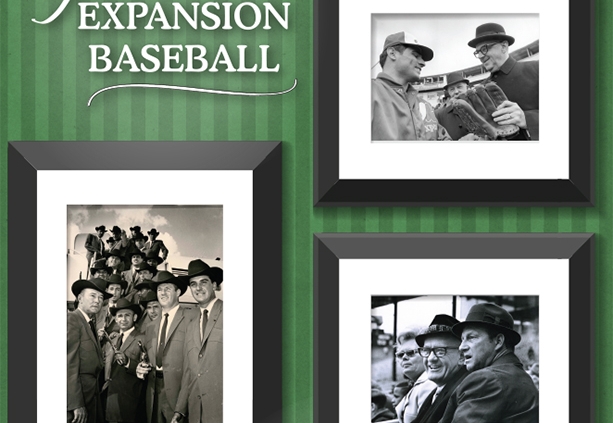

“The Name Is Mets – Just Plain Mets”

This article was written by Leslie Heaphy

This article was published in Time For Expansion Baseball (2018)

As part of the National League expansion in 1962, a franchise was awarded to New York City. From 1962 to the current day the Metropolitans’ ownership has been fairly stable. Joan Payson and her family maintained control of the club until they sold the team in 1980 to the publishing firm Doubleday and Co. Nelson Doubleday bought out the company in 1986 with his partner Fred Wilpon. In 2002 Wilpon and Sterling Equities bought out Doubleday and as of 2018 have remained the primary owners. This relative stability in ownership for the Mets has not prevented them from experiencing incredible highs and lows during the franchise’s history. Two World Series, in 1969 and 1986, brought the Mets to the highest honor in baseball while they began their existence with the worst record in major-league history in 1962.

As part of the National League expansion in 1962, a franchise was awarded to New York City. From 1962 to the current day the Metropolitans’ ownership has been fairly stable. Joan Payson and her family maintained control of the club until they sold the team in 1980 to the publishing firm Doubleday and Co. Nelson Doubleday bought out the company in 1986 with his partner Fred Wilpon. In 2002 Wilpon and Sterling Equities bought out Doubleday and as of 2018 have remained the primary owners. This relative stability in ownership for the Mets has not prevented them from experiencing incredible highs and lows during the franchise’s history. Two World Series, in 1969 and 1986, brought the Mets to the highest honor in baseball while they began their existence with the worst record in major-league history in 1962.

Birth of the Metropolitans

In 1957, when the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left New York for the West Coast, Gotham City fans were left reeling and looking for a replacement. The 1958 season would be the first since 1882 for New York not to host a National League team. A number of groups stepped forward and talks developed about who might emerge to take over this market.

Late in 1957, New York Mayor Robert Wagner Jr. appointed a committee to bring National League baseball back to the city. While luminaries such as former Attorney General James Farley, department-store mogul Bernard Gimbel and real-estate impresario Clinton Blume sat on the panel, the real power was attorney William Shea. Shea hoped to lure one of the league’s weaker members to New York. However, as talks with the Cincinnati Reds, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Philadelphia Phillies all failed, he decided to propose the creation of a third league, to be called the Continental League. Shea even coaxed Branch Rickey out of retirement to spearhead efforts to establish the league.

With Rickey at the helm, the league would initially field eight teams, including a New York entry, with plans to expand to 10. After nearly half a century as a major-league player, manager, and executive, Rickey knew that any challenger league would require strong ownership to provide the money to develop a front office, sign players, and, perhaps, build a stadium. In New York, the Continental League found its potential owners in the city’s old money.

The group was led by Joan Whitney Payson and her husband, Charles Shipman Payson. Her minority partners included George Herbert Walker Jr., an executive with merchant banker Brown Brothers Harriman (and uncle of President George Herbert Walker Bush), and Dwight F. Davis Jr., son of the founder of tennis’s Davis Cup. Another was Payson’s stockbroker, M. Donald Grant.1 As a member of Horace Stoneham’s board, Grant had been the only director to vote against the Giants moving out west. He voted “no” on behalf of Payson, who would rather have had the Giants than the extra money.2

After two years of resisting the Continental League, the National and American Leagues finally rallied around to the idea of expansion in late 1960. They also faced pressure from the US Congress, who threatened baseball’s exemption from antitrust laws if they did not agree to expansion. According to the announcement from National League President Warren Giles, two teams would be added to the National League through ownership groups from the Continental League groups. National League play was to begin in New York and Houston in 1962.3

The decision gave Payson the distinction of being the first female major-league-baseball franchise owner in four decades and the first who did not own the franchise without inheriting it. She first became involved in baseball by buying one share of stock in the New York Giants in 1950 and gradually increased her involvement to a 10 percent share by the mid-1950s. Before the Giants moved to San Francisco, she gave some thought to investing more heavily to keep the franchise in New York. However, she sold her shares when the Giants followed the Dodgers to the West Coast. Payson’s interest in baseball came from her mother but it was not her only sporting interest. She also invested heavily in horse racing, owning a stable with her brother, Jock Whitney.4

Joan Whitney was born in New York in February 1903 to a family with an impressive lineage dating back to their arrival in Massachusetts from England in 1635. Her father, William Payne Whitney, came from a family line that included Henry B. Payne, a Democratic senator from Ohio in the 1850s. Payne Whitney had not only inherited money but added to his fortune with investments in banking, tobacco, railroads, mining, oil, and Greentree Stables.

His own father, William C. Whitney, served as secretary of the Navy during the first Grover Cleveland administration and owned a streetcar line in Boston. Payne Whitney’s uncle, Col. Oliver Payne, left his fortune to his nephew when he died in 1917. Joan’s mother, Helen Hay Whitney, of Cleveland, was the daughter of John Hay, who began his career as assistant private secretary to President Abraham Lincoln. Hay went on to serve as secretary of state under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Joan and her brother inherited her father’s fortune upon their father’s death in 1927.

Joan Whitney married Charles Shipman Payson when she was 21. Their marriage at Christ Church in Manhattan was a huge social event uniting two old-time wealthy families in 1924. During the course of their marriage they had five children, three girls and two boys. Joan continued to oversee and invest her own money in horses, art, and, ultimately, the New York Mets.5

After paying $1 million for her primary investment, Mrs. Payson moved quickly to organize and name her new ballclub. In March 1961, the first major management decision was made: to hire George Weiss as president and general manager. Weiss’s tenure with the New York Yankees from 1932 to1960 had been incredibly successful, as attested by his ultimate election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971. Weiss insisted on bringing on board Casey Stengel as the new manager.6 Then in May 1961, Payson hosted a gathering at her Manhattan home to name the new team. According to some of those present, Payson’s personal favorite was the Meadowlarks but the New York Metropolitans was chosen. The Metropolitans had been the name of the American Association club in New York from 1882 to 1887. Payson herself announced the name at the Savoy on May 8, 1961, indicating that the team would be known by the nickname Mets. A new logo was commissioned from sports cartoonist Ray Gotto and unveiled in November 1961. The colors incorporated Dodgers blue and Giants orange to encourage support from fans of these former franchises.

M. Donald Grant first met Joan Payson at a club in Florida in 1950. Over a game of cards the conversation had shifted to what each of them would buy with their money. Payson and Grant both wanted to buy the New York Giants. From there a lifelong friendship and working relationship began. Grant was born in Montreal in 1904, the son of Michael Grant, a professional hockey player. He eventually found his way to New York to make his fortune. He started as a night clerk and worked his way up to being a managing partner in Fahnestock and Company while also serving on the board of the Mets.7 Grant went to work for Payson after selling his one percent share of the Giants to her. Eventually she came to own 10 percent of the club and Grant represented her on the board of directors. While Grant was a minority owner of the Mets, Mrs. Payson claimed that her investment was about 85 percent of the team.8 Grant served as the chairman of the board until he resigned in 1978.

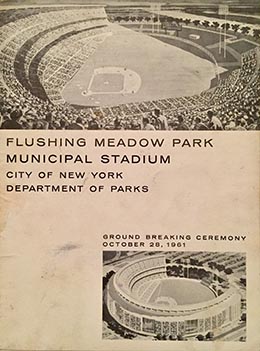

Program from the groundbreaking ceremony at Flushing Meadow Park on October 28, 1961. Shea Stadium opened in 1964, just in time for the New York World’s Fair. (Courtesy of James Cornell)

One of the biggest concerns for Payson and the other major-league owners was where the Mets would play. Plans were immediately underway to construct what was to be known as Flushing Meadows Stadium, a 55,000-seat ballpark with a price tag of $15 million. However, it would never be ready for the first season. One proposal was to share Yankee Stadium for a year or two, but Yankees ownership was not interested in anything less than a long-term rental agreement. The Mets then turned to the Polo Grounds, the former home of the Giants, which was scheduled to be razed. Mayor Wagner worked to delay the destruction, allowing the Mets to play their inaugural home opener on April 11, 1962, a game they lost 11-4 to the St. Louis Cardinals. The Mets went on to have the worst record (40-120) of any major-league team since 1935 and an attendance of only 922,530 for the season. They ended the season in 10th place, 60½ games out of first place.9

When Shea Stadium finally opened for the Mets to play their home opener on April 17, 1964, it was supposed to be the state of the art in ballparks. Usher Stan Manel, an employee of the Mets since 1962, commented that moving from the Polo Grounds to Shea “was like moving from the basement to the penthouse.”10 Sadly, the reality was different, though the outcome of that first game was as expected. The Mets lost to the Pittsburgh Pirates, 4-3. When Shea Stadium was first proposed, the venue was planned to be part of urban planner Robert Moses’ vision for all of Flushing Meadows. Moses originally used the idea to try to entice Walter O’Malley to move the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Queens.

Shea and Moses had to find a way around an existing New York state law that prohibited the city from borrowing money to build a stadium. The only way around the law was to prove that the stadium could pay for itself from rent and event revenue. If the new team paid a substantial annual rent, then 30-year bonds could be paid off and no borrowings were required. All Shea and Moses had to do was convince others that the idea could become a reality. With the endorsement of the New York Times and local dignitaries Stengel and Weiss and civic leader Bernard Gimbel, the deal was reached and construction began. The Mets were never able to live up to that monetary commitment, which would cause difficulties when Fred Wilpon wanted a new ballpark three decades later. The Mets were also granted exclusive rights to Shea during the course of the baseball season by Parks Commissioner Newbold Morris. One of the other features of Shea Stadium was the fact that the park was built for multiple tenants, a trend for municipal stadium development in the 1960s. Due to his efforts in bringing National League baseball back to New York, William Shea became the logical person to name the new ballpark after.11

The ballpark was dedicated the day before the home opener in 1964 with Shea, Wagner, Moses, Stengel, Payson, and many dignitaries in attendance. Shea christened the new field with water from the Harlem River and the Gowanus Canal. The Polo Grounds had stood on the banks of the Harlem, and its water represented the lost Giants, while the canal ran through Brooklyn near an early field of the Dodgers.

Manel, the usher, described the home opener in the following way:

Over 50,000 fans showed up on opening day. There was a great traffic jam outside the ball park. some fans did not get to their seat until the sixth inning. The paint was still wet in some places. The score board was not yet completed. The color of your ticket matched the color of the level on which the seat was located. The crowds were great. Over 1.7 million fans came out that season. The 1964 Worlds Fair was located across the road.12

Shea Stadium was plagued by financial issues and water concerns throughout its life. Since Shea was built on marshland, it had constant drainage issues. Those issues were compounded when the outfield fences were moved in and the drainage pipes were then outside the fences. The planned 80,000-seat expansion and dome did not happen because of financial shortfalls. The financial woes would continue to plague the Mets for their entire tenancy, and later affected how the city dealt with the desire by both the Mets and Yankees for new ballparks.13

Part of the blame for the terrible start can be placed squarely on the shoulders of the aging and increasingly disengaged Casey Stengel. But the 1961 expansion draft was the primary trouble. Each National League team had to make 15 players available for the Houston and New York teams to draft. The draft was scheduled for the period before major-league teams had to add blue-chip prospects to their 40-man rosters and thus be eligible for selection. The Mets selections came primarily from players at the end of their careers or players without any big-league experience yet. Coupled with the declining skills of Casey Stengel, who was the oldest manager in the major leagues at the time, the Mets got off to a dismal start.

The draft was scheduled for October 10, 1961, and would be conducted in three phases. Each team could select four premium players ($125,000 each), 16 players at $75,000 each, and three at $50,000 each. Houston won the coin toss and received the first pick. The selections alternated through the allowed 45 picks. Together the teams spent $3,650,000 for the drafted players. The Mets used their first pick to select Hobie Landrith from the Giants. Landrith was included in a trade with Baltimore on June 7, 1962, that brought Marvelous Marv Throneberry to New York. When the draft was complete, the Mets had selected 22 players for under $1.8 million, which left room for acquiring players such as Frank Thomas from the Braves. The best player they selected was clearly Gil Hodges, an eight-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove winner nearing the end of his playing days. After retiring, Hodges managed the Mets to their first World Series win, in 1969.14

Payson and her fellow board members did not lose heart, bolstered by the unexpected attendance success in spite of the team’s on-field performance. The team drew over a million fans in its second year, despite another dismal performance, and then shot to 1.7 million, second in the league, the year Shea Stadium opened. Stan Manel said, “If you came to our ball park, we gave you nine full innings of baseball. Not the eight and a half you get with a winning team. We did however draw over 900,000 fans, with 55,000, at a double header on Memorial Day with the Dodgers. We drew over a million the second year.”15 The success continued for much of the next two decades.

Owner Payson did not get involved in many of the day-to-day decisions of the ballclub. She preferred to remain in the background and be the team’s number-one fan. She attended games regularly, took care of the players and even decorated part of her house in Mets colors. One of the few personnel decisions she weighed in on was bringing Willie Mays to the Mets in 1972, as he had been her favorite player with the Giants. Much of the operational work was done by the general managers, front-office staff, and M. Donald Grant; though Grant indicated in an interview that he was credited with more input in decisions than he ever gave. He claimed he never interfered in the choices made by the general managers but just offered advice and counsel.16

With the expansion of the National League, New York once again had its entry in the league and the fans had the new “lovable losers” to root for. Joan Payson took her love of the game to the next level when she purchased the franchise and was lucky enough to be the owner while the Mets rose from the doldrums to the highest honor, winning the World Series in 1969.

LESLIE HEAPHY, associate professor of history at Kent State University at Stark, is a lifelong Mets fan and author/editor of books on the Negro Leagues, women’s baseball, and the New York Mets.

Notes

1 Dick Young, “The Mets Are Born: NL Votes to Return to NY in 1962,” New York Daily News, October 18, 1960; Peter Bendix, “The History of the American and National League, Part I,” beyondtheboxscore.com/2008, November 18, 2008; Mike Barry, “Payson’s Legacy,” antonnews.com, May 18, 2012.

2 George Vecsey, Joy in Mudville (New York: McCall Publishing Company, 1970), 13.

3 Vecsey, 15-16.

4 Joseph Durso, “Joan Whitney Payson, 72, Mets Owner, Dies,” New York Times, October 5, 1975.

5 “Payne Whitney Dies Suddenly at Home,” New York Times, May 26, 1927.

6 Burton A. Boxerman and Benita W. Boxerman, George Weiss: Architect of the Golden Age Yankees, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016), 164.

7 Murray Chass, “Mets Chairman M. Donald Grant, 94, Dies,” New York Times, November 29, 1998. In Donald Grant file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Library, Cooperstown, New York.

8 Durso.

9 Mike Dodd, “MLB Expansion Effects Still Felt 50 Years Later Around the Leagues,” USA Today, April 11, 2011.

10 Email Correspondence with Stan Manel, May 2018.

11 Chris Strohmaier, “Shea Stadium, Robert Moses, and an Era of Ballparks,” amazinavenue.com/2014/10/13/689131/mets-shea-stadium October 3, 2014; Jack Lang, “Yanks in Shea Stadium? Idea Enrages Mets,” Long Island Press, September 18, 1971, in Donald Grant file; “History of Shea Stadium,” New York Mets, accessed June 5, 2018, newyork.mets.mlb.com/nym/ballpark/history.jsp.

12 Email correspondence with Stan Manel.

13 Eric Barrow, “Shea Stadium: Mets First Miracle,” New York Daily News, October 23, 2008.

14 “1961 MLB Expansion Draft,” Baseball-reference.com; Vecsey, 31-33.

15 Email correspondence between author and Stan Manel, May 2018.

16 Dick Young, “Don Grant: I Took Blame for Things I didn’t Do,” New York Daily News, November 25, 1978, in Donald Grant file.

|

NEW YORK METS EXPANSION DRAFT |

|||

|

PICK |

PLAYER |

POSITION |

FORMER TEAM |

|

REGULAR PHASE, $75,000 PER PLAYER |

|||

|

1 |

Hobie Landrith |

c |

San Francisco Giants |

|

2 |

Elio Chacon |

ss |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

3 |

Roger Craig |

p |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

4 |

Gus Bell |

of |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

5 |

Joe Christopher |

of |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

6 |

Felix Mantilla |

2b |

Milwaukee Braves |

|

7 |

Gil Hodges |

1b |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

8 |

Craig Anderson |

p |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

9 |

Ray Daviault |

p |

San Francisco Giants |

|

10 |

John DeMerit |

of |

Milwaukee Braves |

|

11 |

Al Jackson |

p |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

12 |

Sammy Drake |

ss |

Chicago Cubs |

|

13 |

Chris Cannizzaro |

c |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

14 |

Choo Choo Coleman |

c |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

15 |

Ed Bouchee |

1b |

Chicago Cubs |

|

16 |

Bobby Gene Smith |

of |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

REGULAR PHASE, $50,000 PER PLAYER |

|||

|

17 |

Ed Olivares |

2b |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

18 |

Jim Umbricht |

p |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

PREMIUM PHASE, $125,000 PER PLAYER |

|||

|

19 |

Jay Hook |

p |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

20 |

Bob Miller |

p |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

21 |

Don Zimmer |

3b |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

22 |

Lee Walls |

of |

Philadelphia Phillies |