The Marathon Game: Endless Baseball, its Prelude, and its Aftermath in the 1909 Three-I League

This article was written by William Dowell

This article was published in Spring 2011 Baseball Research Journal

The Illinois-Indiana-Iowa baseball league started its ninth consecutive season of play in May 1909. While the league was better known then as the Three-I or Three-Eye league, the name was actually a misnomer. The eight teams in the league that year were located only in Illinois and Iowa. (This would not be the last time that the Three-I league would pretend to be what it was not.) Classified at the time as a class B league, the Three-I in 1909 would be comparable to high-A or double-A ball today. The Bloomington Bloomer club began 1909 at a disadvantage compared to the league’s other teams.

While six of the eight teams started spring training the week of March 29, and the Cedar Rapids Rabbits opened their practices the following week, Bloomington was forced to wait until April 13 to call their players into action because their playing grounds were undergoing a major renovation and work could not be completed before April 10. Even when the Bloomers reported April 13, the Bloomington Pantagraph noted that “players will work out at the Armory until the grounds are in shape to play,” indicating that renovations took longer than expected.

To add another wrinkle to an already inauspicious beginning, on Monday, April 12, before the team even held its first practice, the Pantagraph reported “Baseball Co. Needs Money.” Like many small-town teams of the time, the Bloomers were owned by local citizens interested in baseball. The 1909 season brought with it a new group of local investors. As a welcome gesture, the old association members donated $100. The coffers, however, were not as full as the new management had hoped. Expecting to find their share of league revenues approximately $400 in the treasury, the owners instead found a $150 league assessment fee. Coupled with pre-season expenses, the cost of renovations, and a limited influx of revenue, the organization was $1,475 in debt.

Fifty miles south in Decatur, Illinois, a very similar circumstance faced the Decatur Commodores, another Three-I club trying to secure its professional and organizational livelihood. After a disastrous 1908 season in which club owners ended with a net loss of $4,500, provisions were made to transfer a majority of the team’s stock in the Decatur Baseball Association to a local resident, Dr. C.F. Childs. The first order of business for Childs was to recruit a number of fellow Decatur baseball enthusiasts to act as board members and stir up interest in the community. Faced with the substantial financial deficit from the previous year, Childs made a number of moves, including selling $3,300 worth of players, which allowed him to pay off his debt.

Childs and his magnate pals in Decatur then found $4,000 to build a new ballpark and spent another $1,000 to replace players sold. In addition, the May 2 Decatur Daily Herald reported that the owners “dug liberally for the necessary expenses of training.” While the Commodores were able to begin practice earlier than the Bloomers, the weather was an impediment during the first two weeks of April for both teams, and hosting exhibition games was difficult.

The spring of 1909 was very wet, which made it difficult to play any spring training games. Several practice scrimmages were cancelled due to both the wet conditions and the difficulty and expense of holding such a game. Teams scrambled to find dry ground, and when a field was found, the games usually pitted Three-I clubs against local amateurs.

The spring of 1909 was very wet, which made it difficult to play any spring training games. Several practice scrimmages were cancelled due to both the wet conditions and the difficulty and expense of holding such a game. Teams scrambled to find dry ground, and when a field was found, the games usually pitted Three-I clubs against local amateurs.

The Bloomington Bloomers were one club that took advantage of its immediate surroundings. Bloomington was home to Illinois Wesleyan University, a small liberal arts college with a baseball program. As soon as dry grounds could be produced, Illinois Wesleyan signed up, providing the opportunity to scrimmage without the cost of traveling or pressure of making box-office receipts to help offset traveling expenses. Friday, April 16, the Bloomers were playing their first exhibition game of the 1909 season against Illinois Wesleyan at the school’s Wilder Field. The minor leaguers bested the collegians 6–4. The Bloomers agreed to a rematch the next day at the newly renovated South Side Grounds. Not surprisingly, spring showers canceled the game.

The Bloomers’ first “official” exhibition game of the season was to be against the Burlington, Iowa team of the Central Association on Sunday, April 18. The 3:00 P.M. game was billed as “opening season—Grand Dedication Game.” The game was to mark the dedication of the renovated ballpark under its new management. Infield admission was twenty-five cents and grandstand seats lining the outfield were free.

Burlington, previously in Decatur for an exhibition game with the Commodores, boarded the 11:00 A.M. Interurban train to Bloomington, providing plenty of time to warm up. Unfortunately, the weather again did not cooperate and Burlington boarded the 4:00 P.M. train back to Decatur. Burlington manager Ned Egan was sorely disappointed in the cancellation, saying that this would be the last time he would play exhibition games with other Three-I clubs because of high costs. The dedication game’s postponement also hit the Bloomers hard; the club was relying on gate receipts to alleviate its financial crisis.

On Wednesday, April, 21 Bloomington was able to scrape enough money together to send a group of fourteen Bloomers, along with Manager William McNamara, to Kewanee, Illinois for four exhibition games with the town’s Central Association team. Manager McNamara had left the “regulars” home to practice. The manager of the Kewanee squad was Bloomington-Normal native William Connors, who had managed the Bloomers in 1908. Connors actually rode the train with the Bloomers, as he had recently returned home to take care of personal matters. As fate would have it, the first two games of the trip were canceled due to—yes—uncooperative weather.

On Sunday, April 25, Bloomington played what the local papers dubbed its inaugural exhibition game at newly renovated South Side Grounds, beating Three-I rival the Peoria Distillers, 8–3. On the same day another squad of Bloomers traveled to Decatur to play the Commodores. The game remained tied 1–1 until the last of the ninth when Decatur pushed across the winning run.

Lack of funds and the fear of further wet weather forced the Bloomers to cancel their next scheduled exhibition games in Quincy and Jacksonville. With twelve days left before opening day, the financially strapped Bloomers had only two more exhibition games scheduled (both at home). On Thursday, April 29, the Bloomers faced the collegians of IWU at South Side Grounds and won convincingly, 5–0. The last scheduled exhibition game of the season was with Decatur on Sunday, May 2, in Bloomington. Unfortunately, this game, too, had to be canceled because the grounds crew was unable to get the field in shape following a circus held there earlier in the week. Decatur was also unable to host as there was a scheduling conflict with their field. At the last minute, however, a game with the Springfield Senators was secured in Springfield. Bloomington lost to the Senators 9–6.

The Decatur Commodores’ two-week head start on spring training allowed the club to play a good amount of exhibition games, as they found enough dry grounds and willing opponents. Like Bloomington, the Decatur ball club also benefited from having a local liberal arts college in the city limits. On April 3 the Commodores faced off against Millikin University. It was not much of a game, as Decatur handled the college boys 20–6.

Decatur was also home to an independent ball team called the Decatur Blues. This happenstance afforded the Commodores the chance to schedule additional games at little to no cost. On April 4, a day after crushing Millikin, the Commodores welcomed the Blues to League Park and won a 6–5 squeaker. Over the next week the Commodores practiced when weather allowed and held intra-squad scrimmages dividing into “Jakes,” named after team member Albert “Beany”

Jacobson, and “Moores,” named after team manager Fred Moore.

By April 10, the Commodores saw their first real exhibition opponent when the Hannibal Cannibals from Missouri arrived at League Park. The Commodores escaped with a 3–1 victory and the Decatur Daily Herald ramped up its coverage of the team. Over the next several days Decatur hosted games with minor league teams from Appleton, Wisconsin; Buffalo, New York; Burlington, Iowa; and Jacksonville, Illinois. On April 20, Fred Moore loaded up his team for an extended road trip which included Jacksonville, Illinois; Hannibal, Missouri; Burlington, Iowa; and Pekin, Illinois. Even though rain and cold weather was a problem throughout April, the Commodores squeezed in at least 16 pre-season games. According to the Daily Herald, which published simple batting statistics for its nine main players, Otto Burns led the club with a .319 average. While the newspaper downplayed the successful averages it did go on to note:

Decatur has nothing to worry about in the makeup of its team. It has the fielders, the batters, and the pitching staff and it has the manager to get everything out of them. More than that it has a club back of him that has already shown its intention of strengthening any weak point that develops with the idea of giving Decatur fans the best ball team they ever had.

Although Decatur fared well in getting in their games, a lack of exhibition games was a problem throughout the league. The home newspaper of league champion Springfield Senators, the Illinois State Journal, noted on May 2, “This was the most disheartening training season in history, not a team in the circuit has been able to make feed money and have been hustling to secure money to meet expenses.”

Regardless of how little baseball was played, the respective newspapers of each city still stirred up controversy. On April 3, the Decatur Daily Review reported that the Commodores had been chosen over the Bloomington Bloomers to play the May 2 dedication game at Pekin Park. Bloomington thought it had a signed contract in hand from the Pekin manager, Doug Jeffries, and as a result were threatening to “set the law dogs on Jeffries.” Decatur probably thought the dedication game at Pekin was rightfully theirs, as Jeffries was a respected former outfielder with the Commodores.

Regardless of how little baseball was played, the respective newspapers of each city still stirred up controversy. On April 3, the Decatur Daily Review reported that the Commodores had been chosen over the Bloomington Bloomers to play the May 2 dedication game at Pekin Park. Bloomington thought it had a signed contract in hand from the Pekin manager, Doug Jeffries, and as a result were threatening to “set the law dogs on Jeffries.” Decatur probably thought the dedication game at Pekin was rightfully theirs, as Jeffries was a respected former outfielder with the Commodores.

Bloomington did, in fact, have the contract (as the Decatur newspaper admitted on April 10), but the unwanted attention pressured the Bloomers to promise to send their top players. Written barbs between Bloomington and Decatur papers appeared quite frequently not only before the season but as the season progressed. The rivalry between the cities was obvious and was no subdued matter. It was not uncommon for a sarcastic comment to appear in “Glints from the Diamond” or “Brevities of Sport” wishing luck to the losing team or telling fans to be thankful that they were not experiencing the misfortunes of the other club.

By April 29 the rivalry got a little more heated. The Decatur Daily Herald took exception to comments made by the Bloomington sports reporter about their beloved Commies in a series of articles that appeared in a Springfield, Illinois publication. The Bloomington reporter apparently referred to Decatur players as “untried and inexperienced and even unfit for [a] high school league.” The Daily Herald reporter, in turn, ended his rebuttal column with, “But what’s the use of enumerating. We might not expect anything more from a Bloomington man.”

Not lost in all the give-and-take between the newspapers was the fact that Bloomington canceled its commitment to the May 2 grand dedication game at Pekin. Decatur gladly stepped in to fill the spot. Encounters like these undeniably added to the rivalry between the cities and their respective clubs.

The Three-I League’s fans and players eagerly anticipated opening day. On Thursday, May 6, Bloomington’s baseball bugs were prepared. The Bloomers and their opponent, the Peoria Distillers, paraded through downtown Bloomington in automobiles supplied by the Automobile Club of Bloomington. Fred Ashton’s fifteen-piece band accompanied them on the parade route, which started at the Hills Hotel and proceeded through the downtown square and to the newly renovated South Side Grounds. Prior to the game, newly elected Mayor Richard Carlock made an impassioned speech about the importance of baseball to the community.

The rains held off, and opening day in Bloomington appeared to be a big success. (In fact, the weatherman cooperated in all Three-I cities and all scheduled games were played.) Bloomington’s opening-day attendance was reported as 1,491, slightly less than the previous year’s opening crowd (1,911) but significantly more than the 880 who had showed up in 1907. The Bloomers lost, 3–2 in 10 innings to Peoria. The next time the two clubs took the field, they also took 10 innings to decide matters, and again Bloomington lost, this time 4–2. Ed Clark went the distance for Bloomington in the second game.

Bloomington’s first two games were an indication of things to come—losing close games that took more than nine innings. The Bloomers started slowly, losing their first four games and nine of their first 14, and were soon in the cellar of the eight-team league.

The Decatur Commodores had the privilege of opening their season on the road against the defending league champion Springfield Senators. Opening day in the state’s capital city, like that in most other Three-I cities, featured a parade—this one beginning at the St. Nicholas Hotel an hour before the game. Led by the Watch Factory band and followed by 300 representatives of the Chamber of Commerce, both teams’ players paraded through the business district to League Park. A special carriage took Mayor Jon Schnepp to the ball field to throw out the ceremonial first pitch.

Fourteen hundred fans braved cold and windy conditions to fill the seats and were rewarded with an 8–6 win from Manager Dick Smith and his Senators, although the visiting Commodores perhaps made the game most memorable.

In the bottom of the fifth inning with two outs and Springfield up 7–2, Decatur catcher Bert Fisher became upset with umpire Burke and in a fit of anger threw the ball against the backstop as a protest and muttered a few choice words. Umpire Burke immediately threw him out of the game.

Moments later, Blauser, Springfield’s shortstop, scored on a passed ball that looked suspicious to Decatur manager/second baseman Moore, who chargedin from his position at second to protest umpire Burke’s ruling. According to the Illinois State Journal, Moore rushed in, waved his arms wildly, and talked at random, finally falling to the ground in a failed attempt to be funny. An unamused Burke also threw him out of the game and then out of the park altogether, but Moore refused to leave, necessitating that a Springfield police officer escort him out.

Decatur’s opening game presaged their season as well, marked as it was by controversial calls, managerial protests, and the need for substitutions.

While extra inning games, controversial calls, and rain dotted Bloomers and Commodores baseball that summer, a particular extra-inning game between these two teams on May 31 particularly stands out.

Sunday, May 30, 1909, was Memorial Day. Like all other Three-I teams, the Bloomington Bloomers and the Decatur Commodores (often shortened to Commies) were set to play a holiday doubleheader. The league office had scheduled morning-afternoon twin bills to double the gate receipts. Bloomington, however, was given special dispensation to hold a traditional afternoon doubleheader. Bloomington had made the case to league President M.H. Sexton that the teams stood a better chance to attract a larger crowd with an afternoon doubleheader. This was a key matter because at the time, all gate receipts for Memorial Day ball games were pooled collectively and dispensed evenly among all the teams in the Three-I League. Memorial Day games drew far larger crowds than typical ball games, and splitting the money evenly was nearly essential, considering most teams’ financial struggles. President Sexton accepted the overture, claiming that “by playing two afternoon games the fans will get a double run for their money.” The first game of the afternoon doubleheader between the Bloomers and Commodores began at 2:00 P.M.

Neither team was in particularly good shape at the time. While Decatur was able to claim a 12–10 record, the Bloomers had just lost two in a row to Springfield and limped in at a less than respectable 7–14. Uglier than the records were the teams’ physical (and in one case emotional) well-being. Both teams’ pitching corps had been exhausted. The Commodores had just suspended one of their best twirlers, “Beany” Jacobson, for violating training rules on the western trip. The disciplinary move caused a rift between manager Fred Moore and team president Doc Childs. Moore soon resigned as manager, forfeiting his responsibilities to make player personnel decisions but as field captain would still make all on-field game related decisions. The good news for the Commodores was that first baseman Sam Foster was reinstated after serving his suspension for striking an umpire in Dubuque.

The Bloomers, on the other hand, had just replenished their pitching by picking up William Miller, on loan from Springfield, and William Steen, a free agent who chose to sign with the struggling Bloomers. Unfortunately, neither man would be available for Memorial Day duty. Catcher Nig Langdon, however, had just returned to Bloomington and would be with the team for the Memorial Day matchup.

For Game One, Bloomington manager McNamara gave the starting mound assignment to Ed Clark, who had struggled early on but also suffered from hard luck. He was just 1–4, but each of his first five games of the season had been decided by two runs or fewer.

Fred Moore was so desperate for pitching that he sent backup infielder/outfielder Otto Burns to the “pitcher’s box.” Burns had never pitched professionally and not taken the hill competitively since his youth in Ohio. It rained May 30 in Bloomington and the grounds were soggy. The sun did appear briefly just after noon, giving some hope of decent weather. At precisely 2:00 P.M., in front of 1,200 onlookers, Umpire Clarke called the game into action. The field was muddy from the morning showers, but these games had to be played for financial reasons. Scarcely had the first pitch been thrown when a light drizzle began.

In the home first, Decatur second baseman Moore dropped Frank Long’s grounder, allowing him to safely reach first base. The speedy Long immediately stole second. Joe Keenan and George Cutshaw were unable to advance Long any further, but the cleanup hitter, first baseman Frank Melchior, “smash[ed] a hit through John Barkwell” at third, allowing Long to score the first run of the game.

Decatur would tie the score in the third when Otto Burns led off with a single to right and advanced to second on Moore’s sacrifice. Barkwell doubled to left, plating Burns.

The gentle rain persisted until the fifth inning when the drops became larger, forcing players off the field and the fans to run for the cover of the grandstand. After 30 minutes play resumed, and both coaches decided to keep their starting pitchers in the game.

Neither team mustered much offense, although the Commies filled the bases in the seventh with one out but could not score.

The game—just the first in a doubleheader—progressed to the thirteenth inning. In the top of the frame, Decatur’s Jesse Ruby walked. Bloomington’s Clark, still on the hill, plunked Barkwell and walked Sam Foster. The Commodores now had the bases loaded with nobody out. Moore called for the squeeze play, but Jenkins bunted right to the pitcher, Clark, who forced Ruby at the plate. With the bases still packed, Cote hit a tailor-made double play ball that got the Bloomers out of the inning. With the threat averted the Bloomers and the Commies proceeded to play 12 more innings of no-run baseball.

More than four hours had passed and it was well beyond 6:00 P.M. The rain continued to fall soaking the players and making the field conditions questionable. Infielders and base runners were slowed by the mud caking on their cleats and the outfielders remained cautious of slippery footing.

But the rain did not keep the fans away, nor send home many of the ones already there. As the game progressed into innings 20 and beyond, word had spread through the community that something historic was taking place at South Side Grounds. Few fans had left and more were undoubtedly attracted to the possibility of history being made.

Adding to the excitement of the contest was whether or not the game would be allowed to officially end with a winner. Not only were the teams battling to a 1–1 tie, the continued rain made playing conditions border on dangerous and the dark weather coupled with late afternoon skies made it difficult to see. On top of the physical limitations, Decatur was pressed to catch the last train of the night which left within the next half hour.

Twenty-five innings had elapsed, and all eighteen players who started the game were still fighting, including both starting pitchers. Bloomers pitcher Clark still appeared strong, as Jenkins and Cote of Decatur opened the twenty-sixth by grounding to Roy Snyder at short. The next batter, Bert Fisher, took the first pitch for a strike then hit a high, but easy, pop foul down the first base line. What would appear to be a sure third out landed harmlessly between catcher Langdon and first baseman Melchior. With an 0–2 count and a second chance to swing the bat, Fisher stepped back in the batter’s box. On the next pitch, Clark threw one inside which hit Fisher in the ribs; this was Clark’s third hit batter of the game.

Decatur second baseman Mark Purtell dug in. On the first pitch he saw, he scorched a line drive over Melchior’s head at first which rolled all the way to the scoreboard. By the time Bloomington right fielder Jim Novacek retrieved the ball, Fisher had scored and Purtell was standing on third base.

Manager McNamara of the Bloomers came storming out of the dugout protesting that Purtell had “cut” second base. The umpire agreed with McNamara that Purtell had, in fact, missed second and proceeded to call him out, ending the inning. McNamara was still not satisfied. He argued that Fisher had not yet crossed home plate at the time that Purtell had approached second base, and therefore the run should not count. The umpire disagreed, awarding Decatur the run, claiming that Fisher had already crossed home. In the span of three pitches a foul ball had been misplayed, a batter hit in the ribs, and a pitch driven for a run-scoring “single”—all this activity after 26 innings of baseball, with the last 23 innings being scoreless. Someone had finally crossed the plate, albeit under protest. Decatur was in the lead 2–1.

The Bloomers bats fell silent in the bottom of the twenty-sixth, and with two outs, manager McNamara installed himself as a pinch-hitter. It was the first and only substitution of the game. The strategy did not pay off, as McNamara was easily retired to end the game. Although Bloomington would protest the game, the Commodores left South Side Grounds victorious. Not surprisingly the second game of the doubleheader was called off, due to darkness and the visitors’ need to catch the night’s last train home.

A rather large crowd, estimated at more than 1,000, had gathered outside the Decatur Daily Herald offices, where recaps of the action were posted. Once the final score was announced, the crowd erupted and moved to the Transfer House to welcome the team home. From start to finish the game had taken five hours: four hours, 30 minutes of actual baseball and 30 minutes of rain delay, with only the one substitution. Clark of Bloomington and Burns of Decatur pitched complete games.

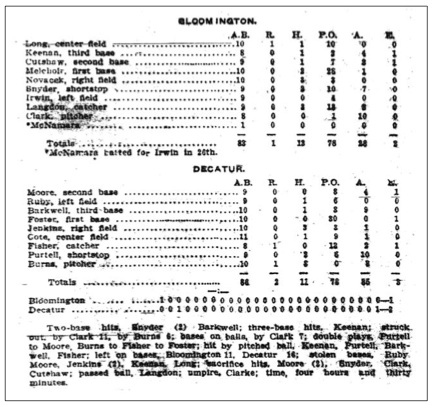

Over 26 innings Ed Clark faced 98 Commodore batters, allowing two runs, eleven hits, and six walks, and hitting three batters. He was so dominant that he only ceded multiple hits in one inning (the third when Decatur pushed across their first score). His counterpart, Burns, pitching his first professional game, faced 88 Bloomers, allowing 13 hits and one walk and plunking one batter. Bloomington committed two errors and stranded 11 men, while Decatur committed three errors and left 16 runners on. (Oddly, the walk Burns issued wasn’t recognized until the June 2, 1909 Pantagraph. The Bloomington scorer was either caught up in the excitement of the game or overcome by its length and neglected to record a free pass given to Nig Langdon in the eighteenth inning, a tactical move which loaded the bases and allowed a force out.)

Defensively the game was well played with both the Decatur and Bloomington papers reporting a number of fine catches and throws. Decatur’s second baseman, Moore, first baseman Foster, and catcher Fisher each committed one error. On the Bloomers’ side, second baseman George Cutshaw and third baseman Joe Keenan were guilty of blunders. Both first basemen were kept busy, claiming 58 putouts between them.

Decatur pitcher Burns and right fielder Jenkins led the team with three hits each, while Bloomington’s catcher Langdon and right fielder Novacek also paced their club with three hits. Decatur’s scorekeeper credited the game’s hero, Purtell, with two hits, one being the game-winning triple, while Bloomington’s scorebook also credited Purtell with two hits but—correctly—credited him only with singles.

This marathon game was, at the time, the longest professional baseball game played in innings, surpassing the previous high count of 25 innings on July 18, 1891 in Devils Lake, North Dakota, when the Grand Forks Black Stockings and Fargo Red Stockings jousted to a scoreless tie.

The headlines in the Pantagraph the next day read “Bloomers Lose Longest Game.” The Decatur Daily Review posted the entire inning-by-inning score across the top of the page with the number one posted in the bottom of the first and the top of the third and 26th innings, with 49 zeros filling the rest. The Daily Herald headlined its story “Decatur Wins Longest Ball Game 2–1 in 26 Innings.” Both cities’ papers dedicated a great deal of space to the game, and rightfully so as this was a record-breaking event. While all newspapers had essentially the same stories, the demeanors were certainly different.

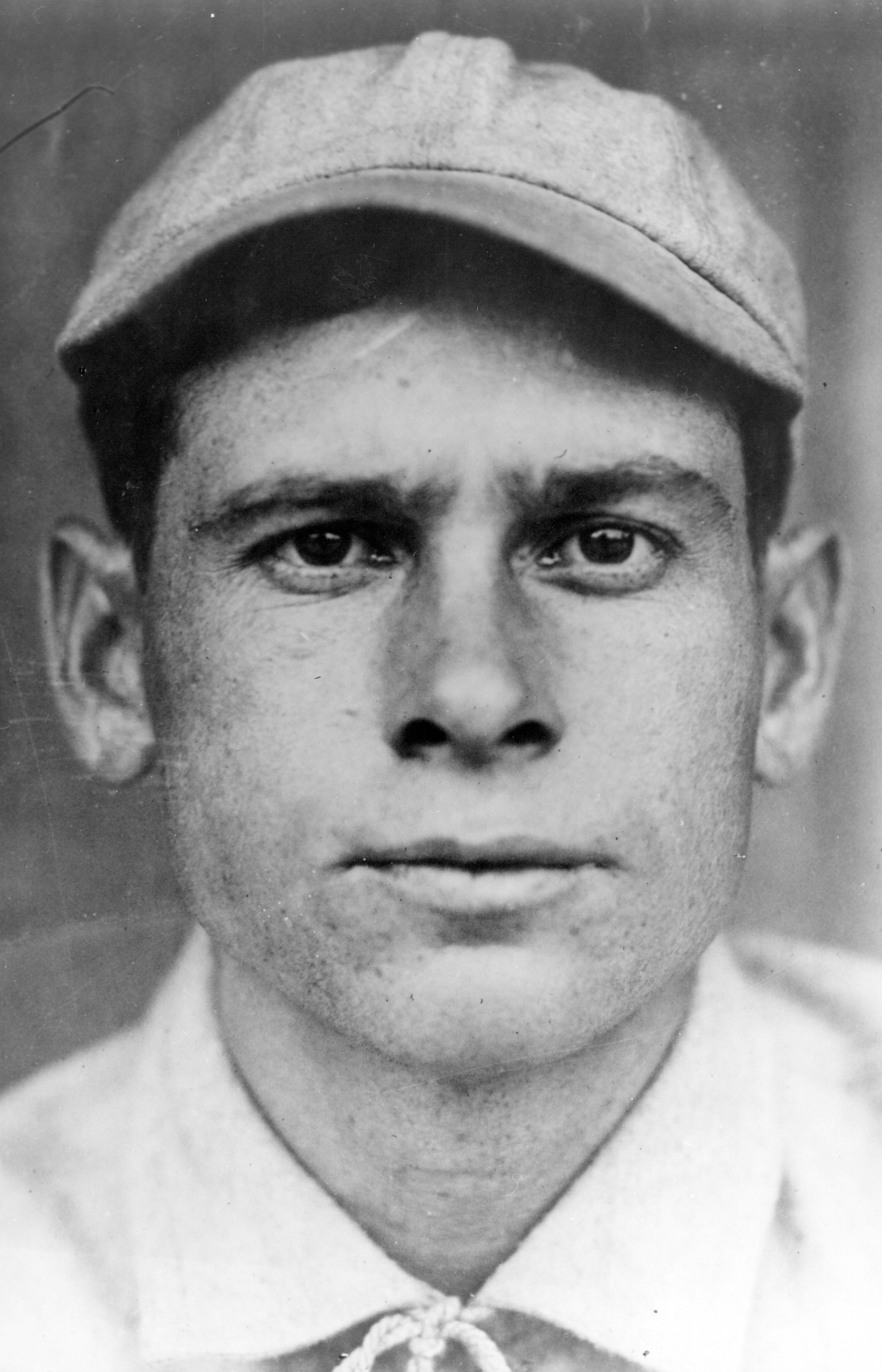

Decatur papers ran pictures of their heroes: “Little” Mark Purtell, Fred Moore, and, of course pitching ace Otto Burns. The paper provided extended detailed coverage of the game and lauded the perseverance of the ball club in holding strong and scrapping to victory. The paper also published photos of the crowds that had gathered the night before outside the paper’s offices to keep track of the game courtesy of the news wire. The excited crowd spilled over the curbs and into the street as fans followed the game. Of course, mention was also made of the “unsportsmanlike” protest Bloomington had made regarding the controversial run.

While the Bloomington Pantagraph also featured extended coverage of the game, the tone was more somber. The Bloomers fought until the end, it was written, but just didn’t have enough when it counted. Pictures of Ed Clark and manager William McNamara graced the pages of the sports section.

The next day, at the Sherman House in Chicago, where each Three-I team president had convened to discuss payroll and roster sizes, they read about the Bloomers’ and Commodores’ exploits like the rest of the country. From New York to California and every where in between, the “marathon

game” had been recounted and recognized as the longest official professional baseball match. As the day’s first order of business, President Sexton made sure to congratulate the representatives of both clubs and recognize the attention that this distinctive game had brought to their circuit. The fact that the longest baseball game played now belonged to the Three-I League was not lost on the representatives at the meeting. In a moment of levity, President Kinsella of the Springfield Senators publicly offered the Bloomington management a large sum if they would send their team to Springfield and pull off a similar stunt.

Later in the evening, Decatur president Doc Childs received a telegram asking for the price on pitcher Otto Burns for immediate delivery. The telegram was signed “Charles Comiskey, manager, Chicago White Sox.” Childs was said to have smiled as he read the message, knowing it was a practical joke. It was later revealed that the prankster was the president of the Bloomington club.

The nostalgic game made for a more relaxed meeting and might help to explain how the Three-I magnates so quickly agreed on new roster and salary limits. The news out of the Sherman House on June 2 was that league teams would be allowed to now carry 14 men, one more than previous, and that the salary limit had been increased to $1,750.

Even if they had wanted to, neither team could escape attention for long. On Tuesday morning, two days after the record-breaking game, the Bloomers boarded the train to start their next road trip. First stop, Decatur, Illinois, to play the Commies! The marathon game of the previous day undoubtedly raised interest, as attendance was estimated at 1,500 for the afternoon game. Among the attendees were 500 women who were each presented with a special carnation to commemorate the previous day’s game. Before the action could begin, Otto Burns was presented a bouquet of roses in recognition of his work on the slab. Bloomington won this game, 3–2, in nine innings with no late dramatics. Newspapers from both cities were quick to point out that both teams showed the effects from the previous day’s game, noting listless efforts and sleepy play.

When the Bloomers returned home from their road trip on June 6, arrangements had been made by the local community to recognize the club for its participation in the record-setting game. Baseball magnate E.E. Donnelly delivered a brief speech before the game and a group of appreciative and enthusiastic fans presented the team with a floral emblem containing what the local paper called the cabalistic number 26 in the center. Unfortunately, the Bloomers failed to play up to the expectations and lost to Rock Island. Coincidentally, on the same day Bloomington was recognized for their part in the historic game, Otto Burns—who had beaten them a week earlier—pitched his second professional game, winning 4–3 in ten innings.

Shortly after the historic game, Bloomington’s Clark was called home to Chicago to take care of his ailing mother, the Pantagraph reported. He did not return to the team until June 7, when he promptly returned to the pitcher’s box. In his first start after the marathon game, Clark lasted only four innings; the lowly Cedar Rapids Rabbits tagged him for six runs. While one could assume that he was ineffective due to his recent workload, it also must be noted that early in the game, he had been hit in the pitching arm by a batted ball. Oddly, the umpire for Ed Clark’s return game was Clarke, the same umpire from the extra-inning affair. And as fate would have it, the catcher for the Cedar Rapids team was called out after an apparent home run for—what else?—failing to touch second base.

Ed Clark did not pitch again for eight days. When he returned to the hill, it was once again for no ordinary game. On June 15, Clark pitched a complete-game win—this time 15 innings—over the Peoria Distillers. Clark faced 58 batters in the 15 innings and went 2-for-7 at the plate. The game lasted all of three hours and was, interestingly, umpired again by Clarke. In two of three starts, Ed Clark pitched a combined 41 innings and faced 156 batters. It’s no surprise that the Pantagraph labeled him “The Long Distance Hurler.”

Over the following weeks the two teams received more notoriety as other newspapers around the county picked up on the novelty of the 26-inning game and local citizens did what they could to keep the memory of the event alive. One citizen just outside of Bloomington, sign painter North Livingston, reproduced the entire box score of the game, including player names and positions, on the blackboard at the Metropole.

Much of the outside attention was acknowledged in various papers’ sports sections under headings like “Glints of the Game” or “Brevities of Sport.” On June 10, the Pantagraph noted, “Man returns from visit out east proclaiming 26-inning contest put Bloomington on the map.” Similarly, on June 18 a Los Angeles newspaper was cited as giving the 26-inning game “big space.” The acknowledgment that their game meant something outside their communities was important to both Decatur and Bloomington.

Nearly lost and forgotten in the publicity of the record-breaking game was the protest filed by the Bloomers. On June 16 the protest was finally resolved.

The following day’s papers reported that President Sexton announced the awarding of the 26-inning game to the Commodores. It is said that after careful consideration, Sexton came to the conclusion that the Commodores had won the game “fairly and squarely.” Of course reporters from both cities had a slightly different understanding of what “fairly and squarely” meant, but both cities and teams had accepted the outcome. On Monday, June 7, the Bloomers lost to last-place Cedar Rapids, 9–4. Following the game, William McNamara resigned as manager and left the team. According to news reports, McNamara had attempted to quit at the end of May but was dissuaded by the directors. At the time of his resignation Bloomington was 9–18.

Just two days later, the Cedar Rapids Rabbits were in town to play the Bloomers and had just lost their catcher to injury. McNamara accepted the invitation to play against his former team for the day and came through with a double. In another odd turn of events, McNamara replaced Bert Fisher in the Decatur lineup and finished the season with the Commies.

The Decatur Daily Herald was reporting by June 5 that Fred Moore would soon be released. The club finally parted ways with its second baseman on July 16. Third baseman Johnny Barkwell took charge. The Bloomers began to play better ball and finished the season in fourth place (among eight teams) at 70–67. The Commodores couldn’t keep pace and finished seventh with a 63–73 record. The Bloomers won 10 of 19 games between the two clubs.

Otto Burns remained in the Decatur rotation for the rest of the season pitching soundly for his team. Ed Clark also remained in the starting rotation for the Bloomers until late August, when his struggles were too badly hurting the club. According to the Pantagraph, he was loaned to the Central Association’s Kewanee Boilermakers. Clark did rejoin the Bloomers late in the season and pitched in the season’s penultimate game. He hung around after the season to collect a few extra dollars by barnstorming around central Illinois with some other Bloomers.

Mark Purtell, hero of the marathon game, engraved his name in the Three-I record books at the end of the 1909 season, but not positively. The man who had the game-winning triple, or single, set an all-time low in batting average for regular players. His .135 season average still stood as the record of hitting futility at the end of the Three-I league’s existence nearly five decades later. Mark never reached the heights of his brother Billy, who spent five years in the major leagues—including 1909 with the Chicago White Sox.

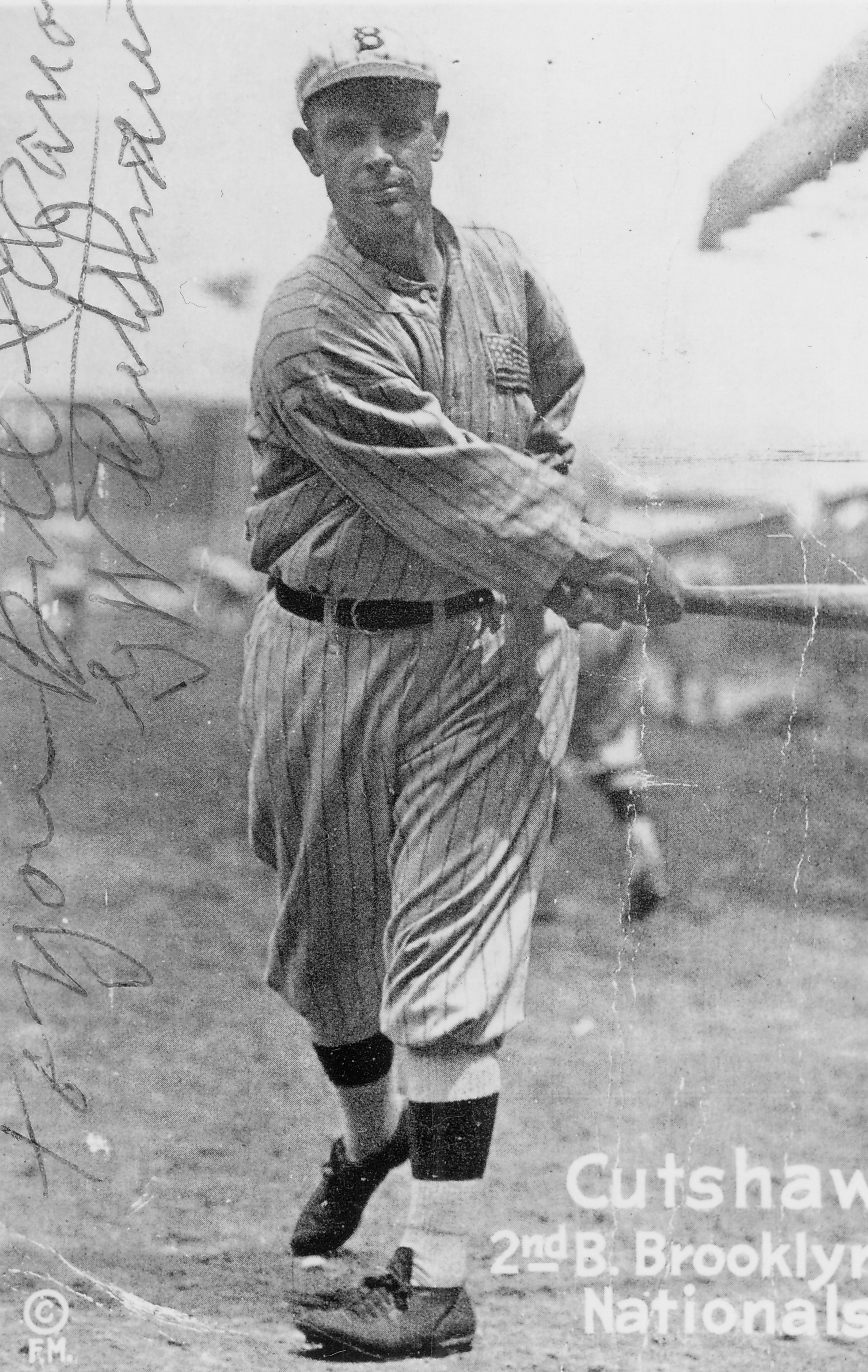

George Cutshaw, Bloomington’s second sacker, experienced the most success of all the players in the historic game. Cutshaw broke into major league baseball in 1912 with Brooklyn and played there for six seasons. He also spent four seasons in Pittsburgh and finished his career with two seasons in Detroit. During his twelve-year career, he collected 1,487 hits, amassed a .265 batting average, and swiped 271 bases. For 57 years, the Bloomers and Commodores held the distinction of playing the longest completed professional ballgame in the United States (the Class C Mexican Center League featured a 27-inning game in 1960). Not until 1966, when Miami needed 29 innings to defeat St. Petersburg in a Florida State League matchup, did the Three-I League lose hold on the history books. In 1981, the Pawtucket PawSox and Rochester Redwings played a 33-inning game in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. The game actually started on April 18, 1981, when 32 innings were played, and finished with the deciding inning on June 23, 1981.

What was a great sense of pride for two Illinois cities has now been lost to history. The Three-I League has folded and all players, fans, umpires, and writers associated with the marathon game have long since passed on. Accounts of the game are posted in local newspapers only when on a noteworthy anniversary.

Even descriptions of the game are severely limited. We may find mention of the 26-inning contest in newspapers under the headings “Almanac,” “On This Date,” or “Yesteryears.” But for five decades, two small farming towns in Central Illinois held a record that brought their teams, cities, and league a great deal of notoriety. For fifty years those teams shared the spotlight, remembered their exploits together, and laid their claim to baseball fame.

SOURCES

This essay called on information mainly culled from three Illinois newspapers: the Bloomington Pantagraph, the Decatur Daily Herald, and the Springfield (Illinois) State Journal. These papers provided information in editions printed between April 3, 1909 and July 17, 1909. In addition, the ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, edited by Pete Palmer and Gary Gillette and published in 2004 by Barnes & Noble, was used.