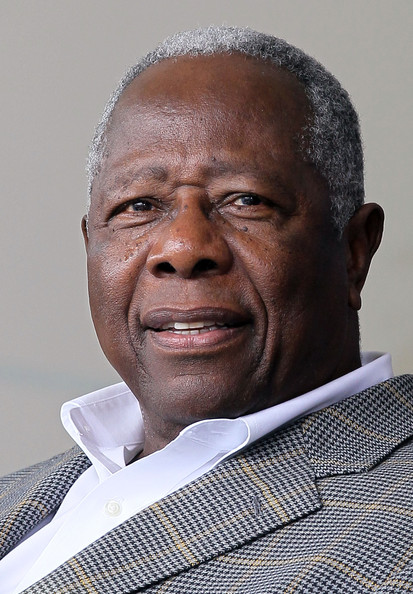

In Memoriam: Hank Aaron

By Jacob Pomrenke

It’s nearly impossible to overstate Henry Aaron’s greatness on and off the baseball field. His record of 755 home runs, shattering Babe Ruth’s iconic career mark while enduring relentless racist threats in the segregated Jim Crow South, transcended the game.

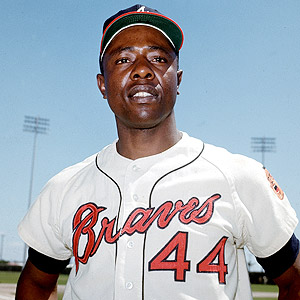

His quiet brilliance and proud spirit displayed over a 23-year Hall of Fame career with the Braves — who moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta, the heart and headquarters of the Civil Rights Movement, in the mid-1960s — made him one of the most visible Black men in American society, an idol to millions of fans and generations of ballplayers before his death at the age of 86 on Friday, January 22, 2021.

On the field, Aaron set all-time records for home runs (since broken by Barry Bonds), RBIs (2,297), and total bases (6,856) as one of the most complete all-around players baseball has ever seen. He had power, speed, smarts, and durability, hitting more than 20 home runs in every season between 1955 and 1974 — the year he surpassed Ruth with his 715th home run. But if you took away all of Aaron’s 755 home runs, he still would have recorded more than 3,000 career hits.

Off the field, Henry Louis Aaron was born on February 5, 1934, and grew up as the son of sharecropper parents in Mobile, Alabama, a hotbed of Black baseball talent despite the indignities of the Jim Crow era. Five years after Jackie Robinson integrated the all-white major leagues, Aaron began his professional career in the Negro American League as a cross-handed-hitting teenager with the Indianapolis Clowns, hitting .366 in 26 games before he signed with the then-Boston Braves. The Braves sent him to spring training in Waycross, Georgia, and later to integrate the Southern Atlantic League as one of its first Black players at age 19.

The Braves moved to Milwaukee after the 1952 season and Aaron made his National League debut two years later in Wisconsin, where he became a budding superstar. He led the Braves to a World Series championship in 1957, after hitting a dramatic walk-off home run to clinch the National League pennant, and winning MVP honors. In 12 full seasons in Milwaukee, Aaron displayed a steady brilliance, averaging 33 home runs and 109 RBIs. While his contemporaries Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays occasionally put up more eye-popping numbers, Aaron’s accomplishments took more time to appreciate.

After the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966, Aaron’s home run totals began to attract attention. He hit his 400th home run in his first year at the “Launching Pad” of Atlanta Stadium, then his 500th round-tripper in 1968. He surpassed Mantle, then Mays, and only Babe Ruth remained in his sights on the all-time leaderboard. When the 1973 season ended, Aaron had hit 713 home runs, one shy of Ruth’s mark.

Aaron had been outspoken earlier in his career about the racist threats he had endured during spring training and around the major leagues, but the public revelation in the early ’70s of all the hate mail he received during his record-breaking run came as a shock to many white baseball fans. As Bill Johnson wrote in his SABR biography of Aaron:

A self-described “50 year old White Woman from Massachusetts” wrote, “To Hank Aaron: A Rotten Nigger….you must have made every intelligent white man hate you and your opinions even more…”. Describing those letters as mere irrational raving is reasonable nearly forty years after the chase, but at the time, with a black player pursuing the record of a white one, the threats seemed very real.

When Aaron finally returned to the field in 1974 and broke Ruth’s mark on April 8 in Atlanta with a home run to left field off Los Angeles Dodgers left-hander Al Downing, he said, “I just thank God it’s all over.”

Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully paid tribute to Aaron’s perseverance in his call of No. 715:

“What a marvelous moment for baseball; what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia; what a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron. … And for the first time in a long time, that poker face of Aaron shows the tremendous strain and relief of what it must have been like to live with for the past several months.”

Aaron was traded by the Braves back to his old home in Milwaukee, where he played out the rest of his career with the American League’s Brewers, finishing with 755 home runs when he retired in 1976. He was a near-unanimous selection to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1982 with 97.8 percent of the writers’ votes.

He moved into the Braves front office — one of the few Black executives in baseball — as Vice President of Player Development from 1977-89, playing a key role in drafting future Hall of Famer Tom Glavine, and All-Stars David Justice, Ron Gant, and Ryan Klesko to help build the Braves’ dynasty of the 1990s.

Aaron continued to serve as an ambassador and special assistant into the 21st century with the Braves organization, which retired his number 44 and later erected a statue of him outside their former home of Turner Field in downtown Atlanta. The address was 755 Hank Aaron Drive — just a long fly ball away from where a proud Black man from Alabama had changed the course of baseball history with one swing of the bat.

Related links:

- Tyler Kepner: Hank Aaron Stood Out Even in a Group of Hall of Famers (New York Times)

- Jayson Stark: Hank Aaron by the numbers (The Athletic)

- Claire Smith: Hank Aaron and his eternal connection to Black baseball (The Undefeated)

- Howard Bryant: Let us appreciate the grace and uncommon decency of Henry Aaron (ESPN.com)

- Stephanie Apstein: Hank Aaron Never Forgot How America Treated Him. We Shouldn’t, Either (Sports Illustrated)

- Jason Schwartz: The History of Baseball Cards, as told through Hank Aaron (SABR Baseball Cards Committee)

Originally published: January 22, 2021. Last Updated: January 25, 2021.