The Milwaukee Brewers Move to St. Louis and Become the Browns in 1902

This article was written by Dennis Pajot

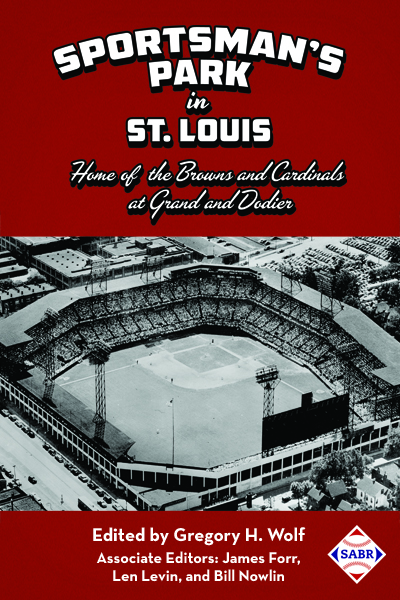

This article was published in Sportsman’s Park essays

In the fall of 1893, a new Western League was formed with Milwaukee as a charter member. The first (and only) president of the Milwaukee Brewers was Matthew R. Killilea, born in the town of Poygan, Wisconsin. An 1891 graduate of the University of Wisconsin, Killilea was thereafter appointed assistant district attorney in Milwaukee County, but could not serve as he had not yet practiced law the required time. In 1894 he was an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for the Wisconsin State Assembly from Milwaukee. He was a lifelong bachelor. It was said that Killilea “is a young man of fine, natural abilities, good attainments, and has a promising future before him.”1

In the fall of 1893, a new Western League was formed with Milwaukee as a charter member. The first (and only) president of the Milwaukee Brewers was Matthew R. Killilea, born in the town of Poygan, Wisconsin. An 1891 graduate of the University of Wisconsin, Killilea was thereafter appointed assistant district attorney in Milwaukee County, but could not serve as he had not yet practiced law the required time. In 1894 he was an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for the Wisconsin State Assembly from Milwaukee. He was a lifelong bachelor. It was said that Killilea “is a young man of fine, natural abilities, good attainments, and has a promising future before him.”1

Managed by Charlie Cushman in 1894, the 47-74 Brewers finished in last place, but president Killilea still claimed an $800 profit for the season.2 That fall a new major-league was rumored in the planning stage. Slated for inclusion in this new circuit was a Milwaukee franchise to be headed by Milwaukee businessman Harry Quin, owner of Athletic Park where the Western League Brewers played. Viewing the new league talk as merely a gambit by Quin to raise their rent, the Brewers promptly relocated to new grounds on Milwaukee’s far north side at 16th and Lloyd.3

Under a new field manager, the Brewers struggled to a 57-66 mark in 1895, but ended up approximately $10,000 ahead financially.4 Then during the offseason, Fred Gross, owner of a local meat-packing company, who would later figure prominently in the shift of the Milwaukee club to St. Louis, was appointed club secretary.5 A midseason change of managers did not help the sixth-place Brewers in 1896. On the financial front, officials claimed the club broke even and would have made $20,000 if it were not for a streetcar strike.6 But this is doubtful. Ten days before the season ended it was rumored that the club was for sale, and while directors denied it, they admitted that the club would lose about $2,500. Nevertheless, offers to buy the Brewers, including a $9,000 bid by the Milwaukee Sentinel and a $12,000 offer by an anonymous Milwaukee businessman, were rejected. As far as president Killilea was concerned, the club was not for sale at any price (even though three losing seasons in the Western League had apparently depreciated its value).7

In 1897 management signed Connie Mack to manage the Brewers for $3,000, the highest salary ever given a Milwaukee manager to date.8 Mack, recently dismissed after two-plus seasons as player-manager with the Pittsburgh Pirates, was given free rein and began to build a winner. His first Brewers club finished in fourth place with an 84-51 record and led the Western League in attendance. In the postseason estimation of the Milwaukee Journal, the club made a handsome profit of $22,100.9 Mack, also a part-owner of the club, was “$2,000 richer than he would have been if he had remained in the big leagues last season.”10 The next season, Mack led the Brewers to a third-place (82-57) finish, while the club made another $20,000.11 But when the 1899 team finished a distant sixth, club management came in for criticism, with one local writer complaining: “It looks as though the present team were run for revenue and revenue only. … The popular idea is that the Brewers are run on a very cheap basis.”12

In 1899 there was renewed talk of a new major league, this time a revived American Association, promoted by Chris von der Ahe, recently dispossessed of his St. Louis National League franchise; St. Louis promoter George Schaefer; and Albert Spink of the St. Louis Dispatch. In September an organizational meeting was held in Chicago, with 10 cities, including Milwaukee, represented by interested baseball men. The Milwaukee representatives were sporting-goods business owner Harry D. Quin and clothing store owner (and city alderman) Charles Havenor.13 Western League President Ban Johnson took advantage of the proposed new league to seek expanded draft protection for his own league and, more importantly, to place a team in Chicago.14 He also changed the name of his circuit to the expansive-sounding American League. It was observed that “this shrewd and unexpected move is designated to deprive the proposed new rival American Association of the benefits of a traditional title, without infringing upon the League’s rights in the matter; to remove the ex-Western League from its hampering sectional basis, and to place it in the position to become nationally known.”15 Soon, backers dropped out of the American Association, and it was dead by February.16 But once the AA threat was gone, the National League began to renege on promises made to the new AL, including refusing it permission to move a club into Chicago.17

Both the National League and the American League prepared for war. For the 1900 season, the formerly 12-club NL contracted to an eight-team league. This, in turn, afforded the AL the opportunity to put a team in abandoned territories like Cleveland. Soon thereafter, the National League permitted the American League to enter Chicago under the ownership of Charles Comiskey, and interleague hostilities were avoided – for the time being.18

Now a member of the still-minor American League, the 1900 Milwaukee Brewers played very well under Mack, finishing second, its 79-58 log bettered only by the champion (82-53) Chicago White Sox.19 Like other AL clubs (with the possible exception of Minneapolis), the Brewers finished in the black, netting approximately $8,000 to $10,000.20

On November 3, 1900, the Milwaukee Baseball Club filed an amendment to its articles of incorporation, increasing the capital stock to $25,000. Principal stockholders Matthew Killilea, Fred Gross, and Connie Mack each held an equal amount of stock.21 Later that month, Killilea stated that he would not object if Mack wished to become part-owner the AL Philadelphia franchise.22 Mack equivocated, but by December The Sporting News reported, and a Philadelphia paper subsequently confirmed, that Mack had sold his stock in the Brewers and purchased an ownership interest in the Philadelphia club.23

On January 28, 1901, the American League reconstituted itself, admitting Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Boston to its ranks, while dropping Indianapolis, Buffalo, Kansas City, and Minneapolis. A 10-year agreement was adopted, with 51 percent of each franchise reportedly being retained by the league with a first option to purchase the club. President Johnson then declared his circuit a major league, breaking off relations with the NL. The two leagues would now go head-to-head against each other.24

Even before the new major got off the ground, there were rumors that the Milwaukee franchise would be transferred to St. Louis. Killilea denied it.25 However, sources claimed that Charles Comiskey had secured old Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, and that Milwaukee would be transferred there if wartime exigencies compelled it.26

Intent on remaining in Milwaukee, club owners signed onetime NL batting champion Hugh Duffy to manage the team. Duffy also reportedly acquired Connie Mack’s stock in the Brewers.27 Working with management to fill out the roster, Duffy liked his club’s prospects, telling a Milwaukee Journal reporter: “We certainly are going to have a crackerjack of a team this season. Our pitching staff is strong, and our infield can’t be beat by any other team in the league. And the outfield will be there with the goods when the time comes.”28 The Sentinel agreed, writing that the Brewers were “exceptionally strong” and Duffy was “one of the brainiest, inside and aggressive players in the country.”29 Oddsmakers disagreed, rating Chicago a 13-to-5 favorite for the AL pennant. Milwaukee’s chances were placed at 15 to 1.30

The Brewers’ foremost problem would be their inability to sign solid National Leaguers. While most other AL clubs signed one or more big-name National Leaguers, the Brewers’ best catch was outfielder John Anderson. Perhaps as a result, the $24,000 Brewers payroll was lower than those of most AL clubs, exceeding only that of Baltimore.31

The season itself started on a sour note. On a belated April 25 Opening Day the Brewers blew a 13-4 final-inning lead when Tigers scored 10 runs to post a 14-13 victory – still a record for ninth-inning comebacks.32 Duffy shuffled his roster throughout the season but could not arrest the club’s slide. The Brewers ended the season where they spent most of it: in last place, with a 48-89 record.33 The Brewers’ final standing was not undeserved, as the Milwaukee Daily News declared that the Brewers team played “the very rottenest ball ever dished up by a major league organization.”34 The team batting average of .261 was the lowest in the league, as was its run total of 641. In the field, the Brewers’ 393 errors were exceeded by only two other teams, while the pitching staff gave up 828 runs, second most in the AL. The only bright spot was the play of John Anderson. In addition to batting .330, Honest John had 190 hits (second in the American League), 46 doubles (second), 99 RBIs (third), 8 home runs (fourth), and 274 total bases (third).35

As reflected in the columns below, the American League was competitive at the gate. As for the Brewers, an article by Ernest Lanigan in The Sporting News placed their biggest crowd at 10,000 for a May 26 game against the Philadelphia Athletics. But only eight Milwaukee home games drew over 5,000, and on 15 dates, attendance dropped below the 1,000 mark. Discouragingly, the last home date of the season, a doubleheader against Chicago, drew a mere 200 fans.36

NATIONAL LEAGUE AMERICAN LEAGUE

Boston 146,502 Boston 289,448

Brooklyn 198,200 Baltimore 141,952

Chicago 205,071 Chicago 354,350

Cincinnati 205,728 Cleveland 131,380

New York 297,650 Detroit 259,430

Philadelphia 234,937 Philadelphia 206,329

Pittsburgh 251,955 Washington 161,661

St. Louis 379,988 Milwaukee 139,034

1,920,031 1,683,58437

Generally, the American League was pronounced a financial success. Ban Johnson claimed that only the Milwaukee club had lost money, with the Milwaukee Sentinel estimating the Brewers’ loss at $5,000.38 But other sources contradicted this claim. In late August, president Killilea said that his club was set to earn from $10,000 to $15,000 for the season.39 And on October 5, 1901, Sporting News correspondent B.F. Wright figured that, after the 10 percent American League fund deduction and disbursements to visiting teams, the Brewers took in about $25,850 at Milwaukee Park, and $25,075 on the road (having a road attendance of over 222,000). With revenue totaling $50,925 – a little more than Cleveland, and not much less than Washington and Baltimore – Wright could not understand how Milwaukee lost money, speculating that the loss claims were intended “to reconcile the Milwaukee fans to the transfer of the club to St. Louis.”40 A contrary perspective, however, was offered by Sporting News correspondent Frank Patterson, who maintained that some franchise attendance reports “were at times very much exaggerated,” with Milwaukee’s “padded very considerable.” Patterson also said Wright underestimated salaries in the American League.41

Whatever the truth, franchise relocation rumors resurfaced. Back on February 25, 1901, the Milwaukee Sentinel had stated that if the Brewers did not transfer before the 1901 season, they probably would before 1902.42 According to a later Sporting News report, the American League picked Milwaukee over St. Louis for the 1901 season “for sentimental reasons.” Or because Killilea had “declined to accede to the request of President Johnson, Charlie Comiskey and others prominent in the American League” to transfer his team to St. Louis “with protestations of civic pride.”43 The talk had died until June, when AL magnates meeting in Chicago said that the league would enter St. Louis and/or New York in 1902, dropping Milwaukee and/or Cleveland.44 In late July, Killilea conferred with Comiskey and Johnson regarding a proposal to transfer the Washington franchise to New York and Cleveland to St. Louis. At that time, Killilea said he would “personally vouch for the retention of this city [Milwaukee] in the circuit.” He also declared that he had just turned down a $30,000 offer for his franchise from St. Louis people, saying the franchise was not for sale at any price. He was certain that in years to come he could turn the Milwaukee club into a “money maker,” and was committed to making every effort to put a strong team on the field.45 But others, including Washington Senators owner Jim Manning, insisted Milwaukee would go to St. Louis. 46

In August a story broke that Ban Johnson had received an option on the stock of the St. Louis National League club, and had given Killilea a chance to take up that option.47 Privately, Johnson was committed to the transfer of the Milwaukee AL franchise to St. Louis, stating, “[T]the players at present with the Milwaukee club are popular in St. Louis and they, with a materially strengthened team, would undoubtedly be well supported there.”48 The Sentinel also believed the Brewers would go to St. Louis. Whatever the particulars, something was definitely brewing in St. Louis. Johnson said the American League would enter St. Louis, but declined to identify which AL city would be dropped.49 For its part, the Milwaukee Daily News was sure it would not be Milwaukee because of Matt Killilea, who “has been one of the staunchest supporters of the American League, and he did as much if not more than any one person to place Ban Johnson in the comfortable berth he has today. Mr. Killilea is high in the councils of the American League and if he cares to have one of its teams here next season his wishes will be respected.”50

In late August, Killilea again turned down an offer for his club. “An authentic source” said some National League ballplayers had formed a syndicate to purchase the Milwaukee franchise. The syndicators, unnamed but believed to be Bid McPhee, Jake Beckley, and Frank Bancroft, “are in the possession of wealth accumulated during a long term of service” and had offered Killilea $42,000 for the Brewers. Reportedly, the syndicate wanted to install the club in St. Louis, but later refocused on the Cleveland franchise when their bid for Milwaukee was turned down.51

By mid-September, reliable sources were again claiming that the Brewers would be transferred to St. Louis, where the roster would be composed of the best Milwaukee players and some St. Louis National League players. With Matthew Killilea ill (no doubt from the effects of the tuberculosis that would take his life), his brother Henry became head of the Brewers. Henry denied such reports, but a St. Louis dispatch alleged that Killilea had secured nine players from the National League Cardinals to play with a St. Louis club in the American League in 1902.52 Meanwhile, Matt Killilea told Milwaukee newspapers that he wanted to retire from baseball and would not run the St. Louis club if the Brewers moved there.53 In late September Philadelphia sources reported another transfer scenario. This one had Ban Johnson making a deal: Killilea’s 40 percent stake in the Milwaukee club would be sold to a St. Louis brewer for $40,000; the franchise would relocated to St. Louis, and Matt Killilea would be president of the club.54 In early October, Henry Killilea went to St. Louis to negotiate the disposal of the franchise, with liberal inducements being offered those opposed to the move. Upon Killilea’s return to Milwaukee, St. Louis dispatches reported that the Brewers would transfer to St. Louis and that Jim McAleer would manage the club. But denials greeted these reports.55 McAleer then went to Milwaukee to talk to Henry Killilea and Fred Gross.56 The Milwaukee Sentinel wrote: “You pays your money and takes your choice” on who was telling the truth.57 The Evening Wisconsin was sure the Brewers would transfer, reasoning,

It is an impossibility for Milwaukee to spend as much money in getting a team together and putting up the salaries requisite to get gilt-edged players and put a team in the field like Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston, and unless the Milwaukee fans are content to travel along as the tail-enders of the American League for another season, the best thing that can be done in the interests of the sport locally will be to quit and get into a class where Milwaukee will be able to hold its own in place of simply serving as the means to fatten the averages and standings of the other teams.58

However, there remained people who thought that Milwaukee could survive in the American League. The Milwaukee correspondent for Sporting Life, for example, wrote on September 28, 1901:

The statement that Milwaukee cannot afford to support a team of equal caliber with Washington and Detroit is absurd. If the Milwaukee magnates engage high-salaried players, and the team makes a favorable showing – that is, winning half of their games – the patronage they will receive will surprise those who are now deriding the ability of Milwaukee for supporting first-class exhibitions of baseball. … Milwaukee will not support a tail-end team or a mediocre aggregation of ball players. It demands the best, and when that is provided there is no limit to the extent of the patronage. … Milwaukee is a better ball town than Baltimore, Cleveland or Washington, and as good as Detroit, and if these cities can afford to secure leading talent for their respective teams for 1901, then the management of the Milwaukee Club can surely take a similar risk.59

Still, evidence of a franchise move kept mounting. On October 10 it was reported Hugh Duffy had resigned as manager of the Brewers, wanting to go back to Boston, but the team denied this story. The following day, Ban Johnson announced that he had signed five players from the Cardinals to play for the new AL St. Louis club. Killilea, however, still denied that any move was in the works.60 These continuing reports and denials led The Sporting News’ correspondent in Milwaukee to write that these were only “one of the thousand little and big things which prove how much confidence may be placed in the announcements of the base ball magnates these days. They have adopted a policy of denying and claiming everything, so that when a piece of news that is authentic is dug up, it must be supported by oaths and pledges, or it looks like the stuff that is being piped by the guess artists of the major league cities.”61 Back in St. Louis, dispatches reported that local bigwigs Gussie Busch, Zach Tinker, and George Heckel would back the club and that they wanted Matt Killilea for president.62 Reports went so far as to name the new St. Louis players, including eight Brewers.63 Others in the American League supported the transfer. Jim Manning and John McGraw, for example, believed that St. Louis would pay visiting clubs $5,000 more during the season than the clubs could get in Milwaukee.64 The Milwaukee Sentinel attacked Johnson and his cronies.

American League magnates are exhibiting a selfish streak of well developed proportions this fall in making an attempt to deprive Milwaukee of its franchise. For years this city was the backbone of the league, supplying Johnson and his associates with the sinews of war even when the team representing Milwaukee was not considered a factor in the championship race. Now that the American League has expanded into a simon pure organization, and simply because the Brewers graced the tail end of the processions … and did not attract the people to the ball grounds as they had in preceding seasons, the other magnates now say ‘T’ell with Milwaukee.’”65

The Milwaukee owners did not give in easily. They set a price tag of $60,000 for the franchise, believing it too high for acceptance.66 They were right. Ban Johnson said, “There is not a club in the country that is worth $60,000 today in these troublesome times of baseball.”67 Back in St. Louis, Zach Tinker backed out, disaffected by the price tag for the Killilea stock and his inability to acquire sole control of the franchise. The Milwaukee press now believed the deal was off and that the Brewers would stay.68 Ban Johnson decreed otherwise, calling Milwaukee a “one day town” that drew good crowds only on Sunday.69 He stated that the Milwaukee franchise would go to St. Louis; that there would be no local money in the club; that the American League would furnish the necessary capital, and that the new St. Louis franchise would be in the league’s “common possession until such time as a proper man could be found to relieve it of the holds and take personal charge.”70

The Johnson declarations notwithstanding, the mess was not clearing up. Pitcher Bill Reidy and three other Milwaukee players said they would seek a salary increase if the club was transferred, as their contracts with the Brewers did not require them to play in St. Louis.71 Pitcher Ned Garvin, who had been 8-20 in 1901, was dissatisfied with the situation and threatened to jump to the National League, as did infielder Billy Gilbert.72 Shortstop Wid Conroy did more than talk, signing with Pittsburgh of the NL.73 All the while, the AL could not find playing grounds in St. Louis at an agreeable price, until old Sportsman’s Park was eventually secured.74

When American League magnates met in Chicago on December 2, 1901, they re-elected Ban Johnson as league president. Fred Gross was present at the meeting, but with Matthew Killilea delayed by the trains, no immediate action was taken on the Milwaukee franchise issue.75 Upon arrival, Killilea told newsmen, “The owners of the Milwaukee club are opposed to the transfer to St. Louis and the American League cannot make a change without the consent of the owners.”76 Word was around, however, that he wanted $48,000 for the franchise.77 Late the following evening, the long-awaited transfer was completed. Matthew Killilea purchased the majority interest of his brother Henry, who did not want Matt in baseball because of his failing health, and transferred the Milwaukee club to St. Louis.78 At the time, St. Louis was the fourth largest city in the country, its 1900 population of 575,238 more than twice that of Milwaukee’s 285,315. Matt Killilea was recognized as president and principal owner of the new St. Louis club. Jim McAleer was named manager.79 William Wallace Rowland of the Milwaukee Journal, writing under the nom de plume of Brownie, did not approve, saying, “It is a very clever trick of the American League bunch in keeping Killilea … on their staff with ground awaiting them in Milwaukee in case St. Louis should go to the bad.”80 The Milwaukee Daily News, bitter over the transfer, wrote that Killilea and Gross “have pink tea in their veins instead of sporting blood” for not taking a chance on Milwaukee.81 The Milwaukee Sentinel, however, said of the transfer:

The owners of the Milwaukee club removed their team to St. Louis as a business proposition. They expected to sell out, but the absence of capitalists in the Mound City to shoulder the burden made it necessary for them to carry the load themselves, and it is possible that they may make their independent fortunes as a result of the move. The Killileas and F.C. Gross stated that Milwaukee could not adequately support the expensive team they had secured; so they had to leave the city.82

Because of poor health, Matthew Killilea spent the winter in Texas and left George Munson, one-time secretary to Chris von der Ahe of the old St Louis Browns, to run the franchise in his absence.83 Some, the Milwaukee Daily News and the Chicago American included, doubted if Killilea was really running the club given his health, speculating that Johnson and Comiskey were looking after the finances of the club.84 In January 1902, Matthew Killilea sold out to a St. Louis syndicate for a reported $40,000. Then, he and brother Henry bought into the American League Boston club.85 Six months later, Matt Killilea was dead from tuberculosis, at the age of 40.86

In some ways, the Brewers’ transfer from Milwaukee to St. Louis was a matter of timing. In September 1901 Matthew Killilea reportedly said, “If there was no war, then Milwaukee would be sure to remain in the American League. You must fight the devil with fire, and the American League must go into the National League’s territory to wage a successful war. Before peace is declared the American League will doubtless be in New York and St. Louis.”87 Time would prove Killilea correct.

DENNIS PAJOT was born in Milwaukee, raised and schooled in Milwaukee, worked for and retired from the City of Milwaukee, still lives in Milwaukee. Happily or sadly, that says it all about Dennis.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this chapter were taken by permission from Dennis Pajot, The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball: The Cream City from Midwestern Outpost to the Major Leagues, 1859-1901 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company 2009).

Notes

1 Andrew J. Aikens and Lewis A. Proctor, eds., Men of Progress, Wisconsin (Evening Wisconsin Co., 1897), 115

2 1895 Spalding Baseball Guide, 131; Milwaukee Sentinel, September 26, 1894.

3 Milwaukee Journal, October 21,1894; Milwaukee Sentinel, October 21, 1894, and February 27, 1895.

4 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 23, 1895.

5 Milwaukee Journal, February 20, 1893.

6 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 11, 1896.

7 Milwaukee Sentinel, January 11 and September 13, 1896.

8 Milwaukee Journal, September 22, 1896.

9 1898 Spalding Base Ball Guide, 115; Milwaukee Journal, September 2, 1897.

10 The Sporting News, October 23, 1897.

11 1899 Spalding Baseball Guide, 10; Milwaukee Sentinel, October 15, 1898.

12 The Sporting News, September 30, 1899.

13 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 19, 1899.

14 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 21, 1899; Sporting Life, December 30, 1899.

15 Sporting Life, October 21, 1899 .

16 Sporting Life, March 3, 1900.

17 Milwaukee Journal, February 27, 1900.

18 Sporting Life, May 17, 1900; Milwaukee Daily News, April 12, 1900.

19 1901 Reach Baseball Guide, 7.

20 Evening Wisconsin, September 19, 1900.

21 Milwaukee Journal, November 5, 1900.

22 Milwaukee Sentinel, November 23, 1900.

23 The Sporting News, December 22, 1900, and February 16, 1901; Milwaukee Sentinel, December 25, 1900.

24 Milwaukee Sentinel, January 29, 1901.

25 Milwaukee Journal, February 20, 1901; Milwaukee Sentinel , February 25, 1901.

26 Milwaukee Sentinel , February 25, 1901.

27 Milwaukee Sentinel, February 3, 1901.

28 Milwaukee Journal, March 30, 1901.

29 Milwaukee Sentinel, March 31, 1901.

30 Milwaukee Journal, April 11, 1901.

31 Milwaukee Sentinel, March 21, 1901

32 Milwaukee Sentinel, April 26, 1901

33 Baseball-Reference.com.

34 Milwaukee Daily News, September 30, 1901.

35 Baseball-Reference.com.

36 The Sporting News, September 28, 1901.

37 The Sporting News, October 19, 1901

38 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 30, 1901.

39 Milwaukee Sentinel, August 29 1901

40 The Sporting News, October 5, 1901.

41 The Sporting News, October 12, 1901

42 Milwaukee Sentinel, February 25, 1901.

43 The Sporting News, September 21, 1901.

44 Milwaukee Sentinel, June 5, 1901.

45 Milwaukee Sentinel, July 30 and August 1, 1901.

46 Milwaukee Sentinel, August 14, 1901.

47 Milwaukee Sentinel, August 9, 1901.

48 The Sporting News, August 24, 1901.

49 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 6, 1901.

50 Milwaukee Daily News, June 22, 1901.

51 Milwaukee Sentinel, August 30, 1901; Milwaukee Daily News, August 30, 1901.

52 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 15, 1901.

53 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 16, 1901.

54 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 27, 1901.

55 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 6 and October 10, 1901.

56 Milwaukee Journal, October 9, 1901.

57 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 11, 1901.

58 Evening Wisconsin, September 16, 1901.

59 Sporting Life, September 28, 1901.

60 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 11 and October 12, 1901.

61 The Sporting News, October 19, 1901.

62 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 17, 1901.

63 Milwaukee Journal, October 19, 1901.

64 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 24, 1901.

65 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 13, 1901

66 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 20, 1901.

67 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 22, 1901.

68 Milwaukee Sentinel ,October 29, 1901

69 Milwaukee Sentinel, November 8, 1901.

70 The Sporting News, December 7, 1901.

71 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 31, 1901.

72 Milwaukee Sentinel , November 20, 1901; Evening Wisconsin, October 12, 1901.

73 Milwaukee Journal, November 21, 1901.

74 Milwaukee Journal, November 22 and December 7, 1901.

75 Milwaukee Sentinel, December 3, 1901; Milwaukee Journal, December 3, 1901.

76 Milwaukee Journal, December 3, 1901

77 Ibid.

78 Milwaukee Journal, December 4, 1901; Milwaukee Sentinel, December 4, 1901.

79 Milwaukee Sentinel, December 4, 1901.

80 Milwaukee Journal, December 4, 1901.

81 Milwaukee Daily News, December 6, 1901.

82 Milwaukee Sentinel, December 6, 1901.

83 Milwaukee Journal, December 7, 1901.

84 Milwaukee Daily News, December 7, 1901.

85 Milwaukee Sentinel, January 28 and January 29, 1901.

86 Milwaukee Sentinel, July 28, 1902.

87 Sporting Life, September 28, 1901.