The Quebec Adventures of Chappie Johnson’s All Stars

This article was written by Christian Trudeau

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

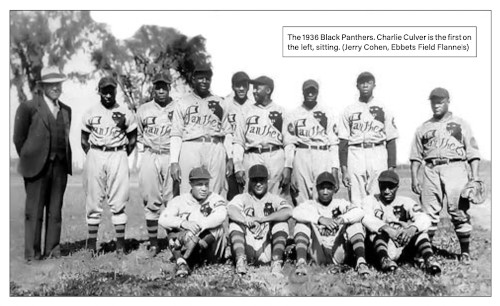

The 1936 Black Panthers. Charlie Culver is the first on the left, sitting. (Jerry Cohen, Ebbets Field Flannels)

The reception that Jackie Robinson received in Montréal is well known. A few years later, the Provincial League became a prime destination for Negro League veterans. Many factors can explain how that came to be, but a neglected factor is the presence, almost a generation earlier, of Chappie Johnson and his African American team. For a decade starting in 1927 he held an almost constant presence in Quebec.

For more than four years, Johnson based his team in the province, before supplying players to different teams. He brought in tremendous athletes, playing everywhere in Southern Quebec. While his team remained 100 percent African American, some of his players integrated local teams. A few incidents occurred over the years, but the experience was largely positive: Their name was synonymous with victory, and 15 years after their departure there were still signs of their presence in the Quebec vocabulary.

After briefly describing the baseball scene when Chappie first set foot in Quebec, this article will describe his adventures in Quebec, before listing the players stolen from Chappie by local teams, and concluding with the cultural impact of his presence.

CHAPPIE JOHNSON BEFORE 1925

Born in 1877 in Ohio, George “Chappie” Johnson had a two-decade career as a player for various African American teams, building a reputation as an excellent defensive catcher. He notably played with Rube Foster, Sol White, Pete Hill, Joe Williams, and Pop Lloyd, all inducted into Cooperstown. Already in his 40s when the Negro Leagues were born, Chappie moved to inferior circuits, where he acted as manager and team owner. His first mention in Quebec newspapers came in 1925, when he managed a team sporting his name, the Chappies, based in Schenectady, New York. They visited Sherbrooke for a three-game series.1 They won 12-2 and 8-2 against the local team, with the third game rained out.2 Newspapers did not hesitate to claim that this was the best team ever seen in town, at least as good as the Boston Braves,3 who had been seen twice previously in the Eastern Townships capital, in 1920 and 1923.4

QUEBEC BASEBALL IN THE 1920S

With the Royals having left Montréal after the 1917 season, the province had no pro team for part of the decade. The Eastern Canada League (1922-23) and the Quebec-Ontario-Vermont League (1924), both Class-B circuits, provided Quebec good baseball, but 1925 saw only strong semipro leagues in Montréal, and some good independent clubs elsewhere in the province, but little formal structure.

The province saw a first wave of visiting African American teams at the end of the 1910s. They were quite popular, returning year after year and attracting large crowds. The Manhattan Giants even spent the 1920 season in the province, renaming themselves the Quebec Royals for the occasion.5 A few players, like Charlie Culver and Chick Bowden, even decided to move permanently to Quebec, with Culver bending the color line by playing six games in the 1922 Eastern Canada League.6 The province was thus well aware of African American baseball, and Chappie Johnson was about to push that relationship up a few notches.

1927 : RESCUING THE MONTRÉAL CITY LEAGUE

The beginning of July 1927 provided the first news that Chappie Johnson was coming to Montréal: He published an ad challenging the best teams in the province, listing a St. Antoine Street address to contact him.7

His timing could not have been better. In 1927 two semipro leagues were battling for attention in Montréal: the City League, older and better established, and the more recent Guybourg League. Two leagues may have been too many for the city, and the St. Henri team of the City League was out of funds. League officials turned to Chappie to fill the vacant spot. Chappie was confident, even though he inherited St. Henri’s 3-6 record; he even boasted that attendance would double in a month.8

Everything was in place for a success. The show started even before the first pitch, as the Chappies brought shadowball to Quebec, a common element of the show offered by African American teams consisting of players pretending to hit, field, and throw an invisible ball. On the field, the team was impressive, catcher Duke Lattimore and shortstop Babe Hobson attracting the most attention. Both had short Negro Leagues careers, content instead to stay with Chappie. The team did feature some players with more impressive resumes, although they received less publicity, notably second baseman Frank Forbes, a veteran of good teams of the 1910s, and pitcher Wayne Carr, who alternated between the Chappies and the Eastern Colored League. Chappie seemed to have a close relationship with the Brooklyn Royal Giants in that league, bringing in outfielder Country Brown toward the end of the season. Agustin Parpetty, veteran Cuban hitter at the tail end of his career, was also brought in as reinforcement. Parpetty was inducted into the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.9 Chappie also had a few interesting prospects, notably Ted Page, who became the regular right fielder on one of the best teams ever, the 1933-34 Pittsburgh Crawfords, with Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, and Satchel Paige as teammates. Another youngster on the Chappies was Dick Seay, a superb defensive second baseman who, a decade later, was part of the Newark Eagles’ Million Dollar Infield, next to three players who ended up in Cooperstown: Mule Suttles, Willie Wells, and Ray Dandridge.10

All these reinforcements were needed, as the Ahuntsic club proved a tough opponent. Led by Culver, Bowden, and pitcher Rusty Yarnall, who had pitched an inning for the Philadelphia Phillies the previous season, the Ahuntsic team managed to take a few games from the Chappies. This rivalry quickly attracted the large crowds predicted by Chappie, overshadowing the Guybourg League as well as other members of the City League. The two teams met in the finals, splitting the first two games. The deciding game was tied, 3-3, in the ninth inning when Ahuntsic scored four times to win the championship.11

A strange episode occurred when the Philadelphia Giants, coming through Montréal, challenged the Chappies for what they dubbed the World Black Championship. The Chappies refused to meet them; it remains unclear whether the teams were unable to agree on profit-sharing or if Chappie thought he had too much to lose from such a challenge.12

The season was a success, on the field and in the ledger book. The team’s return for 1928 was announced, and both Chappie and star shortstop Babe Hobson even spent the winter in Montréal.13

1928 : TOO BIG FOR THE CITY LEAGUE

The Montréal baseball scene changed a lot in a year: The Royals were back in the International League in a brand-new Delorimier Stadium in 1928, and the Guybourg League had disbanded. The Chappies, back in town after a monthlong spring training in the US south, were ready for another season in the City League, with pretty much the same roster as in 1927.14

Still riding the wave of the interest generated by their rivalry, the Chappies and Ahuntsic announced a seven-game series across the south of the province.15 Even if it were to obtain permission to use Delorimier Stadium on Sundays when the Royals were on the road, the City League suffered from its top two teams preferring these outside activities. The relationship between the league and the Chappies worsened as the Chappies realized how valuable they were. In early July, the City League, no longer willing and able to accept the team’s financial demands, kicked the Chappies out.16 They then had a 4-1 record. The league soon imploded, with Ahuntsic the only team strong enough to continue operating.

Freed of their league obligations, the Chappies played seemingly everywhere, and against whoever promised a nice paycheck. On August 4 they defeated the Brooklyn Royal Giants and their ace pitcher Dick “Cannonball” Redding by a score of 5-4 in front of 4,000 spectators at Delorimier Stadium.17 A week later, they played the City League’s Beaurivage team in the first game of a doubleheader in which the headliners were the New York Giants, taking advantage of a break in their National League schedule to play against Ahuntsic.18 The Philadelphia Tigers, a barnstorming African American team, were their opponent in a September series.19

The Chappies concluded their season with a splash: On October 14 they faced off against an Ahuntsic club reinforced for the occasion by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. The two Yankees were coming through Montréal as part of a North American tour. While it had been announced that the two stars, just off their World Series triumph, would play against one another, they both ended up with Ahuntsic. The Chappies still fought ferociously, as it took a Gehrig home run in the ninth inning for them to lose, 8-6.20 Ruth pitched in relief of Charlie Culver, striking out three Chappies. However, The Babe was himself a victim of Chappies pitcher Lefty Dillard.

Chappie may have pushed his demands a bit too far on this occasion. According to newspapers, when he saw the huge crowd he asked for more money. Organizers reluctantly gave him an extra $200, while swearing never to deal with him again.21

Perhaps feeling that business would promise to be more difficult in Montréal from that point, Chappie announced that he would operate from Quebec City in 1929.22 He’d be in charge of a team in the newly founded Provincial League, which, like the Eastern Canada League seven years earlier, would have teams in Ottawa, Montréal, and Cap-de-la-Madeleine. But this time there would be no affiliation with Organized Baseball. Johnson himself headed to Trois-Rivières for the winter, as he had been recruited as manager of a bowling alley.23

1929: A PROMISING DEBUT

Chappie arrived in Quebec City in 1929 after promising to round out his team with five or six local players. This number was quickly reduced to two or three, then to zero. Chappie was apparently not against the use of local players, but as he was barnstorming regularly while fulfilling his league obligations, the attraction of his team was the presence of its African American players. Thus, local players would have been bad for business.

The rivalry with Ahuntsic was replaced by one with the Montréal team of the Provincial League, as the two teams pushed each other to excellence. The Montréalers obtained permission to use two (marginal) players of the Montréal Royals, William O’Hara and Ralph Brewer. The Chappies, who had lost their star catcher Duke Lattimore, saw more roster turnover than usual. Veteran Negro Leaguer John Cason replaced Lattimore behind the plate, but his power of attraction with fans was considerably less than that of his predecessor. The new league featured the most complete statistics of the era, revealing that newcomers Johnson Hill (.419 with two home runs in 13 games) and Cleo Smith (.679 with seven doubles and two triples in seven games), two more Negro League veterans, provided solid support for Babe Hobson (.468 with 10 doubles, one triple, and one home run in 19 games). On the mound, the star pitcher was Ed Dudley, who had had a much briefer career in the Negro Leagues, but dominated with a 7-1 record in the Provincial League.24

Although the rivalry was good for Montréal and for the Chappies, the two other teams were struggling. The Ottawa franchise was transferred to Quebec City in early July.25 Thereafter known as Quebec-Lambert, they created a stir by signing Willie Gisentaner, famous Negro Leagues left-handed pitcher.26 But rain canceled the game in which he was scheduled to appear, and it seems he did not get another chance with the team. The Quebec-Lambert team, while improved, fell behind the league leaders, so with the Cap-de-la-Madeleine team having folded, the league moved in mid-August directly to a playoff series between the Chappies and Montréal. The Chappies, who went 15-4 in the regular season, prevailed. The rest of the season saw the Chappies alternate between exhibition games and challenges with Montréal.

Among the exhibition visitors were the Brooklyn Tigers, the House of David, and the Brooklyn Royal Giants. The best show, however, was provided by the Havana Red Sox and their pitcher Luis Tiant Sr. For one of the challenges, the Montréal team and its manager, Dave Major, hired one player from the House of David team and two from the Havana Red Sox, as well as Gisentaner as pitcher. The Chappies swept the doubleheader anyway.27 The only saving grace for the Montréalers was that they were able to beat the Havana Red Sox, to whom the Chappies lost three times.

At season’s end, Chappie surprised everybody by announcing that he would be switching allegiance; he signed as manager for the Quebec-Lambert team for 1930.28

1930: THE SHOW MUST GO ON

Chappie arrived in Quebec City in the spring of 1930 to work for his new boss, J.A.T. Lambert. Talks were ongoing for the return of the Provincial League, but they were moving very slowly. In early May, with nothing imminent, the Chappies announced that they would operate as an independent team in 1930.29 Once again, Chappie’s decision carried weight, and soon thereafter the league abandoned its project.

The result was a lackluster season. Chappie attracted quite a bit of publicity when he signed a tall left-handed pitcher, Nip Winters, among the best African American pitchers of the 1920s. Stats show a 54-17 record with Hilldale of the Eastern Colored League between 1924 and 1926, with a Negro World Series title in 1925. He also had a 3-0 record with a save in five appearances against major-league teams.30 Winters, who had played with Chappie before his successes, was having problems with the bottle that were derailing his career. While he was immediately recognized as one of the top pitchers in the province, it was a game in which he hit two home runs that was his most memorable one in Quebec.31

Chappie finally fulfilled his promise to add a local player to his team … in a way. The local player was Charlie Culver, the former Negro Leaguer who had been in Quebec for a decade.32

The Havana Red Sox returned, and this time the Chappies took two out of three games.33 It was the African American version of the House of David team that gave them trouble, sweeping the Chappies in late August. Locally, Montréal promoter Jos. Choquette built a team that served as the Chappies’ main rival for most of the season, replacing Ahuntsic, which did not survive the collapse of the Provincial League. The teams split a two-game series in September.34

The season concluded with the rumor that Chappie had agreed to manage a team in Minneapolis in 1931.35 For the first time in four years, the Chappies’ future was uncertain.

1931: THE END OF THE LINE

With the Minneapolis rumor proven untrue, the Chappies were back in Quebec City in the spring, returning with Napoléon Côté, the promoter with whom they had worked in 1929. The Québec-District League was established, with two local teams, Lévis, across the St. Lawrence River from Quebec City, and the Quebec City Canadiens, and two African American teams, the Chappies and the Mohawk Giants. The schedule called for 30 games per team, with games played at the Exposition Park.36

Early-season returns did not meet expectations, as crowds were disappointing. The Chappies, still led by Babe Hobson and Charlie Culver, lost their supporting cast and struggled on the field. They were swept by the Canadiens, and soon played second fiddle to the Mohawk Giants, led by popular catcher Duke Lattimore.

The Chappies left for one of their barnstorming trips in New England, and when they returned, they were kicked out of the league for having missed three league games.37 The Chappies had had successes before even with no league to play in, but that was with a successful team. In mid-June in Montréal, they were swept by the House of David.38 The Québec-District League disbanded in early July.39 The Chappies, too, disappeared; they left the province, about four years to the day after having set foot in Montréal in 1927.

A BRIEF RETURN IN 1935

Out of the province from 1932 to 1934, the Chappies resurfaced in Quebec in 1935, after quite an evolution on the local baseball scene. A new Provincial League with eight clubs had been established, with teams in Montréal (two), Lachine, Sherbrooke (two), Sorel, Granby, and Drummondville. However, by midseason there was financial trouble, the schedule was suspended, and an invitation was issued to any barnstorming team to visit to face the Provincial League teams. This is how the Chappies returned, to Granby for a game on July 24. Other visitors included the Zulu Cannibal Giants, Japanese All Stars, Cleveland Clowns, and House of David, but the Chappies’ particular calling card was nostalgia. Newspapers did not miss the chance to remind their readers of the Chappies’ past in the province. It was also revealed that the team was now part of a league in upstate New York, playing against teams from Ogdensburg, Saranac Lake, Watertown, and Carleton. A few players from the Quebec days were still with the team, including Babe Hobson, now behind the plate, and Charlie Culver, who had left Quebec temporarily to follow Chappie.40 While they shut out Granby in their first game back,41 the Chappies struggled overall, losing to Sorel, Lachine, and the Montréal Police team (also part of the Provincial League). They concluded their exhibition tour with a loss at Delorimier Stadium against an old rival, Jos. Choquette.42

With the finances back under control, the league resumed its activities, and the Chappies left the province again, most likely to finish their season in upstate New York.

THE BLACK PANTHERS

The Provincial League continued its activities in 1936, adding an African American team, the Black Panthers. While Chappie Johnson was not, as far as the author knows, directly linked to the team, it seems likely, as claimed by Merritt Clifton,43 that he sent many players to the team. Owned by Jack Wilson of Montréal and Jock Smith of Chicago, the team featured a number of former Chappies, including Charlie Culver as manager. Others were outfielder Ted Waters, who had been with the Chappies intermittently since 1929, and Ernie “Black Bear” Jackson, a light-hitting first baseman known for his fantastic glove, and a Chappie regular since 1927. Famous pitcher Nip Winters, now truly at the end of his career, also returned briefly to Quebec with the Black Panthers.44 While it’s possible that Chappies veterans volunteered to come back to Quebec, it’s more likely that Chappie himself had a word in the roster composition.

The Black Panthers were in the middle of the pack in 1936, before collapsing in the round-robin tournament that served as the league playoffs. The 1937 edition of the team employed mostly youngsters, as veterans from the Chappies era were almost nonexistent. They slid to the bottom of the standings in a quickly improving Provincial League, finishing with a 10-50 record.45 They did not return in 1938. It was the end of an era, the last time a team linked to Chappie Johnson was present in Quebec.

PLAYERS HIRED AWAY FROM CHAPPIE

As soon as he arrived in Quebec, Chappie Johnson had to deal with the possibility that his players would be recruited by local teams. It was a phenomenon with some history, as before Chappie, Charlie Culver, Chick Bowden, Peerless Green, and others had stayed behind after touring in Quebec.

The first mention of such hirings was in the spring of 1928. St. Hyacinthe, a team always looking for the best available players, signed pitcher Wayne Carr and catcher Harry Creek.46 When the Chappies were kicked out of the City League later that season, six of their players moved temporarily to St. Hyacinthe.47 The situation was likely encouraged by Chappie, as it prevented his players from leaving the province while he arranged exhibition games that allowed him to pay their salaries.

In 1930 Bedford invested in a strong team to compete in a league with Farnham, Iberville, and Sherbrooke. They hired Ed Dudley, star pitcher of the 1929 Chappies.48 Their Farnham rivals announced that they had signed star shortstop Babe Hobson,49 but he only showed up in October.50 Toward the end of the season, the Québec Canadiens, who battled the Chappies in 1930 and 1931, hired Nestor Lambertus, a Cuban outfielder who had been with the Havana Red Sox but had also played briefly for the Chappies.51 The next year the Canadiens hired pitcher Spitball Smith from the Mohawk Giants.52

In 1935, during the team’s brief stay for the Quebec exhibition tour, Chappie loaned Fred “Evil” Wilson to Granby, integrating the Provincial League. Wilson, a gifted but temperamental player, would in the following years spend time in both jail and the Negro Leagues, before coming back to the province with the Verdonnet, a Quebec City team, in 1945. In 1936, after the Black Panthers had been eliminated, Granby picked up Ormand Sampson, a transaction eventually ruled illegal by the league because it had occurred during the playoffs.53

A few Black Panthers extended their stay in the province, notably pitcher Al Flemming, who played for various teams up to at least 1952, when he served as player-manager with Lachute.54

THE CULTURAL IMPACT OF THE CHAPPIES

The Chappies were in the eyes of the Quebec media for more than four years, and left a mark. Of course, given the era, derogatory terms55 are often used to describe them. But it was primarily their talent that impressed. Soon a few juvenile teams called themselves the young Chappies. Even the senior hockey team in Thetford Mines took the name for the 1929-30 season. In 1931 a young first baseman, excellent defensively, was said to play “like Jackson from the Chappies,” a reference to Ernie “Black Bear” Jackson, a mainstay at first base for the Chappies.56

A tribute that does not age well occurred in Lévis in 1931. After a religious celebration young parishioners divided themselves into two groups, the Chappies and the Nationals (for the local team in the Québec-District League). To emphasize the distinction between the two teams, the Chappies played in blackface. In 1933 a similar practice was observed in Pike River, with the second group this time using fake beards to personify the House of David.57

Periodically, news brought back memories of the Chappies, even years after their departure. When the United States Negro Leagues played multiple games in Quebec in 1945, many comparisons to the Chappies were made. For instance, in Le Canada: “In Montréal, we’ve always liked seeing black baseball players in action. We still recall the Chappie Johnsons, in particular catcher Lattimore who was marvelling the crowds with his play behind the plate and his bat. If blacks had been admitted in organized baseball, Lattimore would not have been in Montréal for long. That was one, for sure, that was of major league caliber.”58

In 1951, with the Provincial League now a Class-C league, Sam Bankhead, in charge of the Farnham Pirates, became the first African American manager in Organized Baseball. His team was composed primarily of African American players, leading some newspapers, chief among them Le Nouvelliste de Trois-Rivières, to refer to them as the Chappies.59

Chappie Johnson died on August 17, 1949, in South Carolina. At least one Quebec newspaper, Le Nouvelliste de Trois-Rivières, mentioned his death in the weeks following, recalling the winter he had spent in the town as manager of a bowling alley.60

Author John Craig, from Peterborough, Ontario, in 1979 published Chappie and Me, a semi-autobiographical novel about a young White player joining the barnstorming Chappies for a few months in 1939, playing in blackface. While the book must not be taken as historically accurate, the Chappies are described as a purely barnstorming team traveling with a portable lighting system, something they never had during their stay in Quebec. The Chappies from the novel tour the US and Canada in the summer before retreating to the Caribbean for the winter. Craig also recalls the Chappies’ traveling to the protagonist’s town (presumably Peterborough) every summer, something that could have happened from their base in Quebec or upstate New York. The novel contains a brief mention of Quebec, as the protagonist and a few teammates meet a French-Canadian cook at an Illinois fair. The cook recalls having seen them play in Trois-Rivières, a fun coincidence (or not) given the history Chappie had with the city.61

The book and later the musical inspired by the novel were mentioned in Quebec media in the 1980s, but without anybody recalling the time Chappie actually spent in the province.

CONCLUSION

It is impossible to know what Chappie Johnson was thinking when he showed up in Quebec. Was it a welcoming land, a nice business opportunity, or a bit of both? In the end, he contributed greatly to the image and reputation of African American baseball in Quebec by offering great exhibitions across the south of the province. As some of his players played in the Negro Leagues, and could have played in the majors, Chappie offered to many of these towns a very high level of baseball, possibly the best ever seen in their town.

The media of Jackie Robinson’s era made no connection between Robinson and Chappie Johnson. But there’s little doubt that the constant media presence of the Chappies over five summers normalized African American baseball in Quebec. His presence also forced his rivals to innovate to keep up with him, including pushing to integrate. Chappie’s role with the Black Panthers is less clear, but that team played a crucial role in the rise of the Provincial League, helping them generate revenues and gain credibility.

Maybe Quebec was only an unexploited land in which Chappie could make an easy buck, without competition. But even if that wasn’t his goal, he ended up being a trailblazer.

CHRISTIAN TRUDEAU is a professor of economics at the University of Windsor. For the last 20 years, he has researched Quebec baseball history. His findings are documented at LesFantomesduStade.ca.

Acknowledgments

Gary Fink provided helpful comments on an early draft. Merritt Clifton’s research on the Provincial League touched on Chappie Johnson’s stay in Quebec, and a conversation with him clarified some details.

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com and Seamheads.com were the main references. Many Quebec newspapers were consulted (available on the website of the Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec).

Notes

1 They came to Sherbrooke as the local team was in financial turmoil. “Players may carry on with baseball here,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, July 13, 1925: 8.

2 “Statement of Baseball Club; Locals Lost,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, July 15, 1925: 9; “Schenectady Team Scored Over Locals,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, July 16, 1925: 9.

3 “Le Sherbrooke a Encore été Défait,” La Tribune de Sherbrooke, July 16, 1925: 6.

4 The Braves won 21-2 in 1920 and 2-1 in 1923: “Large Crowd Present to See Braves,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, October 11, 1920: 4; “Boston Braves Won Battle in Ninth Inning,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, October 8, 1923: 8.

5 “Victoire de l’Athlétique,” La Presse, May 14, 1920: 6.

6 Christian Trudeau, “24 Years Before Jackie Robinson, Charlie Culver Broke Barriers in Montréal,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2020.

7 “Un Club de Nègres Jouera Ici,” Le Canada, July 6, 1927: 2. The address is of a convenience store owned by William Henry Parham, a member of the local African American community. See 1927-28 Lovell’s Montréal directory.

8 “Nouveau Club dans la Ligue de la Cité,” La Presse, July 8, 1927:20.

9 Player lists are obtained from box scores and accounts in Montréal newspapers. Player backgrounds are from Seamheads.

10 Both Page and Seay credit Chappie Johnson for their successful careers, helping them to transition from raw athletes to polished players. See John Holway, Black Giants (Xlibris Corporation, 2009).

11 “L’Ahuntsic Est Champion de la Ligue de la Cité,” La Presse, October 17, 1927: 20.

12 “Les Giants de Philadephie à Guybourg,” La Presse, September 29, 1927: 24.

13 “Glanures Sportives,” L’Autorité, October 16, 1927: 4.

14 “Doc Newton Jouera avec le St-Laurent,” La Presse, March 16, 1928: 23.

15 “L’Ahuntsic et les Chappies à Iberville,” La Presse, May 23, 1928:25.

16 “Le Club de Baseball de la Brasserie Frontenac Remplacera les Chappies dans la Ligue de la Cité,” La Presse, July 5, 1928: 20.

17 “Deux Belles Exhibitions Hier, au Stade,” La Presse, August 5, 1928:16.

18 “Les Giants Déclassent l’Ahuntsic,” La Presse, August 12, 1928:18.

19 “Quatre Victoires pour les Chappies,” La Presse, September 10, 1928: 18.

20 More precisely, Ahuntsic was the away team, and Gehrig’s home run was at the top of the ninth inning. But the field was then filled with seat cushions from the overexcited crowd. Given the cold weather, the game was not resumed. See “Belle Exhibition de Ruth et Gehrig, Hier au Stade,” La Presse, October 15, 1928: 10.

21 “20,000 Personnes Acclament Ruth et Gehrig,” La Patrie, October 15, 1928: 10.

22 “Organisation de la Ligue Provinciale,” La Presse, October 17, 1928: 20.

23 “Chappie Johnson Gérant de la Salle de Quilles Loranger,” Le Nouvelliste, October 20, 1928: 6.

24 Stats were published at the end of the season: “Un Bon Debut pour la Ligue Provinciale,” Le Canada, October 2, 1929: 2.

25 “Nap Côté et un 2e Club à Québec,” Le Soleil, July 11, 1929:16.

26 “Disentaener [sic] et Silver avec le Club Lambert Dimanche,” Le Soleil, July 31, 1929: 14.

27 “Le Québec Chappie Enlève avec Brio Ses Deux Parties d’Hier Contre Montréal, ” Le Soleil, August 26, 1929: 15.

28 “Chappie Johnson avec le Club de J.A.T. Lambert l’An Prochain,” Le Soleil, October 24, 1929: 17.

29 “De Forts Clubs Viendront Jouer Contre l’Équipe de J.-A.-T. Lambert,” Le Soleil, May 6, 1930 : 16.

30 Seamheads.com.

31 “Les Chappies Remportent une Double Victoire Sur Les Cuban Stars Hier au Parc de l’Expos,” Le Soleil, June 9, 1930:13.

32 “Les Chappies à Montréal,” Le Soleil, September 12, 1930:16.

33 “Les Havana Red Sox et les Chappies Partagent un Double Header Hier,” Le Soleil, August 4, 1930: 12.

34 The Choquette team featured three players from the Montréal Canadiens: Wildor Larochelle, Armand Mondou, and future Hockey Hall of Famer Aurèle Joliat. “Les Chappies à Montréal,” Le Soleil, September 12, 1930: 16.

35 “Chappie Johnson Demeurera aux États-Unis en 1931, à en Croire la Rumeur,” La Tribune, December 15, 1930: 6.

36 “Chappies et Canadiens Inaugureront la Saison au Parc de l’Exposition,” Le Soleil, May 8, 1931: 19.

37 “Les Chappies ont Maintenant Fini Leur Règne à Québec,” Le Soleil, June 9, 1931: 15.

38 “Deux Victoires pour la Maison de David,” La Presse, June 22, 1931: 19.

39 “La Ligue Que.-District Suspend Ses Activités,” Le Soleil, July 3, 1931:14.

40 “Choquette Reçoit les Chappies au Stade, Dimanche,” La Presse, August 24, 1935: 34.

41 “Granby shut out by Chappie Johnsons,” Granby Leader-Mail, July 2 5 , 1935: 8.

42 “Chappies Battus 5-4 par Jos Choquette,” Le Canada, August 26, 1935: 11.

43 Merritt Clifton, “Quebec Loop Broke Color Line in 1935,” Baseball Research Journal, 1984.

44 “Alignements des Panthères Noires et du Club Granby,” L’Illustration Nouvelle, May 1, 1936: 17.

45 Christian Trudeau, “Integration in Quebec: More Than Jackie,” Jane Finnan Dorward, ed., Dominionball: Baseball above the 49th (Cleveland: SABR, 2005), 85-89.

46 “Deux Joueurs des Chappies avec le Club St.-Hyacinthe,” La Presse, April 25, 1928: 26.

47 “St. Roch and Magog meet here this evening,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, July 11, 1928: 7.

48 “Le Club Bedford Aspire au Titre de Champions,” La Presse, April 2 4 , 1930: 27.

49 “Babe Hobson pour Farnham,” La Tribune, April 28, 1930: 6.

50 “Le Farnham se Signale,” Le Canada, October 3, 1930: 3.

51 “En Peu de Mots,” Le Soleil, August 9, 1930: 7.

52 “Joutes de la Ligue Québec-District Hier et Dimanche – Smith Reste avec le Canadien,” Le Soleil, May 15, 1931: 21.

53 Merritt Clifton, “Quebec Loop Broke Color Line in 1935,” Baseball Research Journal, 1984.

54 “Lachute Inaugure le Système d’Éclairage de Son Stadium,” Le Canada, July 7, 1951: 8.

55 We often find the French translation of “Negro,” which sits somewhere in between Negro and the N-word in terms of connotation.

56 “Derby Line Vt Can. Celanese,” Le Soleil, June 12, 1931: 16.

57 “Pike-River,” Le Canada-Français, August 31, 1933: 4.

58 “Brown Bombers et les Crawfords au Stade Dimanche,” Le Canada, July 11, 1945: 8.

59 “Les Royaux: Québec à Nouveau Ce Soir et les ‘Chappies’ de Farnham Dimanche,” Le Nouvelliste, June 2, 1951:11.

60 “Chappie Johnson Décédé à 79 Ans,” Le Nouvelliste, August 31, 1949: 9.

61 John Craig, Chappie and Me (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1979).