The International Association of 1877–80

This article was written by Woody Eckard

This article was published in Spring 2024 Baseball Research Journal

Organized professional baseball began in the 1870s with three independent entities. The first was the National Association, which operated from 1871 to 1875. This was followed in 1876 by the National League, which has operated continuously to the present day. The third was the International Association, so called because it initially included Canadian teams. It operated from 1877 to 1880, albeit with an 1879 name change.

While the International Association was overshadowed by the National League, it nevertheless saw itself as a counterpoint, aspiring to approximate parity, and many contemporaries viewed it in the same light. As David Nemec notes, the organizers of the International “in no sense viewed themselves as ‘minor’ operators.”` According to the contemporary New York Clipper: “Just as the rivalry of the International Association is a benefit to the League, so is the League an advantage to the Association. Each spurs the other on.”2 Tom Melville quotes one period newspaper as saying that “international clubs have batted and fielded better than the League teams,” and another claiming that “international clubs can play as good a game as the League nines.”3 He also notes that “the International Association…was certainly presenting the National League with a very troublesome, if not outright threatening, challenge to [its] claim as the top baseball organization.”4

The main purpose of this article is to provide a concise but detailed history of the International Association, “about which little is known and confusion exists.”5 To my knowledge, it is the first such undertaking. Aside from shedding light on a significant early professional baseball organization, it enables a discussion of how close the International Association came to parity with the National League. The author has assembled a database containing the complete game results for all International clubs in each of its four seasons, including the numerous games between International Association and National League clubs. The primary source is the weekly New York Clipper newspaper, supplemented by Newspapers.com6

THE FIRST TWO PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

The National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NA) was founded in 1871, although professional clubs had begun operating openly two years earlier.7 Its main purpose was to provide structure for the national championship competition. The key feature of the NA was its loose-knit, decentralized structure. Membership was open to any club able to pay a nominal entry fee. There were no other restrictions or conditions such as financial backing, management strength, or host city population as a measure of potential fan base. Multiple clubs in the same city were allowed. In addition, while clubs were required to play a series of championship games with each other club, scheduling was generally left to bilateral arrangements among members with no oversight mechanism to assure compliance. There were no other professional organizations during its five-year existence, perhaps in part because of the open entry policy.

The NA’s haphazard structure produced operational instability, with many between-season membership changes and midseason failures. It had 25 different clubs, with annual membership ranging from eight to 13. On five occasions, cities had multiple clubs, including three in Philadelphia in 1875. Seventeen different cities were represented, ranging in population from the likes of New York and Philadelphia down to such small towns as Keokuk, Iowa, and Middletown, Connecticut. It was mainly an eastern organization. During its middle three years of operation, there were only two western clubs, meaning west of the Allegheny Mountains.

In 1876, the NA was replaced by the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs, which addressed many of the NA shortcomings.8 Six of the NA’s best clubs joined, causing it to fold. The NL’s largely unanticipated creation was announced in February 1876, too late for another organization to form that season. Entry into the National League was subject to review. Membership was restricted to a single club from cities with populations of at least 75,000 to promote financial viability, although a few early exceptions were made to the population requirement. A $100 annual membership fee was required, equivalent to roughly $3,100 in 2023 dollars.9 Also, the number of members was limited to six or eight during its first 16 years of operation. In 1877, scheduling was centralized, creating the first fixed schedule, and in 1878, for the first time, all six teams completed their planned 60 games. Importantly, clubs were expected to complete their schedule. As noted by Michael Haupert: “League-created scheduling would become a bedrock upon which the stability of leagues has been built ever since.”10 In the late 1800s, the NL achieved geographical balance in most years by locating an equal number of teams in the East and West.

The National League began as an eight-team circuit. After the first season, the Mutuals of Brooklyn and the Athletics of Philadelphia were expelled for canceling scheduled end-of-season road trips. In 1877 and 1878, the NL operated with six clubs, returning to the eight-club format from 1879 to 1891. In 1877, Cincinnati disbanded in mid-June. However, a second Cincinnati club was quickly organized, beginning play three weeks later, and managed to finish the first club’s schedule.11 In 1879, Syracuse also folded, failing to complete its schedule with 14 games remaining. By modern standards, the National League initially experienced significant membership instability, with 16 different clubs in the first five years. Nevertheless, that improved upon the NA’s 25 clubs during its five-year existence and its many more midseason failures.

THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION

After months of preliminary discussions beginning in the fall of 1876, the International Association (the International) was organized at a Pittsburgh meeting on February 20, 1877.12 Twenty-one clubs were represented, although only seven later entered the initial championship competition. After the two Canadian clubs departed, the name was changed to the National Association in 1879. Aside from sponsoring the competition, its other main function was to regulate the player market, mainly to prevent contract jumping (“revolving”) via mutual contract recognition among all members, including those not contending for the championship. Our focus is on clubs involved in the championship competition. It should be noted at the outset that a national economic depression had begun in 1873 that lasted until the spring of 1879.13 It no doubt contributed to the International’s problems. This was an inauspicious time to be starting a major new economic endeavor.

The International adopted the NA’s unstructured organizational model, eschewing the National League model. In fact, it was largely inspired by a rejection of the NL’s exclusive entry policy. As we shall see, this decision was a fundamental mistake.

The result was what David Pietrusza described as a “loose confederation” of clubs.14 Initially, general membership was open to any professional club for a $10 fee, and an additional $15 was required to enter the championship competition.15 These fees are roughly $310 and $460, respectively, in 2023 dollars. Both memberships were for a single year. There were no other restrictions or conditions. In 1878, each of these fees were doubled. Applications were to be submitted each year by April 1, with the championship season running from April 15 to October 15. Game admission fees were set at 25 cents, in contrast with the National League’s 50 cents, respectively about $7.70 and $15.40 in 2023 dollars. Gross gate receipts were to be split evenly, except for a guaranteed minimum of $75 for the visiting team, about $2,300 in 2023 dollars. Geographically, the International was concentrated in the northeastern US, with 13 cities in Massachusetts and New York alone, although no clubs were in Boston, Brooklyn, or New York City. Each championship contender was required to play a specified number of championship games with each other contender. These were to be scheduled by a committee at the beginning of the season, but implementation was haphazard. Instead, bilateral scheduling among clubs seemed to be the norm and, as in the NA, no oversight mechanism existed. In fact, there seemed to be no expectation that clubs would complete their schedule of championship games. For example, an algorithm was defined for adjusting team standings for presumed midseason departures, of which there were many.

There was substantial instability in the number of championship contenders over the International’s four-year existence. Seven clubs participated in the championship competition in the initial year, followed by 13 in 1878 and nine 1879, then only four in the unfinished final season. A total of 23 different clubs competed during the four years, and 22 cities were represented. In 1879 Albany, New York, began the season with two clubs. Also, there were late entrants in 1878 and 1880, and on four occasions clubs relocated midseason. Of the 22 cities, 13 were members for only one year, and another seven for two. The Manchester Club of New Hampshire was in for three years. Only Rochester was represented in all four, albeit with three different clubs.

In-season instability was also a significant problem as many clubs failed to complete their schedules. Fourteen disbanded for financial reasons, two were expelled for rule violations, and one withdrew voluntarily, completing its season as an independent. In contrast, during this same period, the National League had 14 member cities and clubs and only two failures.

A critical result was confusion regarding the International pennant race. By midseason, newspapers often were reporting multiple standings in the same issue based on various assumptions about how the International’s Judiciary Committee would make adjustments for departed clubs. Also, members were allowed to play exhibition games among themselves during the championship season, creating additional confusion about which games counted. As Brian Martin observes, fans “were disappointed when a game believed to be for the pennant turned out to be an exhibition.”16 Last, because of the two membership classes, early in the season there was often confusion about which members were involved in the championship competition. In all three years that a champion was declared, winners were not known for sure until the Judiciary Committee’s report at the annual convention several months after the season’s end.

A large difference existed between the International Association and the National League in terms of member city population, with the NL in much larger cities. During 1877–80, it had 10 cities with populations exceeding 100,000, while the International had only four.17 At the other end, all NL cities exceeded 50,000, while the International had no fewer than 11 smaller than that, with three under 10,000. Overall, NL city population averaged about 210,000 during that four-year period, while the International averaged only about a third of that: 69,700. In fact, Ted Vincent argues that “the International…really represented…the organized expression of an immense popularity of baseball in the smaller industrial city.”18 At no point did the International Association and the National League share the same city.

Despite its shortcomings, the International Association was given favorable press by the leading national baseball newspaper of that time, the New York Clipper. Its baseball editor, Henry Chadwick, was the top baseball journalist of the era and is a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.19 The Clipper’s coverage of the International was similar to that of the NL regarding the championship competition and the reporting of club standings. Chadwick had taken a strong editorial position critical of the NL’s exclusive membership policy immediately upon its inception. He preferred the open entry approach of the NA, which was adopted by the International, and hoped for the newer league’s success. Neil Macdonald describes Chadwick as “the leader of the reportorial minority who opposed [the NL’s] creation.”20 One manifestation of Chadwick’s antipathy towards the National League was his attempt to undermine the claim that its restrictive business model produced higher quality baseball.21 To this end, from 1877 through 1880, he periodically published articles in the Clipper pointing out that National League clubs lost many of their numerous exhibition games against non-NL opponents. Focusing mainly on games against International clubs, these articles summarized NL losses, but the many more NL victories usually were not reported, a fact that revealed Chadwick’s agenda. The result was favorable, if biased, national publicity for the International.

THE NATIONAL LEAGUE REACTION

Although they did not compete directly for fans, the National League was concerned about the International as a competitor for players and prestige, which in turn could indirectly affect home-fan demand. One expression of this concern was the League Alliance, an agreement initiated in February 1877 between the National League and several independent clubs, ostensibly for mutual contact recognition.22 As Brock Helander notes: “The League Alliance arose as the National League…response to the perceived threat of the International Association.”23 Having expelled clubs in its two largest cities, Brooklyn and Philadelphia, its lineup was reduced to six clubs for 1877, with only two from the much more populous East. As noted above, at this time the NL’s future was still uncertain.

The weekly New York Clipper first announced the Alliance on January 20, 1877, in the same issue that it first announced the February 20 convention to organize the International Association. A National League representative, described anonymously as “a gentleman from Chicago” (likely Albert Spalding), provided the particulars of the Alliance proposal.24 Included was a statement strongly suggesting a preemptive motive: Non-NL clubs would “derive far more substantial advantages from this arrangement than from any experimental association that they might organize independently.”25 In fact, a St. Louis Globe-Democrat article on the Alliance was headlined: “War Declared Between the League and the Internationals.”26

While League Alliance member clubs would be protected from player “pirating” by other members, the subtext was that the unprotected players on non-members might be “fair game.” Also, independent clubs contemplating International membership might be deterred by fears of retribution by the National League. Concerns regarding NL motives were reinforced by a stipulation in the Alliance agreement that the Judiciary Committee charged with resolving disputes would be composed only of NL clubs, excluding non-league members. Initially, International clubs were not barred from joining. However, in the fall of 1877 the NL added a rule that non-NL clubs belonging to the Alliance could not be members of any other organization, effectively barring International clubs.27 This, of course, made clear its true purpose as an anti-International vehicle.

Another expression of National League concern was the so-called Buffalo Compact, signed at a meeting in Buffalo on April 1, 1878. It gave preferential treatment to six of the better International clubs in scheduling postseason games with National League clubs and established mutual recognition of player contracts, in effect accepting these clubs into the Alliance.28 Exceptions were granted to the rule barring membership in other organizations, allowing them to remain as members of the International. Four of the other seven 1878 International clubs reacted by refusing to schedule games with National League clubs, although none resigned over the issue. Both the League Alliance and the Buffalo Compact were generally interpreted as attempts by the National League to undermine the International by preempting possible new member clubs, limiting player availability, and sowing internal discord.29 However, the International had nobody but itself to blame for its many difficulties.

THE INTERNATIONAL’S FOUR SEASONS

The International Association completed only three of its four seasons. In 1880, at most, four clubs competed at any one time, and that just for a short period. By the end of July, only two clubs remained and the International was effectively history, fading away with no formal announcement of disbanding.

As noted above, numerous intra-International exhibition games and adjustments for failed teams confused the standings. The number of official championship games counted at season’s end typically was half or less of the total number of intra-International games. We report both below. Nevertheless, by either measure, in its three full seasons the International’s championship competition was reasonably competitive, with no dominant clubs, unlike the old National Association of 1871–75. Also, only in 1878 was there some totally “out-of-it” teams, when the Alleghenys and Hartfords combined for a 4–40 record in all International games played. In contrast, clubs at both extremes were a problem for the NA.

The 1877 Season

The seven clubs that entered the inaugural championship competition in 1877 were the Alleghenys of Allegheny City (a city later annexed by Pittsburgh); the Buckeyes of Columbus; the Live Oaks of Lynn, Massachusetts; the Manchesters (New Hampshire); the Maple Leafs of Guelph, Ontario; the Rochesters; and the Tecumsehs of London, Ontario30. Only Allegheny City, Columbus, and Rochester had 1880 populations exceeding 50,000. Newspaper reports indicated that more were expected to enter, but none did. Several other clubs joined for player contract protection only. The Buckeyes and Live Oaks both disbanded late in the season, in mid-September, while the others completed their schedules.31 By the standards of the time, this was a successful start. For example, the next professional organization, the minor four-club Northwestern Base Ball League of 1879, disbanded in mid-July after only three months of operation.32

The 1877 International standings are shown in Table 1. Each contender was supposed to play four championship games against each other contender, but it wasn’t until early September that the International decided that it would be the first four such games that would count.34 The left panel of Table 1 is the official championship standings as determined by the International Judiciary Committee and made public at the annual convention in February 1878.35 The committee also resolved an ongoing dispute between the top two contenders regarding which games would count in their championship records. The right panel of Table 1 shows all games between members, including exhibitions and championship games officially excluded because of adjustments for games with the disbanded Buckeye and Live Oak clubs. The Tecumseh Club (Figure 1) was the official champion with a 14–4 record, and the Alleghenys were not far behind at 11–5.

Note that, with the four-game requirement and seven contenders, a full season with all teams completing their schedule would have been only 24 championship games each. As it happened, with the excluded games, only the Tecumsehs had as many as 18 games that counted. The Live Oaks played no games against two members before they disbanded, and so none of their games counted for any team, per the adjustment algorithm.

Meanwhile, the National League had a 60-game schedule, with all teams playing at least 57 games that counted.36 This was another problem for the Internationals: their infrequent games made it difficult to establish brand identity. As the Clipper put it on July 28: “The contest for the championship of the International does not progress very fast, the meetings between the contesting nines being few and far between.”37

The 1878 Season

The 1878 season saw the addition of eight new clubs, with five holdovers, for a total of 13.38 Only the Buckeyes and Maple Leafs elected not to reenter.39 The net increase of six, of course, was a positive sign; the new clubs apparently found the International attractive based on the 1877 showing. The additions were New York teams the Buffalos, the Crickets of Binghamton, the Hornells of Hornellsville, the Stars of Syracuse, and the Uticas; and Massachusetts teams the Lowells, New Bedfords, and Springfields.40 Of these additions, only Buffalo, Lowell, and Syracuse had populations exceeding 50,000.

On April 20, 1878, the International’s Scheduling Committee published in the New York Clipper a complete season’s schedule of championship games for all 13 members.41 This was likely inspired by similar set schedules of championship games first announced by the National League at the beginning of the 1877 season. The committee explicitly “permit[ted] clubs to arrange State championship and exhibition games on any open dates” during the championship season.42 The exhibitions could be with International clubs. And the state championship games in several cases involved other International members, i.e., they were also championship games but not for the International, adding to the confusion.

Unfortunately, membership turmoil started almost immediately, and the official schedule became largely a dead letter.43 First, the New Bedfords withdrew on May 5, shortly after entering, finishing the season as an independent. At that point the New Haven Club entered, picking up the New Bedford schedule. About two weeks later, the New Havens moved to Hartford, adopting the Hartford name. This thread was concluded when Hartford was expelled from the Association on July 17 for failing to pay a visiting International club the required share of proceeds from a home game. The Live Oaks also moved, merging with the existing independent Worcester Club in late May, and adopting that club’s name. The combined club remained an International member, assuming the Live Oaks’s record and schedule. These disturbances were compounded by several midseason failures. The Alleghenys disbanded on June 8, the Crickets on July 9, the Hornells on August 21, the Tecumsehs in late August, the Rochesters on September 7, and the Worcesters in mid-September.44 Each of these failures created another round of speculation regarding adjustments to the standings. Confusion about the championship race existed for most of the summer.

On September 21 the Clipper observed that “things have become so mixed that the [International] Association Judiciary Committee are likely to become insane before they arrive at a satisfactory conclusion” regarding the standings (Figure 2).45 A January 4, 1879, Clipper review article described the 1878 season as “chaotic,” recommending “a tighter rein [on] clubs entering for the championship competition” to exclude those “unable to carry out their engagements.”46 The 1878 tumult stood in sharp contrast to the mostly successful inaugural season.

The final standings are shown in Table 2. As with Table 1, the left panel is the official standings as finally sorted out by the Judiciary Committee and presented at the annual convention of February 19–20, 1879.47 The right panel shows all games between members, including exhibitions, state championship games, and adjustment exclusions. The Buffalos (Figure 3) were atop the official standings, with a 24–8 record, and the Stars were a close second at 23–9. Of the total of 345 games actually played between International clubs, only 154, less than half, counted in the standings. All of the New Bedford and expelled Hartford games were excluded, with the number counted for remaining clubs varying from 11 to 32. A full season would have been 48 games given the four-game requirement and assuming no departures. Meanwhile, all six National League teams completed their 60-game schedules.

The 1879 Season

The 1879 edition of the International saw nine clubs sign up for the championship competition.48 The Canadians having withdrawn, it was renamed the National Association. However, we will continue to use the International name to avoid confusion with the old National Association of 1871–75.

After the chaotic 1878 season, the new lineup saw a major turnover. Nine clubs departed, including the Buffalos and the Stars, who were admitted to the National League. On the plus side, four new clubs joined: the Albanys and Capital Citys, both from New York’s state capital; the Holyokes, in Massachusetts, and the Nationals of Washington. Both Albany and Washington had populations exceeding 50,000. The net reduction of five implied a negative market reaction to the 1878 turmoil; the open entry policy also meant “open exit.” There is no evidence that the International followed the Clipper’s advice to modify the open entry policy or took any other steps to improve its operation. While two of the three newly admitted 1879 cities had large populations, this was most likely happenstance.

As in the previous year, a significant proportion of clubs did not complete their seasons, again creating confusion about team standings.49 First, the Manchesters and Uticas disbanded in July, as did the Springfields in early September. Second, in early May the Capital City Club relocated to Rochester as the Hop Bitters Club, which then disbanded in mid-July.50 This thread ended when the International’s Judiciary Committee later determined that the relocation had been in violation of its rules in the first place, and therefore retroactively expelled the Hop Bitters.51 The standings were then adjusted to exclude all their games. On July 26, the Clipper reiterated its January 4 recommendation that the International should “limit championship contests to clubs which…carry out their appointed season’s programme [sic].”52

The 1879 standings are shown in Table 3, following the same format as Tables 1 and 2. The Albanys were the champion with a 25–13 record, and the Nationals were not far behind at 22–16. Both were new members. Note that in the official standings, again as reported in the Clipper, four clubs had 38 games that counted; the “required” number of games against each member had been increased to eight.53 Once more, less than half of the actual games played between International members counted. And again, the difference can be attributed mainly to exhibition games. The Clipper of July 12 argued that those games should be abolished because they “create confusion in making up the record.”54 National League rules prohibited intraleague exhibitions during the championship season.

A second consecutive problematic season for the Internationals may have influenced the National League’s decision to implement its player reserve system in the fall of 1879. Perhaps the International was no longer seen as a competitive threat in hiring players. In addition to offering generally lower salaries, men not signing with a winning team likely would be scrambling for a new job by midseason. With the National League, a steady paycheck until the season’s end would be much more likely.

Despite its many difficulties, the International Association nevertheless managed to complete three seasons and move on to a fourth. The next new professional organization to achieve this was the major league American Association of 1882–91.

The 1880 Season

As noted above, the 1880 season was a rump affair. Only three clubs initially entered for the International championship.55 They were the Albanys, the Baltimores, and the National Club. The Albanys and the Nationals were holdovers after finishing first and second in 1879. The International Association clearly was failing after two chaotic seasons. Nevertheless, the championship competition was launched, with newspapers dutifully reporting three-club standings. A newly formed Rochester club joined on June 8 to make it four until the Baltimores disbanded three weeks later.56 On July 9, the National Club moved to Springfield to reduce travel costs with the remaining Albany and Rochester clubs. Springfield had been an International member in 1878 and 1879. Two other clubs were falsely rumored to have joined midseason, occasionally included in the standings by some newspapers.

The coup de grace occurred when the Albany Club disbanded around July 20, leaving only the Rochesters and Nationals. On July 24, the Clipper published what amounted to an obituary, attributing the International’s demise to “bad management,” although an almost total absence of management might be closer to the truth.57 The article further noted that “the Nationals have joined the League Alliance…and thereby have been obliged to resign from the [International] Association…thus ends the ‘strange, eventful history’ of the Association.”58 There was no published announcement by the International that it had dissolved and apparently no champion was declared. Newspapers, of course, quit publishing standings. Nevertheless, for the record, Table 4 presents the standings for all games between the four 1880 members, as determined by the author. The National Club clearly dominated with a 32–11–3 record, and the other three all under .500.

THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION VS. THE NATIONAL LEAGUE

The relative strength of the International and the NL is of interest, given that it was the subject of debate among contemporaries. The most straightforward assessment is to look at the results of the numerous games between clubs in the two organizations. In fact, contemporary newspapers often published summaries of outsider victories over NL clubs for that reason. For example, the Clipper of September 28, 1878, reported a detailed analysis of 1878 National League vs International Association games.59

In evaluating the results of these exhibition games, one must keep in mind that NL clubs often did not have their A-team on the field. Exhibitions were an opportunity to, e.g., provide the “change” pitcher and/or catcher some practice, as well as any reserve players. Also, player motivation was likely lower in these non-championship contests. Nevertheless, NL clubs needed to be careful lest losses to weak clubs damage their brand, including raising suspicions of throwing games, particularly after the Louisville scandal of 1877.60 Another factor was that these games were usually on the opposing team’s home field, often meaning a home team umpire. And its players may have had an extra motivation, perceiving the game as a tryout for the visiting NL club.61 Thus, the International’s overall performance in these exhibitions must be viewed only as an upper bound on its quality relative to the National League.

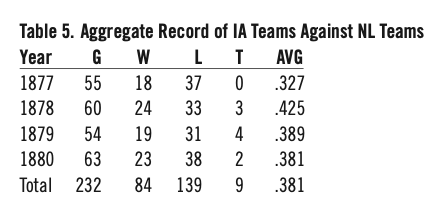

Table 5 summarizes interleague game results by year for the 232 such games yielded by our search over the 1877–80 period. During those four years, International clubs were 84–139–9 versus all NL clubs, a .381 winning average.62 By comparison, the National League’s second-division clubs had an almost identical winning average (i.e., vs. all NL clubs) of .376 during the same period. A similar number of interleague games occurred in each year, varying from 54 to 63, the maximum occurring in 1880 despite the International having only four members. The winning average was also similar in each of the four years, varying from .327 to .425. Recall that this comparison yields only an upper bound on the International’s relative quality. Accordingly, these data indicate the average International Association club was certainly of lower quality than the average National League club.63

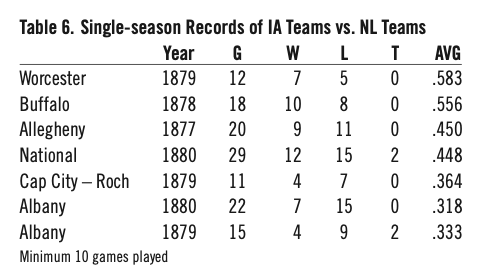

It is also interesting to look at the record of individual clubs against the National League. Table 6 presents the seven International teams with at least 10 such games in a single season. The 1880 National Club won the most with 12, but also lost 15 (plus 2 draws). The 1878 Buffalos were 10–8 and in 1879 the Worcester Club was 7–5. The significant number of games played by the Albanys and Nationals in 1880 may have been attempts at auditioning for National League membership, albeit unsuccessfully.

Another consideration is that three International clubs were “promoted” to the National League: the Buffalos and Stars for the 1879 season and the Worcesters in 1880. The Buffalos and Stars were first and second in the 1878 International race, and Worcester finished fourth in 1879. The NL actions here may have been, in part, another attempt to undermine the International by pirating some of its leading teams. Buffalo did well in 1879, finishing third in the NL with a 46–32 record, and Worcester was respectable at 40–43 in 1880, landing in fifth place in the eight-team circuit. The 1879 Stars did poorly, however, finishing in seventh place with a 22–48 record and disbanding before the season’s end. Nevertheless, the International provided the NL with half of its six new clubs in 1878–81.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

How close did the International Association come to achieving its aspiration of rough parity with the National League? Its history suggests that any such argument rests mainly on the 232 games against NL teams. Our analysis indicates an overall winning average of .377. However, some International clubs had more respectable individual records, and three were deemed worthy of NL membership. Nevertheless, overall, the average International club was, at most, roughly equivalent to the National League’s average second-division clubs.

The remainder of the International’s ledger provides little support for parity. First, it was basically regional, mainly confined to eastern US cities, with more than half its clubs in only two states. Columbus, Ohio, was the westernmost member, and that for only a single year, and only four other of its 22 cities qualify as western by 1870s standards.

The International’s haphazard operation is a more serious issue. This produced highly unstable membership, muddled championship competitions, and many clubs in cities that were too small to support them. These related problems arose from the adoption of the old National Association (1871–75) organizational model that Pietrusza aptly described as “rather miserable.” For example, the open-entry policy yielded 11 clubs in cities with populations under 50,000, while the National League had none. This contributed to high rates of year-to-year membership turnover and midseason failure that were a particular problem for the International. It had 14 failures, while the NL had only two during the same period. In each of its three completed seasons, the championship was in dispute for months after the season ended. In sum, operationally it was, for the most part, a proverbial train wreck. Per the Clipper, “bad management” produced its…“strange history.”65

Thus, the short answer to the question of how close the International came to parity is: “not very.” The International’s operating model was not thrust upon it. Also, during its four years of existence, apparently no attempt was made to correct the many shortcomings, despite newspapers not being shy about pointing them out. Had the National League model initially been adopted, or had the International been able to learn from its mistakes, it might have achieved rough parity. Perhaps the International Association’s main legacy was that the juxtaposition of its performance on that of the National League’s in 1877–80 provided baseball entrepreneurs clear evidence that the NL’s operating model was superior.

DR. WOODY ECKARD is a retired economics professor living in Evergreen, Colorado, with his wife, Jacky, and their two dogs, Petey and Violet. Among his academic publications are 13 papers on sports economics, five of which relate to MLB. More recently he has published in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, The National Pastime, and Nineteenth Century Notes. He is a Rockies fan and a SABR member for over 20 years.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for helpful comments from two reviewers.

Notes

1. David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball, 2nd ed. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 130.

2 “The International Association,” New York Clipper, January 4, 1879, 325. The Clipper was a weekly newspaper self-described as “The Oldest American Sporting and Theatrical Journal.” It was the leading national baseball journal of that period.

3 Tom Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2001), 104–5.

4 Melville, Early Baseball, 104.

5 Brian Martin, The Tecumsehs of the International Association: Canada’s First Major League Baseball Champions (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2015), 9.

6 The Clipper reported box scores on virtually all professional games. Issues can be accessed via the Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections, University of Illinois Library: https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=cl&cl=CL1&sp=NYC&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN–

7 For a history of the National Association, see William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871–1875, Revised Edition (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2016)

8 For histories of the early National League, see Melville, Early Baseball, and Neil Macdonald, The League That Lasted: 1876 and the Founding of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2004).

9 These and all other conversions to 2023 dollars herein are based on a 19th century Consumer Price Index series available at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/about-us/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator/consumer-price-index-1800-

10 Michael Haupert, “In the Face of Crisis: The 1876 Winter Meetings,” in Jeremy K. Hodges and Bill Nowlin, eds., Base Ball’s 19th Century “Winter” Meetings: 1857–1900 (Phoenix: SABR, 2018), 140.

11 MLB today recognizes the two as a single combined club, although at the end of the 1877 season the National League excluded both clubs from its official final standings. For example, see Woody Eckard, “The 1877 National League’s Two Cincinnati Clubs: Were They In or Out, and Why the Confusion?” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 52, no. 1 (2023), 80–85.

12 “The International Association,” New York Clipper, March 3, 1877, 387. This article reported the International’s founding convention, giving its full name as “International Association of Professional Baseball Clubs,” and the Clipper used the same name again reporting the second annual convention. A search of newspapers.com yielded only two other contemporary newspaper reports of the founding that included the full name. But both had it as “International Association of Base-Ball Players” (“Baseball: The International Association,” Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1877, 7; and “The National Game,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 22, 1877, 4). The two modern historians with the most extensive coverage of the International both use the same third version: “International Association of Professional Base Ball Players” (Martin, The Tecumsehs, 264; and David Pietrusza, Major Leagues: The Formation, Sometimes Absorption and Mostly Inevitable Demise of 18 Professional Baseball Organizations, 1871 to Present (Lemurpress.com: Lemur Press, 2020), 48). This is one example of the “confusion” that exists regarding the International, as noted by Martin (see endnote 5). The reader may pick and choose.

13 Per the official business cycle dating of the National Bureau of Economic Research: https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions

14 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 28.

15 “The International Championship,” New York Clipper, March 31, 1877, 2. This article contains the complete rules governing the International Association championship competition.

16 Martin, The Tecumsehs, 100.

17 This count combines the populations of Allegheny City and Pittsburgh. All population data reported herein are from the 1880 U.S. Census.

18 Ted Vincent, Mudville’s Revenge: The Rise and Fall of American Sport (New York: Seaview Books, 1981), 142.

19 Chadwick is a Hall member as an “executive,” based mainly on his contributions to the development of baseball rules and scoring conventions.

20 Macdonald, The League That Lasted, 61.

21 For example, see Woody Eckard, “Henry Chadwick and the National League’s Performance vs. ‘Outsiders,’” Baseball Research Journal 52, no. 2 (2023), 67–76.

22 The League Alliance did not sponsor a championship competition, although newspapers occasionally reported standings. See Brock Helander, “The League Alliance,” SABR, https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/the-league-alliance/, last accessed December 20, 2023..

23 Helander, “The League Alliance.”

24 “The League and Its Work,” New York Clipper, January 20, 1877, 339. See also “Ball to the Bat,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 15, 1877, 5; “Baseball: Spalding Indulges in a Defense,” Chicago Tribune, January 28, 1877, 7; and “Spalding’s Scheme,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 28, 1877, 7. Spalding was the star pitcher on the 1876 National League champion Chicago club, and its president, William Hulbert, was also the National League president. Spalding was no doubt acting as his agent.

25 “The League and Its Work,” New York Clipper.

26 “Ball to the Bat,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

27 For example, see “Ball Talk,” New York Clipper, December 22, 1877, 306; and “The International Association,” New York Clipper, December 29, 1877, 314.

28 For example, see Helander, “The League Alliance”; “The Buffalo Conference,” New York Clipper, April 13, 1878, 21; and “The Buffalo Conference and Its Work,” New York Clipper, April 20, 1878, 29. The International clubs were the Buffalos, Lowells, Rochesters, Springfields, Stars, and Tecumsehs.

29 See Helander, “The League Alliance.”

30 “The International Championship,” New York Clipper, May 26, 1877, 66. At this time, Allegheny City was a separate polity located across the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh. It was annexed by Pittsburgh in 1907.

31 “The International Championship,” New York Clipper, September 29, 1877, 210.

32 “The Northwestern League,” New York Clipper, July 26, 1879, 139.

33. Winning average counts draws as one half of a win each.

34 See “International Championship,” New York Clipper, September 1, 1877, 179; and “The International Championship,” New York Clipper, September 8, 1877, 187.

35 “The International Convention,” New York Clipper, March 2, 1878, 386.

36 “1877 National League Team Statistics,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/NL/1877.shtml.

37 “International Pennant Race,” New York Clipper, July 28, 1877, 138.

38 “International Ass’n Movements,” New York Clipper, April 6, 1878, 10.

39 The Buckeyes and Maple Leafs had disbanded in September of the previous year, but it was not uncommon at this time for disbanded clubs to reorganize and resume play in the next season or even in the current one.

40 The 1877 Lowells were the top independent club in the country that year, comparable in quality to the National League champion Bostons. See Woody Eckard, “The Lowell Base Ball Club of 1877: National Champions?,” Nineteenth Century Notes (SABR), Bob Bailey and Peter Mancuso, eds., (Summer 2022), 1–5.

41 “The International Association,” New York Clipper, April 20, 1878, 29.

42 “The International Association.”

43 A detailed summary of club departures can be found in “Baseball—The Buffalos and the League,” The Buffalo Commercial, November 26, 1878, 3.

44 “Baseball—The Buffalos and the League.”

45 “The International Arena,” New York Clipper, September 21, 1878, 202.

46 “The International Association,” New York Clipper, January 4, 1879, 325.

47 “The International Convention,” New York Clipper, March 1, 1879, 386.

48 “The Coming Season,” New York Clipper, March 29, 1879, 5.

49 “The National Arena,” New York Clipper, October 11, 1879, 226.

50 Hop Bitters was the name of a patent “medicine” whose manufacturer decided that owning a baseball team would be good advertising. See Tim Wolter, “The Rochester Hop Bitters: A Dose of Baseball in Upstate New York,” The National Pastime 17 (1997), 38–40.

51 “The Rochester Club,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 22, 1879, 3.

52 “The National Arena,” New York Clipper, July 26, 1879, 138.

53 “The National Association Convention,” New York Clipper, February 28, 1880, 389.

54 “The National Arena,” New York Clipper, July 12, 1879, 123.

55 “The National Association’s Schedule,” New York Clipper, May 1, 1880, 44.

56 “The National Association Clubs,” New York Clipper, July 24, 1880, 138.

57 “The National Association Clubs.”

58 “The National Association Clubs.”

59 “League vs. International,” New York Clipper, September 28, 1878, 210.

60 Four Louisville players were expelled for throwing games, leading to the club’s resignation from the National League. For example, see Melville, Early Baseball, 92–93.

61 Excluding the six International clubs that joined the Buffalo Compact of 1878 and thus were protected from National League raiding.

62 Scott Simkus reports International Association results against the National League, apparently for 1877–78, although he does not state the years. He found that the International’s record was 35–55–5 (.395), a total of 95 games (Scott Simcus, Outsider Baseball: The Weird World of Hardball on the Fringe, 1876–1950 (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014), 19). For 1877–78, I found 115 interleague games, with the International record at 42–70–3 (.378), a similar winning average.

63 A t-test rejects the null hypothesis of a .500 winning percentage at the 2% significance level (p = .011), despite the small sample size of four years.

64 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 48.

65 “The National Association Clubs,” New York Clipper.