching-dominated Sixties. In some ways the third baseman’s consecutive-season road performance is more impressive than Mantle’s. Canceling out eight seasons in which they compiled equal home run totals, Mathews still had seasons of 54, 42, 40 and 33 to compare to Mantle’s 47, 31, 30, and 26, and he ended up with 10 home runs to spare, although Mantle edged him slightly on power rates (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparing Aaron, Ruth, and Mathews: Consecutive-Season Home Runs, by Age

(Click image to enlarge)

WHO WERE THE GREATEST HOME RUN HITTERS?

It would seem perfectly easy to state outright that Babe Ruth was the greatest slugger in baseball history, based on his eye-popping home-run hitting feats at home, on the road, during his peak, and across his career. Some may argue that the racially segregated competition that Ruth faced, and the less challenging conditions under which he played, argue against his top standing. While it seems plausible that paunchy, libertine Ruth, transported through time, might have kept pace with Williams, Musial, and DiMaggio during the 1940s if he could hit at night, it becomes even harder for many to picture him competing at the same level against Mays, Mantle, and Aaron in subsequent decades, facing fresh-armed relief specialists after coast-to-coast travel. Others may dismiss these doubts.

No one is dismissing The Babe’s abilities in his own time, but it is no less reasonable to question how his numbers would hold up under the greater competitive pressures of later eras than it is to insist on their eternally unchallengeable superiority.

Here one must also consider Josh Gibson (1911–47), whose plaque in Cooperstown asserts that he “hit almost 800 home runs in [Negro] league and independent baseball.” Even if this could be documented, the moundsmen he faced across those endless summers ranged in quality from certified immortals to local volunteers. Given that Gibson was hitting titanic home runs at Yankee Stadium by age 19 but died of a stroke at age 35, one must accept that even a player of his conspicuous talent could have spent no more than 17 seasons in the retroactively integrated major leagues.

As history has shown, it is difficult enough to average 35 home runs per year across twenty years in order to reach 700, as Ruth and Aaron did; the argument that Gibson, a catcher by trade, would have maintained the even higher rate necessary to reach the same plateau in seventeen seasons (17 seasons × 42 home runs=714 total) enters the realm of hypotheticals and wishful thinking.

Many exclude Barry Bonds from consideration because they believe his natural skills fell short. From 1986 to 1998, over the course of 1,898 games, Bonds tallied 411 home runs, establishing firmly (through age 34) that he had the ability to hit as many as 46 home runs in a season while leading his league only once and averaging 32 per season. Aaron, reaching age 34 in the “Year of the Pitcher,” already had hit 510 home runs while pacing his league four times and averaging 34 per season.

To that point Bonds’s home run ability looked superficially like that of Reggie Jackson or Willie McCovey, although in historical context it was more like that of Eddie Murray or Andre Dawson, who each likewise led in home runs once, albeit during an era that was far friendlier to pitchers. Then, in the seasons in which he turned 35, 36 and 37, Bonds showed a startling upswing in power: he smashed 34 home runs in only 355 at bats in 1999; reached a new career high with 49 in 480 at bats in 2000; and then more than doubled what had been his career home run percentage per plate appearance (5.4%) with 73 in only 476 at bats (11%) in 2001, the first of four straight MVP seasons.

Understandably, it is widely suspected that Bonds’s late-career power increase resulted from the use of performance-enhancing drugs. If so, his record belongs to a different category of evidence that is not directly comparable to Aaron’s.

Henry Aaron was a supremely well-qualified candidate to break Ruth’s career home run record from the day he reached the major leagues. He started fast at a very young age, upped his game as he realized the value of his power swing in the late Fifties, surged even higher at his physical peak around age 28, made the most of a golden opportunity in Atlanta, and worked hard to take care of himself as he aged.17 To repeat the point, the “Launching Pad” did not transform Aaron into something he was not meant to be. Atlanta’s thinner air merely gave him back the home runs that he had lost in Milwaukee—plus umpteen more spread over nine seasons there—so that he was able to speed past Ruth’s record in April 1974 instead of in August 1974.

The fact that Aaron succeeded where all others had failed attests to his unique ability, adaptability, determination, and courage in the face of multiple death threats from racists. Although biased or uninformed members of the press and public during the early 1970s dismissed him as an unworthy interloper within Ruth’s mythic realm, in truth they could easily have questioned the legitimacy of the legendary records of Ruth, Cy Young, Ty Cobb, and others that were set under conditions of competitive imbalance and social injustice. The standard Aaron set in 1974, although since broken, ranked among the most worthy and legitimate of all of baseball’s major records.

CONCLUSION

No single season can define Henry Aaron’s greatness as a home run hitter. The sustained dominance that he demonstrated as a home run hitter in neutral parks was second only to Babe Ruth’s in the pre-steroid game, and it was unsurpassed during the integrated era in which he played. Ruth and Aaron were genuine 700+ home run talents, combining innate longevity, raw power, and peak ability like no one else.

Mays and Williams came the closest to joining this rare company. Gibson passed from the earth far too early, and even the mighty Mantle could not keep pace. Neither could later stars like Albert Pujols, Ken Griffey Jr., and Jim Thome, not to mention the allegedly substance-enhanced sluggers of recent memory. Aaron thus emerges (again) as a true home run king: he was able to hit great quantities of home runs regardless of the ballpark, and he set a high bar for production that few could match in the short run, and none (save for Bonds) could match in the long run. His signature achievement was not one of workmanlike consistency, but rather an unbeatable combination of legendary staying power elevated by genuine and heretofore under-appreciated excellence.

ERIC MARSHALL WHITE, PhD, of Rocky Hill, New Jersey, is the Scheide Librarian and Assistant University Librarian for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at Princeton University Library. He has published widely on Gutenberg and fifteenth-century European printing. This is his fourth contribution to SABR publications. The day his stepfather took him to his first baseball game, specifically to see Hank Aaron play, ranks among his fondest childhood memories.

Notes

1. In an article published under various headlines by numerous Associated Press newspapers on January 23, 2021, Paul Newberry wrote: “Aaron was numbingly consistent, which explains how he broke Ruth’s record without ever hitting more than 47 homers in a season.” Kevin Sweeney, “Remembering Hank Aaron: A Look at His Most Impressive Stats, Feats,” Sports Illustrated (SI.com), January 22, 2021, wrote: “What allowed Aaron to surpass Babe Ruth was his longevity and consistency as much as his dominance. Aaron never hit more than 50 home runs in a single season and reached 45 just once, in 1971.” In fact, Aaron hit 45 home runs in 1962 and 47 in 1971.

2. “While Henry Aaron never hit more than 47 home runs in one big-league season, the right-handed-hitting slugger rode remarkable consistency and career longevity to a place atop the all-time homer chart.” “Daguerreotypes,” (The Sporting News, 1990), 174.

3. “It was a marathon with Hank, it wasn’t a sprint […] He’s in the pack but you think he’ll never break out.” Denzel Washington, quoted in Home Run: My Life in Pictures (Total Sports, 1999), v.

4. Richard Goldstein, “Hank Aaron, Home Run King Who Defied Racism, Dies at 86,” The New York Times, January 22, 2021: “He won the National League’s single-season home run title four times, though his highest total was only 47, in 1971.”

5. All home run statistics are available online at Baseball-Reference.com; a handy printed source is The Home Run Encyclopedia (Society for American Baseball Research, 1996).

6. Eddie Collins, Bobby Wallace, Rickey Henderson, Pete Rose, Rick Dempsey, and Omar Vizquel all played in more seasons than Aaron did, yet they hit 714 home runs combined. After Aaron’s 755, the next-best home run total in a 23-year career is Carl Yastrzemski’s 452; and after Aaron’s 47, the next-best seasonal mark for a 23-year man is 44, also by Yaz (he hit 17 away from Fenway Park).

7. Quotations from Hank Aaron, with Lonnie Wheeler, I Had a Hammer (Harper Collins, 1991), 159. Eddie Mathews hit 211 home runs in Milwaukee versus 241 away, while Joe Adcock hit 104 there and 135 away. Thus, Aaron “lost” fewer home runs to County Stadium than they did.

8. Road statistics, by themselves, are somewhat biased in that the hitter has not had the opportunity, or the chore, of playing an equitable portion of games in his own home park. As an example, for the sake of fairness, we could convert Ted Williams’s results at the seven road parks he visited into seven-eighths of his total and add back one-eighth of his home results, all multiplied by two, to recreate a full career of balanced competition: thus, 273 × ⅞ = 239 home runs on the road; 248 × ⅛ = 31 home runs at home; 239 + 31 = 270 adjusted home runs; 270 × 2 = 540 career home runs.

9. Greenberg and Mize lost prime years to military service in World War II. Another factor that limited Greenberg’s road totals is the fact that he never got to hit in Briggs/Tiger Stadium as a visitor. Foxx, for example, hit 9 home runs in 11 games in Detroit in 1932 and 7 more in 1937.

10. In Aaron’s actual rookie season, he hit 12 home runs on the road but only one in Milwaukee. All 13 were hit either in tie games or with the Braves behind in the score.

11. Two of these historic combined seasons, as well as Mantle’s top pairing, coincided at least partially with the American League’s expansion in 1961. Aaron’s top mark included the National League expansion year of 1962.

12. These statistics were calculated from road at-bat totals available online at Baseball-Reference.com.

13. According to Aaron’s autobiography Aaron (Crowell, 1974), written with Furman Bisher, 64–65, he had been drafted and was due to report for duty in October 1954, but the season-ending broken ankle he suffered on September 5 (on a sliding triple that completed a 5-for-5 doubleheader) put him on the deferred list; thus he enjoyed an uninterrupted career.

14. In Yankee Stadium, Mantle hit 76 home runs (one every 19.51 at bats) righthanded, and 190 home runs (one every 13.12 at bats) lefthanded; thus, his switch-hitting effectively neutralized the impediment that DiMaggio faced there (one every 22.7 at bats).

15. Yankee Stadium’s mercilessly lopsided blueprint held the brilliant center-fielder to 148 home runs in pinstripes, yet he was lethal with 213 home runs during his visits to other towns—fourth all-time when he retired, a mere 22 behind Foxx and 29 behind Gehrig, despite a much shorter career. Given back the three war years and situated in a normal home park, his superior rate per at bat would have put him second only to Ruth upon his early retirement, with about 500 career home runs.

16. On a road home runs-per-at-bat basis, Williams ranks immediately behind Ruth. Although Fenway Park nudged his .344 lifetime batting average up a few points, Williams hit 273 of his 521 home runs away from home (that is, 25 more homers in 68 fewer at bats). Alas, he missed so much playing time to his military service across two wars that his road numbers, impressive as they are, cannot begin to tell the whole story.

17. Craig Wright, Pages from Baseball’s Past: “Aaron Becomes a Home Run Hitter” (online by subscription, February 8, 2021), reinforces Aaron’s recollection that his surprising success on the “Home Run Derby” television show in December 1959 played a positive role.