The Remaking of Casey Stengel

This article was written by Marty Appel

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

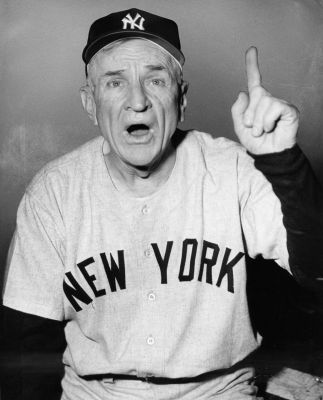

Until the Dodgers and Giants come to their senses and return home to New York, Casey Stengel remains the only figure in history to have worn the uniform of these four New York City teams: the Dodgers, Giants, Yankees, and Mets. The coincidence of this was no small thing to Casey, who died in 1975, but who was aware of the distinction and was occasionally introduced that way at Old Timers gatherings he attended. During his playing days he earned a reputation as one of baseball’s clown princes. Who could have predicted that during a long tenure as skipper of the Yankees he would build a reputation as a managerial genius? He could have rested on those laurels all the way into the Hall of Fame, but when the chance to manage the expansion Mets came along, Casey risked his hard won reputation in a return to clown prince status.

Until the Dodgers and Giants come to their senses and return home to New York, Casey Stengel remains the only figure in history to have worn the uniform of these four New York City teams: the Dodgers, Giants, Yankees, and Mets. The coincidence of this was no small thing to Casey, who died in 1975, but who was aware of the distinction and was occasionally introduced that way at Old Timers gatherings he attended. During his playing days he earned a reputation as one of baseball’s clown princes. Who could have predicted that during a long tenure as skipper of the Yankees he would build a reputation as a managerial genius? He could have rested on those laurels all the way into the Hall of Fame, but when the chance to manage the expansion Mets came along, Casey risked his hard won reputation in a return to clown prince status.

The scope of his career includes six different decades, spanning such a long period that he went from the days of John McGraw to the days of Tug McGraw. He chased down fly balls hit by Babe Ruth and platooned Ron Swoboda in left field. He played for the Brooklyn Superbas (later Robins) 1912–17 and the New York Giants 1921–23. He coached for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1932–33, and managed them 1934–36. He managed the Yankees 1949–1960 and then the Mets 1962–65.

Thirty years of New York baseball in his 54-year career. He batted against Christy Mathewson and sent Cleon Jones up to pinch-hit. When Sandy Koufax no-hit his Mets in 1962, he was asked after the game if Koufax might be the “best he’d ever seen.”

“Oh no,” he replied without pausing, “that would be Grover Cleveland Alexander.”

Casey’s path to the majors was relatively swift. He began with the Kankakee Lunatics in 1910. Yes, the Lunatics. Technically they were called the Kankakee Kays, but as their ballpark was located next to an asylum for the insane, the newspapers couldn’t resist. So Casey started off as a Lunatic and went from there.

The next year “Dutch” (not yet Casey) was playing for Aurora, Illinois, which by good fortune was a short and direct train connection to Chicago. Brooklyn scout Larry Sutton took a train and watched Stengel play a few games.

“I was always partial to boys with blonde hair and blue eyes,” said Sutton. “That combination is always a fighter.”

Thanks to the easy train ride, and Stengel enjoying a few good days, he got a Brooklyn contract, and by September 1912 was in the big leagues.

He arrived by train at Penn Station, and took a small hotel room in Times Square. It was his first day ever in New York City, and it would take him several hours by public transportation to find his way to Washington Park in Brooklyn, where he hung his clothes on a nail and shyly introduced himself around.

His teammates (hardly “illustrious”), generally ignored him, as was the fashion with rookies. It even took several days for them let him take batting practice, and to recommend an apartment in Brooklyn (The Fulton Arms near Borough Hall) where some of them lived.

In his very first game, the left-hand hitting prodigy went 4-for-4 and then had the audacity to switch to the right side of the plate for his fifth plate appearance (he walked). He had never been a switch-hitter, and here he was pulling off this stunt in his debut game. The 4-for-4 with two RBIs and three stolen bases remains one of the best debut games in major league history.

He wound up playing in the final game in Washington Park, and the first game in Ebbets Field, hitting the first home run in Ebbets Field.

Casey’s time with the Dodgers was very much defined by his relationship with the team’s high-profile manager, Wilbert Robinson. Casey was never sure if “Uncle Robbie” liked him or not. He thought Robinson was a lot of fun to play for and Casey’s .316 season in 1914 seemed to make him an elite player, but the following year, nursing a shoulder injury, he plunged to .237, one of the lowest batting averages in the league. It did not help his standing when, during spring training of 1915 (the .237 season), he participated in a stunt in which Uncle Robbie was to catch a baseball dropped from an airplane flying over the practice field in Daytona Beach. It turned out it wasn’t a baseball, but a grapefruit, which exploded on Robbie’s chest, causing him to yell “I’m killed! I’m killed!”

Many blamed Stengel for the stunt gone bad, because by 1915, it seemed like a Stengel thing to do. (He may have been an instigator but was likely not on the plane himself.)

“When you are younger you get blamed for crimes you never committed,” he said. “And when you’re older you begin to get credit for virtues you never possessed. It evens itself out.” If we take him at his word, Casey’s later managerial prowess could have been a canny case of letting the press draw their own conclusions from his team’s success. But if Casey was a clown, he was a class clown in the school of baseball, learning from every manager he played for and often excelling on the field. Had there been All-Star Games in those days, he would likely have been chosen for two or three.

In 1916, Brooklyn won its first pennant of the twentieth century, losing to Babe Ruth’s Red Sox in the World Series. Casey went 4-for-11 (.364) in the Series. In 1917, his final season with Brooklyn, he mastered the right field wall at Ebbets Field, recording 30 outfield assists, a total bettered only five times since. Up until the arrival of the “Boys of Summer” in the late 1940s, Casey would have been in the conversation of notable outfielders in franchise history. He was certainly a fan favorite, a matter enhanced when he made his return to Ebbets Field after being traded to the Pirates and famously doffed his cap to the crowd, releasing a stunned sparrow he had retrieved in the bullpen between innings. The “giving the fans the bird” incident came to exemplify his zany and colorful persona.

His “time” served in Pittsburgh included World War I military service—back at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where he got his first real taste of managing. He managed the shipyard team against incoming sailors from other ships. “Play ’em the first day they’ve landed,” he strategized, “before they get over their sea legs.” It wasn’t Casey’s first time in a managerial role, however. A fact rarely mentioned in his career recaps his stint as an assistant manager for the Ole Miss baseball team through a Kansas City connection.

Casey hated playing in Pittsburgh and was even more miserable when they traded him to the Phillies in August 1919. He refused to report, went home, and organized a barnstorming tour. If there had been a commissioner of baseball, this probably would have gotten him kicked out of Organized Baseball. He finally reported in 1920, and was lying on the training table in July 1921 when he was told he’d been traded to the New York Giants. He bolted from the table, ran onto the field, and celebrated by running the bases, sliding into each one. So much for whatever injury had him on the training table. He was going back to New York!

New York was truly the center of the baseball universe. Often four of the sixteen teams were in New York, some days as many as six, and all would socialize in the evenings at select watering holes in Manhattan. Casey, extroverted as he was, came to know everyone in the game.

Happy as he was to be returning to the city he had come to love, it was going to be a very different experience for him. Playing for John McGraw was not like playing for the jolly Uncle Robbie, where rules seemed meant to be broken. McGraw was strict, but Casey also learned a lot about the game under his tutelage. Just sitting in the dugout, listening to McGraw grumble about some botched play was an education. He marveled at how much McGraw knew.

But McGraw saw him mostly as a wiseguy and told him so.

Because of his now advancing age, and the Giants being laden with star players, Casey didn’t play as often as he would have liked. Although he’d often been swapped with Joe Riggert and Hy Myers against left-handers in his Robins days, being a part-time player now was his role. Casey would eventually become famous as a master of platoons as a manager himself. McGraw saw the managerial potential in Casey, often letting him coach first base and making him a frequent guest at the McGraw home for late night strategy sessions. One spring McGraw assigned him to coach sort of a “B squad” that trained 200 miles away from the San Antonio “big league” camp. Casey wasn’t ready to quit playing for coaching and he let McGraw know he resented it. He “fired” himself and returned to the big camp.

“That’s another smart-aleck thing you’ve done,” said McGraw.

Yes, the kid from Kansas City, who used to throw snowballs at men with pipes in an effort to dislodge them, was still a rascal.

Despite not playing every day, Casey was part of Giants championship clubs of 1921, 1922, and 1923. In the 1923 World Series—the first played in Yankee Stadium—he hit an inside-the-park home run to win the first game, and hit one into the right field bleachers to win game three, with a risqué thumb of his nose at the fans as he circled the bases. (Yankees owner Colonel Ruppert wanted him reprimanded; Judge Landis demurred).

Casey’s lifetime World Series batting average for 12 games was .393.

And then he was done.

After those Series heroics, McGraw traded him to the hapless Boston Braves.1 His playing career was nearly over, his professional managing career about to begin—first at Worcester (1925) and then at Toledo (1926–31), until the Depression left the team—and the Stengels—broke.

He leaped at an offer to become a Brooklyn Dodgers coach in 1932–33, and then succeeded Max Carey as the club’s manager in 1934. This was a low-budget team going nowhere, and after three second-division seasons, he was fired and paid not to manage in 1937. It was his only year out of uniform between 1910 and 1960. And all he did in that year off was invest in a Texas oil field that made him a rich man.2

Signed to manage the Boston Bees in 1938, Casey stayed for six lackluster years with four seventh place finishes. His final year, 1943, began with his being run over by a car in Kenmore Square before opening day and missing almost three months of work.

He followed that with five more seasons of minor league managing, including the Yankees farm club in hometown Kansas City in 1945. At Oakland, 1946–48, he managed a colorful group of veterans (and a very young Billy Martin), and won the Pacific Coast League championship in 1948 as the Yankees were disposing of their manager, Bucky Harris.

In a surprise hiring, the Yankees named him Harris’s successor, handing him the most coveted managing position in the game (along with Harris’s number 37).

“They hired a clown,” screamed the multitudes, feeling him a most un-Yankee-like choice.3 His record as a manager was certainly lackluster to that point. But the screaming abated after he won the 1949 world championship (despite more than 70 team injuries), during which time he perfected his version of platooning (it helped to have a lot of talent on the bench and various injuries forced him to be creative to great effect) and Stengelese—his unique brand of doubletalk which would enable him to circle around a question until he felt he had avoided or answered it. The writers—“my writers” he called them—found it amusing. Casey had found a way to take his “clown prince” mantle and wear it to shrewd advantage.

The ’49 championship erased all doubts about his managing prowess. By the time he had rolled off a fifth straight world championship, not only was he no longer a “clown,” he was on his way to Cooperstown. Although the Joe McCarthy-era Yankees like Joe DiMaggio and Phil Rizzuto never quite warmed to him, his own players—notably Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, and Mickey Mantle—were carving out their own Hall of Fame careers under his leadership.

Casey rode championship after championship through the ’50s, losing only to oil partner Al Lopez’s 1954 Cleveland Indians, and Lopez’s 1959 Chicago White Sox. When the Yankees fired him after he lost a seven-game World Series to Pittsburgh in 1960 (“I’ll never make the mistake of being 70 again,” he said), the Baby Boomer generation had lost a father figure. But all things must pass. The Yankees felt Casey mismanaged the pitching rotation in the ’60 World Series, but they also did not want to lose manager-in-waiting Ralph Houk, who was being pursued by both Detroit and Boston.

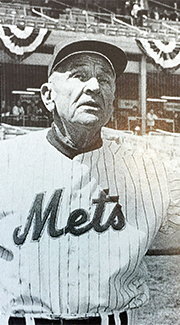

At that point in his career, Casey could have hung up his jersey for good. He would no doubt have been remembered as a colorful but astute mastermind of the game and a Hall of Fame shoo-in. But after sitting out 1961 in Glendale, largely to work on his autobiography, he allowed the expansion New York Mets to pluck him out of retirement and bring him back to New York. He and his wife Edna (neé Lawson) would continue to reside at the Essex House on Central Park South, as they had done throughout his Yankee years, even after the Mets moved to Shea Stadium in 1964 and the taxi fare to Flushing soared to six dollars! But first would come two seasons at the Polo Grounds, where he had played for the Giants, where he had met Edna, and where he had butted heads with McGraw.

At that point in his career, Casey could have hung up his jersey for good. He would no doubt have been remembered as a colorful but astute mastermind of the game and a Hall of Fame shoo-in. But after sitting out 1961 in Glendale, largely to work on his autobiography, he allowed the expansion New York Mets to pluck him out of retirement and bring him back to New York. He and his wife Edna (neé Lawson) would continue to reside at the Essex House on Central Park South, as they had done throughout his Yankee years, even after the Mets moved to Shea Stadium in 1964 and the taxi fare to Flushing soared to six dollars! But first would come two seasons at the Polo Grounds, where he had played for the Giants, where he had met Edna, and where he had butted heads with McGraw.

The Mets got a lot right immediately—the name, the announcers, the logo, the team song, the mascot, the uniform, the fans chanting “let’s go Mets,” and hiring a legend as manager.

But Casey was a different manager with the Mets. The year off from baseball and the realization that he was now in his 70s seemed to take a lot of the fire from his belly. Even late in his Yankee career, he was deeply engaged in the games, thinking three innings ahead, pushing the right buttons. With the Mets, he more or less turned over daily control to his coaches, Cookie Lavagetto and Solly Hemus, and let center fielder Richie Ashburn run things on the field. Casey (or the coaches), could still platoon, but now it involved sending in bad players to replace bad players. The Mets had done so many things right except build a talented roster. Realizing this, Casey’s best managerial move was to steer attention away from this horrible, 40–120 team, and onto the power of his personality. As it turned out, that was the winning move. The writers loved having him and admired his longevity and wit, and his ability to touch history.

While Casey became the face of the franchise, his coaches would work the pitching rotation, do the lineup, “suggest” pinch-hitters and defensive replacements. Roger Craig, his leading pitcher, was influential in evaluating pitching prospects, perhaps just as much as coaches Red Kress and Red Ruffing.

“Ain’t like the old days,” he whispered to Gene Woodling in the dugout one afternoon, winking. Woodling had been with the Yankees for the five straight; now, he was playing out his career with Casey at the Mets.

Yes, Casey might occasionally doze off in the dugout, but his old Yankee boss George Weiss (now the Mets president), and Joan Payson and M. Donald Grant (ownership) did not seem to mind. The team was considered an immediate hit, even though they averaged a mere 9,000 fans a game against the seven teams who were not the Dodgers and Giants. The illusion of success was strong, and Casey, once the “clown,” also proved to be an illusionist of sorts.

By the time the team moved to Shea in 1964, even some of his writers were thinking the Stengel era had run its course; it was time to shake up this now dull franchise. Even Casey was running out of jokes to distract from the bad play.

It ended for Casey in 1965 when he broke his hip in a fall that no one saw after an Old Timers party in mid-season. He was, at 75, the oldest man in uniform and one of the oldest managers in history. Hall of Fame induction would be speeded up to include him the following year, and he would spend the remaining ten years of his life living the good life in Glendale, but ever a presence on the baseball scene, whether in spring training, at banquets, in Cooperstown, or at Old Timers gatherings.

MARTY APPEL is the author of 24 books including “Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character,” published by Doubleday in 2017.

Select Bibliography

Allen, Maury. You Could Look it Up. New York: Times Books, 1979.

— Now Wait a Minute, Casey! Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1965

Appel, Marty. Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character. New York: Doubleday, 2017.

Bak, Richard. Casey Stengel: A Splendid Baseball Life. Dallas: Taylor, 1997.

Creamer, Robert. Stengel: His Life and Times. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984.

Durso, Joseph. Casey: The Life and Legend of Charles Dillon Stengel. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1967.

Goldman, Steven. Forging Genius: The Making of Casey Stengel. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2005.

Graham, Frank Jr., Casey Stengel: His Half-Century in Baseball. New York: John P. Day Co., 1958.

Howard, Arlene with Ralph Wimbish. Elston and Me: The Story of the First Black Yankee. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2001.

Koppett, Leonard. The New York Mets: The Whole Story. New York: Macmillan, 1970.

Stengel, Casey and Harry Paxton. Casey at the Bat. New York: Random House, 1962.

Stengel, Edna. Unpublished memoir, 1958.

Vecsey, George. Joy in Mudville. New York: McCall, 1970.

Notes

1 McGraw did bring Casey back in a Giants uniform for a European tour after the 1924 season, which doubled as a Stengel honeymoon.

2 A player, Randy Moore, whose father had invested in an oil well, got Casey and Al Lopez into a small group backing it, and the well came in. It made Casey a rich man for the rest of his life. That well is still pumping oil.

3 Forty-eight years later, “Clueless Joe” Torre, a longtime unsuccessful National League manager, received much the same greeting in New York.