The Planting of Le Grand Orange

This article was written by Norm King

This article was published in Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal

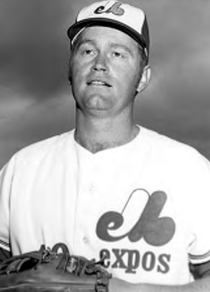

No one knew it at the time, but the January 22, 1969, trade that sent Rusty Staub from the Houston Astros to the Montreal Expos was arguably the most significant player transaction in baseball since Harry Frazee sold Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees in 1920. The actions of the players involved showed that baseball management was beginning to lose its hold on the absolute power it enjoyed over players for nearly a century. The trade brought a new franchise its first iconic player and gave a new, fill-in Commissioner a chance to flex his muscle and become a fixture as head of Major League Baseball. The trade also eventually led to a miracle.

The Astros sent Staub to Montreal in return for first baseman Donn Clendenon and outfielder Jesus Alou, but the mechanics of the deal go back to October 14, 1968, when Montreal drafted Clendenon and Alou in the expansion draft. Clendenon’s 1968 numbers with Pittsburgh were solid: He had a .257 batting average with 17 home runs and 87 RBIs. But he was turning 33 and was on the downside of his career. The method to the Expos’ madness in drafting Clendenon and Alou was to choose players who could serve as potential trade material. “We went for players, who number one had a name, who could still play, and who had trading value, or value period to someone else,” explained former Expos general manager Jim Fanning.1

Houston expressed interest in Alou as early as the 1968 winter meetings, offering pitcher Mike Cuellar in exchange for the former Giants outfielder. Montreal turned that down. The Expos also initially nixed the Staub for Clendenon and Alou deal because Expos management thought they’d be giving up too much to get Staub. (Montreal also had a chance to swap Clendenon for pitchers Jim McAndrew and Nolan Ryan, but Mets manager Gil Hodges vetoed the trade). Some back-and-forth talks took place over the next several weeks until the transaction was concluded.

On the surface, it seemed like an odd deal from Houston’s standpoint. The Astros (then known as the Colt .45s) signed Staub as a much-ballyhooed bonus baby out of Louisiana in 1961 at age 17, and brought him up to the big club after one year in the minors. He struggled his first two years before finding his stride and stroke in 1967 when he batted .333—fifth in the National League—with 10 home runs, 74 RBIs, and a league-leading 44 doubles. In 1968, Staub hit .291 (good enough for ninth place in the batting race), with six home runs and 72 RBIs—good numbers in “The Year of the Pitcher.” Also, he would be only 25 years old on April 1, approaching the prime of his career. In return, the Astros were getting players that had been left off their original team’s protected list.

The fact was that Houston wanted to get rid of Staub. He had held out for the first eight days of spring training in 1968 before signing for a reported $45,000. That didn’t endear him to Astros general manager “Spec” Richardson; all general managers in that era deemed any player demanding a larger salary or thinking independently to have an attitude problem. Staub’s decision to sit out the game against the Pirates on June 9, 1968—in commemoration of the assassination of Robert Kennedy—didn’t win him any brownie points with Astros brass, either. President Lyndon Johnson had designated that date as a day of national mourning. The Astros chose to go on with the game as scheduled, but Staub and teammate Bob Aspromonte chose not to play. The two players were each fined a day’s pay, which in Staub’s case amounted to $300.

“There was mutual disenchantment between Staub and the Astros management, which had been compared—with reason—to a Boy Scout operation,” wrote Mark Mulvoy in Sports Illustrated. “At spring training the players are locked into barracks every night. Almost every night during the season there’s a bed check. ‘The entire operation is gripped by fear,’ Staub says. ‘Everything is an ultimatum.’”2

Staub was having contract issues with Houston again at the time of the trade, and was blunt in telling the media he was glad to leave the Astros. “I like this town, yes, but the organization—no,” he said. “The contract they sent me was almost laughable. It was an insult to my intelligence. They did not ask me to take a minute cut, they asked me to take a nice cut.”3

The Expos, for their part, were thrilled to get Staub. Expos manager Gene Mauch was delighted to have him. “I always knew Rusty had beaucoup power even before I knew what beaucoup meant,” Mauch said.4

The Houston-area media were confounded by the deal. “With .300 hitters in short supply everywhere, a team with no one else remotely in that class certainly wouldn’t deal one away,” wrote columnist Emil Tagliabue in a piece aptly titled “Staub Mystery.” “But Richardson would, and has, sending the smooth-stroking redhead to the new Montreal franchise in exchange for a couple of journeymen with credentials something less than eyebrow-raising.”5

Journeymen would be an apt description for Alou and Clendenon. Alou was only 26, but he had had a mediocre year with the Giants in 1968, batting .263 with no home runs and only 39 RBIs. He would have trouble improving his productivity playing his home games in the pitcher-friendly Astrodome. (He did hit five home runs in 1969, but four of those were on the road; he also batted only .248 and drove home 34 runs).

The deal was also unusual in that Houston had already acquired Curt Blefary from Baltimore to play first base in a trade which sent Mike Cuellar to Baltimore. (Cuellar went on to share the 1969 Cy Young Award with Denny McLain.) Clendenon was also primarily a first baseman, and while he had power, his numbers were declining. After hitting for a .299 batting average with 28 home runs and 98 RBIs in 1966, his batting average fell to .249 with 13 home runs and 56 RBIs in 1967.

At first it seemed as if the trade would proceed routinely. Clendenon even attended a press conference at the Astrodome Club in Houston in February. While there, he and Richardson talked contract, at which point Richardson told him to expect a pay cut. Clendenon returned to Atlanta without signing.

Richardson didn’t know what he was getting into dealing with Clendenon, who was an anomaly among ballplayers at the time; he was well educated, and had used the offseason to pursue other career interests. In 1961, for example, he worked as a management trainee with the Mellon Bank in Pittsburgh. In 1967, he became the assistant personnel director at the Scripto Pen Company.

Clendenon’s position with Scripto gave him something few players had—leverage. After his discussion with Richardson, Clendenon returned to Atlanta and met with Scripto CEO Arthur Harris who offered to double his salary if he would work for the company full time. On February 28, Clendenon stunned the Astros by abruptly announcing his retirement in order to work at Scripto. He even sent a telegram to the Astros informing them of his decision and asking them to place him on the voluntarily retired list.

While the evidence seems to indicate that Clendenon’s retirement announcement was a tactic to get a higher salary, some people thought his motives went deeper than that. In his autobiography, Jimmy Wynn—who was Staub’s teammate in Houston and a friend of Clendenon’s—wrote that Clendenon did not want to play for Astros manager Harry “The Hat” Walker.6 Walker was from Birmingham, Alabama, and the brother of Fred “Dixie” Walker, who was infamous for requesting a trade from the Brooklyn Dodgers rather than play with Jackie Robinson. Harry’s racial attitudes weren’t any more enlightened, a fact that Clendenon knew from having Walker as his manager with the Pirates.

“Clendenon had played for Walker at Pittsburgh and he wanted no further part of him,” wrote Wynn. “Donn even explained to several of us [Houston players] by phone that he would love to play with us in Houston, but not if it meant again enduring the racist stupidity of another spin with Harry Walker.”7

Clendenon’s tactic of using retirement as a bargaining chip was not unprecedented; it was about the only ammunition players had in the days of the reserve clause. In 1966, Los Angeles Dodgers pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale staged a joint holdout during spring training in an effort to get new contracts of $1 million each over three years. At one point during the standoff, Koufax intimated that the two might retire, telling reporters that “he and Drysdale needed time to ‘reflect on what we want to do with ourselves if we don’t play this season or ever again.’”8 The two eventually ended their holdout, with Koufax signing for $125,000 and Drysdale settling for $110,000 for the 1966 season.

Clendenon’s announcement sent shockwaves through the Astros and Expos organizations. Houston wanted the deal voided, while Montreal wondered whether Pittsburgh owed them a player as compensation for losing Clendenon. There was also the question of whether Clendenon was serious in his intention to retire, and what impact that would have on the Expos’ bargaining position. This was, indeed, a situation that called for the wisdom of Solomon. Instead, National League President Warren Giles and new Commissioner Bowie Kuhn entered the fray.

Kuhn hadn’t even unpacked the boxes in his office when the matter was dropped in his lap. He became Commissioner on February 4, two months after the owners fired his predecessor, William D. Eckert. His first decision in the matter was to ask the teams to keep Staub and Alou out of uniform. What followed, from Houston’s perspective at least, was a farcical succession of events worthy of the Keystone Kops.

Clendenon was suddenly a very popular individual with all kinds of suitors wanting to talk to him. Fanning and Expos President John McHale called him on March 2, a move that Richardson perceived to be tampering. Giles and Kuhn then called Clendenon to tell him—perhaps in an effort to pressure him to comply—that they didn’t accept his retirement claim. Giles and Kuhn then held a meeting on March 6 with Expos and Astros senior management in West Palm Beach to hammer out a solution, or at least to allow Kuhn to make a decision. At the same time, McHale and Richardson visited Clendenon in Atlanta to determine if he was going to stay retired. According to Richardson, he walked away convinced that he was still retired. Kuhn and Giles, though, weren’t accepting Clendenon’s retirement, despite his insistence to the contrary.

It’s not as if the Expos weren’t above a little subterfuge themselves in the effort to keep Staub. One day when Kuhn was about to arrive at Expos spring training camp for a visit, McHale persuaded team owner Charles Bronfman and Staub to put on uniforms. When Kuhn arrived, Fanning got an Associated Press photographer he knew to shoot a photo of the assembled group.

“So this time he [the photographer] comes out and takes this picture of Bowie, John, Charles, Rusty, and me,” said Fanning. “The photographer sent that all over the world. We publicized this picture and it was tantamount to Rusty being a Montreal Expo.”9

Let’s not forget that Alou was also in a predicament because he wasn’t sure where he’d be playing. He went to spring training with Houston and despite his anxieties over the uncertainty of his situation, he acted in a professional manner and worked to get into shape. His behaviour impressed his new teammates.

“[Alou] conducted himself like a big leaguer,” said pitcher Don Wilson. “He never said anything but that he was going to get in shape to play baseball and he was going to play the best he could wherever he played.”10

But trying to go about business as usual was difficult for the players involved. At one point at the end of March Staub said he’d be willing to leave baseball. “I gotta admit it’s starting to wear on me now,” Staub said. “Not only that, but it’s also disturbing my mother and father.”11

On March 8, Kuhn ruled that the deal would stand and that the Expos would have to give Houston another player to replace Clendenon. Kuhn used his authority as Commissioner to override Baseball Rule 12-F, which said that, “a trade is nullified when one player retires within 31 days after the start of a season without having reported to the assigned club.”12

“From the moment the Staub trade was announced, and before it hit the skids by Clendenon’s refusal to report, the Expos had embarked on an immediate marketing plan of selling Rusty Staub to the fans of Montreal as the new face of Expos Baseball,” wrote Wynn. “It was a trade that hit the point of no return from the moment it was announced and Commissioner Kuhn agreed with that kind of thinking.”13

Kuhn’s decision sparked outrage in Houston. Astros president Judge Roy Hofheinz was furious and went so far as to file a petition in a Houston District Court hoping to get a declaratory judgment against the Expos and “at least” $10,000 in damages.

Hofheinz also had some pretty strong words about Kuhn. “This johnny-come-lately [Kuhn] has done more to destroy baseball in the last six weeks than all of its enemies have done in the last 100 years. There is no way we can have 11 clubs protected by the rules and the Houston club unprotected.”14

Kuhn was in a tough spot. Being new in the position, he could either hold firm or give in to Hofheinz, which would signal to the other owners that they could run roughshod over him as well. Kuhn was an interim commissioner at that point and didn’t get a contract for a full seven-year term until 1970. He stood his ground, though, sticking to his decision that Clendenon belonged to the Expos. Finally, on April 3, Clendenon unretired and signed with Montreal after agreeing to a $14,000 raise over his 1968 salary of $35,000. They then offered him to the Astros, but to Houston he was now damaged goods. Instead, Montreal sent Jack Billingham and Skip Guinn, plus $100,000 U.S. Hofheinz dropped his suit after Clendenon signed. (Kuhn also later asked for—and received—an apology from Hofheinz for his remarks.)

The trade was one of the best deals the Expos ever made. Staub had three All-Star seasons for Montreal, and the player and the city had a mutual love affair that lasted until he was traded to the Mets prior to the 1972 season for Ken Singleton, Tim Foli, and Mike Jorgensen. Clendenon didn’t stick around very long; Montreal traded him to the Mets on June 15, 1969, for Kevin Collins, Steve Renko, and three career minor leaguers. At the time of the trade, New York had a 30–26 record, 9 games behind the division-leading Chicago Cubs. They went 70–36 the rest of the way, swooping past the Cubs to win the very first National League East title. After sweeping Atlanta in three games in the NLCS, they upset the Baltimore Orioles in five games, to forever be known as the Miracle Mets. Clendenon hit three home runs in the Series and was named Series MVP.

The Astros? Well, they had their first .500 season in 1969, finishing 81-81, which wasn’t much comfortconsidering that the Mets—who had joined the National League the same year as Houston—went all the way. The Staub and Cuellar deals that Richardson made after the 1968 season not only deprived the Astros of star players, they did not receive adequate compensation in return.

Clendenon’s action caused a domino effect. In April 1969 the Boston Red Sox traded Ken “The Hawk” Harrelson to the Cleveland Indians. Harrelson opted to retire instead of reporting to the Indians, citing his Boston business interests. A new contract calling for a $75,000 salary, plus an additional $25,000 for doing promotional work, changed Harrelson’s mind.

That June, Expos shortstop Maury Wills pulled the retirement trick in reverse, using the retirement gambit to force a trade. He chose to call it a career rather than continue playing in Montreal because he had a dry cleaning business on the West Coast. On June 11, Montreal traded Wills and Manny Mota to the Dodgers for Ron Fairly and Paul Popovich.

The actions of Clendenon, Staub, Harrelson, and Wills all took place as the Major League Baseball Players Association was beginning to assert itself under its executive director, Marvin Miller. The Staub-Clendenon controversy happened amidst the threat of a player strike during spring training; the walkout was averted when the owners agreed to changes to the players’ pension plan. Players could now qualify for the pension after four years of service instead of five, and could begin collecting benefits at age 45 instead of 50.

Oddly enough, the retirement strategy that worked for Clendenon became an impediment for Curt Flood, a center fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals who chose to fight the reserve clause in court rather than report to the Phillies upon being traded to Philadelphia after the 1969 season. Flood received no support from his fellow players, who thought he was just trying to get a raise. When Flood testified at his hearing, no other current major league player attended the proceedings.

As much impact as the Staub-Clendenon trade had, perhaps the folksy wisdom of Luman Harris—manager of the Atlanta Braves in 1969 and a former Astros manager—summed up the Staub deal best. “Houston should lose Staub for even thinking about trading him,” Harris said. “Maybe that’s what Kuhn was thinking, too.”15

NORM KING lives in Ottawa, Ontario, and has been a SABR member since 2010. He has contributed to a number of SABR books, including “Thar’s Joy in Braveland: The 1957 Milwaukee Braves,” “Winning on the North Side: The 1929 Chicago Cubs,” and “A Pennant for the Twin Cities: The 1965 Minnesota Twins.” He thought he was crazy to miss his beloved Expos after all these years until he met people from Brooklyn.

Additional Sources

The Atlantic

Gordon, Robert. Then Bowa Said to Schmidt. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2013

Florence Times-Tri-Cities Daily (Florence, Alabama)

Hardball Times

Indiana Gazette (Indiana, Pennsylvania)

Montreal Gazette

SABR biography of Donn Clendenon, by Ed Hoyt

Vernon Daily Record (Vernon, Texas)

Notes

1. Video: “Les Expos, Nos Amours,” Volume 1, Labatt Productions, 1969.

2. Mark Mulvoy, “In Montreal they love Le Grand Orange,” Sports Illustrated, July 6, 1970

3. “Staub Says Astro Club Asked Him To Take Big Cut,” El Paso Herald-Post, January 24, 1969.

4. Mulvoy.

5. Emil Tagliabue, “Staub Mystery,” Corpus Christie Caller Times, January 26, 1969.

6. He was known as “The Hat” because he continually played around with his baseball cap when he was in the batter’s box.

7. Jimmy Wynn with Bill McCurdy, Toy Cannon: The Autobiography of Baseball’s Jimmy Wynn (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010), 106.

8. Michael Beschloss, “How Sandy Koufax’s Motel Helped Lead to Baseball’s Big-Money Era,” The New York Times, May 30, 2014.

9. Jonah Keri, Up, Up, & Away: The Kid, The Hawk, Rock, Vladi, Pedro, Le Grand Orange, Youppi, The Crazy Business of Baseball, & the Ill-fated but Unforgettable Montreal Expos (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014).

10. John Wilson, “Jesus Alou Already Astro Gem,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1969.

11. “Angry Staub Threatens To Quit If Deal’s Voided,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1969.

12. Wilson, “Hofheinz Blasts Kuhn, Sues Over Staub Deal,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1969.

13. Wynn, McCurdy.

14. Wilson.

15. Mulvoy.